Devonian

The Devonian (/dɪˈvoʊ.ni.ən, də-, dɛ-/ dih-VOH-nee-ən, də-, deh-)[8][9] is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic, spanning 60 million years from the end of the Silurian, 419.2 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, 358.9 Mya.[10] It is named after Devon, England, where rocks from this period were first studied.

| Devonian | |

|---|---|

| 419.2 ± 3.2 – 358.9 ± 0.4 Ma | |

| Chronology | |

Events of the Devonian Period -420 — – -415 — – -410 — – -405 — – -400 — – -395 — – -390 — – -385 — – -380 — – -375 — – -370 — – -365 — – -360 — – Key events of the Devonian Period. Axis scale: millions of years ago. | |

| Etymology | |

| Name formality | Formal |

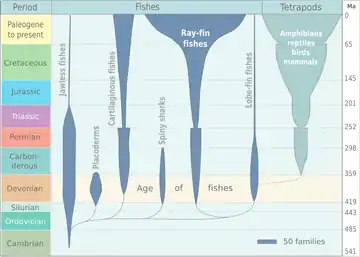

| Nickname(s) | Age of Fishes |

| Usage information | |

| Celestial body | Earth |

| Regional usage | Global (ICS) |

| Time scale(s) used | ICS Time Scale |

| Definition | |

| Chronological unit | Period |

| Stratigraphic unit | System |

| Time span formality | Formal |

| Lower boundary definition | FAD of the Graptolite Monograptus uniformis |

| Lower boundary GSSP | Klonk, Prague, Czechia 49.8550°N 13.7920°E |

| GSSP ratified | 1972[4] |

| Upper boundary definition | FAD of the Conodont Siphonodella sulcata (discovered to have biostratigraphic issues as of 2006).[5] |

| Upper boundary GSSP | La Serre, Montagne Noire, France 43.5555°N 3.3573°E |

| GSSP ratified | 1990[6] |

| Atmospheric and climatic data | |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content | c. 15 vol % (75 % of modern) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content | c. 2200 ppm (8 times pre-industrial) |

| Mean surface temperature | c. 20 °C (6 °C above modern) |

| Sea level above present day | Relatively steady around 189m, gradually falling to 120m through period[7] |

The first significant adaptive radiation of life on dry land occurred during the Devonian. Free-sporing vascular plants began to spread across dry land, forming extensive forests which covered the continents. By the middle of the Devonian, several groups of plants had evolved leaves and true roots, and by the end of the period the first seed-bearing plants appeared. Various terrestrial arthropods also became well-established.

Fish reached substantial diversity during this time, leading the Devonian to often be dubbed the Age of Fishes. The placoderms began dominating almost every known aquatic environment. The ancestors of all four-limbed vertebrates (tetrapods) began adapting to walking on land, as their strong pectoral and pelvic fins gradually evolved into legs.[11] In the oceans, primitive sharks became more numerous than in the Silurian and Late Ordovician.

The first ammonites, species of molluscs, appeared. Trilobites, the mollusc-like brachiopods, and the great coral reefs were still common. The Late Devonian extinction which started about 375 million years ago[12] severely affected marine life, killing off all placodermi, and all trilobites, save for a few species of the order Proetida.

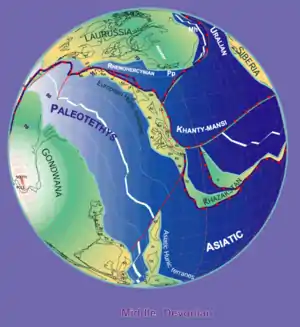

The palaeogeography was dominated by the supercontinent of Gondwana to the south, the continent of Siberia to the north, and the early formation of the small continent of Euramerica in between.

History

The period is named after Devon, a county in southwestern England, where a controversial argument in the 1830s over the age and structure of the rocks found distributed throughout the county was eventually resolved by the definition of the Devonian period in the geological timescale. The Great Devonian Controversy was a long period of vigorous argument and counter-argument between the main protagonists of Roderick Murchison with Adam Sedgwick against Henry De la Beche supported by George Bellas Greenough. Murchison and Sedgwick won the debate and named the period they proposed as the Devonian System.[13][14][lower-alpha 1]

While the rock beds that define the start and end of the Devonian period are well identified, the exact dates are uncertain. According to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, [18] the Devonian extends from the end of the Silurian 419.2 Mya, to the beginning of the Carboniferous 358.9 Mya – in North America, at the beginning of the Mississippian subperiod of the Carboniferous.

