Fallotaspidoidea

The ”Fallotaspidoidea” are a superfamily of trilobites, a group of extinct marine arthropods. It lived during the Lower Cambrian (Atdabanian)[3] and species occurred on all paleocontinents except for the Gondwana heartland (currently Latin America, most of Africa, Australia, Antarctica, India and China). A member of this group, Profallotaspis jakutensis, has long been the earliest known trilobite, but recently the redlichiid Lemdadella has been claimed as occurring even earlier.

| Fallotaspidoidea | |

|---|---|

| |

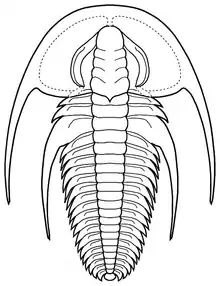

| Fallotaspis longa, drawing by Sam Gon III | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Superfamily: | ”Fallotaspidoidea”[1] Palmer & Repina, 1993[2] |

| Families | |

|

stem group genera:

| |

Distribution

”Fallotaspidoidea” occur in the Lower Cambrian of North America (Cordilleran region and northern Greenland), Europe (United Kingdom, Comley area; Ukraine), northwestern Africa and northern Asia (Siberia).[2]

Dispersion of the “Fallotaspidoidea”

Lieberman (2002)[1] suggests that fallotaspidoids, the first hard-shelled trilobites (or Eutrilobites), originate in the paleocontinent Siberia. The group quickly spread to southern Europe and northwestern Africa, which were part of the margin of Gondwana (or Peri-Gondwana), and northwestern Laurentia. The sutured Redlichiina developed from the fallotaspidoids somewhere in Siberia and the Gondwana-margin, and from there spread to all of Gondwana, including current China and Australia, where fallotaspidoids and other Olenellina were absent. In Laurentia the Fallotaspidoids were succeeded by Nevadioids, Judomioids and Olenelloids, the latter remaining the dominant group of trilobites until the extinction of all Olenellina at the very end of the Lower Cambrian, after which Redlichiina, Ptychopariida and Corynexochida took over.

Taxonomy

The views of scholars on the relationships of the taxa now assigned to the ”Fallotaspidoidea” have changed regularly over the past half century or so. Initially, the Olenellidae, which also encompassed the subfamily Fallotaspidinae, was regarded the sistergroup of the Daguinaspididae,[4] a view that made it into the Treatise of 1959.[5] Later, the genera now in the ”Fallotaspidoidea” were considered part of the Holmiinae, the sistergroup of the Olenellinae and the Nevadiinae.[6]

Bergström recognized within the family Daguinaspididae five subfamilies: the Daguinaspidinae and the Fallotaspidinae (including Andalusiana, and Bradyfallotaspis), together comprising the current ”Fallotaspidoidea”, in addition to the Nevadiinae, the Neltneriinae and the Callaviniinae.[7] This was followed by the view that the Archaeaspididae (including Bradyfallotaspis), the Fallotaspididae and the Daguinaspididae were all families of their own and sistergroups of the Olenellidae, Homiidae, and Nevadiidae.[8] Ahlberg et al., moved the Archaeaspis-group as a subfamily to the Callaviidae, leaving the Fallotaspis-group and the Daguinaspis-group as subfamilies in the Daguinaspididae.[9] Palmer and Repina erected two superfamilies, the Olenelloidea and the Fallotaspidoidea, the latter consisting of the Fallotaspididae (comprising the Fallotaspidinae and the Daguinaspidinae), and the Archaeaspididae, next to the Nevadiidae, the Neltneriidae and the Judomiidae.[2] This opinion was reflected in the Revised Treatise of 1997.[3]

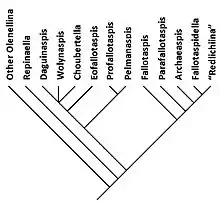

More recent cladistic analysis suggests that the ”Fallotaspidoidea” are the sister group of all other Olenellina (Judomiidoidea, Nevadiidoidea and Olenelloidea). The ”Fallotaspidoidea” remain paraphyletic (hence the quotation marks),[10] even after reorganizing it, because it gave rise to the trilobites with dorsal sutures. Applying a strictly cladistic approach would call for including the ”Fallotaspidoidea” in the Redlichiina, and possibly raising the status of the remaining Olenellina to become an order (and be renamed to Olenellida).[1]

