Battle of Bataan

The Battle of Bataan (Filipino: Labanan sa Bataan) (7 January – 9 April 1942) was fought by the United States and the Philippine Commonwealth against Japan during World War II. The battle represented the most intense phase of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines during World War II. In January 1942, forces of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy invaded Luzon along with several islands in the Philippine Archipelago after the bombing of the American naval base at Pearl Harbor.

| Battle of Bataan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippines Campaign in World War II | |||||||

Japanese tank column advancing in the Bataan Peninsula | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120,000 U.S. and Filipino troops | 75,000 Japanese troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

106,000 10,000 killed, 20,000 wounded, 76,000 captured[1] |

8,406[2]–22,250[3] 3,107 killed, 230 missing, 5,069 wounded | ||||||

The commander-in-chief of all U.S. and Filipino forces in the islands, General Douglas MacArthur, consolidated all of his Luzon-based units on the Bataan Peninsula to fight against the Japanese army. By this time, the Japanese controlled nearly all of Southeast Asia. The Bataan Peninsula and the island of Corregidor were the only remaining Allied strongholds in the region.

Despite a lack of supplies, American and Filipino forces managed to fight the Japanese for three months, engaging them initially in a fighting retreat southward. As the combined American and Filipino forces made a last stand, the delay cost the Japanese valuable time and prevented immediate victory across the Pacific. The American surrender at Bataan to the Japanese, with 76,000 soldiers surrendering in the Philippines altogether,[1] was the largest in American and Filipino military histories, and was the largest United States surrender since the American Civil War's Battle of Harper's Ferry.[4] Soon afterwards, U.S. and Filipino prisoners of war were forced into the Bataan Death March.[5]

Background

The capture of the Philippine Islands was crucial to Japan's effort to control the Southwest Pacific, seize the resource-rich Dutch East Indies, and protect its Southeast Asian flank. In late summer 1941, the Roosevelt Administration began a series of moves toward Japan that could only conclude with war. It began supplying arms to Chiang Kai-Shek in China, began a massive military build-up in the Philippines and imposed a series of embargoes, most importantly a refusal to sell Japan petroleum unless they evacuated all of China, including Manchuko (Manchuria). This "ultimatum" was rejected by Japan and the fuse was lit.

After Japanese carrier planes attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 December 1941 (8 December, Manila time), Taiwan-based aircraft, within seven hours, pounded the main bases of the American Far East Air Force at Clark Field in Pampanga, Iba Field in Zambales, Nichols Field near Manila, and the headquarters of the United States Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines, at Cavite. Many American planes were caught on the ground and summarily destroyed. In one day, the Japanese had gained air superiority over the Philippine Islands. This forced the U.S. Asiatic Fleet to withdraw its surface ships from its naval base in Cavite and retreat southwards, leaving only the submarine force to resist the Japanese with untested, faulty torpedoes.

From 8 to 10 December, scattered resistance by ground troops and remaining American air and naval forces failed to stop preliminary landings to seize airfields at Batan Island, Aparri, and Vigan City. Army Air Force B-17s, often with little if any fighter escort, attacked Japanese ships offloading at Gonzaga and the Vigan landings on Luzon with no effect. Submarines of the Asiatic Fleet were also assigned to the effort.

In one last coordinated action by the Far East Air Force, U.S. planes damaged two Japanese transports and a destroyer, and sank one minesweeper. Army Air Corps pilot Sam Marrett was killed while on his successful attack against the minesweeper. These air attacks and naval actions, however, did not significantly delay the Japanese assault.[6]

These small-scale landings preceded the main assault on 22 December 1941, at Lingayen Gulf in Pangasinan and Lamon Bay, Tayabas, by the 14th Japanese Imperial Army, led by Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma.

By effectively neutralizing U.S. air and naval power in the Philippines, the Japanese gained supremacy that isolated the Philippines from reinforcement and resupply, and provided itself with both airfields for support of its invasion forces and staging bases for further operations in the Dutch East Indies.

