Mythopoeia

Mythopoeia (also mythopoesis, after Hellenistic Greek μυθοποιία, μυθοποίησις "myth-making") is a narrative genre in modern literature and film where a fictional or artificial mythology is created by the writer of prose or other fiction. This meaning of the word mythopoeia follows its use by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 1930s. The authors in this genre integrate traditional mythological themes and archetypes into fiction.

| Literature |

|---|

|

| Major forms |

| Genres |

| Media |

| Techniques |

| History and lists |

| Discussion |

|

|

Introduction and definition

Mythopoesis is also the act of making (or "producing") mythologies. Notable mythopoeic authors include J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, William Blake, H. P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsany, George R. R. Martin, Mervyn Peake and George MacDonald. While many literary works carry mythic themes, only a few approach the dense self-referentiality and purpose of mythopoesis. It is invented mythology that, rather than rising out of centuries of oral tradition, are penned over a short period of time by a single author or small group of collaborators.

As distinguished from fantasy worlds or fictional universes aimed at the evocation of detailed worlds with well-ordered histories, geographies, and laws of nature, mythopoeia aims at imitating and including real-world mythology, specifically created to bring mythology to modern readers, and/or to add credibility and literary depth to fictional worlds in fantasy or science fiction books and movies.

Such mythologies are almost invariably created entirely by an individual, like the world of Middle-earth.

Etymology

The term mythopoeia is from Greek μυθοποιία 'myth-making'.[1] In early uses, it referred to the making of myths in ancient times.[2] It was adopted and used by Tolkien as a title of one of his poems, written in 1931 and published in Tree and Leaf.[3] The poem popularized the word mythopoeia as a literary and artistic endeavor and genre.

Place in society

Works of mythopoeia are often categorized as fantasy or science fiction but fill a niche for mythology in the modern world, according to Joseph Campbell, a famous student of world mythology. Campbell spoke of a Nietzschean world which has today outlived much of the mythology of the past. He claimed that new myths must be created, but he believed that present culture is changing too rapidly for society to be completely described by any such mythological framework until a later age.

Critics of the genre

Mythopoeia is sometimes called artificial mythology, which emphasizes that it did not evolve naturally and is an artifice comparable with artificial language, so should not be taken seriously as mythology. For example, the noted folklorist Alan Dundes argued that "any novel cannot meet the cultural criteria of myth. A work of art, or artifice, cannot be said to be the narrative of a culture's sacred tradition...[it is] at most, artificial myth."[4]

In literature

Lord Dunsany

Lord Dunsany's book The Gods of Pegana, published in 1905, is a series of short stories linked by Dunsany's invented pantheon of deities who dwell in Pegāna. It was followed by a further collection Time and the Gods and by some stories in The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories and in Tales of Three Hemispheres.

In 1919, Dunsany told an American interviewer, "In The Gods of Pegana I tried to account for the ocean and the moon. I don't know whether anyone else has ever tried that before".[5] Dunsany's work influenced J. R. R. Tolkien's later writings.[6]

J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien wrote a poem titled Mythopoeia following a discussion on the night of 19 September 1931 at Magdalen College, Oxford with C. S. Lewis and Hugo Dyson, in which he intended to explain and defend creative myth-making.[4] The poem refers to the creative human author as "the little maker" wielding his "own small golden sceptre" and ruling his "subcreation" (understood as creation of Man within God's primary creation).

Tolkien's wider legendarium includes not only origin myths, creation myths and an epic poetry cycle, but also fictive linguistics, geology and geography. He more succinctly explores the function of such myth-making, "subcreation" and "Faery" in the short story Leaf by Niggle (1945), the novella Smith of Wootton Major (1967), and the essays Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics (1936) and On Fairy-Stories (1939).

