Fort Mills

Fort Mills (Corregidor, the Philippines) was the location of US Major General George F. Moore's headquarters for the Philippine Department's Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays in early World War II, and was the largest seacoast fort in the Philippines.[2][3] Most of this Coast Artillery Corps fort was built 1904–1910 by the United States Army Corps of Engineers as part of the Taft program of seacoast defense. The fort was named for Brigadier General Samuel Meyers Mills Jr., Chief of Artillery 1905–1906.[4] It was the primary location of the Battle of Corregidor in the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in 1941–42, and of the recapture of Corregidor in February 1945, both in World War II.[5]

| Fort Mills | |

|---|---|

Corregidor Island, Philippines | |

| Part of Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays | |

Corregidor/Fort Mills with other forts inset | |

.svg.png.webp) Fort Mills Location in the Philippines | |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States |

| Site history | |

| Built | completed 1910 |

| Built by | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Col. Paul D. Bunker |

| Garrison |

|

.jpg.webp)

Overview

The United States acquired the Philippines as a territory as a result of the Spanish–American War in 1898. The Taft board of 1905 recommended extensive, then-modern fortifications at the entrance to Manila Bay. The islands there had been declared military reservations on 11 April 1902. Construction soon started and the forts were substantially complete by 1915 as the Coast Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays (renamed Harbor Defenses in 1925).[6] All of them were on islands at the mouth of the bay, except Fort Wint on Grande Island in Subic Bay. As the only large island of these, Corregidor had more gun batteries than the others, along with barracks, other garrison buildings, and facilities for controlling two underwater minefields. Corregidor also had 13 miles of electric railway, an unusual feature in US forts.[7] The forts were designed for one purpose: to prevent enemy surface vessels from entering Manila Bay or Subic Bay. They were designed before airplanes became important in war, and (except for Fort Drum) were vulnerable to air and high-angle artillery attack, being protected only by camouflage. Except for the mortar batteries, the turrets of Fort Drum, and the two 12-inch (305 mm) guns of the 1920s Batteries Smith and Hearn, the forts' guns had restricted arcs of fire of about 170°, and could only bear on targets entering the bay from the west.[5]

Construction

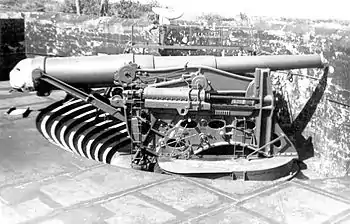

The initial construction on Fort Mills was largely complete by 1911 except three 3-inch gun batteries. The initial gun batteries were:[8]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Way | 4 | 12-inch (305 mm) mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1910-1942 |

| Geary | 8 | 4 12-inch (305 mm) mortar M1890,[9] 4 12-inch (305 mm) mortar M1908 | barbette M1896, M1908 | 1910-1942 |

| Cheney | 2 | 12-inch (305 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1901 | 1910-1942 |

| Wheeler | 2 | 12-inch (305 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1901 | 1910-1942 |

| Crockett | 2 | 12-inch (305 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1901 | 1910-1942 |

| Grubbs | 2 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1895 | disappearing M1901 | 1910-1942 |

| Morrison | 2 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun M1905 | disappearing M1905 | 1910-1942 |

| Ramsey | 3 | 6-inch (152 mm) gun M1905 | disappearing M1905 | 1911-1942 |

| James | 4 | 3-inch (76 mm) gun M1903 | pedestal M1903 | 1910-1942 |

Three additional batteries of two 3-inch (76 mm) guns each followed within a few years; Battery Keyes in 1913 and Batteries Cushing and Hanna in 1919. The 3-inch "mine defense" guns were intended to prevent enemy minesweepers from clearing paths through underwater minefields.[10]