War Plan Orange-3

When MacArthur returned to active duty, the latest revision plans for the defense of the Philippine Islands had been completed in April 1941 and was called WPO-3, based on the joint Army-Navy War Plan Orange of 1938, which involved hostilities between the United States and Japan.[7] Under WPO-3, the Philippine garrison was to hold the entrance to Manila Bay and deny its use to Japanese naval forces and ground forces were to prevent enemy landings. If the enemy prevailed, they were to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula, which was recognized as the key to the control of Manila Bay. It was to be defended to the "last extremity".[7] In addition to the regular U.S. Army troops, the defenders could rely on the Philippine Army, which had been organized and trained by General MacArthur.[7]

However, in April 1941, the Navy estimated that it would require at least two years for the Pacific Fleet to fight its way across the Pacific. Army planners in early 1941 believed supplies would be exhausted within six months and the garrison would fall.[7] MacArthur assumed command of the Allied army in July 1941 and rejected WPO-3 as defeatist, preferring a more aggressive course of action.[8] He recommended—among other things—a coastal defense strategy that would include the entire archipelago. His recommendations were followed in the plan that was eventually approved.[7] Due to MacArthur's decision, with tacit approval from Washington, to change the plan under War Plan Rainbow 5, it was ordered that the entire archipelago would be defended, with the necessary supplies dispersed behind the beachheads for defending forces to use while defending against the landings. With the return to War Plan Orange 3, the necessary supplies to support the defenders for the anticipated six-month-long defensive position were not available in the necessary quantities for the defenders who would withdraw to Bataan.[9]

Battle

When the Japanese made their first landings on 10 and 12 December at the northern and southern extremities of Luzon, General MacArthur made no disposition to contest them. He correctly surmised that these landings were designed to secure advance air bases and that the Japanese had no intention of driving on Manila from any of these beachheads. He did not regard the situation as serious enough to warrant a change in his plan to oppose the main attack, when it came, with an all-out defense at the beaches. The MacArthur Plan, then, remained in effect.[7]

On December 20, US Navy submarine USS Stingray spotted a large convoy of troop ships with escorts. This was General Homma's landing force, and included 85 troop transports, two battleships, six cruisers, and two dozen destroyers. The convoy was engaged by three submarines: USS Stingray, USS Saury, and USS Salmon, who fired torpedo after torpedo into the convoy, most of which failed to explode, due to the Mark XIV torpedo's defective detonators. In all, just two troop ships were sunk before Japanese destroyers chased the submarines away.[10]

Fighting retreat

General MacArthur intended to move his men with their equipment and supplies in good order to their defensive positions. He charged the North Luzon Force under Maj. Gen. Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright IV with holding back the main Japanese assault and keeping the road to Bataan open for use by the South Luzon Force of Maj. Gen. George Parker, which proceeded quickly and in remarkably good order, given the chaotic situation. To achieve this, Wainwright deployed his forces in a series of five defensive lines outlined in WPO-3:

- D1: Aguilar to San Carlos to Urdaneta City

- D2: Agno River

- D3: Santa Ignacia to Gerona to Guimba to San Jose

- D4: Tarlac to Cabanatuan City

- D5: Bamban to Sibul Springs

Layac Line

The main force of General Masaharu Homma's 14th Area Army came ashore at Lingayen Gulf on the morning of 22 December. The defenders failed to hold the beaches. By the end of the day, the Japanese had secured most of their objectives and were in position to emerge onto the central plain.[7] Facing Homma's troops were four Filipino divisions: the 21st, the 71st, the 11th, and the 91st, as well as a battalion of Philippine Scouts backed by a few tanks.[10] Along Route 3—a cobblestone road that led directly to Manila[10]—the Japanese soon made contact with the Filipino 71st Division. At this point the action of the American artillery stalled the Japanese attack. However, Japanese planes and tanks entering the action routed the Filipino infantry, leaving the artillery uncovered.[7] A second Japanese division landed at Lamon Bay, south of Manila, on December 23 and advanced north.[11]

It was now evident to General Wainwright that he could no longer hold back the Japanese advance. Late on the afternoon of the 23rd, Wainwright telephoned General MacArthur's headquarters in Manila and informed him that any further defense of the Lingayen beaches was "impracticable." He requested and was given permission to withdraw behind the Agno River.[7] MacArthur weighed two choices: either make a firm stand on the line of the Agno and give Wainwright his best unit, the Philippine Division, for a counterattack; or withdraw all the way to Bataan in planned stages. He decided on the latter, thus abandoning his own plan for defense and reverting to the old ORANGE plan. Having made his decision to withdraw to Bataan, MacArthur notified all force commanders on the night of 23 December that "WPO-3 is in effect."[7]

Meanwhile, Manuel L. Quezon, the President of the Philippine Commonwealth, together with his family and government staff were evacuated to Corregidor, along with MacArthur's United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) headquarters, on the night of 24 December 1941, while all USAFFE military personnel were removed from the major urban areas. On the 26th Manila was officially declared an open city and MacArthur's proclamation was published in the newspapers and broadcast over the radio. The Japanese were not notified officially of the proclamation but learned of it through radio broadcasts. The next day, and thereafter, they bombed the port area, from which supplies were being shipped to Bataan and Corregidor.[7]

After General Douglas MacArthur had withdrawn his army down the island of Luzon's central plain into the Bataan Peninsula, one last line existed before the Japanese invaders reached the main line of resistance. The Americans attempted to slow the Japanese entry into Bataan by fighting a delaying action at Layac, thus gaining time and deceiving the enemy as to the location of the main defensive positions. For the first time in World War II, American troops faced Japanese soldiers on the ground.