In nineteenth-century texts the Devonian has been called the "Old Red Age", after the red and brown terrestrial deposits known in the United Kingdom as the Old Red Sandstone in which early fossil discoveries were found. Another common term is "Age of the Fishes",[19] referring to the evolution of several major groups of fish that took place during the period. Older literature on the Anglo-Welsh basin divides it into the Downtonian, Dittonian, Breconian, and Farlovian stages, the latter three of which are placed in the Devonian.[20]

The Devonian has also erroneously been characterised as a "greenhouse age", due to sampling bias: most of the early Devonian-age discoveries came from the strata of western Europe and eastern North America, which at the time straddled the Equator as part of the supercontinent of Euramerica where fossil signatures of widespread reefs indicate tropical climates that were warm and moderately humid but in fact the climate in the Devonian differed greatly during its epochs and between geographic regions. For example, during the Early Devonian, arid conditions were prevalent through much of the world including Siberia, Australia, North America, and China, but Africa and South America had a warm temperate climate. In the Late Devonian, by contrast, arid conditions were less prevalent across the world and temperate climates were more common.

Subdivisions

The Devonian Period is formally broken into Early, Middle and Late subdivisions. The rocks corresponding to those epochs are referred to as belonging to the Lower, Middle and Upper parts of the Devonian System.

- Early Devonian

The Early Devonian lasted from 419.2 ± 2.8 to 393.3 ± 2.5 and began with the Lochkovian stage 419.2 ± 2.8 to 410.8 ± 2.5, which was followed by the Pragian from 410.8 ± 2.8 to 407.6 ± 2.5 and then by the Emsian, which lasted until the Middle Devonian began, 393.3± 2.7 million years ago.[21] During this time, the first ammonoids appeared, descending from bactritoid nautiloids. Ammonoids during this time period were simple and differed little from their nautiloid counterparts. These ammonoids belong to the order Agoniatitida, which in later epochs evolved to new ammonoid orders, for example Goniatitida and Clymeniida. This class of cephalopod molluscs would dominate the marine fauna until the beginning of the Mesozoic era.

- Middle Devonian

The Middle Devonian comprised two subdivisions: first the Eifelian, which then gave way to the Givetian 387.7± 2.7 million years ago. During this time the jawless agnathan fishes began to decline in diversity in freshwater and marine environments partly due to drastic environmental changes and partly due to the increasing competition, predation, and diversity of jawed fishes. The shallow, warm, oxygen-depleted waters of Devonian inland lakes, surrounded by primitive plants, provided the environment necessary for certain early fish to develop such essential characteristics as well developed lungs, and the ability to crawl out of the water and onto the land for short periods of time.[22]

- Late Devonian

Finally, the Late Devonian started with the Frasnian, 382.7 ± 2.8 to 372.2 ± 2.5, during which the first forests took shape on land. The first tetrapods appeared in the fossil record in the ensuing Famennian subdivision, the beginning and end of which are marked with extinction events. This lasted until the end of the Devonian, 358.9± 2.5 million years ago.[21]

Climate

The Devonian was a relatively warm period, and probably lacked any glaciers. The temperature gradient from the equator to the poles was not as large as it is today. The weather was also very arid, mostly along the equator where it was the driest.[23] Reconstruction of tropical sea surface temperature from conodont apatite implies an average value of 30 °C (86 °F) in the Early Devonian.[23] CO

2 levels dropped steeply throughout the Devonian period. The newly evolved forests drew carbon out of the atmosphere, which were then buried into sediments. This may be reflected by a Mid-Devonian cooling of around 5 °C (9 °F).[23] The Late Devonian warmed to levels equivalent to the Early Devonian; while there is no corresponding increase in CO

2 concentrations, continental weathering increases (as predicted by warmer temperatures); further, a range of evidence, such as plant distribution, points to a Late Devonian warming.[23] The climate would have affected the dominant organisms in reefs; microbes would have been the main reef-forming organisms in warm periods, with corals and stromatoporoid sponges taking the dominant role in cooler times. The warming at the end of the Devonian may even have contributed to the extinction of the stromatoporoids.