The last new armament at Fort Mills until 1940 was significant but small in quantity: Batteries Smith and Hearn, completed in 1921. These had one 12-inch (305 mm) M1895 gun each on an M1917 long-range carriage, with an elevation of 35° and 360° of traverse, with range increased from 18,400 yd (16,800 m) on a disappearing carriage to 29,300 yd (26,800 m).[11][12] The disadvantage was that the guns were completely unprotected. This type of battery was also built at eight other harbor defense commands in CONUS, Hawaii, and Panama.[13] In 1923 the Washington Naval Treaty prohibited additional fortifications in the Pacific, thus the Philippine forts received no further weapons until after 1936, when Japan withdrew from the treaty, rendering it void.[14] Ironically, had these batteries been modernized, they would have been casemated, restricting them to a 180° field of fire, and would have been less useful against the Japanese on Bataan. One result of the Washington Naval Treaty was the diversion of twelve 240 mm howitzers on a ship bound for the Philippines to Hawaii, where they were placed on fixed mountings on Oahu. The total lack of mobile high-angle artillery was a major impediment to the defense of the Philippines.[15]

Spare gun barrels were provided near some batteries, including Smith and Hearn, due to the inability to re-line used barrels except at specialized facilities in the continental United States (CONUS).[8]

Battery names

The name sources for the batteries at Fort Mills were:[16]

|

Minefields

Manila Bay and Subic Bay had Army-operated minefields as well as naval mines. These minefields were designed to stop all vessels except submarines and shallow-draft surface craft. In Manila Bay, two controlled minefields were placed, one extending west from Corregidor to La Monja Island, and the other extending north from Corregidor to the Bataan Peninsula east of Mariveles Bay. Both of these were operated from Corregidor. Also, in mid-1941 US Navy minefields of contact mines were laid between Mariveles Bay and La Monja Island, and between Corregidor and Carabao Islands, to close off the bay approaches not covered by Army mines.[10][2][17]

On the night of 16–17 December 1941 the passenger ship SS Corregidor (formerly HMS Engadine) hit a mine and sank near Corregidor Island. The ship departed Manila that night without obtaining permission from the US Navy's Inshore Patrol, which meant the minefield operators were not alerted that a friendly ship was departing the harbor. The minefield's usual state in wartime was active, which meant they would detonate on contact. This probably applied to the mines in the designated ship channel as well. When the ship was spotted, some accounts state that Colonel Paul Bunker, commander of the Seaward Defenses, ordered that the minefield remain active. Due to wartime conditions, no official investigation was ever conducted, leaving many questions open. The location at which the ship sank has not been determined, for example.[18] Accounts state that US Army officers informally told Filipino reporters that the mines were placed in safe mode immediately after the sinking. The ship was crowded with 1,200 to 1,500 persons, mostly Filipino civilians evacuating to Mindanao. 150 Philippine Army personnel and seven Americans were on board, along with several 2.95-inch mountain guns badly needed by the forces in the southern Philippines. Three PT boats (PT-32, PT-34 and PT-35) picked up 282 survivors, of which seven later died.[17][19][20][21]

The Malinta Tunnel

The main part of the Malinta Tunnel complex was built on Corregidor from 1932 to 1934, with construction continuing until the Philippines were invaded in December 1941. Most US forts of this era had only small underground facilities, and this tunnel complex was the largest in the US coastal defense system. Due to the Washington Naval Treaty's prohibition on new fortifications, most of the complex was built without appropriated funds, using Filipino convict labor for unskilled tasks, and explosives slated for disposal. During the siege, the Malinta Tunnel proved important to the survival of the Philippine government, the military high command, the medical staff, and numerous civilians.[22]

Japanese conquest of the Philippines

Prelude

From the late 1930s through the surrender in 1942 a number of batteries for 155 mm (6.1 in) GPF guns[23] were built at Fort Mills. These were mobile field guns adopted by the Coast Artillery Corps for use in "tractor-drawn" units, such as the 92nd Coast Artillery. At least a few of these were delivered to the Philippines in 1921 with transfer of the 59th Coast Artillery to the islands.[24] Nine batteries with emplacements for 22 guns were built.[3][8] The US Army's official history states that 19 of these weapons were on Corregidor during the final battle in 1942. Most of these batteries simply had "Panama mounts", circular concrete platforms to stabilize the gun on its mobile carriage. One battery was exceptional, Battery Monja in the southwest part of Corregidor, with two emplacements. One or both of these were casemated by being built into a rock face; this proved to be crucial to the battery remaining in action during the siege. By December 1941 there were seven antiaircraft batteries totaling 28 3-inch guns on Corregidor (including one nearby on Bataan), some manned by the 60th Coast Artillery (AA) and some manned by batteries of the harbor defense regiments.[25][26]

