Feminine beauty ideal

The feminine beauty ideal is "the socially constructed notion that physical attractiveness is one of women's most important assets, and something all women should strive to achieve and maintain".[1]

Feminine beauty ideals can be rooted in heteronormative beliefs, and they heavily influence women of all sexual orientations. The feminine beauty ideal, which also includes female body shape, varies from culture to culture.[2] Pressure to conform to a certain definition of "beautiful" can have psychological effects, such as depression, eating disorders, and low self-esteem, starting from an adolescent age and continuing into adulthood.

From an evolutionary perspective, some perceptions of feminine beauty ideals correlate with fertility and health.

Across cultures

General

There have been many ideas over time and across different cultures of what the feminine beauty ideal is for a woman's body image. How well a woman follows these beauty ideals can also influence her social status within her culture. Physically altering the body has been a custom in many areas of the world for a long time. In Burma, Padung girls from the age of about five years, have metal rings put around their necks. Additional rings are added to the girl's neck every two years. This practice is done to produce a giraffe-like effect in women. This practice is dying out, but these women would eventually carry up to 24 rings around their necks. A neck with many rings was considered the "ideal" image of physical beauty in this culture. In Europe, the corset has been used over time to create a tiny waistline. In Europe, a tiny waistline was considered "ideal" for beauty. A practice in China involved a girl's feet being bound at age six to create the "ideal" image of feet. The girl's feet were bound to become 1/3 the original size, which crippled the woman, but also gave her a very high social status and was much admired. After the revolution of 1911, this practice of foot binding was ended. The idea of what is considered the ideal of beauty for women varies across different cultural ideals and practices.[3]

Asian women

Asia is considered to have strict beauty standards, such as fair skin, full lips, strong eyebrows, defined cheekbones, poreless skin, and shiny hair.[4] More particularly, South Korea is known for its unrealistic beauty standards, transforming the skincare industry.[5] They seek a doll-like look, defined by a "very pale skin, big eyes with double eyelids, a tiny nose with a high nose bridge, and rosebud lips", a small face and subtly pointed chin.[4] As these standards are difficult to achieve, cosmetic surgery became very popular. South Korea has the highest rate of cosmetic surgery per capita, and it keeps rising.[6]

French women

There have been multiple beauty ideals for women in France. A more common ideal is for women to have the "three white things". These "things" or traits refer to skin, teeth, and hands. There are also the "three black things", including the color of the person's eyebrows and eyelashes. This leaves three other areas to embark on, including the cheeks, lips, and nails.[7]

According to Wandering Pioneer, beauty standards in France seem to concern someone's style rather than the body shape.[8] In addition, the French approach to beauty is about enhancing natural features rather than achieving a specific look.[9] According to some dermatologists, looking young is not a beauty criterion. Instead, women want to look toned and their skin to look firm.[10]

Black women

Eurocentric features are most desired and socially accepted. Eurocentric beauty paradigms not only often exclude black women (their cultural attire, natural hair types, different skin colors, or various body types), but they also impact black women's identity. Black women whose appearance is socially accepted are exceptions. One study indicated that women with lighter skin tones, long softer hair, and have eurocentric facial features not only gain privileges within their communities but are reported to have higher confidence in themselves, higher self-esteem and individual growth than non-eurocentric featured black women.[11] These beauty ideals are presented in models who are often white or people of color that possess these specific body types and facial Eurocentric features. This has been explained in terms of the intersectionality of racism and sexism black women face almost every day. Intersectionality is a term coined by activist and author Kimberlé Crenshaw, who theorized that to define the intertwined categories of discrimination, one may need to consider intersecting identities of race, class, or gender.

Colorism can be defined as the discrimination or unjust treatment of people within the same racial or ethnic group or community based on the shade of one's color.[12] Colorism can also affect Latin Americans, East Asians, South Asians, and even Europeans, leading to complexion discrimination. One of the major eurocentric features that is desired by society in black women is lighter skin color. Terms such as "redbone", "yellowbone", or "light skin" have been used in films, rap songs, and other forms of entrainment to describe a "beautiful" or "desirable" black women, especially in the black African American communities. Due to the fact that lighter-skinned African Americans are more desired, they tend to have more social and political privileges and advantages that dark African Americans do not. On the other hand, darker-skinned individuals, culturally and ethnically are often viewed as authentic or legitimate compared to lighter-skinned people. Darker African Americans are seen as black with little to no doubt, while lighter-skinned African Americans are most likely questioned or not seen as entirely black.[13] Colorism in the United States dates back to during slavery, where lighter skinned men or women were required to work indoors while the darker skinned individuals were to work out on the fields. The shade of their skin color determined their job as well as the treatment they were to receive.[14] In the documentary film titled "Dark Girls",[15] interviews of black women in the documentary shine light on the unspoken about topic of colorism. Experiences and experiments mentioned in the film conclude how women of darker skin suffered socially, mentally, and personally. Some of the women in the film mention how they did not see themselves are beautiful because of their darker skin.