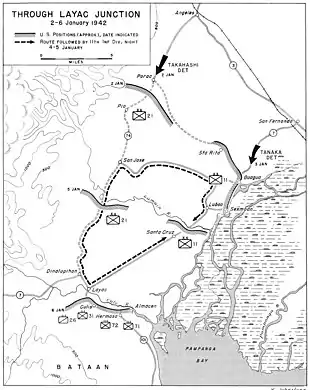

Porac–Guagua Line

From 1 to 5 January 1942, as the entire USAFFE converged from south and north, delaying actions were fought to allow the struggling withdrawal to Bataan. The fiercest fighting occurred at the hastily emplaced Porac–Guagua Line, where the 11th and 21st divisions, respectively led by Brigadier Generals William E. Brougher and Mateo Capinpin, with the 26th Cavalry Regiment of Colonel Clinton A. Pierce in reserve, held the line, mostly on open and unprepared ground, against massive aerial and artillery bombardment, strong tank assaults, and infantry banzai attacks by the Takahashi and Tanaka detachments. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

Overlooked in this report are the actions of the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the PA, led by senior instructor Col. Wallace A Mead. The 23rd Regiment established the defensive line at Porac-Pampanga on or around 2 January 1942. Colonel Mead was later awarded the Silver Star for his actions there. The 23rd's defense allowed Capinpin's forces to withdraw and establish new defensive positions. It was Capinpin's recount of the fighting that day that was offered as support for Mead's citation.

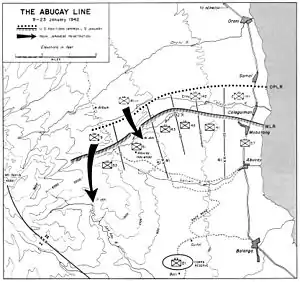

Abucay–Mauban Line

War Plan Orange 3 called for two defensive lines across Bataan. The first extended across the peninsula from Mauban in the west to Mabatang, Abucay in the east. General Wainwright, commanding the newly organised I Philippine Corps of 22,500 troops, held the western sector. I Corps included the Philippine Army's 1st Regular, 31st, and 91st Divisions, the 26th Cavalry (Philippine Scouts (PS)) and a battery of field artillery and self-propelled guns. General Parker and the new II Philippine Corps, which included the Philippine Army's 11th, 21st, 41st, and 51st divisions and the 57th Infantry (PS), and numbered 25,000 men, defended the eastern sector. All of the divisions, already under strength at the onset of war, had suffered serious combat losses, particularly to desertions. The U.S. Army's Philippine Division, made up of the 31st Infantry, the 45th Infantry (PS), and supporting units became the "Bataan Defense Force Reserve". Mount Natib, a 4,222-foot (1,287 m)-high mountain that split the peninsula, served as the boundary line between the two corps. The commanders anchored their lines on the mountain, but, since they considered the rugged terrain impassable, they did not extend their forces far up its slopes. The two corps were therefore not in direct contact with each other, leaving a serious gap in the defense line. With the fighting withdrawal completed, the Abucay–Mauban Line, the USAFFE's main battle position was now in place.

Stand

On 9 January, Japanese forces under Lieutenant General Susumu Morioka assaulted the eastern flank of the Abucay–Mauban Line, and were repulsed by the 91st Division of Brigadier General Luther Stevens and Colonel George S. Clark's 57th Infantry (PS). On 12 January, amid fierce fighting, 2nd Lieutenant Alexander R. Nininger, a platoon leader in the 57th Infantry, sacrificed his life when, armed with only a rifle and hand grenades, he forced his way into enemy foxholes during hand-to-hand combat, permitting his unit to retake Abucay Hacienda; for his actions, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Another extreme act of bravery was put forth by a Filipino named Narciso Ortilano.[12] He was on a water-cooled heavy machine gun when the Japanese burst out of a canebrake in a banzai attack. He shot dozens of the Japanese with his machine gun, then pulled out his Colt .45 and shot five more when the machine gun jammed. Then, when one Japanese soldier stabbed at him with a bayonet, he desperately tried to grab the gun, got his thumb cut off, but still held on, and then with a sudden burst of adrenaline he turned the gun on the enemy soldier and stabbed him in the chest. When another Japanese soldier swung a bayonet at him, he turned his rifle on the soldier and shot him dead. Narcisco received the Distinguished Service Cross.[12]