On 26 July 1941 Lieutenant General[27] Douglas MacArthur was recalled to active duty and made the commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), which included the Philippine Scouts and the Philippine Commonwealth Army. MacArthur had been an official U.S. advisor to the Philippine forces as a Philippine Field Marshal from 1935 to 1937, and had continued this function as a civilian since his retirement from the U.S. Army at the end of that period.[28]

The siege begins

The Japanese invaded northern Luzon a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 that brought the US into the war. They advanced rapidly, with other landings elsewhere, notably at Legazpi in southeast Luzon on 12 December, Davao on Mindanao on 20 December, and Lingayen Gulf on 22 December. On 26 December 1941 Manila was declared an open city, with the Philippine government and MacArthur's headquarters evacuated to the Malinta Tunnel. Amid the evacuations, a re-inauguration ceremony for Philippine President Manuel Quezon's second term was held just outside the tunnel on 30 December.[29] The Japanese entered Manila on 2 January 1942.[30] Five days later the U.S. and Philippine forces completed a fighting withdrawal to the Bataan peninsula, northwest of Corregidor, and prepared to defend it. In the northern Philippines, this left only Bataan, Corregidor, and Forts Hughes, Frank, and Drum in Allied hands.[31] This situation had been anticipated in the prewar War Plan Orange-3, under which the forces in the Philippines were expected to hold out at the mouth of Manila Bay for six months. By that time it was anticipated that a relief expedition from the U.S. might arrive. General MacArthur had hoped to defend the Philippines more aggressively under the Rainbow Plan, and was able to get some reinforcements in the months prior to the U.S. entering the war, but this fell apart with the rapid Japanese advance in December 1941. And, with almost all of the Pacific Fleet's battleships sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor, and the Japanese advancing in several parts of Southeast Asia at a much greater rate than expected, no relief was organized. Although extensive guerrilla operations were conducted by Filipinos with U.S. support, U.S. forces did not return to the Philippines in strength until the invasion of Leyte Gulf in October 1944.[32]

One aspect of MacArthur's Rainbow Plan was the Inland Seas Project, intended to defend a shipping route to keep his forces supplied. Part of this was a buildup of Philippine Commonwealth forces, and a projected deployment of coast artillery weapons manned by them in the central Philippines. In 1940-41 eight 8-inch (203 mm) railway guns and 24 155 mm (6.1 in) GPF guns were delivered to the Philippines, without crews as they were to be locally manned. The 8-inch guns were sent north in December 1941 to engage the invading Japanese forces, but six of them were destroyed by air attack. One gun was eventually placed on a fixed mount as Battery RJ-43 on Corregidor in March 1942; the other may have been at Bagac, Bataan. Reportedly the Corregidor gun fired only five proof rounds, then went unused for lack of a crew until knocked off its mount by bombing or shelling. The history of the Bataan gun is unknown. Most or all of the 24 155 mm GPF guns were eventually deployed at Corregidor and/or Bataan.[33][34]

Fall of Bataan

Although the US and Filipino forces achieved success in defending Bataan through the end of February,[35] they had taken 50 percent casualties and were worn out and poorly supplied.[36] Also, the British fortress of Singapore had surrendered on 15 February, and the Japanese had taken several major islands of the Dutch East Indies, essentially preventing any reinforcement of the Philippines. Philippine President Manuel Quezon, with his family and senior officials, was evacuated to the southern Philippines by the submarine USS Swordfish (SS-193) on 20 February.[37] MacArthur was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to relocate to Australia to prevent his capture and to direct further operations. He departed Corregidor on 12 March 1942, initially by PT boat to Mindanao, completing his journey by air. On 20 March he made a speech with the famous phrase "I shall return". He left Lieutenant General Jonathan M. Wainwright IV in a subordinate command in the Philippines, telling the key officers there that he (MacArthur) would control the Philippines from Australia. However, he neglected to inform Washington of this arrangement, and Washington intended Wainwright to be in charge. It was not until 20 March that the extent of Wainwright's authority and degree of independence from MacArthur was clarified by a message from General George C. Marshall, the Army chief of staff.[38]