Black women and women of color, on many platforms and forms of representation, have been whitewashed. Whitewashing of black women is not only limited to whitening black individuals' skin tones, but also giving them straight hair textures and eurocentric features. Magazines and beauty companies have been criticized for whitewashing the images of black female celebrities on covers and advertisements, mostly photoshopping them with lighter skin.[16]

In mass media

Mass media is one of the most powerful tools for young girls and women to learn and also understand feminine beauty ideals. As mass media develops, the way people see feminine beauty ideals changes, as does how females view themselves. "The average teen girl gets about 180 minutes of media exposure daily and only about 10 minutes of parental interaction a day," says Renee Hobbs, EdD, associate professor of communications at Temple University.[17] In most advertisements, female models are typically homogeneous in appearance. "Girls today are swamped by [ultra-thin] ideals not only in the form of dolls but also in comics, cartoons, TV, and advertising along with all the associated merchandising."[18]:290 In addition to this, the feminine beauty ideal in the mass media is manipulated by technology. Images of women can be virtually manipulated creating an ideal that is not only rare but also nonexistent.[19] The Encyclopedia of Gender in the Media states that "the postproduction techniques of airbrushing and computer-generated modifications 'perfect' the beauty myth by removing any remaining blemishes or imperfections visible to the eye."[20] Advertisements for products "such as diets, cosmetics, and exercise gear [help] the media construct a dream world of hopes and high standards that incorporates the glorification of slenderness and weight loss."[21]

With a focus on an ideal physical appearance, the feminine beauty ideal distracts from female competency by prioritizing and valuing superficial characteristics related to beauty and appearance. When physical beauty is idealized and featured in the media, it reduces women to sexualized objects.[22] This creates the message across mass media that one's body is inadequate apart from sex appeal and connects concepts of beauty and sex.[22]

Perfection is achieved by celebrities through photoshopped images that hide every blemish or flaw while also editing body parts to create the ideal hourglass body type. The Dove Beauty and Confidence Report interviewed 10,500 females across thirteen countries and found that women's confidence in their body image is steadily declining – regardless of age or geographic location. Despite these findings, there is a strong desire to fight existing beauty ideals. In fact, 71% of women and 67% of girls want the media to do a better job of portraying different types of women. Studies done by Dove reveal low self esteem impacts women and girls' ability to release their true potential. 85% of women and 79% of girls admit they opt out of important life activities when they do not feel confident in the way they look. More than half of women (69%) and girls (65%) allude to pressure from the media and advertisements to become the world's version of beautiful, which is a driving force of appearance anxiety.[23] Studies done by Dove have also revealed the following statistics: "4% of women consider themselves beautiful, 11% of girls globally are comfortable with describing themselves as beautiful, 72% of girls feel pressure to be beautiful, 80% of women agree that every woman has something about her that is beautiful, but do not see their own beauty, and that 54% of women agree that when it comes to how they look, they are their own worst beauty critic."[24]

An online space such as Instagram that is based on interactions through pictures creates a focus on one’s physical appearance.[25] According to evidence gathered from a study focusing on general Instagram use in young women, researchers suggest Instagram usage was positively correlated with women’s self-objectification.[25] This same study also considered the effect of Instagram on the internalization of the Western beauty ideal for women, and the evidence gathered in the study agrees with the idea that Instagram use encourages women to internalize the societal beauty ideal of Western culture. Because users have the opportunity to shape and edit their photographs before sharing them, they can force them to adhere to the beauty ideal.[25] Viewing these carefully selected pictures shows the extent to which women internalize the Western beauty ideal.[25] In addition to researching the effects of general Instagram use, the study also researched the effects of "fitspiration" Instagram pages on young women's body image. “Fitspiration” pages aim to motivate the viewer through images of healthy eating and exercising.[25] Although these pages aim to be a positive way to promote a healthy lifestyle, they are also appearance-based and contain images of toned and skinny women.[26] According to the study, there is a positive correlation to young women’s viewing "fitspiration" pages and a negative body image.[25]

