Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (Italian: [franˈtʃesko ɡwittʃarˈdiːni]; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his masterpiece, The History of Italy, Guicciardini paved the way for a new style in historiography with his use of government sources to support arguments and the realistic analysis of the people and events of his time.

Francesco Guicciardini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 March 1483 |

| Died | 22 May 1540 (aged 57) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Historian, statesman |

Biography

Early life

Francesco Guicciardini was born 6 March 1483 in Florence, now in Italy; he was the third of eleven children of Piero di Iacopo Guicciardini and Simona di Bongianni Gianfigliazzi. The Guicciardini were well-established members of the Florentine oligarchy as well as supporters of the Medici. Influential in Florentine politics, Guicciardini's ancestors had held the highest posts of honor in the state for many generations, as may be seen in his own genealogical Ricordi autobiografici e di famiglia.[1]

Piero Guicciardini had studied with the philosopher Marsilio Ficino, who stood as his son's godfather. Like his father, Francesco received a fine humanist education and studied the classics, learning both Latin and a little Greek.[2] The boy was sent by his father to study law at the Universities of Ferrara and Padua, where he stayed until the year 1505.[3]

The death of an uncle, who had occupied the see of Cortona, induced the young Guicciardini to seek an ecclesiastical career. His father, however, "thought the affairs of the Church were decadent. He preferred to lose great present profits and the chance of making one of his sons a great man rather than have it on his conscience that he had made one of his sons a priest out of greed for wealth or great position."[4] Thus, the ambitious Guicciardini once again turned his attention to law. At 23, he was appointed by the Signoria of Florence to teach legal studies at the Florentine Studio.

In 1508, he married Maria Salviati, the daughter of Alamanno Salviati, cementing an oligarchical alliance with the powerful Florentine family. In the same year, he wrote the Memorie di famiglia, a family memoir of the Guicciardini family, the Storie Fiorentine (Tales of Florence), and began his Ricordi, a rudimentary personal chronicle of his life.[5]

Spanish court

Having distinguished himself in the practice of law, Guicciardini was entrusted by the Florentine Signoria with an embassy to the court of the King of Aragon, Ferdinand the Catholic, in 1512. He had doubts about accepting the position because it came with so little profit and would disrupt his law practice and take him away from the city. However, Francesco's father convinced him of the court’s prestige and the honour of having been chosen at so young an age. "No one could remember at Florence that such a young man had ever been chosen for such an embassy", he wrote in his diary.[6] Thus Guicciardini started his career as a diplomat and statesman.

His Spanish correspondence with the Signoria[7] reveals his power of observation and analysis, a chief quality of his mind. At the Spanish court, he learned lessons of political realism. In his letters back home, he expressed appreciation for being able to observe Spanish military methods and estimate their strength during the time of war. However, he also distrusted the calculated gestures of Ferdinand and referred to him as a model of the art of political deceit. During his time in Spain, the Medici regained power in Florence. Under the new regime, his embassy in Spain dragged on, frustrating Guicciardini as he yearned to return to Florence and participate in its political life. Guicciardini insisted on being recalled and even sent a letter to the youthful Lorenzo de’ Medici in an attempt to secure a position in the new ruling group.[8] Guicciardini eventually returned home to Florence, where he took up his law practice again; in 1514, he served as a member of the Otto di Balìa, who controlled internal security, and in 1515, he served on the Signoria, the highest Florentine magistracy.[9]

Papacy

In 1513, Giovanni de' Medici, the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, became Pope Leo X and brought Florence under papal control, which provided opportunities for Florentines to enter papal service, as did Francesco in 1515. Leo X made him governor of Reggio in 1516 and Modena in 1517. This was the beginning of a long career for Guicciardini in papal administration, first under Leo X and then under his successor, Clement VII.[6] "He governed Modena and Reggio with conspicuous success" according to The Catholic Encyclopedia. He was appointed to govern Parma, and according to the Encyclopedia, "in the confusion that followed the pope's death, he distinguished himself by his defence of Parma against the French (1521)."[10]

In 1523, he was appointed viceregent of the Romagna by Clement VII (1478-1534). These high offices rendered Guicciardini the virtual master of the Papal States beyond the Apennine Mountains. As he later described himself during this period: "If you had seen messer Francesco in the Romagna...with his house full of tapestries, silver, servants thronged from the entire province where—since everything was completely referred to him—no one, from the Pope down, recognized anyone as his superior...".[11]

The political turmoil in Italy was continuously intensifying. As hostilities between King Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, escalated, the Pope remained undecided over which side to back and so sought Guicciardini's advice. Guicciardini advised an alliance with France and urged Clement to conclude the League of Cognac in 1526, which led to war with Charles V. Later that year, as the forces of Charles V threatened to attack, Clement made Guicciardini lieutenant-general of the papal army. Guicciardini was powerless to influence the commander of papal forces, Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, to take action.