Relations within the ”Fallotaspidoidea”

Repinaella is closest to the common ancestor with the other Olenellina. Second to split away is the Daguinaspididae-family, which comprises the closely knit group of Choubertella, Daguinaspis and Wolynaspis, with Eofallotaspis slightly further removed, and near the basis a subgroup consisting of Profallotaspis and Pelmanaspis. The monotypical family Fallotaspididae is next to branch-off. This is followed by the branch of Parafallotaspis all on its own, followed by the monotypical family Archaeaspididae. Finally Fallotaspidella is closest to the trilobites with dorsal cephalic sutures, such as Bigotina and Lemdadella.[1]

Genera previously assigned to the ”Fallotaspidoidea”

Bradyfallotaspis fusa, Geraldinella corneiliana and Selindella gigantea, all have a long frontal glabellar lobe (L4), and eye ridges that contact only the posterior part of L4, and so these genera belong to the “Nevadioidea“.[1]

Description

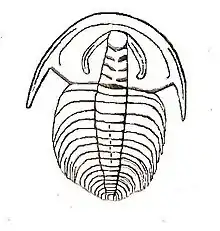

As with most early trilobites, the Fallotaspidoidea have an almost flat exoskeleton, that is only thinly calcified, and has crescent-shaped eye ridges. As part of the Olenellina suborder, the Fallotaspidoidea lack dorsal sutures. The superfamily can be distinguished from all other Olenellina by features of the cephalon and in particular the glabella. The glabella tapers forward. The frontal lobe of the glabella (because it is counted from the back, it is numbered L4) is as long as the most backward lobe (L0), less than in the other Olenellina. The eye ridges (or ocular lobes) contact, but do not merge with, the entire frontal margin of the glabella.[11]

Key to the genera

This key complements the key in the Olenellina article.

| 1 | A parafrontal band prominent. The area between the eye ridge and the glabella (or interocular area) is at least as wide as the eye ridge (or ocular lobe) at midlength. → 2 |

|---|---|

| - | No parafrontal band visible in dorsal view. The interocular area ½-⅓× as wide as the ocular lobe at midlength. → Repinaella siberica |

| 2 | The ridge bordering the head shield (or anterior border) in front of the sides of the glabella is at most half as wide as the most backward lobe of the glabella (occipital ring or L0). → 3 |

| - | The anterior border is at least ¾× as wide as L0. → 8 |

| 3 | The anterior border is not separated from the area it encloses (the extra-ocular area) by a furrow. The interocular area 2-3× as wide as the ocular lobe at midlength. The outward sections of the furrow between the second and third pair of side lobes of the glabella (S2) are directed backward at 35°-45° relative to the transverse line. → 4 |

| - | The anterior border is prominently separated from the extra-ocular area by a furrow. The interocular area 1-1½× as wide as the ocular lobe at midlength. (S2) is directed backward at about 10°. → 7 |

| 4 | The cephalon does not carry two backward directed spines that are a continuation of the lateral raised borders (or genal spines). The furrow between the first and second pair of side lobes of the glabella (S1) is transverse or faintly convex anteriorly. The outer band of the eye ridge (or ocular lobe) near the side of the frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) expands prominently. No antero-lateral lobes on L0 and L1. → 5 |

| - | Genal spines present. S1 sinuous. The outer band of the ocular lobe near the side of L4 does not expand. Antero-lateral lobes on L0 and L1. → Eofallotaspis tioutensis |

| 5 | The space between the cephalic border and the front of the glabella (or preglabellar field) distinctly longer than the most backward lobe of the glabella (occipital ring or L0). The glabella is moderately to strongly tapered forward. → 6 |

| - | The glabella is gently tapered forward. Preglabellar field not longer than L0. → Wolynaspis unica |

| 6 | The distance between the anterior cephalic border and the frontal lobe of the glabella (or preglabellar field) is approximately equal to the length of L0. The anterior cephalic border is a flattened ledge. L0 is smooth or has a faint node. The segments of the thorax axis are smooth or have a faint node. The tail shield (or pygidium) consists of one poorly defined ring and terminal segment. → Daguinaspis ambroggii |