A case study conducted about Instagram use and the Western feminine beauty ideal focused on the specific account @effyourbeautystandards, a body-positive Instagram page created by feminist plus-size model Tess Holliday.[27] Through her page, Holliday instructed women to share pictures of themselves on Instagram with the hashtag #effyourbeautystandards.[27] Images posted with this hashtag would be selected by the account administrators and posted to the @effyourbeauutystandards page.[27] The evidence gathered in this case study suggested that while these selected pictures attempt to take an intersectional approach to the content women view on social media, they may still have an effect on how women view their bodies.[27]

In fairy tales

The feminine beauty ideal is portrayed in many children's fairy tales.[1] It has been common in the Brothers Grimm fairy tales for physical attractiveness in female characters to be rewarded.[28] In those fairy tales, "beauty is often associated with being white, economically privileged, and virtuous."[28]

The Brothers Grimm fairy tales usually involve a beautiful heroine. In the story Snow White, the protagonist Snow White is described as having "skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood, and hair as black as ebony wood" and as being "beautiful as the light of day."[29] By contrast, the antagonist of Brothers Grimm fairy tales is frequently described as old and physically unattractive, relating beauty with youth and goodness, and ugliness with aging and evil.[28] Ultimately, this correlation puts an emphasis on the virtue of being beautiful, as defined by Grimm fairy tales.

Starting almost 100 years after the Grimm Brothers wrote their fairy tales, the Walt Disney Animation Studios adapted these tales into animated feature films. About 40 percent of Disney films made from 1937–2000 had "only dominant cultural themes portrayed."[30] Because the majority of characters are white, "the expectation [is] that all people are or should be like this."[30] Other common traits of female Disney characters are thin bodies with impossible bodily proportions, long, flowing hair, and large round eyes.[31] The constant emphasis on female beauty and what constitutes as being beautiful contributes to the overall feminine beauty ideal.

Psychological effects

Feminine beauty ideals have shown correlations to many psychological disorders, including lowered self-esteem and eating disorders. Western cultural standards of beauty and attractiveness promote unhealthy and unattainable body ideals that motivate women to seek perfection.[32] Since 1972, there has been a dramatic increase in the percentage of women in the United States who experience dissatisfaction with their bodies.[13] Research indicates that women's exposure to television, even for a very short time, can experience decreased mood and self-esteem.[33] It has been consistently found that perceived appearance is the single strongest predictor of global self-esteem among young adults.[13] Awareness of the ideal female shape is linked to increasingly negative self-esteem.[13] Through peer interaction and an environment of continual comparison to those portrayed in the media, women are often made to feel inadequate, and thus their self-esteem can decrease from their negative self-image. A negative body image can result in adverse psychosocial consequences, including depression, poor self-esteem, and diminished quality of life.[34]

There is significant pressure for girls to conform to feminine beauty ideals, and, since thinness is prized as feminine, many women feel dissatisfied with their body shape. Body dissatisfaction has been found to be a precursor to serious psychological problems such as depression, social anxiety, and eating disorders.[35] The feminine beauty ideal has influenced women, particularly younger women, to partake in extreme measures. Some of these extreme measures include limiting their food intake, and participating in excessive physical activity to try to achieve what is considered the "ideal beauty standards". One aspect of the feminine beauty ideal includes having a thin waist, which is causing women to participate in these alarming behaviors. When trying to achieve these impossible standards, these dangerous practices are put into place. These practices can eventually lead to the woman developing eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia. As achieving the "beauty ideal" becomes a more popular phenomenon, these eating disorders are becoming more prevalent, especially in young women.[36] Researchers have found that magazine advertisements promoting dieting and thinness are far more prevalent in women's magazine than in men's magazine, and that female television characters are far more likely to be thin than male characters.[37] Eating disorders stem from individual body dysmorphia, or an excessive preoccupation with perceived flaws in appearance.[32] Researchers suggest that this behavior strongly correlates with societal pressure for women to live up to the standards of beauty set by a culture obsessed with being thin.[32] Research has shown that people have subconsciously associated heavier body sizes with negative personality characteristics such as laziness and lack of self-control.[38] Fat-body prejudice appears as young as early childhood and continues into adult years.[38] The problem of negative body-image worsens as females go through puberty; girls in adolescence frequently report being dissatisfied with their weight and fear future weight gain.[39] According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD), the age of the onset of eating disorders is getting younger.[32] Girls as young as elementary-school age report body dissatisfaction and dieting in order to look like magazine models.[38]

Ellen Staurowsky characterized serious psychological and physical health risks associated with girls' negative body images. Negative body image is often associated with disordered eating, depression, and even substance abuse. There is widespread evidence of damaging dissatisfaction among women and young girls with their appearance.[40]

Evolutionary perspectives

Ideas of feminine beauty may have originated from features that correlate with fertility and health.[41] These features include a figure where there is more fat distribution in the hip and thigh area, and vary between different cultures. In both Western and Eastern cultures, having a smaller waist and bigger hips is considered attractive.[42]

Gallery

Venus at a Mirror, Peter Paul Rubens, 1615. In the 17th century fatter bodies were idealized.[43]

Venus at a Mirror, Peter Paul Rubens, 1615. In the 17th century fatter bodies were idealized.[43]

Actress Marilyn Monroe was perceived as the epitome of beauty in the 1950s.[44] Her image has been used to popularize the hourglass figure.