Paleogeography

The Devonian period was a time of great tectonic activity, as Euramerica and Gondwana drew closer together.

The continent Euramerica (or Laurussia) was created in the early Devonian by the collision of Laurentia and Baltica, which rotated into the natural dry zone along the Tropic of Capricorn, which is formed as much in Paleozoic times as nowadays by the convergence of two great air-masses, the Hadley cell and the Ferrel cell. In these near-deserts, the Old Red Sandstone sedimentary beds formed, made red by the oxidised iron (hematite) characteristic of drought conditions.[24]

Near the equator, the plate of Euramerica and Gondwana were starting to meet, beginning the early stages of the assembling of Pangaea. This activity further raised the northern Appalachian Mountains and formed the Caledonian Mountains in Great Britain and Scandinavia.

The west coast of Devonian North America, by contrast, was a passive margin with deep silty embayments, river deltas and estuaries, found today in Idaho and Nevada; an approaching volcanic island arc reached the steep slope of the continental shelf in Late Devonian times and began to uplift deep water deposits, a collision that was the prelude to the mountain-building episode at the beginning of the Carboniferous called the Antler orogeny.[25]

Sea levels were high worldwide, and much of the land lay under shallow seas, where tropical reef organisms lived. The deep, enormous Panthalassa (the "universal ocean") covered the rest of the planet. Other minor oceans were the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, Proto-Tethys Ocean, Rheic Ocean, and Ural Ocean (which was closed during the collision with Siberia and Baltica).

During the Devonian, Chaitenia, an island arc, accreted to Patagonia.[26]

Life

Marine biota

Sea levels in the Devonian were generally high. Marine faunas continued to be dominated by bryozoa, diverse and abundant brachiopods, the enigmatic hederellids, microconchids and corals. Lily-like crinoids (animals, their resemblance to flowers notwithstanding) were abundant, and trilobites were still fairly common. Among vertebrates, jawless armored fish (ostracoderms) declined in diversity, while the jawed fish (gnathostomes) simultaneously increased in both the sea and fresh water. Armored placoderms were numerous during the lower stages of the Devonian Period and became extinct in the Late Devonian, perhaps because of competition for food against the other fish species. Early cartilaginous (Chondrichthyes) and bony fishes (Osteichthyes) also become diverse and played a large role within the Devonian seas. The first abundant genus of shark, Cladoselache, appeared in the oceans during the Devonian Period. The great diversity of fish around at the time has led to the Devonian being given the name "The Age of Fish" in popular culture.[28]

The first ammonites also appeared during or slightly before the early Devonian Period around 400 Mya.[29]

Reefs

A now dry barrier reef, located in present-day Kimberley Basin of northwest Australia, once extended 350 km (220 mi), fringing a Devonian continent.[30] Reefs in general are built by various carbonate-secreting organisms that have the ability to erect wave-resistant structures close to sea level. Although modern reefs are constructed mainly by corals and calcareous algae, Devonian reefs were either microbial reefs built up mostly by autotrophic cyanobacteria, or coral-stromatoporoid reefs built up by coral-like stromatoporoids and tabulate and rugose corals. Microbial reefs dominated under the warmer conditions of the early and late Devonian, while coral-stromatoporoid reefs dominated during the cooler middle Devonian.[31]

