John of Salisbury

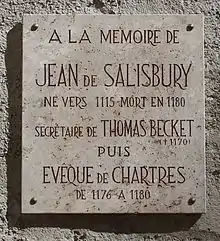

John of Salisbury (late 1110s – 25 October 1180), who described himself as Johannes Parvus ("John the Little"),[1] was an English author, philosopher, educationalist, diplomat and bishop of Chartres, and was born at Salisbury, England.

Early life and education

He was of Anglo-Saxon, not of Norman extraction, and therefore apparently a clerk from a modest background, whose career depended upon his education. Beyond that, and that he applied to himself the cognomen of Parvus, "short", or "small", few details are known regarding his early life. From his own statements it is gathered that he crossed to France about 1136, and began regular studies in Paris under Peter Abelard,[2] who had for a brief period re-opened his famous school there on Montagne Sainte-Geneviève.

His vivid accounts of teachers and students provide some of the most valuable insights into the early days of the University of Paris.[3] When Abelard withdrew from Paris John studied under Master Alberic and Robert of Melun. In 1137 John went to Chartres, where he studied grammar under William of Conches, and rhetoric, logic and the classics under Richard l'Evêque, a disciple of Bernard of Chartres.[4] Bernard's teaching was distinguished partly by its pronounced Platonic tendency, and partly by the stress laid upon literary study of the greater Latin writers. The influence of the latter feature is noticeable in all John of Salisbury's works.

Around 1140 John returned to Paris to study theology under Gilbert de la Porrée, then under Robert Pullus and Simon of Poissy, supporting himself as a tutor to young noblemen. In 1148 he resided at the Abbey of Moutiers-la-Celle in the diocese of Troyes, with his friend Peter of Celle. He was present at the Council of Reims in 1148, presided over by Pope Eugene III. It is conjectured that while there, he was introduced by St. Bernard of Clairvaux to Theobald, whose secretary he became.[2]

Secretary to the Archbishop of Canterbury

John of Salisbury was secretary to Archbishop Theobald for seven years. While at Canterbury he became acquainted with Thomas Becket, one of the significant potent influences in John's life. During this period he went on many missions to the Papal See; it was probably on one of these that he made the acquaintance of Nicholas Breakspear, who in 1154 became Pope Adrian IV. The following year John visited him, remaining at Benevento with him for several months. He was at the court of Rome at least twice afterward.[4]

During this time he composed his greatest works, published almost certainly in 1159, the Policraticus, sive de nugis curialium et de vestigiis philosophorum and the Metalogicon, writings invaluable as storehouses of information regarding the matter and form of scholastic education, and remarkable for their cultivated style and humanist tendency. The Policraticus also sheds light on the decadence of the 12th-century court manners and the lax ethics of royalty. The idea of contemporaries standing on the shoulders of giants of Antiquity first appears in written form in the Metalogicon. After the death of Theobald in 1161, John continued as secretary to his successor, Thomas Becket, and took an active part in the long disputes between that primate and his sovereign, Henry II, who looked upon John as a papal agent.[5]

His letters throw light on the constitutional struggle then agitating England. In 1163, John fell into disfavor with the king for reasons that remain obscure, and withdrew to France. The next six years he spent with his friend Peter of La Celle, now Abbot of St. Remigius at Reims. Here he wrote "Historia Pontificalis".[6] In 1170 he led the delegation charged with preparing for Becket's return to England,[2] and was in Canterbury at the time of Becket's assassination. In 1174 John became treasurer of Exeter cathedral.

Bishop of Chartres

In 1176 he was made bishop of Chartres, where he passed the remainder of his life. In 1179 he took an active part in the Third Council of the Lateran. He died at or near Chartres on October 25, 1180.[1]

Scholarship and influences

John's writings are excellent at clarifying the literary and scientific position of 12th century Western Europe. Though he was well versed in the new logic and dialectical rhetoric of the university, John's views imply a cultivated intelligence well versed in practical affairs, opposing to the extremes of both nominalism and realism a practical common sense. His doctrine draws on the literary scepticism of Cicero, for whom he had unbounded admiration and on whose style he based his own. His view that the end of education was moral, rather than merely intellectual, became one of the prime educational doctrines of western civilization. This moral vision of education shares more in common with the tradition of monastic education which preceded his own Scholastic age, and with the vision of education which re-emerges in the world-view of Renaissance humanism.[7]

Of Greek writers he appears to have known nothing at first hand, and very little in translations. He was one of the best Latinists of his age. The Timaeus of Plato in the Latin version of Chalcidius was known to him as to his contemporaries and predecessors, and probably he had access to translations of the Phaedo and Meno. Of Aristotle he possessed the whole of the Organon in Latin; he is, indeed, the first of the medieval writers of note to whom the whole was known.