The Japanese in Bataan received substantial reinforcements and replacements in March, including 240 mm howitzers and aircraft, and prepared for an offensive scheduled for 3 April.[39] It started with a five-hour air and artillery bombardment that destroyed many of the Allied defensive positions and stunned the defenders; a three-day assault threw them back along much of the line.[40] On 6 April the US and Filipino forces attempted a counterattack, which ran into a fresh Japanese attack that eventually threw the Allies further back.[41] Over the next two days many Allied units disintegrated, and on 9 April the Allied forces on Bataan surrendered.[42] About 2,000 stragglers made it to Corregidor, while about 78,000 became prisoners of the Japanese and were transferred to camps in northern Luzon on the Bataan Death March.[43]

Fall of Corregidor

Corregidor had been bombed intermittently since 29 December 1941. Supplies on the island were short, with food and water severely rationed and the defenders correspondingly weakened. Japanese artillery bombardment of Corregidor began immediately after the fall of Bataan on 9 April. It became intense over the next few weeks as more guns were brought up, and one day's shelling was said to equal all the bombing raids combined in damage inflicted. However, after an initial response from a 155 mm GPF battery, Lt. Gen. Wainwright prohibited counterbattery fire for three days, fearing there were wounded POWs on Bataan who might be killed.[44] Japanese aircraft flew 614 missions, dropping 1,701 bombs totaling some 365 tons of explosive. Joining the aerial bombardment were nine 240 mm (9.45 in) howitzers, thirty-four 149 mm (5.9 in) howitzers, and 32 other artillery pieces, which pounded Corregidor day and night. It was estimated that on 4 May alone, more than 16,000 shells hit Corregidor.[45] Forts Frank and Drum had been bombarded from the Pico de Loro hills on the Cavite shore since 6 February by a gradually increasing Japanese artillery force.[46]

On 3 February 1942 USS Trout (SS-202) arrived at Corregidor with 3,500 rounds of 3-inch anti-aircraft ammunition. Along with mail and important documents, Trout was loaded with 20 tons of gold and silver previously removed from banks in the Philippines before departing.[47]

By the end of April Corregidor's main power plant was too damaged to function most of the time. This was needed for the ammunition hoists of the disappearing gun batteries, which had gasoline-powered generators but for which fuel could not be spared. The Malinta Tunnel had its own generators, but sometimes these failed too.[48] The bombardment by high-angle artillery and aircraft gradually destroyed the utility of almost all of Corregidor's big guns, which had no overhead protection except for magazines and generators. The 12-inch (305 mm) mortars of Battery Geary and Battery Way fared better until near the end; their battery arrangement did not require electric power for ammunition hoists. However, Battery Way at least had been out of service for years; only three mortars were restored to service and these not until 28 April, and by 5 May two of these were out of action. There was also a shortage of high explosive shells, and adapting the armor piercing shells for instantaneous detonation was time-consuming at only 25 shells per day. On 2 May a 240 mm shell penetrated one of Battery Geary's magazines; the resulting explosion put the entire battery out of action, blowing one mortar 150 yards (140 m) from the battery and embedding another mortar entirely inside another magazine.[49] Among the harbor forts, only Fort Drum's turrets proved impregnable to attack; they remained in action until the surrender despite damage to other parts of the fort.[50]

On the night of 4 May a submarine returning to Australia from patrol evacuated 25 persons. Among the passengers were Colonel Constant Irwin, who carried a complete roster of all Army, Navy, and Marine personnel still alive; Col. Royal G. Jenks, a finance officer, with financial accounts; Col. Milton A. Hill, the inspector general, 3 other Army and 6 Navy officers, and about 13 nurses. Included in the cargo sent from Corregidor were several bags of mail, the last to go out of the Philippines, and "many USAFFE and USFIP records and orders".[51]