Written in 1939 for presentation by Tolkien at the Andrew Lang lecture at the University of St Andrews and published in print in 1947, On Fairy-Stories explains "Faery" as both a fictitious realm and an archetypal plane in the psyche or soul from whence Man derives his "subcreative" capacity. Tolkien emphasizes the importance of language in the act of channeling "subcreation", speaking of the human linguistic faculty in general as well as the specifics of the language used in a given tradition, particularly in the form of story and song:

Mythology is not a disease at all, though it may like all human things become diseased. You might as well say that thinking is a disease of the mind. It would be more near the truth to say that languages, especially modern European languages, are a disease of mythology. But Language cannot, all the same, be dismissed. The incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are in our world coeval. The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalization and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things (and finding it fair to look upon), but sees that it is green as well as being grass. But how powerful, how stimulating to the very faculty that produced it, was the invention of the adjective: no spell or incantation in Faerie is more potent. And that is not surprising: such incantations might indeed be said to be only another view of adjectives, a part of speech in a mythical grammar. The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter's power—upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes. It does not follow that we shall use that power well upon any plane. We may put a deadly green upon a man’s face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and put hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such "fantasy," as it is called, new form is made; Faerie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator.

Tolkien's mythopoetic observations have been noted for their similarity to the Christian concept of Logos or "The Word", which is said to act as both "the [...] language of nature" spoken into being by God, and "a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM".[7][8]

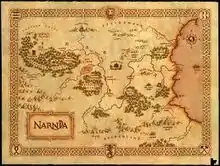

C. S. Lewis

At the time that Tolkien debated the usefulness of myth and mythopoeia with C. S. Lewis in 1931, Lewis was a theist[9] and liked but was skeptical of mythology, taking the position that myths were "lies and therefore worthless, even though 'breathed through silver'".[4][10] However Lewis later began to speak of Christianity as the one "true myth". Lewis wrote, "The story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened."[11] Subsequently, his Chronicles of Narnia is regarded as mythopoeia, with storylines referencing that Christian mythology, namely the narrative of a great king who is sacrificed to save his people and is resurrected.

Lewis's mythopoeic intent is often confused with allegory, where the characters and world of Narnia would stand in direct equivalence with concepts and events from Christian theology and history, but Lewis repeatedly emphasized that an allegorical reading misses the point (the mythopoeia) of the Narnia stories.[12] He shares this skepticism toward allegory with Tolkien, who disliked "conscious and intentional" allegory as it stood in opposition the broad and "inevitable" allegory of themes like "Fall" and "Mortality".[13]

C. S. Lewis also created a mythopoeia in his neo-medieval representation of extra-planetary travel and planetary "bodies" in the Cosmic or Space Trilogy.

William Blake

William Blake's "prophetic works" (e.g. Vala, or The Four Zoas) contain a rich panoply of original gods, such as Urizen, Orc, Los, Albion, Rintrah, Ahania and Enitharmon. Blake was an important influence on Aleister Crowley's Thelemic writings, whose dazzling pantheon of 'Godforms' and radically re-cast figures from Egyptian mythology and the Book of Revelation constitute an allegorical mythology of their own.

Collaborative efforts

Current attempts to produce a new mythology through collaborative means include the movement known as New or Metamodern Classicism. According to its website, metamodern classicism seeks to create "a vast, collaborative cultural project, uniting Painters, Poets, Musicians, Architects, and all Artists in one mythopoeic endeavor. Our goal is none other than a living mythological tradition: interactive, dynamic, evolving—and relevant."[16]

The Cthulhu Mythos of H. P. Lovecraft was likewise taken up by numerous collaborators and admirers.

Other modern literature

Stories by George MacDonald and H. Rider Haggard are in this category. C. S. Lewis praised both for their "mythopoeic" gifts.[17]

T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922) was a deliberate attempt to model a 20th-century mythology patterned after the birth-rebirth motif described by Frazer.[18]

The repeated motifs of Jorge Luis Borges's fictional works (mirrors, labyrinths, tigers, etc.) tantalizingly hint at a deeper underlying mythos and yet stealthily hold back from any overt presentation of it.

The pulp works of Edgar Rice Burroughs (from 1912) and Robert E. Howard (from 1924) contain imagined worlds vast enough to be universes in themselves, as did the science fiction of E. E. "Doc" Smith, Frank Herbert, and Michael Moorcock one or two generations later.

Fritz Leiber (from the 1930s) also created a vast world, similar to that of Robert E. Howard's; vast enough to be a universe, and indeed was a fictional omniverse. It is stated that the two main protagonists, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser "travelled through universes and lands" and eventually going on to say they ended up back in the fictional city of Lankhmar.

Star Maker (1937) by Olaf Stapledon is a rare attempt at a cohesive science fiction mythos.