Terrestrial biota

By the Devonian Period, life was well underway in its colonisation of the land. The moss forests and bacterial and algal mats of the Silurian were joined early in the period by primitive rooted plants that created the first stable soils and harbored arthropods like mites, scorpions, trigonotarbids[32] and myriapods (although arthropods appeared on land much earlier than in the Early Devonian[33] and the existence of fossils such as Protichnites suggest that amphibious arthropods may have appeared as early as the Cambrian). By far the largest land organism at the beginning of this period was the enigmatic Prototaxites, which was possibly the fruiting body of an enormous fungus,[34] rolled liverwort mat,[35] or another organism of uncertain affinities[36] that stood more than 8 metres (26 ft) tall, and towered over the low, carpet-like vegetation during the early part of the Devonian. Also the first possible fossils of insects appeared around 416 Mya, in the Early Devonian. Evidence for the earliest tetrapods takes the form of trace fossils in shallow lagoon environments within a marine carbonate platform / shelf during the Middle Devonian,[37] although these traces have been questioned and an interpretation as fish feeding traces (Piscichnus) has been advanced.[38]

The greening of land

Many Early Devonian plants did not have true roots or leaves like extant plants although vascular tissue is observed in many of those plants. Some of the early land plants such as Drepanophycus likely spread by vegetative growth and spores.[39] The earliest land plants such as Cooksonia consisted of leafless, dichotomous axes and terminal sporangia and were generally very short-statured, and grew hardly more than a few centimetres tall.[40] By the Middle Devonian, shrub-like forests of primitive plants existed: lycophytes, horsetails, ferns, and progymnosperms had evolved. Most of these plants had true roots and leaves, and many were quite tall. The earliest-known trees appeared in the Middle Devonian[41] These included a lineage of lycopods and another arborescent, woody vascular plant, the cladoxylopsids.[42] These tracheophytes were able to grow to large size on dry land because they had evolved the ability to biosynthesize lignin, which gave them physical rigidity and improved the effectiveness of their vascular system while giving them resistance to pathogens and herbivores.[43] These are the oldest-known trees of the world's first forests. By the end of the Devonian, the first seed-forming plants had appeared. This rapid appearance of so many plant groups and growth forms has been called the "Devonian Explosion".

The 'greening' of the continents acted as a carbon sink, and atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide may have dropped. This may have cooled the climate and led to a massive extinction event. See Late Devonian extinction.

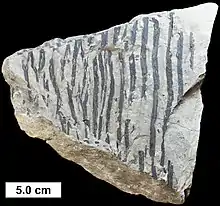

Lycopod axis (branch) from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin

Lycopod axis (branch) from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin Bark (possibly from a cladoxylopsid) from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin

Bark (possibly from a cladoxylopsid) from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin

Animals and the first soils

Primitive arthropods co-evolved with this diversified terrestrial vegetation structure. The evolving co-dependence of insects and seed-plants that characterised a recognisably modern world had its genesis in the Late Devonian period. The development of soils and plant root systems probably led to changes in the speed and pattern of erosion and sediment deposition. The rapid evolution of a terrestrial ecosystem that contained copious animals opened the way for the first vertebrates to seek out a terrestrial living. By the end of the Devonian, arthropods were solidly established on the land.[44]

Gallery

Dunkleosteus, one of the largest armoured fish ever to roam the planet, lived during the Late Devonian

Dunkleosteus, one of the largest armoured fish ever to roam the planet, lived during the Late Devonian Lower jaw of Eastmanosteus pustulosus from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin

Lower jaw of Eastmanosteus pustulosus from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin Tooth of the lobe-finned fish Onychodus from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin

Tooth of the lobe-finned fish Onychodus from the Middle Devonian of Wisconsin Early shark Cladoselache, several lobe-finned fishes, including Eusthenopteron that was an early marine tetrapod, and the placoderm Bothriolepis in a painting from 1905

Early shark Cladoselache, several lobe-finned fishes, including Eusthenopteron that was an early marine tetrapod, and the placoderm Bothriolepis in a painting from 1905

Enrolled phacopid trilobite from the Devonian of Ohio

Enrolled phacopid trilobite from the Devonian of Ohio The common tabulate coral Aulopora from the Middle Devonian of Ohio – view of colony encrusting a brachiopod valve

The common tabulate coral Aulopora from the Middle Devonian of Ohio – view of colony encrusting a brachiopod valve Tropidoleptus carinatus, an orthid brachiopod from the Middle Devonian of New York.