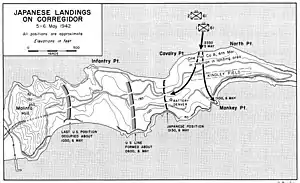

The bombardment increased in intensity through 5 May, and the Japanese landed that night. Their initial landing was near the east end of the island, north of Kindley Field, the airstrip. This was somewhat east of their objective, which was between Infantry Point and Cavalry Point, due to a miscalculation of the current.[52] The 4th Marine Regiment coordinated the ground forces, which included many soldiers and sailors from support units untrained in ground combat, many of them escapees from Bataan. Several coast artillery and antiaircraft batteries were abandoned to free their crews as ground forces.[53] Of 229 officers and 3,770 enlisted men attached to the regiment, only around 1,500 were US Marines. The Japanese landed on the night of 5 May about 2300, with 75 mm and 37 mm guns deployed for beach defense reportedly causing them heavy casualties. At least three of the 155 mm guns were also still in action. However, by 0130 the Japanese captured Battery Denver, turning back three Allied counterattacks by 0400. At dawn, around 0440, more invasion barges were spotted and fire support from Fort Drum's 14-inch (356 mm) guns was requested. Although smoke obscured the barges, Fort Drum was directed to fire "anywhere between you and Cabcaben" (in Bataan), and over 100 rounds were fired on the invasion route.[53] By 1000 the Japanese were firmly lodged on the island. With 600-800 Allied troops killed and over 1,000 wounded, no reserves were left. No one was available to evacuate the wounded, and most of those who attempted to walk to the Malinta Tunnel were either further wounded or killed. General Wainwright felt certain that further Japanese troops would land in the night and seize the Malinta Tunnel, where they might massacre the wounded and noncombatants. He decided to sacrifice one day of freedom to save several thousand lives. After giving orders to his forces to destroy their weapons to prevent their use by the enemy, he surrendered.[54]

Although all the harbor forts were included in the surrender, General Wainwright made every effort to avoid surrendering the troops in the southern Philippines. He sent an order placing them directly under MacArthur just before surrendering Corregidor. However, the Japanese insisted that all US and Filipino forces in the islands be included, and stated they would not cease offensive operations until that took place. Wainwright believed this meant they might start executing the 10,000 or so prisoners from Corregidor and the other forts, so he ordered the surrender of all forces. The units in the south were in much better positions for both supplies and continued resistance than those at Bataan or Corregidor were, and their commanders believed Wainwright's surrender orders were made under duress. It was not until 9 June that the Japanese accepted that all of the islands had surrendered. Some units never did surrender, and became nuclei for guerrilla operations that continued until the Japanese were mostly killed or captured in early 1945, following MacArthur's return to the Philippines in force in October 1944.[32][55]

The conquest of the Philippines by Japan is often considered the worst military defeat in United States history.[56] About 23,000 American military personnel were killed or captured, while Filipino soldiers killed or captured totaled around 100,000.[57]

The Philippines, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies were the last major territories the Japanese invaded in World War II, all captured in early 1942. As Corregidor surrendered, the Battle of the Coral Sea was in progress, turning back a Japanese attempt to seize Port Moresby, New Guinea by sea. By the final surrender on 9 June, the Battle of Midway was over, blunting Japan's naval strength with the loss of four large aircraft carriers and hundreds of skilled pilots. Both of these victories were costly to the US Navy as well, with two aircraft carriers lost, but the United States could replace their ships and train more pilots, and Japan, for the most part, could not do so adequately.