In the 1960s through the 1990s, Roger Zelazny authored many mythopoetic novels, such as Lord of Light. Zelazny's Chronicles of Amber is a ten-volume series of particular note for its mythic and metaphysical themes. Zelazny cited the World of Tiers series by Philip Jose Farmer as an influence.[19]

Greg Stafford created the world and attendant mythology of Glorantha (from 1975), which formed the basis for a role-playing game (see Runequest and Heroquest), though its literary scope far exceeds its genre.

Stephen King's novels and short stories form an intricate and highly developed mythos, drawing in part on the Lovecraftian, with characters such as the demonic Crimson King and Randall Flagg appearing in several (otherwise unrelated) works, as well as a supernatural force known only as "The White". The Dark Tower series serves as a linchpin for this mythos, connecting with practically all of King's various storylines in one way or another.

J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter book series, as well as the series of films adapted from her work, exist within a mythopoetic universe Rowling created by combining elements from various mythologies with her own original fantasy.

Rick Riordan's Camp Half-Blood chronicles, which include three pentological book series, Percy Jackson & the Olympians, The Heroes of Olympus and The Trials of Apollo series, as well as their film adaptations, exist within a mythopoetic recreation of the ancient Greek and Roman mythologies and chronicles the lives of modern American-born, Graeco-Roman demigods and their interactions with Gods. His other mythopoetic works, The Kane Chronicles and Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard are also similar except the fact that they revolve around Egyptian and Norse mythologies. Riordan's works amalgamate elements of day-to-day life of teenagers like coming of age, ADHD, love and teenage angst into modern interpretations of Egyptian and Graeco-Roman mythologies and his own fantasy.

The novels of Neil Gaiman, especially Neverwhere, American Gods and Anansi Boys, function similarly.

Philip Pullman created an alternate version of the Judeo-Christian mythology in His Dark Materials, and its sequel series The Book of Dust, where the Angels have more or less created a facade to fool the mortals.

Indian author Amish Tripathi's Shiva trilogy and its prequel series, Ram Chandra series chronicle the life and exploits of Hindu Gods, Shiva and Rama recast as Great, historical human figures. It carefully blends traditional Indian characters into a mythopoetic recreation of the original tale.[20] In India, this trend of "myth retelling" was initiated by classic South Indian novelist, M. T. Vasudevan Nair, whose Malayalam language classic, Randamoozham, and its many translations (including "The Lone Warrior" in English) follow a similar pattern of plot-crafting. Other works like Shivaji Sawant's Mrityunjaya and Yugandhar, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni's The Palace of Illusions, Anand Neelakantan's Asura: Tale of the Vanquished, Ashok Banker and Devdutt Pattanaik's various retellings and Krishna Udayasankar's Aryavarta Chronicles have also followed this lead.

Modern usage

Frank McConnell, author of Storytelling and Mythmaking and professor of English, University of California, stated film is another "mythmaking" art, stating: "Film and literature matter as much as they do because they are versions of mythmaking."[21] He also thinks film is a perfect vehicle for mythmaking: "FILM...strives toward the fulfillment of its own projected reality in an ideally associative, personal world."[22] In a broad analysis, McConnell associates the American western movies and romance movies to the Arthurian mythology,[23] adventure and action movies to the "epic world" mythologies of founding societies,[24] and many romance movies where the hero is allegorically playing the role of a knight, to "quest" mythologies like Sir Gawain and the Quest for the Holy Grail.[25]

Filmmaker George Lucas speaks of the cinematic storyline of Star Wars as an example of modern myth-making. In 1999 he told Bill Moyers, "With Star Wars I consciously set about to re-create myths and the classic mythological motifs."[26] The idea of Star Wars as "mythological" has been met with mixed reviews. On the one hand, Frank McConnell says "it has passed, quicker than anyone could have imagined, from the status of film to that of legitimate and deeply embedded popular mythology."[27] John Lyden, the Professor and Chair of the Religion Department at Dana College, argues that Star Wars does indeed reproduce religious and mythical themes; specifically, he argues that the work is apocalyptic in concept and scope.[28] Steven D. Greydanus of The Decent Film Guide agrees, calling Star Wars a "work of epic mythopoeia".[29] In fact, Greydanus argues that Star Wars is the primary example of American mythopoeia:

"The Force, the Jedi knights, Darth Vader, Obi-Wan, Princess Leia, Yoda, lightsabers, and the Death Star hold a place in the collective imagination of countless Americans that can only be described as mythic. In my review of A New Hope I called Star Wars 'the quintessential American mythology,' an American take on King Arthur, Tolkien, and the samurai/wuxia epics of the East ..."[29]

Roger Ebert has observed regarding Star Wars, "It is not by accident that George Lucas worked with Joseph Campbell, an expert on the world's basic myths, in fashioning a screenplay that owes much to man's oldest stories."[30] The "mythical" aspects of the Star Wars franchise have been challenged by other film critics. Regarding claims by Lucas himself, Steven Hart observes that Lucas didn't mention Joseph Campbell at the time of the original Star Wars; evidently they met only in the 1980s. Their mutual admiration "did wonders for [Campbell's] visibility" and obscured the tracks of Lucas in the "despised genre" science fiction; "the epics make for an infinitely classier set of influences".[31]

In The Mythos of the Superheroes and the Mythos of the Saints,[32] Thomas Roberts observes that:

"To the student of myth, the mythos of the comics superheroes is of unique interest."

"Why do human beings want myths and how do they make them? Some of the answers to those questions can be found only sixty years back. Where did Superman and the other superheroes come from? In his Encyclopedia of the Superheroes, Jeff Rovin correctly observes, "In the earliest days, we called them 'gods'."

Superman, for example, sent from the "heavens" by his father to save humanity, is a messiah-type of character in the Biblical tradition.[33] Furthermore, along with the rest of DC Comic's Justice League of America, Superman watches over humanity from the Watchtower in the skies; just like the Greek gods do from Mount Olympus.[34] "Jack Kirby's Fourth World" series, with the cosmic struggle between Darkseid's Apokolips and the gods of New Genesis and Mister Miracle and Orion as messiah-figures is another good example. Neil Gaiman's Sandman series created a mythology around the Endless, a family of god-like embodiments of natural forces like death and dreaming.

In music

In classical music, Richard Wagner's operas were a deliberate attempt to create a new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"), transforming the legends of the Teutonic past nearly out of recognition into a new monument to the Romantic project.

In popular music, George Clinton's Parliament-Funkadelic collective produced numerous concept albums which tied together in what is referred to as P-Funk mythology.

While ostensibly known for improvised jamming, the rock group Phish first cemented as a group while producing leading member Trey Anastasio's senior project in college, called The Man Who Stepped into Yesterday. The song cycle features narration of major events in a mythical land called Gamehendge, containing types of imaginary creatures and primarily populated by a race called the "Lizards". It is essentially a postmodern pastiche, drawing from Anastasio's interest in musicals or rock operas as much as from reading philosophy and fiction.[35] The creation of the myth is considered by many fans the thesis statement of the group, musically and philosophically, as Gamehendge's book of lost secrets (called the "Helping Friendly Book") is summarized as an encouragement to improvisation in any part of life: "the trick was to surrender to the flow."[36]

2112 by the Canadian band Rush is a song cycle about a young man in a future, oppressive society discovering an ancient guitar- and thereby his own free expression- only to have his instrument and his new found freedoms crushed by the rulers of his society.

The musical collective NewVillager constructed a mythology from Joseph Campell's Monomyth of which all their music, art, and videos serve to express.

The band Rhapsody of Fire have created and tell the stories of a full-developed fantasy world with tales of epic wars between good and evil, although many elements are taken directly from Tolkien and other authors.

The black metal band Immortal's lyricist Harald Nævdal has created a mythological realm called Blashyrkh – described by the band as a northern "Frostdemon" realm[37] – filled with demons, battles, winter landscapes, woods, and darkness which is the primary subject on their albums. A mythology forming a greater whole that has been in development from the start of their career in 1991.

Organizations

The Mythopoeic Society exists to promote mythopoeic literature, partly by way of the Mythopoeic Awards.

See also

- Campaign setting

- Constructed world

- Fantasy world

- Fictional universe

- Legendarium

- Mythic fiction, literature that is rooted in tropes and themes of existing – instead of more artificial – mythology

- Religion and mythology / List of religious ideas in fantasy fiction

- Archetype

References

- New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- For example, "The first two, the most remote stages, are purely linguistic germs of mythology: the third is in the domain of mythopoeia, or myth-building." Bunsen, C. C. J. (1860). Egypt's Place in Universal History: an Historical Investigation in Five Books, Volume IV. Translated by Charles H. Cottrell. Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. p. 450. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "Mythopoeia by J.R.R. Tolkien". ccil.org. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006.