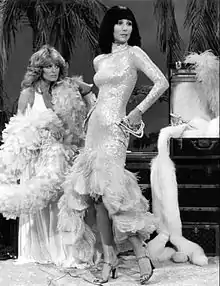

Actress Marilyn Monroe was perceived as the epitome of beauty in the 1950s.[44] Her image has been used to popularize the hourglass figure. Farrah Fawcett and Cher in 1976. From the 1960s up to the 1980s, women aimed to look skinny. Tanned skin also became popular.[43]

Farrah Fawcett and Cher in 1976. From the 1960s up to the 1980s, women aimed to look skinny. Tanned skin also became popular.[43]

References

- Spade, Joan Z; Valentine, Catherine (Kay) G (2010). The Kaleidoscope of Gender: Prisms, Patterns and Possibilities (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1412979061.

- Shaw and Lee, Susan and Janet. Women's Voices Feminist Visions. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Education. p. 189.

- Thesander, Marianne (1997). The Feminine Ideal. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. pp. 20–25. ISBN 978-1861890047.

- "We need to stop chasing unrealistic beauty standards in Asia and start feeling beautiful". CNA Lifestyle.

- "Unrealistic Beauty Standards: Korea's Cosmetic Obsession". Seoulbeats. 26 March 2015.

- Stevenson, Alexandra (23 November 2018). "South Korea Loves Plastic Surgery and Makeup. Some Women Want to Change That". The New York Times.

- Gay, L. l. (2016). GOLD, CRIMSON AND IVORY: THE IDEAL FEMALE BEAUTY AND ITS MATERIAL CULTURE IN 16TH CENTURY ITALY AND FRANCE. Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, (80/81), 35–41.

- "Les standards de beauté féminine de 8 pays décryptés". CNEWS (in French).

- Lentz, Cheyenne. "9 major differences between French and American beauty". Insider.

- "Les nouveaux codes de la beauté". Le Monde.fr (in French). 10 February 2012.

- Makkar, Jalmeen K.; Strube, Michael J. (1995). "Black Women's Self-Perceptions of Attractiveness Following Exposure to White Versus Black Beauty Standards: The Moderating Role of Racial Identity and Self-Esteem". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 25 (17): 1547–1566. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02632.x. ISSN 1559-1816.

- Wilder, JeffriAnne (2015-10-26). Color Stories: Black Women and Colorism in the 21st Century: Black Women and Colorism in the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3110-2.

- Balcetis, E.; Cole, S.; Chelberg, M. B.; Alicke, M. (2013). "Searching out the ideal: Awareness of ideal body standards predicts lower global self-esteem in women". Self and Identity. 12 (1): 99–113. doi:10.1080/15298868.2011.639549. S2CID 143048134.

- Hunter, Margaret (2007). "The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality". Sociology Compass. 1 (1): 237–254. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00006.x. ISSN 1751-9020.

- Berry, D. Channsin; Duke, Bill (2011-09-14), Dark Girls (Documentary), Soren Baker, Ronald Boutelle, Joni Bovill, Kirk Bovill, Duke Media, Urban Winter Entertainment, retrieved 2020-11-02

- Engel, Laura (2018), Jones, Emrys D.; Joule, Victoria (eds.), "Epilogue: Body Double—Katharine Hepburn at Madame Tussauds", Intimacy and Celebrity in Eighteenth-Century Literary Culture: Public Interiors, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 293–298, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76902-8_13, ISBN 978-3-319-76902-8, retrieved 2020-11-02

- Heubeck, Girls and Body Image: Media's Effect, How Parents Can Help. WebMD. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- Dittmar, H.; Halliwell, E.; Ive, S. (2006). "Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls" (PDF). Developmental Psychology. 42 (2): 283–292. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.9493. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. PMID 16569167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-16. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- White, Michele (2009). "Networked bodies and extended corporealities: Theorizing the relationship between the body, embodiment, and contemporary new media". Feminist Studies.

- Kosut, Mary (2012). Encyclopedia of Gender in Media. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, Inc. 2012. pp. 16–17.

