Formal language

In mathematics, computer science, and linguistics, a formal language consists of words whose letters are taken from an alphabet and are well-formed according to a specific set of rules.

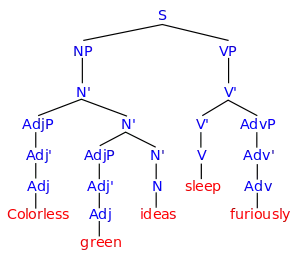

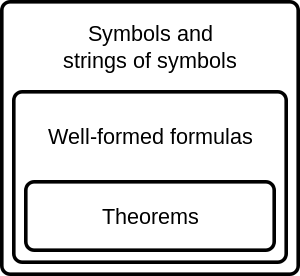

The alphabet of a formal language consists of symbols, letters, or tokens that concatenate into strings of the language.[1] Each string concatenated from symbols of this alphabet is called a word, and the words that belong to a particular formal language are sometimes called well-formed words or well-formed formulas. A formal language is often defined by means of a formal grammar such as a regular grammar or context-free grammar, which consists of its formation rules.

The field of formal language theory studies primarily the purely syntactical aspects of such languages—that is, their internal structural patterns. Formal language theory sprang out of linguistics, as a way of understanding the syntactic regularities of natural languages. In computer science, formal languages are used among others as the basis for defining the grammar of programming languages and formalized versions of subsets of natural languages in which the words of the language represent concepts that are associated with particular meanings or semantics. In computational complexity theory, decision problems are typically defined as formal languages, and complexity classes are defined as the sets of the formal languages that can be parsed by machines with limited computational power. In logic and the foundations of mathematics, formal languages are used to represent the syntax of axiomatic systems, and mathematical formalism is the philosophy that all of mathematics can be reduced to the syntactic manipulation of formal languages in this way.

History

The first formal language is thought to be the one used by Gottlob Frege in his Begriffsschrift (1879), literally meaning "concept writing", and which Frege described as a "formal language of pure thought."[2]

Axel Thue's early semi-Thue system, which can be used for rewriting strings, was influential on formal grammars.

Words over an alphabet

An alphabet, in the context of formal languages, can be any set, although it often makes sense to use an alphabet in the usual sense of the word, or more generally a character set such as ASCII or Unicode. The elements of an alphabet are called its letters. An alphabet may contain an infinite number of elements;[note 1] however, most definitions in formal language theory specify alphabets with a finite number of elements, and most results apply only to them.

A word over an alphabet can be any finite sequence (i.e., string) of letters. The set of all words over an alphabet Σ is usually denoted by Σ* (using the Kleene star). The length of a word is the number of letters it is composed of. For any alphabet, there is only one word of length 0, the empty word, which is often denoted by e, ε, λ or even Λ. By concatenation one can combine two words to form a new word, whose length is the sum of the lengths of the original words. The result of concatenating a word with the empty word is the original word.

In some applications, especially in logic, the alphabet is also known as the vocabulary and words are known as formulas or sentences; this breaks the letter/word metaphor and replaces it by a word/sentence metaphor.

Definition

A formal language L over an alphabet Σ is a subset of Σ*, that is, a set of words over that alphabet. Sometimes the sets of words are grouped into expressions, whereas rules and constraints may be formulated for the creation of 'well-formed expressions'.

In computer science and mathematics, which do not usually deal with natural languages, the adjective "formal" is often omitted as redundant.

While formal language theory usually concerns itself with formal languages that are described by some syntactical rules, the actual definition of the concept "formal language" is only as above: a (possibly infinite) set of finite-length strings composed from a given alphabet, no more and no less. In practice, there are many languages that can be described by rules, such as regular languages or context-free languages. The notion of a formal grammar may be closer to the intuitive concept of a "language," one described by syntactic rules. By an abuse of the definition, a particular formal language is often thought of as being equipped with a formal grammar that describes it.

Examples

The following rules describe a formal language L over the alphabet Σ = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, +, =}:

- Every nonempty string that does not contain "+" or "=" and does not start with "0" is in L.

- The string "0" is in L.

- A string containing "=" is in L if and only if there is exactly one "=", and it separates two valid strings of L.

- A string containing "+" but not "=" is in L if and only if every "+" in the string separates two valid strings of L.

- No string is in L other than those implied by the previous rules.

Under these rules, the string "23+4=555" is in L, but the string "=234=+" is not. This formal language expresses natural numbers, well-formed additions, and well-formed addition equalities, but it expresses only what they look like (their syntax), not what they mean (semantics). For instance, nowhere in these rules is there any indication that "0" means the number zero, "+" means addition, "23+4=555" is false, etc.