Tropidoleptus carinatus, an orthid brachiopod from the Middle Devonian of New York. Pleurodictyum americanum, Kashong Shale, Middle Devonian of New York

Pleurodictyum americanum, Kashong Shale, Middle Devonian of New York SEM image of a hederelloid from the Devonian of Michigan (largest tube diameter is 0.75 mm)

SEM image of a hederelloid from the Devonian of Michigan (largest tube diameter is 0.75 mm) Devonian spiriferid brachiopod from Ohio which served as a host substrate for a colony of hederelloids

Devonian spiriferid brachiopod from Ohio which served as a host substrate for a colony of hederelloids

Late Devonian extinction

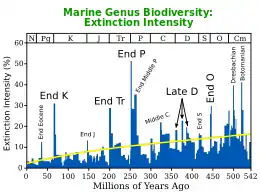

A major extinction occurred at the beginning of the last stage of the Devonian period, the Famennian faunal stage (the Frasnian-Famennian boundary), about 372.2 Mya, when all the fossil agnathan fishes, save for the psammosteid heterostraci, suddenly disappeared. A second strong pulse closed the Devonian period. The Late Devonian extinction was one of five major extinction events in the history of the Earth's biota, and was more drastic than the familiar extinction event that closed the Cretaceous.

The Devonian extinction crisis primarily affected the marine community, and selectively affected shallow warm-water organisms rather than cool-water organisms. The most important group to be affected by this extinction event were the reef-builders of the great Devonian reef systems.

Amongst the severely affected marine groups were the brachiopods, trilobites, ammonites, conodonts, and acritarchs, as well as jawless fish, and all placoderms. Land plants as well as freshwater species, such as our tetrapod ancestors, were relatively unaffected by the Late Devonian extinction event (there is a counterargument that the Devonian extinctions nearly wiped out the tetrapods[45]).

The reasons for the Late Devonian extinctions are still unknown, and all explanations remain speculative. Canadian paleontologist Digby McLaren suggested in 1969, that the Devonian extinction events were caused by an asteroid impact. However, while there were Late Devonian collision events (see the Alamo bolide impact), little evidence supports the existence of a large enough Devonian crater.

See also

- Falls of the Ohio State Park – State park in Indiana, United States, Indiana, United States. One of the largest exposed Devonian fossil beds in the world.

- Geologic time scale – system that relates geological strata to time

- List of Early Devonian land plants

- List of fossil sites – A table of worldwide localities notable for the presence of fossils (with link directory)

- Phacops rana, a Devonian trilobite.

Categories:

- :Category:Devonian plants

Notes

- Sedgwick and Murchison coined the term "Devonian system" in 1840:[15] "We propose therefore, for the future, to designate these groups collectively by the name Devonian system". Sedgwick and Murchison acknowledged William Lonsdale's role in proposing, on the basis of fossil evidence, the existence of a Devonian stratum between those of the Silurian and Carboniferous periods:[16] "Again, Mr. Lonsdale, after an extensive examination of the fossils of South Devon, had pronounced them, more than a year since, to form a group intermediate between those of the Carboniferous and Silurian systems". William Lonsdale stated that in December 1837 he had suggested the existence of a stratum between the Silurian and Carboniferous ones:[17] "Mr. Austen's communication [was] read December 1837 ... . It was immediately after the reading of that paper ... that I formed the opinion relative to the limestones of Devonshire being of the age of the old red sandstone; and which I afterwards suggested first to Mr. Murchison and then to Prof. Sedgwick".

References

- Parry, S. F.; Noble, S. R.; Crowley, Q. G.; Wellman, C. H. (2011). "A high-precision U–Pb age constraint on the Rhynie Chert Konservat-Lagerstätte: time scale and other implications". Journal of the Geological Society. London: Geological Society. 168 (4): 863–872. doi:10.1144/0016-76492010-043.

- Kaufmann, B.; Trapp, E.; Mezger, K. (2004). "The numerical age of the Upper Frasnian (Upper Devonian) Kellwasser horizons: A new U-Pb zircon date from Steinbruch Schmidt(Kellerwald, Germany)". The Journal of Geology. 112 (4): 495–501. Bibcode:2004JG....112..495K. doi:10.1086/421077.

- Algeo, T. J. (1998). "Terrestrial-marine teleconnections in the Devonian: links between the evolution of land plants, weathering processes, and marine anoxic events". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 353 (1365): 113–130. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0195.