Another attack on 14 January at the boundary of positions held by the 41st and 51st Divisions of Brigadier Generals Vicente Lim and Albert M. Jones, respectively, aided by the 43rd and Colonel Wallace A Mead's 23rd Infantry, stubbornly refused the Japanese their left flank. The Japanese advanced to the Salian River Valley through a gap made by the 51st Infantry's withdrawal. But a patrol discovered the infiltration, and units of the 21st Division rushed to the valley and repulsed the attackers after a savage encounter.

At another engagement farther to the west, a Japanese force surprised and routed the 53rd Infantry of Colonel John R. Boatwright. This force also penetrated deep behind the Abucay–Mauban Line along the Abo-Abo River Valley, but their advance was held up by combined units of the 21st and 51st Divisions, the 31st Division of Brigadier General Clifford Bluemel, and Colonel John H. Rodman's 92nd Infantry at the Bani-Guirol Forest area. The 31st Infantry and the 45th Infantry, Philippine scouts of Colonel Thomas W. Doyle, partially restored the abandoned line of the 51st Division.

On 15 January, the reinforced 1st Regular Division of Brigadier General Fidel Segundo, defending the Morong sector, came under heavy bombardment, but held the line. The Japanese penetrated through a huge gap in the Silangan-Natib area and established a roadblock on Mauban Ridge, threatening to cut off the division's rear. Repeated attacks by the 91st Division and 71st Division, and 92nd Infantry failed to dislodge the Japanese. The attackers' nightly raids and infiltration tactics became more frequent. Previously, General Parker's II Corps had prevented a similar encirclement at the Salian River battle, but the position of General Wainwright's I Corps was deemed indefensible, and the Abucay–Mauban Line was abandoned on 22 January.

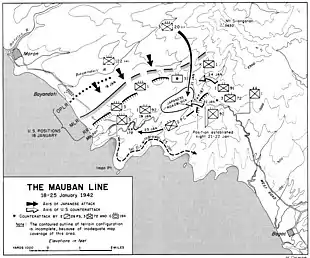

Battle of Trail Two

Within four days, the Orion-Bagac Line was formed. But the defenders had yet to complete their withdrawal to the reserve battle position when the Japanese struck again, through a gap held by I Corps. General Bluemel hastily organized a defense along Trail Two, consisting of 32nd Infantry, 41st Infantry and 51st Division reinforcements, in time to stop a major offensive and plug the gap.

Battle of the Pockets

The remaining Japanese troops managed to get through, however, and held out at some rear sectors of the Orion-Bagac Line at the Tuol River Valley behind the 11th Division, and in the Gogo-Cotar River behind the 1st Regular Division. From 23 January to 17 February, coordinated action by the defenders to eliminate these salients of resistance became known as the "Battle of the pockets". Fierce fighting marked the action. Captain Alfredo M. Santos, of the 1st Regular Division, outmaneuvered the enemy during their attempt to pocket the area. In both attempts, his unit successfully broke through the Gogo-Cotar and Tuol pockets, thus earning for himself the moniker "hero of the pockets". For his successes, he was promoted to major in the field. Major Santos was then given the hazardous mission of closing the gaps and annihilating the enemy troops who had infiltrated the lines, as the gap posed a serious threat to the positions and the security of the division. He led a counterattack against the strong and numerically superior Japanese forces positioned between the MLR and the Regimental Reserve Line (RRL). The fighting began at dawn on 29 January 1942, and the Americans restored the defensive sector assigned to the 1st Regular Division. On 3 February 1942, 1st Lieutenant Willibald C. Bianchi of the 45th Infantry, Philippine scouts, led a reinforced platoon forward against two enemy machine-gun nests, silenced them with grenades, and despite two machine gun wounds to the chest, then manned an antiaircraft machine gun until being knocked off the tank by a third severe wound.[13] He was awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions. Of the 2,000 Japanese soldiers engaged, 377 were reported to have escaped.