He first coined the term theatrum mundi, a notion that influences the theater several centuries later. In several chapters of the third book of his Policraticus, he meditates on the fact that "the life of man on earth is a comedy, where each forgetting his own plays another's role".[8]

Fictional portrayals

John was portrayed by actor Alex G. Hunter in the 1924 silent film Becket, based on the play of the same title by Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Works

- Latin text

- John of Salisbury (1639) [1159]. Policraticus: sive de nugis curialium et vestigiis philosophorum, libri octo accedit huic editioni ejusdem metalogicus (in Latin). Lugduni Batavorum: ex officina Ioannis Maire.

- Metalogicon, edited by J.B. Hall & Katharine S.B. Keats-Rohan, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis (CCCM 98), Turnhout, Brepols 1991.

- Latin text and English translations

- Anselm & Becket. Two Canterbury Saints' Lives by John of Salisbury, Ronald E. Pepin (transl.) Turnhout, 2009, Brepols Publishers,ISBN 978-0-88844-298-7

- The Letters of John of Salisbury, 2 vols., ed. and trans. W. J. Millor and H. E. Butler (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979–86)

- Historia Pontificalis, ed. and trans. Marjorie Chibnall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986)

- John of Salisbury's Entheticus maior and minor, ed. and trans. Jan van Laarhoven [Studien und Texte zur Geistesgeschichte des Mittelalters 17] (Leiden: Brill, 1987)

- English translations

- John of Salisbury (1990) [1159]. Nederman, Cary J (ed.). Policraticus, sive de nugis curialium et de vestigiis philosophorum [Policraticus: Of the frivolities of courtiers and the footprints of philosophers]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36399-3. (full text on Internet Archive) somewhat abridged

- — (1938) [1159]. Pike, Joseph B (ed.). Frivolities of courtiers and footprints of philosophers: being a translation of the first, second, and third books and selections from the seventh and eighth books of the Policraticus of John of Salisbury. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press. (full text on Internet Archive)

- The statesman’s book of John of Salisbury; being the fourth, fifth, and sixth books, and selections from the seventh and eighth books, of the Policraticus, trans. John Dickinson (New York: Knopf, 1927)

- The Metalogicon, A Twelfth-Century Defense of the Verbal and Logical Arts of the Trivium, trans. Daniel McGarry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1955)

- Metalogicon, translated by J.B. Hall, Corpus Christianorum in Translation (CCT 12), Turnhout, Brepols, 2013.

- Studies

- A Companion to John of Salisbury, ed. Christophe Grellard and Frédérique Lachaud, Leiden, Brill, Brill's Companions to the Christian Tradition, 57, 2014 (copyright 2015), 480 p. (ISBN 9789004265103)

- Michael Wilks (ed.), The World of John of Salisbury, Oxford, Blackwell, 1997.

- John D. Hosler, John of Salisbury: Military Authority of the Twelfth-Century Renaissance, Leiden, Brill, 2013, 240 p. (ISBN 9789004226630)

- English excerpts of John's political theory

References

- McCormick, Stephen J. (1889). The Pope and Ireland. San Francisco: A. Waldteufel. pp. 44.

- Guilfoy, Kevin, "John of Salisbury", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Cantor 1992:324.

- John of Salisbury. Frivolities of Courtiers and Footprints of Philosophers, (Joseph B. Pike, trans.), University of Minnesota, 1938

- Norman F. Cantor, 1993. The Civilization of the Middle Ages, 324-26.

- Coffey, Peter. "John of Salisbury." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 20 Jul. 2015

- Cantor 1993:325f.

- John Gillies, Shakespeare and the Geography of Difference, Volume 4 of Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 9780521458535. Pages 76-77.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John of Salisbury |

- Bollermann, Karen; Nederman, Cary. "John of Salisbury". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "John of Salisbury". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "John of Salisbury". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Lane-Poole, Reginald (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 29. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Coffey, Peter (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Luscombe, David. "Salisbury, John of (late 1110s–1180)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14849. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)