- Chlupáč, Ivo; Hladil, Jindrich (January 2000). "The global stratotype section and point of the Silurian-Devonian boundary". CFS Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Kaiser, Sandra (1 April 2009). "The Devonian/Carboniferous boundary stratotype section (La Serre, France) revisited". Newsletters on Stratigraphy. 43 (2): 195–205. doi:10.1127/0078-0421/2009/0043-0195. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Paproth, Eva; Feist, Raimund; Flajs, Gerd (December 1991). "Decision on the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary stratotype" (PDF). Episodes. 14 (4): 331–336. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1991/v14i4/004.

- Haq, B. U.; Schutter, SR (2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–68. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639. S2CID 206514545.

- Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "Devonian". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Gradstein, Felix M.; Ogg, James G.; Smith, Alan G. (2004). A Geologic Time Scale 2004. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521786737.

- Amos, Jonathan. "Fossil tracks record 'oldest land-walkers'". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- Newitz, Annalee (13 June 2013). "How do you have a mass extinction without an increase in extinctions?". The Atlantic.

- Gradstein, Ogg & Smith (2004)

- Rudwick, M.S.J. (1985). The great Devonian controversy: The shaping of scientific knowledge among gentlemanly specialists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226731025.

- Sedgwick, Adam; Murchison, Roderick Impey (1840). "On the physical structure of Devonshire, and on the subdivisions and geological relations of its older stratified deposits, etc. Part I and Part II". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. Second series. Volume 5 part II. p. 701.

- Sedgwick & Murchison 1840, p. 690.

- Lonsdale, William (1840). "Notes on the age of limestones from south Devonshire". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. Second series. Volume 5 part II. p. 724.

- Gradstein, Ogg & Smith 2004.

- Farabee, Michael J. (2006). "Paleobiology: The Late Paleozoic: Devonian". The Online Biology Book. Estrella Mountain Community College.

- Barclay, W.J. (1989). Geology of the South Wales Coalfield Part II, the country around Abergavenny. Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheet (England and Wales) (3rd ed.). pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-11-884408-3.

- Cohen, K.M.; Finney, S.C.; Gibbard, P.L.; Fan, J.-X. (2013). "The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). Episodes. 36 (3): 199–204. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Clack, Jennifer (13 August 2007). "Devonian climate change, breathing, and the origin of the tetrapod stem group". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (4): 510–523. doi:10.1093/icb/icm055. PMID 21672860.

Estimates of oxygen levels during this period suggest that they were unprecedentedly low during the Givetian and Frasnian periods. At the same time, plant diversification was at its most rapid, changing the character of the landscape and contributing, via soils, soluble nutrients, and decaying plant matter, to anoxia in all water systems. The co-occurrence of these global events may explain the evolution of air-breathing adaptations in at least two lobe-finned groups, contributing directly to the rise of the tetrapod stem group.

- Joachimski, M. M.; Breisig, S.; Buggisch, W. F.; Talent, J. A.; Mawson, R.; Gereke, M.; Morrow, J. R.; Day, J.; Weddige, K. (July 2009). "Devonian climate and reef evolution: Insights from oxygen isotopes in apatite". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 284 (3–4): 599–609. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.284..599J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.028.

- "Devonian Period". Encyclopedia Britannica. geochronology. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Blakey, Ron C. "Devonian Paleogeography, Southwestern US". jan.ucc.nau.edu. Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010.

- Hervé, Francisco; Calderón, Mauricio; Fanning, Mark; Pankhurst, Robert; Rapela, Carlos W.; Quezada, Paulo (2018). "The country rocks of Devonian magmatism in the North Patagonian Massif and Chaitenia". Andean Geology. 45 (3): 301–317. doi:10.5027/andgeoV45n3-3117.

- Benton, M. J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology (3rd ed.). John Wiley. p. 14. ISBN 9781405144490.

- Dalton, Rex (January 2006). "Hooked on fossils". Nature. 439 (7074): 262–263. doi:10.1038/439262a. PMID 16421540. S2CID 4357313.