General Homma, on 8 February, ordered the suspension of offensive operations in order to reorganize his forces. This could not be carried out immediately, because the 16th Division remained engaged trying to extricate the pocketed 3rd Battalion, 20th Infantry. With further casualties, the remnants of the 3rd Battalion, 378 officers and men, were extricated on 15 February. On 22 February, the 14th Army line was withdrawn a few miles to the north, with USAFFE forces re-occupying positions evacuated by the Japanese.

Battle of the Points

In an attempt to outflank I Corps and isolate the service command area commanded by USAFFE deputy commander Brigadier General Allan C. McBride, Japanese troops of the 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry, 16th Division, were landed on the west coast of southern Bataan on the night of 22 January. Intercepted by U.S. PT-34, two barges were sunk and the rest scattered in two groups, neither of which landed on the objective beach. The Japanese forces were contained on their beachheads by members of Philippine constabulary units, a hastily organized naval infantry battalion, and by personnel of several U.S. Army Air Corps pursuit squadrons fighting as infantry, including Ed Dyess and Ray C. Hunt.[14][15]

The naval infantry consisted of 150 ground crewmen from Patrol Wing Ten, 80 sailors from the Cavite Naval Ammunition Depot, and 130 sailors from USS Canopus (AS-9), with 120 sailors from the base facilities at Cavite, Olongapo, and Mariveles, and 120 Marines from an antiaircraft battery. Sailors used the Canopus machine shop to fabricate makeshift mountings for machine guns salvaged from Patrol Wing Ten's damaged aircraft. The Marines were distributed through the ranks, and the sailors were told to "watch them and do as they do." The sailors attempted to make their white uniforms more suitable for jungle combat by dying them with coffee grounds. The result was closer to yellow than khaki, and the diary of a dead Japanese officer described them as a suicide squad dressed in brightly colored uniforms and talking loudly in an attempt to draw fire and reveal the enemy positions.[16]

Japanese commanders, in an attempt to hold onto their lodgements, reinforced the beachheads piecemeal, but could not break out. Battles were fought ferociously against a company-sized group at the Lapay-Longoskawayan points from 23 to 29 January, at the Quinawan-Aglaloma points from 22 January to 8 February, and at the Silalim-Anyasan points from 27 January to 13 February. Out of the 2,000 Japanese troops committed to these battles, only 43 wounded returned to their lines. These engagements were collectively termed the "Battle of the Points".

Fall of Bataan

On the night of 12 March, General MacArthur, his family, and several USAFFE staff officers left Corregidor for Mindanao aboard four PT boats commanded by Lieutenant Commander John D. Bulkeley. For this, and a number of other feats over the course of four months and eight days, Bulkeley was awarded the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Service Cross and other citations.

MacArthur was eventually flown to Australia where he broadcast to the Filipino people his famous "I Shall Return" promise. MacArthur's departure marked the end of the USAFFE, and by 22 March, the defending army was renamed the United States Forces in the Philippines (USFIP), and Lieutenant General Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright IV was placed in command.

After the failure of their first attack against Bataan, the Japanese general headquarters sent strong artillery forces to the Philippines in order to smash the American fortifications. They had 190 artillery pieces, which included bigger guns like 150 mm cannons and the rare Type 45 240 mm howitzer. The 1st Artillery headquarters, under Major General Kineo Kitajima, who was a known authority on IJA artillery, also moved to the Philippines along with the main forces to command and control these artillery units. Also, the Japanese high command reinforced General Homma's 14th Imperial Army, and toward the end of March, the Japanese forces prepared for the final assault.

On 3 April, the entire Orion-Bagac Line was subjected to incessant bombings by 100 aircraft and artillery bombardment by 300 artillery pieces from 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 pm, which turned the Mount Samat stronghold into an inferno. Over the course of the next three days (Good Friday to Easter Sunday, 1942), the Japanese 65th Brigade and 4th Division spearheaded the main attack at the left flank of II Corps. Everywhere along the line, the American and Filipino defenders were driven back by Japanese tanks and infantry.

Based on his two prior attempts, General Homma had estimated that the final offensive would require a week to breach the Orion-Bagac Line and a month to liquidate two final defense lines he believed had been prepared on Bataan. When the opening attack required just three days, he pushed his forces on 6 April to meet expected counterattacks head-on. The Japanese launched a drive into the center, penetrated into flanks held by the 22nd and 23rd Regiments of the 21st Division, captured Mount Samat and outflanked all of II Corps. Counterattacks by the U.S. Army and Philippine Scout regulars held in reserve were futile; only the 57th Infantry gained any ground, soon lost.