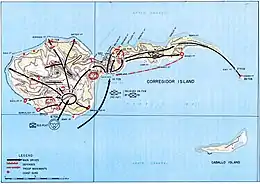

Recapture of Corregidor

US forces returned to the Philippines in a major invasion at Leyte beginning on 20 October 1944, with General MacArthur soon declaring "I have returned". The Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the invasion fleet on 23–26 October in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the war, but were repulsed with heavy losses.[58] By early February 1945 much of the Manila area[59] and part of Bataan[60] had been secured. Corregidor was the biggest obstacle to reopening Manila Bay to shipping. A risky operation to recapture the island via near-simultaneous airborne and amphibious assault was devised. The invasion was set for 16 February. Air bombardment began on 22 January, and naval bombardment on 13 February.[61] The easiest place for a parachute drop on the island was Kindley Field, the disused airstrip. However, this would put the paratroops in an exposed position, and planners decided to immediately seize the island's high ground with a drop on Topside, the western part of the island. Only two barely-adequate drop zones were available: the parade ground and the former golf course. Each plane would have to make two or three passes to unload all of the paratroopers and equipment on these small areas. The drop would also have to be divided into two lifts, separated by at least four hours. Each lift could carry a reinforced battalion, and another drop was planned for the 17th to deliver the remainder of the regimental combat team.[62] The overall plan was for the first airborne assault at 0830, the amphibious landing at 1030, and the second airborne lift at 1215. The airborne force was the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team of Lieutenant Colonel George M. Jones. The 503rd PRCT drop force included the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, Co. C, 161st Airborne Engineer Battalion, and elements of the 462nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion with 75 mm pack howitzers.[63] They were airlifted by C-47 aircraft of the 317th Troop Carrier Group. The amphibious assault was by the reinforced 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division, carried by Landing Craft Mechanized (LCMs) of the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade.[64][65] Japanese forces were estimated at 850. There were actually about 5,000 Japanese military personnel on the island, primarily naval forces under Japanese Navy Captain Akira Itagaki. Surprisingly, the low initial estimate of Japanese strength did not become a major problem.[66]

The airborne assault began on schedule at 0833 on 16 February 1945. It achieved surprise and Japanese resistance was light. However, a higher drop altitude and stronger winds than planned, combined with the small drop zones, resulted in a 25 percent injury rate. Many troops landed outside the drop zones in wooded or rocky areas, or on ruined buildings and gun batteries. One group of paratroopers landed on an observation post that included the Japanese commander, and killed him. The amphibious assault at 1030 on the south shore of Bottomside at San Jose was also successful, despite encountering land mines. The surface of Malinta Hill was captured in half an hour, although numerous Japanese remained in the Malinta Tunnel below it. The second paratroop lift dropped at 1240, with a much lower injury rate than the first lift. However, due to the success of the attack, the commander of the 503rd decided to cancel the drop scheduled for the 17th, and bring the remaining paratroops in by sea. The combined forces on Corregidor became known as "Rock Force".[67][65]

As well as the force in the Malinta Tunnel, the Japanese were dug in on various parts of the island, occupying numerous tunnels and small bunkers. Many of these were south and west of Topside. Rock Force cleared the bunkers in the typical fashion of the war in the Pacific: air-delivered napalm bombs where needed, followed by assaults with flamethrowers and white phosphorus grenades among other weapons. The Japanese would sometimes reoccupy these positions at night. In some cases demolition charges were used to entomb the Japanese in their bunkers and tunnels.[68] The Japanese occasionally made banzai charges at this point in the war, which mainly succeeded in increasing their own casualties. There were attempts made to persuade the Japanese to surrender, but few did so. On at least three occasions the Japanese were able to detonate ammunition caches near American troops, usually followed by an attack, though these tactics killed more Japanese than Americans. The most spectacular of these was the detonation of a large amount of explosives in the Malinta Tunnel on the night of 21 February. Apparently the intention was to shock the Americans on and near Malinta Hill and allow the force in the tunnel to escape eastward to the island's tail. However, it appeared that the explosion was larger than intended, though perhaps several hundred Japanese out of an estimated 2,000 in the tunnel were able to join their main force on the tail. Two nights later more explosions shook Malinta Hill, probably the suicide of its remaining defenders.[68] By this time the entire western part of the island was cleared and preparations made to clear the tail area. On 24 February the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry was relieved by the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry of the 38th Infantry Division. At 1100 on 26 February the Japanese apparently decided to finish themselves and take some Americans with them, setting off an ammunition-filled bunker at Monkey Point. Perhaps 200 Japanese were killed outright, along with 50 Americans killed and 150 wounded. Within a few hours the only Japanese left alive were in a few caves along the island's waterline, who were mopped up in a few days.[68]

Corregidor's flags

Flag re-hoisted during bombardment

On 16 April 1942, during an intense Japanese artillery bombardment, the 100-foot flagpole's halyard was severed and the flag began to come down. Four men of Battery B, 60th Coast Artillery (AA), including Captain Arthur E. Huff, left shelter to catch the flag before it reached the ground. They repaired the halyard, re-raised the flag, and returned to shelter. Each of them received the Silver Star.[69]