- Kazlev, M. Alan (May 28, 1998). "Palaeos Paleozoic: Devonian: The Devonian Period – 1". Palaeos. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Tyler, Ian M.; Hocking, Roger M.; Haines, Peter W. (1 March 2012). "Geological evolution of the Kimberley region of Western Australia". Episodes. 35 (1): 298–306. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2012/v35i1/029.

- Joachimski, M.M.; Breisig, S.; Buggisch, W.; Talent, J.A.; Mawson, R.; Gereke, M.; Morrow, J.R.; Day, J.; Weddige, K. (July 2009). "Devonian climate and reef evolution: Insights from oxygen isotopes in apatite". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 284 (3–4): 599–609. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.284..599J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.028.

- Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason (July 2014). "The walking dead: Blender as a tool for paleontologists with a case study on extinct arachnids". Journal of Paleontology. 88 (4): 735–746. doi:10.1666/13-088. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 131202472. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (September 2011). "Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Uncertainty". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 4 (3): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y.

- Hueber, Francis M. (2001). "Rotted wood-alga fungus: The history and life of Prototaxites Dawson 1859". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 116 (1–2): 123–159. doi:10.1016/s0034-6667(01)00058-6.

- Graham, Linda E.; Cook, Martha E.; Hanson, David T.; Pigg, Kathleen B.; Graham, James M. (2010). "Rolled liverwort mats explain major Prototaxites features: Response to commentaries". American Journal of Botany. 97 (7): 1079–1086. doi:10.3732/ajb.1000172. PMID 21616860.

- Taylor, Thomas N.; Taylor, Edith L.; Decombeix, Anne-Laure; Schwendemann, Andrew; Serbet, Rudolph; Escapa, Ignacio; Krings, Michael (2010). "The enigmatic Devonian fossil Prototaxites is not a rolled-up liverwort mat: Comment on the paper by Graham et al.(AJB 97: 268–275)". American Journal of Botany. 97 (7): 1074–1078. doi:10.3732/ajb.1000047. PMID 21616859.

- Niedźwiedzki (2010). "Tetrapod trackways from the early middle Devonian period of Poland". Nature. 463 (7277): 43–48. Bibcode:2010Natur.463...43N. doi:10.1038/nature08623. PMID 20054388. S2CID 4428903.

- Lucas (2015). "Thinopus and a Critical Review of Devonian Tetrapod Footprints". Ichnos. 22 (3–4): 136–154. doi:10.1080/10420940.2015.1063491. S2CID 130053031.

- Zhang, Ying-ying; Xue, Jin-Zhuang; Liu, Le; Wang, De-ming (2016). "Periodicity of reproductive growth in lycopsids: An example from the Upper Devonian of Zhejiang Province, China". Paleoworld. 25 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2015.07.002.

- Gonez, Paul; Gerrienne, Philippe (2010). "A new definition and a lectotypification of the genus Cooksonia Lang 1937". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 171 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1086/648988. S2CID 84956576.

- Smith, Lewis (19 April 2007). "Fossil from a forest that gave Earth its breath of fresh air". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Fern". In Basu, Saikat; Cleveland, C. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington DC: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- Weng, Jing-Ke; Chapple, Clint (July 2010). "The origin and evolution of lignin biosynthesis: Tansley review". New Phytologist. 187 (2): 273–285. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03327.x. PMID 20642725.

- Gess, R.W. (2013). "The earliest record of terrestrial animals in Gondwana: A scorpion from the Famennian (Late Devonian) Witpoort Formation of South Africa". African Invertebrates. 54 (2): 373–379. doi:10.5733/afin.054.0206.

- McGhee, George R. (2013). When the invasion of land failed: The legacy of the Devonian extinctions. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231160568.

External links

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleozoic#Devonian |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Devonian. |

- "Devonian". Devonian Times. Archived from the original on 2010-02-11.

- "Devonian life". UC Berkeley. – site introduces the Devonian

- "Geologic Time Scale". International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). 2004. Retrieved 19 September 2005.

- "Examples of Devonian Fossils".

- "Devonian chronostratigraphy scale".

- "Devonian". Palaeos. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007.

- "Museum". Age of Fishes.