Constructions

For finite languages, one can explicitly enumerate all well-formed words. For example, we can describe a language L as just L = {a, b, ab, cba}. The degenerate case of this construction is the empty language, which contains no words at all (L = ∅).

However, even over a finite (non-empty) alphabet such as Σ = {a, b} there are an infinite number of finite-length words that can potentially be expressed: "a", "abb", "ababba", "aaababbbbaab", .... Therefore, formal languages are typically infinite, and describing an infinite formal language is not as simple as writing L = {a, b, ab, cba}. Here are some examples of formal languages:

- L = Σ*, the set of all words over Σ;

- L = {a}* = {an}, where n ranges over the natural numbers and "an" means "a" repeated n times (this is the set of words consisting only of the symbol "a");

- the set of syntactically correct programs in a given programming language (the syntax of which is usually defined by a context-free grammar);

- the set of inputs upon which a certain Turing machine halts; or

- the set of maximal strings of alphanumeric ASCII characters on this line, i.e.,

the set {the, set, of, maximal, strings, alphanumeric, ASCII, characters, on, this, line, i, e}.

Language-specification formalisms

Formal languages are used as tools in multiple disciplines. However, formal language theory rarely concerns itself with particular languages (except as examples), but is mainly concerned with the study of various types of formalisms to describe languages. For instance, a language can be given as

- those strings generated by some formal grammar;

- those strings described or matched by a particular regular expression;

- those strings accepted by some automaton, such as a Turing machine or finite-state automaton;

- those strings for which some decision procedure (an algorithm that asks a sequence of related YES/NO questions) produces the answer YES.

Typical questions asked about such formalisms include:

- What is their expressive power? (Can formalism X describe every language that formalism Y can describe? Can it describe other languages?)

- What is their recognizability? (How difficult is it to decide whether a given word belongs to a language described by formalism X?)

- What is their comparability? (How difficult is it to decide whether two languages, one described in formalism X and one in formalism Y, or in X again, are actually the same language?).

Surprisingly often, the answer to these decision problems is "it cannot be done at all", or "it is extremely expensive" (with a characterization of how expensive). Therefore, formal language theory is a major application area of computability theory and complexity theory. Formal languages may be classified in the Chomsky hierarchy based on the expressive power of their generative grammar as well as the complexity of their recognizing automaton. Context-free grammars and regular grammars provide a good compromise between expressivity and ease of parsing, and are widely used in practical applications.

Operations on languages

Certain operations on languages are common. This includes the standard set operations, such as union, intersection, and complement. Another class of operation is the element-wise application of string operations.

Examples: suppose and are languages over some common alphabet .

- The concatenation consists of all strings of the form where is a string from and is a string from .

- The intersection of and consists of all strings that are contained in both languages

- The complement of with respect to consists of all strings over that are not in .

- The Kleene star: the language consisting of all words that are concatenations of zero or more words in the original language;

- Reversal:

- Let ε be the empty word, then , and

- for each non-empty word (where are elements of some alphabet), let ,

- then for a formal language , .

- String homomorphism

Such string operations are used to investigate closure properties of classes of languages. A class of languages is closed under a particular operation when the operation, applied to languages in the class, always produces a language in the same class again. For instance, the context-free languages are known to be closed under union, concatenation, and intersection with regular languages, but not closed under intersection or complement. The theory of trios and abstract families of languages studies the most common closure properties of language families in their own right.[3]

Closure properties of language families ( Op where both and are in the language family given by the column). After Hopcroft and Ullman. Operation Regular DCFL CFL IND CSL recursive RE Union Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Intersection Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes Complement Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No Concatenation Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Kleene star Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes (String) homomorphism Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes ε-free (string) homomorphism Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Substitution Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Inverse homomorphism Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Reverse Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Intersection with a regular language Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Applications

Programming languages

A compiler usually has two distinct components. A lexical analyzer, sometimes generated by a tool like lex, identifies the tokens of the programming language grammar, e.g. identifiers or keywords, numeric and string literals, punctuation and operator symbols, which are themselves specified by a simpler formal language, usually by means of regular expressions. At the most basic conceptual level, a parser, sometimes generated by a parser generator like yacc, attempts to decide if the source program is syntactically valid, that is if it is well formed with respect to the programming language grammar for which the compiler was built.

Of course, compilers do more than just parse the source code – they usually translate it into some executable format. Because of this, a parser usually outputs more than a yes/no answer, typically an abstract syntax tree. This is used by subsequent stages of the compiler to eventually generate an executable containing machine code that runs directly on the hardware, or some intermediate code that requires a virtual machine to execute.