Pieces of flag preserved

Just before surrendering on 6 May 1942, Colonel Paul Bunker, commander of the 59th Coast Artillery and the Seaward Defenses, followed General Wainwright's orders to haul down and burn Corregidor's flag, to avoid turning it over to the Japanese, and run up the white flag. He kept a piece of the American flag that he sewed into his clothing.[70]

On 10 June 1942, in the Bilibid Prison hospital, Manila, Bunker sent for Colonel Delbert Ausmus, cut the flag remnant into two pieces and gave one of the pieces to Ausmus. He told Colonel Ausmus he did not expect to survive the prison camp and that it was Ausmus' duty to take his piece of the flag to the Secretary of War.[71] Ausmus concealed the remnant in his shirt cuff, and shortly after the war ended, Ausmus delivered it to Secretary Patterson.[71] In November 1945, Ausmus described the circumstances under which he received the remnant from Bunker:

"He was taken to Bilibid prison in Manila and came down with pneumonia. While he was in the hospital Col. Paul D. Bunker of Taunton, Mass., was brought in suffering from seriously infected blisters on his feet and blood poisoning in one leg. On June 10, Bunker watching carefully 'to see that there were no Japs near,' swore him to secrecy, Ausmus continued, and 'said he wanted to turn something over to me to deliver to the Secretary of War.' From beneath a false patch set into the left pocket of his shirt Bunker took a bit of red cloth. Solemnly he gave Ausmus part of it and put the rest back."[72]

On 16 March 1943, Colonel Bunker died in a Japanese prison camp in Karenko, Taiwan. While giving one piece of the flag to Ausmus, he held onto another piece until the time of his death. General Wainwright later recalled the circumstances of Bunker's death in the prison camp, still holding onto the remnant: "He must have suffered ... constant pain of hunger ... I sat with him for a part of the last two hours of his life ... [He was] cremated in the rags in which he had carefully sewn a bit of the American flag he had pulled down in Corregidor."[73]

Ausmus did deliver it to the Secretary of War who unveiled it during a speech on the event of Flag Day in June 1946.[71] The remnant of the U.S. flag from Corregidor saved by Bunker and Ausmus is on display in the West Point museum.[74]

Flag raised again on Corregidor

On 2 March 1945, with Corregidor secured, a flag-raising ceremony with General MacArthur present was held at Topside. With a new flag raised, Colonel Jones of the 503rd Parachute Infantry saluted the general and said simply, "Sir, I present to you Fortress Corregidor."[75]

Present

The ruins of Fort Mills are impressive, and feature the largest concentration of surviving US coast defense guns in the world. Including spare barrels, twelve 12-inch (305 mm) guns, ten 12-inch (305 mm) mortars, three 10-inch (254 mm) guns, one 8-inch (203 mm) gun, and five 6-inch (152 mm) guns are on the island.[76][77]

See also

References

- Morton, p. 478

- Forts in the Philippines at American Forts Network

- Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays at the Coast Defense Study Group

- Fort and battery names at Corregidor.org

- McGovern and Berhow 2003, pp. 7-12

- Berhow 2015, p. 430

- Morton, p. 473

- Berhow 2015, pp. 222, 233-240

- Battery Geary's four M1890 mortars were transferred from Battery Whitman at Fort Andrews, Massachusetts.Battery Whitman at FortWiki.com

- Lewis, pp. 83-89

- Battery Hall, Fort Saulsbury, Delaware at FortWiki.com, with the same weapons as Batteries Smith and Hearn

- Berhow 2015, p. 61

- Berhow 2015, pp. 227-228

- Evans, David; Peattie, Mark (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 199. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Berhow 2015, p. 194

- Order of Names at Corregidor.org

- Map at "The Sinking of SS Corregidor" at MaritimeReview.ph

- Some accounts indicate the ship sank near La Monja Island, but this would mean the ship somehow got through the Corregidor-Bataan Army minefield.

- Gordon, John (2011). Fighting for MacArthur: The Navy and Marine Corps' Desperate Defense of the Philippines. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 73–76. ISBN 978-1-61251-062-0.