- Dundes, quoted by Adcox, 2003.

- M. K. Wisehart, "Ideals and Fame: A One-Act Conversation With Lord Dunsany," New York Sun Book World, 19 October 1919, p.25

- Dilworth, Dianna (18 August 2011). "What Did J.R.R. Tolkien Read?". GalleyCat. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Coutras, Lisa (3 August 2016). Tolkien's Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle-earth. Springer. pp. 92–94. ISBN 9781137553454.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2002). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World. Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873387446.

- (Lewis 1946, pp. 66–67)

- Menion, 2003/2004 citing essays by Tolkien using the words "fundamental things".

- Brown, Dave. "Real Joy and True Myth". Geocities.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- Abate, Michelle Ann; Weldy, Lance (2012). C.S. Lewis. London: Palgrave. p. 131. ISBN 9781137284976.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (21 February 2014). The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780544363793.

- "Copy Information for Jerusalem The Emanation of The Giant Albion". William Blake Archive. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Object description for "Jerusalem The Emanation of The Giant Albion, copy E, object 15 (Bentley 15, Erdman 15, Keynes 15)"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Metamodern Classicism". weebly.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Lobdell, 2004.

- Oser, Lee (Winter 1996). "Eliot, Frazer, and the Mythology of Modernism". The Southern Review. 32:1: 183 – via ProQuest.

- "...And Call Me Roger": The Literary Life of Roger Zelazny, Part 2, by Christopher S. Kovacs. In: The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny, Volume 2: Power & Light, NESFA Press, 2009.

- Tripathi, Amish. "Shiva-Trilogy". authoramish.com. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- McConnell 1979:6

- McConnell 1979:5, 99: "film is a perfect model of the epic paradigm: the founder of the land, the man who walls in and defines the human space of a given culture..."

- McConnell 1979:15.

- McConnell 1979:21.

- McConnell 1979:13, 83–93.

- Hart, 2002. Evidently quoting Moyers quoting Lucas in Time, 26 April 1999.

- McConnell, 1979:18.

- Lyden, 2000.

- Greydanus 2000–2006.

- Hart, 2002. Quoting Ebert on Star Wars in his series The Great Movies.

- Hart 2002.

- Roberts, Thomas, The Mythos of the Superheroes and the Mythos of the Saints

- KNOWLES, Christopher, Our Gods Wear Spandex, Weiser, pp. 120–2

- International Journal of Comic Art, University of Michigan, pp. 280

- Puterbaugh, Parke. Phish: The Biography. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 65–67. Print.

- "Phish.Net: The Lizards Lyrics". phish.net.

- "CoC : Immortal : Interview : 5/19/1999". Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Inklings

Tolkien:

- Adcox, John. Can Fantasy be Myth? Mythopoeia and The Lord of the Rings. Published by The Newsletter of the Mythic Imagination Institute, September/October, 2003.

- Menion, Michael. Tolkien Elves and Art, in J. R. R. Tolkien's Aesthetics. 2003/2004 (commentary on Mythopoeia the poem).

- Chance, Jane (April 2004). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

C. S. Lewis, George MacDonald:

- Lobdell, Jared (1 July 2004). The Scientifiction Novels of C.S. Lewis: Space and Time in the Ransom Stories. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 0-7864-8386-5.

- Lewis, C. S. (1946), The Great Divorce, London: Collins, 0-00-628056-0

- Film-making as myth-making

- McConnell, Frank D. (1982). Storytelling and Mythmaking: Images from Film and Literature. ISBN 978-0-19-503210-9.

Lucas:

- Hart, Steven. Galactic gasbag, Salon.com', April, 2002.

- Greydanus, Steven D. An American Mythology: Why Star Wars Still Matters, Decent Film Guide, copyright 2000–2006.

- Lyden, John. The Apocalyptic Cosmology of Star Wars, The Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 4, No. 1 April 2000 (Abstract).

External links

- Mythopoeia

- Mythopoeia TV tropes