However, in April 1527, Guicciardini succeeded in averting an attack on Florence from a rebellious imperial army, which turned toward Rome instead.[12] Less than two weeks later came the news of the Sack of Rome and the imprisonment of Clement in the Castel Sant'Angelo.

Guicciardini served three popes over a period of twenty years, and perhaps because of his experiences, he was highly critical of the papacy: "I don't know anyone who dislikes the ambition, the avarice, and the sensuality of priests more than I do.... Nevertheless, the position I have enjoyed with several popes has forced me to love their greatness for my own self-interest. If it weren't for this consideration, I would have loved Martin Luther as much as I love myself—not to be released from the laws taught by the Christian religion as it is normally interpreted and understood, but to see this band of ruffians reduced within their correct bounds."[13]

Florentine Republic

Like many Florentine aristocrats of his day, Guicciardini believed in a mixed republican government based on the model of the Venetian constitution;[14] despite working so often and closely with the Medici, he viewed their rule as tyrannical.[15] Guicciardini was still able to reconcile his republican ideals and his support of the Medici: "The equality of men under a popular government is by no means contradicted if one citizen enjoys greater reputation than another, provided it proceed from the love and reverence of all, and can be withheld by the people at their pleasure. Indeed, without such supports, republics can hardly last."[16]

Shortly after the Sack of Rome, Guicciardini returned to Florence, but by 1527, the Medici had been expelled from the city, and a republic had been re-established by the extreme anti-Medici Arrabiati faction. Because of his close ties to the Medici, Guicciardini was held suspect in his native city.

In March 1530, as a result of his service to the Medici, Guicciardini was declared a rebel and had his property confiscated.[17]

This final Florentine Republic did not last long, however, and after enduring the Siege of Florence by imperial troops for nine months, in 1530 the city capitulated. Under the command of Clement VII, Guicciardini was assigned the task of punishing the Florentine citizens for their resistance to the Medici, and he dealt out justice mercilessly to those who had opposed the will of the Pope.[18] Benedetto Varchi claimed that in carrying out his task, "Messer Francesco Guicciardini was more cruel and more ferocious than the others".[19]

Final years

In 1531, Guicciardini was assigned the governorship of Bologna, the most important city in the northern Papal States by Clement VII.[20] Guicciardini resigned after Clement's death in 1534 and returned to Florence, where he was enlisted as advisor to Alessandro de Medici, “whose position as duke had become less secure following the death of the pope”.[18] Guiccardini defended him in Naples in 1535 before Charles V, contesting the exiled rebels' accusations of tyranny.[21] He assisted in successfully negotiating the marriage of Alessandro to the emperor Charles V’s daughter Margaret of Parma in 1536, and for a short time Gucciardini was the most trusted advisor to Alessandro until the Duke's assassination in 1537.

Then, Guicciardini allied himself with Cosimo de' Medici, who was just 17 and new to the Florentine political system. Guicciardini supported Cosimo as duke of Florence; nevertheless, Cosimo dismissed him shortly after rising to power. Guicciardini retired to his villa in Arcetri, where he spent his last years working on the Storia d'Italia. He died in 1540 without male heirs.[9]

His nephew, Lodovico Guicciardini, was also a historian known for his 16th-century works on the Low Countries.

Works

None of Francesco Guicciardini's works were published during his lifetime. It was not until 1561 that the first sixteen of the twenty books of his History of Italy were published. The first English "translation" by Sir Geffray Fenton was published in 1579.[22] Until 1857, only the History and a small number of extracts from his aphorisms were known. In that year, his descendants opened the Guicciardini family archives and committed to Giuseppe Canestrini the publication of his memoirs in ten volumes.[23] These are some of his works recovered from the archives:

- Ricordi politici e civili, already noted, consisting of about 220 maxims on political, social, and religious topics;

- Observations on Machiavelli's Discorsi, which bring into relief the views of Italy's two great theorists on statecraft in the 16th century, and show that Guicciardini regarded Machiavelli somewhat as an amiable visionary or political enthusiast;

- Storia Fiorentina, an early work of the author, distinguished by its animation of style, brilliancy of portraiture and liberality of judgment;

- Dialogo del reggimento di Firenze, also in all probability an early work, in which the various forms of government suited to an Italian commonwealth are discussed with subtlety, contrasted and illustrated from the vicissitudes of Florence up to the year 1494.