All along the battle front, units of I Corps, together with the devastated remnants of II Corps, crumbled and straggled to the rear. The commanders on Bataan lost all contact with their units, except by runner in a few instances. In the last two days of the defense of Bataan, the entire Allied defense progressively disintegrated and collapsed, clogging all roads with refugees and fleeing troops (some were evacuated by YAG-4 from the Mariveles Naval Base).[17] By 8 April, the senior U.S. commander on Bataan, Major General Edward P. King, saw the futility of further resistance, and put forth proposals for capitulation.

The next morning, 9 April 1942, General King met with Major General Kameichiro Nagano and, after several hours of negotiations, the remaining weary, starving and emaciated American and Filipino defenders on the battle-swept Bataan Peninsula surrendered.

Radio broadcast – Voice of Freedom – Malinta Tunnel – Corregidor – 9 April 1942:

Bataan has fallen. The Philippine-American troops on this war-ravaged and bloodstained peninsula have laid down their arms. With heads bloody but unbowed, they have yielded to the superior force and numbers of the enemy.

The world will long remember the epic struggle that Filipino and American soldiers put up in the jungle fastness and along the rugged coast of Bataan. They have stood up uncomplaining under the constant and grueling fire of the enemy for more than three months. Besieged on land and blockaded by sea, cut off from all sources of help in the Philippines and in America, the intrepid fighters have done all that human endurance could bear.

For what sustained them through all these months of incessant battle was a force that was more than merely physical. It was the force of an unconquerable faith—something in the heart and soul that physical hardship and adversity could not destroy. It was the thought of native land and all that it holds most dear, the thought of freedom and dignity and pride in these most priceless of all our human prerogatives.

The adversary, in the pride of his power and triumph, will credit our troops with nothing less than the courage and fortitude that his own troops have shown in battle. Our men have fought a brave and bitterly contested struggle. All the world will testify to the most superhuman endurance with which they stood up until the last in the face of overwhelming odds.

But the decision had to come. Men fighting under the banner of unshakable faith are made of something more than flesh, but they are not made of impervious steel. The flesh must yield at last, endurance melts away, and the end of the battle must come.

Bataan has fallen, but the spirit that made it stand—a beacon to all the liberty-loving peoples of the world—cannot fall![18]

Japanese tanks and infantry advance through the Bataan jungle.

Japanese tanks and infantry advance through the Bataan jungle. Fall of Bataan historical marker, Bataan, Capitolio

Fall of Bataan historical marker, Bataan, Capitolio MG Edward King discusses terms of surrender with Japanese officers.

MG Edward King discusses terms of surrender with Japanese officers.

Aftermath

The continued resistance of the force on Bataan after Singapore and the Indies had fallen made heartening news among the Allied peoples. However, the extension of time gained by the defence was very largely a result of the transfer of the 48th Division from Homma's army at a critical time, and the exhaustion of the weakened force that remained. It cost a far stronger Japanese army as many days of actual combat to take Malaya and Singapore Island as it cost Homma to take Bataan and Corregidor.[19]

The surrender of Bataan hastened the fall of Corregidor a month later. There is a suggestion that without the stand, the Japanese might have quickly overrun all of the U.S. bases in the Pacific and could have quickly invaded Australia.[20] Willoughby, MacArthur's Intelligence Officer, asserted after the war that the epic operation in Bataan and Corregidor became a decisive factor in the ultimate winning of the war, that it disrupted the Japanese timetable "in a way that was to prove crucial" and that "because of Bataan the Japanese never managed to detach enough men, planes, ships, and material to nail down Guadalcanal." Rather than allowing the operations on Luzon to upset their general timetable, the Japanese took steps that resulted in prolonging the resistance of Luzon in order to speed up their conquest of the Indies. Between the time of their advance into the Solomons and the American counter-landing on Guadalcanal in August, three months after the fall of Corregidor, they had ample troops available to build up their strength in the South Seas.[19]

However, historian Teodoro Agoncillo argues that the battle was "unnecessary in so far as the throwing away of precious lives was concerned, for it served no strategic purpose." It was only Yamashita who thought of invading Australia, something that Tojo did not support. Finally, not only did the USAFFE possess numerical superiority, it could have recaptured Manila easily (according to Homma).[21]

Ultimately, more than 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war were forced into the Bataan Death March.[5] However, about 10,000–12,000 of these eventually escaped from the march to form guerrilla units in the mountains, tying down the occupying Japanese. On 7 September 1944, the Japanese ship Shinyō Maru was sunk by USS Paddle; on board the Shinyo Maru were U.S. POWs, of whom 668 died and 82 survived.

