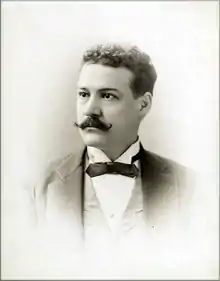

Francis Richter

Francis Charles Richter (January 26, 1854 – February 12, 1926) was an American journalist who served as founder and editor of Sporting Life from its inception to its demise, and editor of the Reach Guide from its inception in 1901. Richter died the day after completing the 1926 edition of the Reach Guide. As a writer and associate of baseball officials, he was influential in the early development of the game.

Francis C. Richter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 26, 1854 Philadelphia |

| Died | February 12, 1926 (aged 72) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Journalist, Editor |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | News Paper Journalism |

| Subject | Sports |

| Notable works | History and Records of Baseball, Sporting Life |

| Notable awards | Honor Rolls of Baseball |

Biography

Born in Philadelphia, Richter was a journalist from his youth. His early career as an amateur baseball player was an invaluable tool, which provided him with a rich supply of insight into the game and players' lives (Reach Guide, 1926).

In 1872 he began his career with the Philadelphia Day, and when that paper folded eight years later, he had established his reputation as a successful managing editor in the journalistic world. He began writing for the Sunday World and started the nation's first newspaper sports department of the era while working at the Public Ledger. Richter helped form the original American Association of baseball in 1882 and to place the Philadelphia Athletics in it. The next year, becoming disgusted with the "Beer and Whiskey League" and its Sunday baseball, he helped organize the Philadelphia Phillies in the National League.

In 1883 Richter founded the Sporting Life, a weekly magazine devoted to coverage of all sports, with an emphasis on baseball. Richter hired correspondents from around the country. He was the first editor of the journal, which became the mouthpiece of baseball and a great force in the national pastime. Within a year circulation had grown to 20,000, and by 1886 it was at 40,000. Initially each issue had 16 pages and sold for ten cents.

On December 12, 1887, Richter and other baseball journalists formed the Base Ball Reporters Association of America, also referred to as the National Base Ball Reporters' Association, at Cincinnati.

In 1902 Richter jumped ship to join with the American League's founders. He was a World Series official for many years, and wrote a history of baseball.

He warned of the potential problems of corruption in Sporting Life until 1917, when its doors were forever closed due to the outbreak of World War I.

He died on February 12, 1926.

Influence

By the end of the first quarter of the 20th century, Richter had acquired a reputation as one of baseball's most influential personalities. In fact, he had acquired so much renown that in 1907 the National League offered him the presidency of the league. Richter declined the offer, wanting instead to promote baseball "by lift(ing) the game up to the heights" of a national pastime (Reach Guide, 1926, p. 351).

Richter succeeded in lifting the game to these heights, seeing the sport through its darkest scandal in 1920 after the Black Sox Scandal. He continued his prestigious writing career, always seeking to improve the national sport, until the day before his death.

Richter had roles in the promotion of baseball and sportsmanship, as a player's advocate in salary wars, as a force in the amalgamation of the National and American Association into a twelve-team National League in 1892, in the formation of a new National Agreement (where, however, he opposed the reserve clause as adopted), in prestigious rules committees, and as a mouthpiece against gambling. He had prominent roles in areas such as promotion, record-keeping and shaping of public opinion. He was a financial backer of the 1884 Union Association and its Philadelphia team. He declared the new league "the emancipator of enslaved players and the enemy of the reserve clause" (Voigt, 1966, p. 130).

After the failure of the Players' League in 1890, Richter changed his allegiance, writing in the Sporting News that "Amidst all this noise and confusion the star ball player is the only one who can't lose, no matter which side wins" (Shaw, 2003).

He was the author of History and Records of Baseball: the American Nation's Chief Sport (Philadelphia: Sporting Life Publishing Co., 1914).

Richter died in his Philadelphia home on February 12, 1926 at the age of 71, the day after completing the 1926 edition of the Reach Official Guide. The cause of death was bronchial pneumonia. He was survived by his wife Helen and their two children, and was buried without fanfare in the Rockland section, Lot 248 at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, joining his son Chandler D. Richter, who had died in the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918. Al Reach (1840-1928) is buried in the same cemetery, Franconia section, Lot 54.

Obituary in the 1926 Spalding Guide

Mr. Richter founded Sporting Life and was one of the best informed men in the world in regard to the game of Base Ball. He advocated changes in rules from time to time, assisted in the amalgamation of the American Association and the National League in 1891, and at one time was offered the presidency of the National League. For many years Mr. Richter edited Reach's American League Guide and was an advocate always of the higher ethics of professional sport. He was for clean Base Ball through and through, and the best policies for the game as a national pastime had no stronger supporter in all the coterie of great Base Ball writers who flourished when Base Ball was beginning to get away from its minor surroundings to its present position in sport.

See also

Bibliography

- Richter, F. Richter's History and Records of Baseball: The American Nation's Chief Sport. Philadelphia: Sporting Life Publishing Co., 1914.

- Voigt, D. American Baseball: From Gentlemen's Sport to the Commissioner System. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966.

References

- This article is based on the Baseball Reference Bullpen article. The original can be viewed here. It is available under the GNU Free Documentation License.

External links

- "The Impact of Francis Richter upon the Development of Baseball" (page 1 of 5) by Amber Shaw, 2003

- Francis Richter at Library of Congress Authorities, with 5 catalog records