- There is also a series of short essays, entitled Discorsi politici, composed during Guicciardini's Spanish legation.

Taken in combination with Machiavelli's treatises, the Opere inedite offer a comprehensive body of Italian political philosophy before Paolo Sarpi.

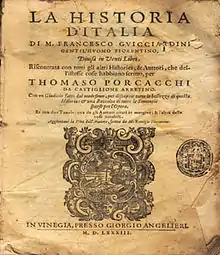

The History of Italy

Guicciardini is best known as the author of the Storia d'Italia (History of Italy), which provides a detailed account of politics in the Italian Peninsula between 1490 and 1534. Written during the last years of his life, this work contains the historian's observations collected over his entire lifetime and was a work intended for posterity. As Gilbert writes: "The History of Italy stands apart from all his writings because it was the one work which he wrote not for himself, but for the public."[24]

In his research, Guicciardini drew upon material that he gathered from government records as well as from his own extensive experience in politics. His many personal encounters with powerful Italian rulers serves to explain his perspective as a historian: “Francesco Guicciardini might be called a psychological historian—for him the motive power of the huge clockwork of events may be traced down the mainspring of individual behavior. Not any individual, be it noted, but those in positions of command: emperors, princes and popes who may be counted on to act always in terms of their self-interest—the famous Guicciardinian particolare.”[25] In the following excerpt, the historian records his observations on the character of Pope Clement VII:

“And although he had a most capable intelligence and marvelous knowledge of world affairs, yet he lacked the corresponding resolution and execution. For he was impeded not only by his timidity of spirit, which was by no means small, and by a strong reluctance to spend, but also by a certain innate irresolution and perplexity, so that he remained almost always in suspension and ambiguous when he was faced with those deciding those thing which from afar he had many times foreseen, considered, and almost revealed."[26]

Moreover, what sets Guicciardini apart from other historians of his time is his understanding of historical context. His approach was already evident in his early work The History of Florence (1509): “The young historian was already doubtlessly aware of the meaning of historical perspective; the same facts acquiring different weight in different contexts, a sense of proportion was called for.”[27]

In the words of one of Guicciardini's severest critics, Francesco de Sanctis: "If we consider intellectual power [the Storia d'Italia] is the most important work that has issued from an Italian mind."[28]

Guicciardini and Machiavelli on politics and history

Guicciardini was friends with Niccolò Machiavelli; the two maintained a lively correspondence until the latter's death in 1527. Guicciardini was on a somewhat higher social standing than his friend, but through their letters, a relaxed, comfortable relationship between the two emerges. "Aware of their difference in class, Machiavelli nevertheless was not intimidated by Guicciardini's offices... or by his aristocratic connections. The two established their rapport because of mutual regard for each other's intellect."[29] They discussed personal matters and political ideas and influenced each other's work.

Guicciardini was critical of some of the ideas expressed by Machiavelli in his Discourses on Livy, "Guicciardini's principal objection to the theories which Machiavelli advanced in the Discourses was that Machiavelli put things 'too absolutely.' Guicciardini did not agree with Machiavelli's basic assumption that Rome could serve as a perfect norm."[30]

Both were innovative in their approach to history: "Machiavelli and Guicciardini are important transitional figures in the development of historical writing. The historical consciousness that becomes visible in their work is a significant rupture in our thinking about the past... Human agency was a central element in the historical thought of Machiavelli and Guicciardini, but they did not have a modern notion of individuality.... They started to disentangle historiography from its rhetorical framework, and in Guicciardini’s work we can observe the first traces of a critical historical method."[31]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francesco Guicciardini. |

The following list contains alternative names used for his works in Italian and English:

- Storie fiorentine (History of Florence 1509)

- Diario di viaggio in Spagna (1512)

- Discorso di Logrogno ("Discourse of Logrogno"; 1512)

- Relazione di Spagna (1514)

- Consolatoria (1527)

- Oratio accusatoria (1527)

- Oratio defensoria (1527)

- Del reggimento di Firenze or Dialogo e discorsi del reggimento di Firenze ("Dialogue on Florentine Government" or "Dialogue on the Government of Florence"; 1527)

- Considerazioni intorno ai "Discorsi" del Machiavelli sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio ("Observations on Machiavelli's Discourses"; 1528, or possibly 1530[6])

- Ricordi or Ricordi civili e politici (the name given by Giuseppe Canestrini when he first published the book in 1857) or Ricordi politici e civili (as the Catholic Encyclopedia refers to it); in English, usually "the Ricordi" but called "Maxims and Reflections (Ricordi)" in one translation and "Counsels and Reflections" in another (1512–1530).[32]

- Le cose fiorentine (second "History of Florence"; 1528–1531)

- Storia d'Italia ("History of Italy"; 1537–1540)

Further reading

- Knutsen, Torbjørn L. 2020. "Renaissance politics." in A history of International Relations theory (third edition). Manchester University Press.