Formal theories, systems, and proofs

In mathematical logic, a formal theory is a set of sentences expressed in a formal language.

A formal system (also called a logical calculus, or a logical system) consists of a formal language together with a deductive apparatus (also called a deductive system). The deductive apparatus may consist of a set of transformation rules, which may be interpreted as valid rules of inference, or a set of axioms, or have both. A formal system is used to derive one expression from one or more other expressions. Although a formal language can be identified with its formulas, a formal system cannot be likewise identified by its theorems. Two formal systems and may have all the same theorems and yet differ in some significant proof-theoretic way (a formula A may be a syntactic consequence of a formula B in one but not another for instance).

A formal proof or derivation is a finite sequence of well-formed formulas (which may be interpreted as sentences, or propositions) each of which is an axiom or follows from the preceding formulas in the sequence by a rule of inference. The last sentence in the sequence is a theorem of a formal system. Formal proofs are useful because their theorems can be interpreted as true propositions.

Interpretations and models

Formal languages are entirely syntactic in nature but may be given semantics that give meaning to the elements of the language. For instance, in mathematical logic, the set of possible formulas of a particular logic is a formal language, and an interpretation assigns a meaning to each of the formulas—usually, a truth value.

The study of interpretations of formal languages is called formal semantics. In mathematical logic, this is often done in terms of model theory. In model theory, the terms that occur in a formula are interpreted as objects within mathematical structures, and fixed compositional interpretation rules determine how the truth value of the formula can be derived from the interpretation of its terms; a model for a formula is an interpretation of terms such that the formula becomes true.

See also

Notes

- For example, first-order logic is often expressed using an alphabet that, besides symbols such as ∧, ¬, ∀ and parentheses, contains infinitely many elements x0, x1, x2, … that play the role of variables.

References

Citations

- See e.g. Reghizzi, Stefano Crespi (2009), Formal Languages and Compilation, Texts in Computer Science, Springer, p. 8, ISBN 9781848820500,

An alphabet is a finite set

. - Martin Davis (1995). "Influences of Mathematical Logic on Computer Science". In Rolf Herken (ed.). The universal Turing machine: a half-century survey. Springer. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-211-82637-9.

- Hopcroft & Ullman (1979), Chapter 11: Closure properties of families of languages.

Sources

- Works cited

- John E. Hopcroft and Jeffrey D. Ullman, Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading Massachusetts, 1979. ISBN 81-7808-347-7.

- General references

- A. G. Hamilton, Logic for Mathematicians, Cambridge University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-521-21838-1.

- Seymour Ginsburg, Algebraic and automata theoretic properties of formal languages, North-Holland, 1975, ISBN 0-7204-2506-9.

- Michael A. Harrison, Introduction to Formal Language Theory, Addison-Wesley, 1978.

- Rautenberg, Wolfgang (2010). A Concise Introduction to Mathematical Logic (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1221-3. ISBN 978-1-4419-1220-6..

- Grzegorz Rozenberg, Arto Salomaa, Handbook of Formal Languages: Volume I-III, Springer, 1997, ISBN 3-540-61486-9.

- Patrick Suppes, Introduction to Logic, D. Van Nostrand, 1957, ISBN 0-442-08072-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Formal languages. |

- "Formal language", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- University of Maryland, Formal Language Definitions

- James Power, "Notes on Formal Language Theory and Parsing", 29 November 2002.

- Drafts of some chapters in the "Handbook of Formal Language Theory", Vol. 1–3, G. Rozenberg and A. Salomaa (eds.), Springer Verlag, (1997):

- Alexandru Mateescu and Arto Salomaa, "Preface" in Vol.1, pp. v–viii, and "Formal Languages: An Introduction and a Synopsis", Chapter 1 in Vol. 1, pp.1–39

- Sheng Yu, "Regular Languages", Chapter 2 in Vol. 1

- Jean-Michel Autebert, Jean Berstel, Luc Boasson, "Context-Free Languages and Push-Down Automata", Chapter 3 in Vol. 1

- Christian Choffrut and Juhani Karhumäki, "Combinatorics of Words", Chapter 6 in Vol. 1

- Tero Harju and Juhani Karhumäki, "Morphisms", Chapter 7 in Vol. 1, pp. 439–510

- Jean-Eric Pin, "Syntactic semigroups", Chapter 10 in Vol. 1, pp. 679–746

- M. Crochemore and C. Hancart, "Automata for matching patterns", Chapter 9 in Vol. 2

- Dora Giammarresi, Antonio Restivo, "Two-dimensional Languages", Chapter 4 in Vol. 3, pp. 215–267