After more than two years of fighting in the Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur initiated the Campaign for the Liberation of the Philippines, fulfilling his promise to return to the country he had left in 1942. As part of the campaign, the Battle for the recapture of Bataan (31 January to 21 February 1945) by Allied forces and Philippine guerrillas avenged the surrender of the defunct United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) to invading Japanese forces.

Legacy

Araw ng Kagitingan (Day of Valour), 9 April, the day Bataan fell into Japanese hands, was declared a national holiday in the Philippines.[22] Previously called Bataan Day, the day is now known as Araw ng Kagitingan or Day of Valour, commemorating both the Fall of Bataan (9 April 1942) and the Fall of Corregidor (6 May 1942).

The Dambana ng Kagitingan (Shrine of Valor) is a memorial shrine erected on top of Mount Samat in Pilar, Bataan, in the Philippines. The war memorial grounds feature a colonnade that houses an altar, esplanade, and a museum. On the peak of the mountain is the memorial cross standing about 311 ft (95 m) high.

USS Bataan (LHD-5), commissioned on 20 September 1997, the United States Navy Wasp class amphibious assault ship commemorates "those who served and sacrificed in the Philippines in the name of freedom in the Pacific".

USS Bataan (CVL-29), commissioned on 17 November 1943, the United States Navy Independence class aircraft carrier commemorated "those who served and sacrificed in the Philippines in the name of freedom in the Pacific" until her decommissioning on 9 April 1954.

The Bataan Death March Memorial Monument, erected in April, 2001, is the only monument funded by the U.S. federal government dedicated to the victims of the Bataan Death March during World War II. The memorial was designed and sculpted by Las Cruces artist Kelley Hester and is located in Veterans Park along Roadrunner Parkway in New Mexico.[23]

Bataan-Corregidor Memorial Bridge is a bascule bridge on State Street in Chicago, Illinois, where it crosses the Chicago River. It was built in 1949 and rededicated on 9 April 1998, commemorating not only the Day of Valour but also the centennial of the declaration of Philippine independence from Spain in 1898.[24][25]

Mariveles, Bataan Memorial Shrine (Km. Zero, starting point of Death March, 9–17 April 1942)

Mariveles, Bataan Memorial Shrine (Km. Zero, starting point of Death March, 9–17 April 1942)_conducts_flight_operations_underway_in_the_Atlantic_Ocean.jpg.webp)

A U.S. Army member posts the flag of the "Battling Bastards of Bataan" at the opening ceremony of the Bataan Memorial Death March.

A U.S. Army member posts the flag of the "Battling Bastards of Bataan" at the opening ceremony of the Bataan Memorial Death March.

In film, television and song

Among the many films and television programs that feature the story of Bataan are Bataan (1943) starring Robert Taylor, the John Ford classic They Were Expendable (1945), starring Robert Montgomery, John Wayne, and Donna Reed, Back to Bataan (1945) starring Wayne and Anthony Quinn, and two movies about the nurses of Bataan: So Proudly We Hail! (1943) and Cry 'Havoc' (1943).

Dozens of documentaries have also featured stories from the Battle of Bataan including A Legacy of Heroes: The Story of Bataan and Corregidor (2003), Ghosts of Bataan (2005) and an episode of The History Channel series Shootout, entitled "Raid on the Bataan Death Camp" (2006). Though largely focusing on the Cabanatuan Raid in 1945, this last program also featured stories from the 1942 battle; notably the stand of the 57th Infantry Regiment (PS) at Mabatang.

The Battle of Bataan is referenced among important battles of American history in the song The House I Live In, sang by Frank Sinatra in the film of the same name and later taken up by Paul Robeson and various other singers: "The little bridge at Concord, where Freedom’s fight began, / Our Gettysburg and Midway, and the story of Bataan".

See also

- Angels of Bataan

- Frank Adamo – called by Life magazine "Bataan's medical hero"

- Wenceslao Vinzons – Filipino guerrilla leader who resisted until July 8, 1944.

References

- "The Philippines (Bataan) (1942)". The War. WETA. 2005.

The 76,000 prisoners of war of the battle for Bataan – some 64,000 Filipino soldiers and 12,000 U.S. soldiers – then were forced to endure what came to be known as the Bataan Death March as they were moved into captivity.

Elizabeth M. Norman; Michael Norman (6 March 2017). "Bataan Death March". Encyclopædia Britannica.Bataan Death March, march in the Philippines of some 66 miles (106 km) that 76,000 prisoners of war (66,000 Filipinos, 10,000 U.S.) were forced by the Japanese military to endure in April 1942, during the early stages of World War II.