Notes

- Op. med. vol. X.

- Alison Brown, Introduction to Francesco Guicciardini, Dialogue on the Government of Florence (Cambridge: 1994), p.vii

- "Francesco Guicciardini" in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 61 (2004)

- Guicciardini Ricordi, Trans. by Margaret Grayson in Cecil Grayson, ed. Francesco Guicciardini, Selected Writings, (London: 1965), p. 132

- Mark Phillips, Francesco Guicciardini: The Historian's Craft, (Toronto, 1977).

- Guicciardini, Francesco. Scritti autobiografici e rari, (his diary), ed. R. Palmarocchi (Bari: 1936) p. 69, as quoted and footnoted in Guicciardini, Francesco, Maxims and Reflections (Ricordi) (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1972) Paperback ISBN 0-8122-1037-9 "Introduction", by Nicolai Rubinstein, p. 7

- Op. med., Volume VI

- Mark Phillips, Francesco Guicciardini: The Historian's Craft, (Toronto: 1977)

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Guicciardini, Francesco". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Guicciardini, Francesco". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Sydney Alexander, Introduction to Francesco Guicciardini, The History of Italy, (Princeton, 1969), p. xvii.

- Nicolai Rubinstein, The Storie Fiorentine and the Memorie di Famiglia by Francesco Guicciardini(Firenze: 1953)

- Francesco Guicciardini, Maxim 28, in Alison Brown (trans.), Guicciardini: Dialogue on the Government of Florence (Cambridge, 1994), p.171.

- Gilbert, op. cit. p.103

- Op. med. I. 171, on the tyrant; the whole Storia Fiorentina and Reggimento di Firenze, lb. i. and iii., on the Medici

- Francesco Guicciardini, Maxims and Reflections (Ricordi), Mario Domandi, trans., Introd. by Nicolai Rubinstein, (New York, Harper & Row, 1965) p.144

- The History of Italy

- Grendler, Paul F. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Renaissance (New York: Scribner’s Sons).

- Benedetto Varchi, Storia Fiorentina

- Correspondence, Op. med. vol. IX.

- Op. med. Volume IX

- Sydney Alexander, op. cit. p. xxv.

- Opere Inedite di Francesco Guicciardini (Firenze, 1857-1867)

- Felix Gilbert, Machiavelli and Guicciardini: Politics and History in Sixteenth-Century Florence (Princeton, 1985)

- Sidney Alexander, Introduction to Francesco Guicciardini, The History of Italy, (Princeton, 1969), p.xv.

- Francesco Guicciardini The History of Italy, translated and edited by Sydney Alexander, (Princeton, 1969), p.363

- Nicolai Rubinstein, The Storie Fiorentine and the Memorie di famiglia by Francesco Guicciardini 6th ed. vol. 5. (Sansoni, Firenze, 1953)

- Sidney Alexander, Introduction to Francesco Guicciardini, The History of Italy (Princeton: 1969), p.xv.

- Machiavelli and His Friends: Their Personal Correspondence, James B. Atkinson and Davis Sices, Trans. and Ed. (Northern Illinois Press: 2004) pp. xx-xxi

- Felix Gilbert, Machiavelli and Guicciardini, p. 283

- Bod, Maat, & Weststeijn, The Making of the Humanities: Vol. 1 Early Modern Europe, (Amsterdam: 2010), p.362

- Guicciardini, Francesco (1965). Maxims and Reflections of a Renaissance Statesman (Ricordi); Introduction by Nicolai Rubinstein. Translated by Domandi, Mario. New York, Evanston and London: Harper Torchbooks. Retrieved December 19, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Francesco Guicciardini |

- Works by or about Francesco Guicciardini at Internet Archive

- Works by Francesco Guiccardini at Project Liberliber.it

- Works by or about Francesco Guicciardini in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Guicciardini: all the texts

- La Historia d'Italia : Nuouamente con somma diligenza ristampata, et da molti errori ricorretta. Con l'aggiunta de' sommarii à libro per libro et con le annotationi in margine delle cose piu notabili fatte dal reuerendo padre Remigio fiorentino. Oue s'è messa ancora una copiosissima Tauola per maggior commodità de' Lettori. Venezia : Appresso Nicolò Beuilacqua, 1563. 990 p. - available online at University Library in Bratislava Digital Library