- Discussion with quotes from several sources about the sinking of SS Corregidor at Corregidor.com

- Diary of CPT George Steiger, entry for 19 December 1941

- Strong, Paschal N., The Lean Years, p. 2 at Corregidor.org

- A French design, designated Grand Puissance Filloux for its designer.

- Gaines, William C., Coast Artillery Organizational History, 1917-1950, Coast Defense Journal, vol. 23, issue 2, pp. 34-35

- Morton, p. 474

- Table of Armaments & Coast Artillery Assignments at corregidor.org

- Major General when recalled, promoted two days later.

- Morton, p. 19

- Morton, pp. 491-492

- Morton, pp. 232-238

- Morton, pp. 230-231

- Morton, pp. 61-70

- The Doomed Philippine Inland Seas Defense Project

- Account of the 8" railway guns in the Philippines, 1940-42

- Morton, Ch. XVII, XVIII, XIX

- Morton, pp. 367-380

- "Swordfish I (SS-193)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command.

- Morton, pp. 353-366

- Morton, pp. 413-414

- Morton, pp. 421-426, 430

- Morton, pp. 445-441

- Morton, Ch. XXVI

- Morton, p. 461

- Morton, p. 536

- Morton, p. 549

- Bogart, Charles. "Carabao Island's Fort Frank". The Corregidor Historical Society. Retrieved on 10 March 2018.

- "Trout I (SS-202)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval Historical Center. 1970.

- Morton, p. 546

- Morton, pp. 540-541

- Morton, pp. 486-487, 540

- Morton, p. 548

- Morton, pp. 553-554

- Morton, pp. 556-558

- Morton, pp. 560-561

- Morton, Ch. XXXII

- "War in the Pacific: The First Year", accessed 4 May 2016

- "American Prisoners of War in the Philippines", Office of the Provost Marshal, November 19, 1945, accessed 4 May 2016

- "The Largest Naval Battles in Military History: A Closer Look at the Largest and Most Influential Naval Battles in World History". Military History. Norwich University. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Smith 1963, Ch. XVI

- Smith 1963, Ch. XVII

- Smith 1963, p. 340

- Smith 1963, pp. 337-338

- Smith 1963 also lists the 162nd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, but it is not in the Rock Force list, and Stanton 1991, p. 401 shows this was not a parachute unit and it served in Europe. This may refer to fire support from Corregidor in the later recapture of Caballo Island by the 163rd Field Artillery Battalion, as listed at RockForce.org.

- Smith 1963, p. 341

- List of Rock Force units at Rockforce.org

- Smith 1963, pp. 339-340

- Smith 1963, pp. 341-345

- Smith 1963, pp. 345-348

- Morton, p. 538

- Duane Heisinger. "Father Found, p. 41".

- "Flag Day Brings Memories Of Heroism To Gen. Brougher". Anniston Star (Alabama). 1946-06-16.

- "Last Tattered Fragment of Flag Lowered At Corregidor Is Delivered in Washington". Abilene Reporter-News. 1945-11-15.

- Heisinger, Father Found, p. 41

- "The Class of 1903". The MacArthur Memorial.

- Smith 1963, pp. 348-349

- Berhow 2015, pp. 232-236

- Surviving American seacoast artillery weapons at the Coast Defense Study Group (PDF)

- Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Third Edition. McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- McGovern, Terrance; Berhow, Mark A. (2003). American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898-1945 (Fortress, 4). Osprey Publishing (UK). ISBN 1-84176-427-2.

- Morton, Louis (1953). The Fall of the Philippines. U.S. Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-2.

- Smith, Robert Ross (1993) [1963]. Triumph in the Philippines (PDF). U.S. Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-10-1.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Mills, Corregidor. |

- Corregidor Historical Society website (includes Corregidor.org and RockForce.org)

- Coast Artillery Battery assignments in the Philippines at Corregidor.org

- Forts in the Philippines at American Forts Network

- Surviving American seacoast artillery weapons at the Coast Defense Study Group (PDF)

- Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays at the Coast Defense Study Group

- Maps of US forts in the Philippines at the Coast Defense Study Group