Roy C. Mabasa (9 April 2017). "U.S. salutes Filipino vets". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

Eric Morris (5 September 2000). Corregidor: The American Alamo of World War II. Cooper Square Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-4616-6092-7.

Oliver L. North (28 March 2012). War Stories II: Heroism in the Pacific. Regnery Publishing. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-59698-305-2. - Senshi Sōsho (戦史叢書) (in Japanese). 2. Asagumo Shimbunsha. 1966.

- Irvin Alexander (April 2005). Surviving Bataan and Beyond: Colonel Irvin Alexander's Odyssey as a Japanese Prisoner of War. Stackpole Books. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-8117-3248-2.

Yuma Totani (16 February 2015). Justice in Asia and the Pacific Region, 1945-1952. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-107-08762-0. - Robertson, p. 606.

- William L. O'Neill, A Democracy at War: America's Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II, p 115 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- cite: Jerry Kruth researching "The Bamboo Soldiers."

- Morton, Louis (1953). The Fall of the Philippines. US Army Center of Military History.

- Murphy, Kevin C. (2014). Inside the Bataan Death March: Defeat, Travail and Memory. McFarland. p. 328. ISBN 978-0786496815.

- Louis Morton. "The Decision To Withdraw to Bataan". U.S. Army Center of Military History. United States Army. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Herman, Arthur (2016). Douglas McArthur: American Warrior. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0812994896. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Darman, Peter (2012). Attack on Pearl Harbor: America Enters World War II. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1448892334.

- None More Courageous – American War Heroes of Today, Stewart H. Holbrook, March 2007, ISBN 9781406741193, retrieved 14 January 2010

- https://www.army.mil/medalofhonor/keeble/medal/citations20.htm#B

- Dyess, W.E., 1944, The Dyess Story, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons

- Hunt, Ray C., and Norling, Bernard, 1986, Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerrilla in the Philippines, The University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0-8131-1604-X

- Gordon, John IV, Capt. USA "The Navy's Infantry at Bataan" United States Naval Institute Proceedings Supplement March 1985 pp.64–69

- Radigan, Joseph M. "Service Ship Photo Archive YAG-4". NavSource – Naval Source History. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- College Writing and Reading. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-971-23-0571-9.

- (Long G, "MacArthur as Military Commander" (1969), Angus and Robertson (Australia), p.83.)

- William L. O'Neill, A Democracy at War: America's Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II, p 116 ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- A., Agoncillo, Teodoro (2001). The fateful years : Japan's adventure in the Philippines, 1941–45 (2001 ed.). Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. pp. 851, 853. ISBN 9715422748. OCLC 48220661.

- "Republic Act no. 9188". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved on 2011-03-22.

- Bataan "Bataan Death March Memorial" Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Las Cruces Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved on 2011-03-20.

- "Commemorative plaque". Historic Bridges.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-21.

- "Photo – Memorial Plate". Historic Bridges.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-21.

Sources

- Robertson, Jr, James I. (1997). Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Bartsch, William H. (2003). 8 December 1941: MacArthur's Pearl Harbor. College Station, TX, USA: Texas A&M University Press.

- Burton, John (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-096-X.

- Connaughton, Richard (2001). MacArthur and Defeat in the Philippines. New York: The Overlook Press.

- Mallonee, Richard C. (2003). Battle for Bataan : An Eyewitness Account. I Books. ISBN 0-7434-7450-3.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: Conquest of the Pacific 1941–42. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-789-5.

- Whitman, John W. (1990). Bataan: Our Last Ditch : The Bataan Campaign, 1942. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-87052-877-7.

- Young, Donald J. (1992). The Battle of Bataan: A History of the 90 Day Siege and Eventual Surrender of 75,000 Filipino and United States Troops to the Japanese in World War. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-89950-757-3.

Further reading

- Morton, Louis (2000) [1960]. "Chapter 6: The Decision to Withdraw to Bataan". In Kent Roberts Greenfield (ed.). Command Decisions (reissue). United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7.

- Morton, Louis (1953). The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Bataan. |

- "Marines in the Defense of the Philippines" Photos and Text

- World War II Medal of Honor Recipients A-F at the United States Army Center of Military History

- World War II Medal of Honor Recipients M-S at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Animated History of The Battle of Bataan and Corregidor

- Battle for Bataan

- Info on the Dambana ng Kagitingan Shrine (archived from the original on 13 July 2007).

- Back to Bataan a survivor's story

- History of Provisional Tank Group before, during and after the Battle of Bataan