- Groesz, L. M.; Levine, M. P.; Murnen, S. K. (2002). "The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 31 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1002/eat.10005. PMID 11835293.

- Swami, Viren; Coles, Rebecca; Wilson, Emma; Salem, Natalie; Wyrozumska, Karolina; Furnham, Adrian (2010). "Oppressive Beliefs at Play: Associations Among Beauty Ideals and Practices and Individual Differences in Sexism, Objectification of Others, and Media Exposure". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 34 (3): 365–379. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01582.x. ISSN 1471-6402. OCLC 985114735. S2CID 143388437.

- "New Dove Research Finds Beauty Pressures Up, and Women and Girls Calling for Change". CISION PR Newswire. PR Newswire. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- "Our Research". Dove. Dove. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- Tiggemann, Marika; Zaccardo, Mia (2016). "'Strong is the new skinny': A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram". Journal of Health Psychology. 23 (8): 1003–1011. doi:10.1177/1359105316639436. ISSN 1359-1053. OCLC 967845901. PMID 27611630. S2CID 5115417.

- Fardouly, Jasmine; Willburger, Brydie K.; Vartanian, Lenny R. (February 2017). "Instagram use and young women's body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways". New Media & Society. 20 (4): 1380–1395. doi:10.1177/1461444817694499. ISSN 1461-4448. OCLC 852641454. S2CID 4953527.

- Caldeira, Sofia P.; De Ridder, Sander (2017). "Representing diverse femininities on Instagram: A case study of the body-positive @effyourbeautystandards Instagram account". Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies. 9 (2): 321–337. doi:10.1386/cjcs.9.2.321_1. ISSN 1757-1898. OCLC 967845901.

- Baker-Sperry, L.; Grauerholz, L. (2003). "The pervasiveness and persistence of the feminine beauty ideal in children's fairy tales". Gender & Society. 17 (5): 711–726. doi:10.1177/0891243203255605. S2CID 54711044.

- Grimm, J. & Grimm, W. (1857). Snow White. Berlin: Children's and Household Tales.

- Towbin, M.A.; Haddock, S.A.; Zimmerman, T.S.; Lund, L.K.; Tanner, L.R. (2004). "Images of gender, race, age, and sexual orientation in Disney feature-length animated films". Journal of Feminist Family Therapy. 15 (4): 19–44. doi:10.1300/j086v15n04_02. ISSN 0895-2833. OCLC 1065271039. S2CID 143306026.

- "Unrealistic anatomies of Disney princesses revealed". NY Daily News. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- Fitts, M. & O’Brien, J. (2009). Body image. In Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. (pp. 82–87). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Renzetti, C. M., Curran, D. J., & Maier, S. L. (2012). Women, men, and society (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Cash, T. F.; Morrow, J. A.; Hrabosky, J. I.; Perry, A. A. (2004). "How has body image changed? A cross-sectional investigation of college women and men from 1983 to 2001" (PDF). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 72 (6): 1081–1089. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.72.6.1081. PMID 15612854.

- Jefferson, D. L.; Stake, J. E. (2009). "Appearance self-attitudes of African American and European American women: Media comparisons and internalization of beauty ideals". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 33 (4): 396–409. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01517.x. S2CID 144320322.

- Mazur, Allen (August 1986). "U.S. Trends in Feminine Beauty and Overadaptation" (PDF). The Journal of Sex Research. 22 (3): 281–303. doi:10.1080/00224498609551309.

- Jackson, L. A. (1992). Physical appearance and gender: Sociobiological and sociocultural perspectives. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Owen, P. R.; Laurel; Seller, E. (2000). "Weight and shape ideals: Thin is dangerously in". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 30 (5): 979–990. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02506.x. ISSN 1559-1816. OCLC 66791717.

- Serdar, K. L. (2011). Female body image and the mass media: Perspectives on how women internalize the ideal beauty standard. Westminster College. Westminster Coll., nd Web.

- "Her Life Depends On It II" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Singh, Devendra; Singh, Dorian (2011). "Shape and Significance of Feminine Beauty: An Evolutionary Perspective". Sex Roles. 64 (9–10): 723–731. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9938-z. S2CID 144644793.

- Singh, D.; Renn, P.; Singh, A. (2007). "Did the perils of abdominal obesity affect depiction of feminine beauty in the sixteenth to eighteenth century British literature? Exploring the health and beauty link". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1611): 891–894. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0239. PMC 2093974. PMID 17251110.

- "A Timeline of Sexy Defined Through the Ages". Discovery News. StyleCaster. March 19, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- "The Ideal Woman Through the Ages: Photos". Discovery News. Discovery Communications. December 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2019.