| - | The preglabellar field is 1½-2× the length of L0. The anterior cephalic border is a rounded ridge. L0 carries a backward directed spine at midline. Four to five rings can clearly distinguished in the pygidium. → Choubertella spinosa |

| 7 | The area between the ocular lobe and the lateral border of the cephalon (or extra-ocular area) ⅓-½× the width of the glabella opposite L1. → Pelmanaspis jurii |

| - | Ocular lobe (almost) in contact with the lateral border. → Profallotaspis jakutensis |

| 8 | The frontal lobe of the glabella (L4) is connected with the border surrounding the cephalon with a short ridge on the midline (the so-called “plectrum”). → 9 |

| - | Plectrum absent. → Fallotaspis |

| 9 | The distance between the anterior cephalic border and the frontal lobe of the glabella (or preglabellar field) is ¼-1¼× the length of L0. The anterior tip of the visual surface is opposite or posterior of the point S3 meets the furrow defining the glabella. → 10 |

| - | The preglabellar field) is 1½-2× the length of L0. The anterior tip of the visual surface is anterior of the side of S3. → Parafallotaspis grata |

| 10 | A ridge is developed between the ocular lobe and the glabella. The posterior tips of the ocular lobes are opposite the middle of the distal margin of the occipital ring (or L0). → Archaeaspis |

| - | Mid-interocular ridge absent. The posterior tips of the ocular lobes are anterior of L0. → Fallotaspidella musatovi[1] |

References

- Lieberman, B.S. (2002). "Phylogenetic analysis of some basal early Cambrian Trilobites, the biogeographic origins of the Eutrilobites, and the timing of the Cambrian radiation" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 76 (4): 692–708. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0692:paosbe>2.0.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-12. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- Palmer, A.R.; Repina, L.N. (1993), "Through a Glass Darkly: Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Biostratigraphy of the Olenellina", The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions, 3: 1–35

- Whittington, H. B. et al. Part O, Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Revised, Volume 1 – Trilobita – Introduction, Order Agnostida, Order Redlichiida. 1997

- Hupé, Pierre (1953). "Contribution a l'étude du Cambrien Inférieur et du Précambrien III de l'Anti-Atlas Marocain". Service Géologique du Maroc, Notes et Mémoires. 103: 1–402.

cited in Palmer and Repina, 1993

- Moore, R.C. (ed.). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part O – Arthropoda (Trilobitomorpha). 1959

- Chetnysheva, N.E. (1960). "Chlenistonogie, trilobitoobraznye i rakoobraznye [Arthropoda: Trilobitomorpha and Crustacea]". Osnovy Paleontologii [Fundamentals of Paleontology]. Moscow: Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Ministerstvo Geologii i Okhrany Nedr SSSR. p. 515.

cited in Palmer and Repina, 1993

- Bergstrom, J., 1973. Classification of olenellid trilobites and some Balto-Scandian species. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift 53:283-314|cited in Palmer and Repina, 1993

- Repina, L.N. (1979). "Zavisimost morfologicheskikh priznakov ot uslovii obitaniia trilobitov i otsenka ikh znacheniia dlia sistematiki nadsemeistva Olenelloidea [Dependence of morphologic features on habitat conditions in trilobites and evaluation of their significance for the systematics of the superfamily Olenelloidea]". Akademiia Nauk SSSR, Sibirskoe Otdelenie, Trudy Instituta Geologii I Geofizikii. 431: 11–30.

cited in Palmer and Repina, 1993

- Ahlberg, P.; Bergström, J.; Johansson, J. (1986). "Lower Cambrian olenellid trilobites from the Baltic faunal province". Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar. 108: 39–56. doi:10.1080/11035898609453745.

cited in Palmer and Repina, 1993

- Wiley, E.O. (1979). "An annotated Linnaean hierarchy, with comments on natural taxa and competing systems". Systematic Zoology. 28 (3): 308–337. doi:10.1093/sysbio/28.3.308.

cited in Lieberman, 2002

- Lieberman, B. S. (1998). "Cladistic analysis of the Early Cambrian olenelloid trilobites". Journal of Paleontology. 72: 59–78. doi:10.1017/S0022336000024021.