Freedom of Information Act (Illinois)

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 ILCS 140/1 et seq., is an Illinois statute that grants to all persons the right to copy and inspect governmental records in the state. The law applies to executive and legislative bodies of state government, units of local government, and other entities defined as "public bodies". All records related to governmental business are presumed to be open for inspection by the public, except for information specifically exempted from disclosure by law. The statute is modeled after the federal Freedom of Information Act and serves a similar purpose as freedom of information legislation in the other U.S. states.

| Freedom of Information Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| 83rd Illinois General Assembly | |

| Citation | 5 ILCS 140/1 et seq. Public Act 83-1013 |

| Passed | June 28, 1983 |

| Signed | December 27, 1983 |

| Signed by | Governor James R. Thompson (after amendatory veto agreed to by the General Assembly) |

| Effective | July 1, 1984 |

| Legislative history | |

| Bill | HB 234 |

| Introduced by |

|

| Amended by | |

| Public Act 96-542 (effective January 1, 2010) | |

| Related legislation | |

| |

| Status: Amended | |

Once a person submits a request to inspect public records, the public body is required to respond within deadlines specified by FOIA. Under certain circumstances, the public body may charge fees for providing the records. Public bodies are authorized to deny access to certain types of information enumerated by FOIA and other statutes. Persons denied access to information may appeal to the Public Access Counselor (PAC) or the circuit courts.

Illinois was the last state in the United States to enact freedom of information legislation. Before FOIA became effective in 1984, statutes granted limited access to records held by certain officials or governmental bodies, and courts recognized the public's right to access other records, subject to limitations established through common law. FOIA became the exclusive disclosure statute that filled the gaps left by other statutes, and it expanded the public's right to access information. An overhaul of FOIA became effective in 2010, turning the Illinois law into one of the most liberal and comprehensive public records statutes throughout the United States. The new law strengthened FOIA's enforcement provisions and authorized the PAC to resolve disputes.

Purpose

Illinois law has recognized the public's right to access and inspect public records and information about the workings of their government.[1] The courts have also recognized a common law duty to disclose public records, balanced against an individual's right to privacy and the interests of the government.[2] Access to records concerning the use of public funds is guaranteed by the Constitution of Illinois, which provides: "Reports and records of the obligation, receipt and use of public funds of the State, units of local government and school districts are public records available for inspection by the public according to law."[3] This constitutional provision has been implemented through the State Records Act and Local Records Act,[lower-alpha 1] which require agencies to permit inspection and copying of records related to public funds.[4] Certain statutes have also required specific officials to make their records open to public inspection.[5]

Since the public policy of Illinois has promoted access to public records, the enactment of FOIA did not drastically change the substance of Illinois law. FOIA is significant because it provides a comprehensive statutory statement of longstanding public policy, provides a codified balancing of competing interests recognized by common law, and establishes procedures to promote public inspection of records.[6] The purpose of FOIA is codified in section 1 of the act:[7]

Pursuant to the fundamental philosophy of the American constitutional form of government, it is declared to be the public policy of the State of Illinois that all persons are entitled to full and complete information regarding the affairs of government and the official acts and policies of those who represent them as public officials and public employees ... Such access is necessary to enable the people to fulfill their duties of discussing public issues fully and freely, making informed political judgments and monitoring government to ensure that it is being conducted in the public interest.

However, FOIA further states that it is not intended to cause an invasion of personal privacy, to allow commercial interests to impose a burden on public resources, or to disrupt the other responsibilities of public bodies aside from their duty to provide access to public records.[7]

The Illinois FOIA is modeled on the federal FOIA. The legislature intended that case law interpretations of the federal FOIA guide the Illinois courts in interpreting the state FOIA,[8] though Illinois courts have also noted that the state and federal FOIAs may still be interpreted differently.[9]

History

Prior to enactment

The first Illinois statutes concerning public access to records involved county officers. A law enacted in 1887 granted public access to records in the possession of a county recorder, and other statutes granted access to records of a county clerk or board of supervisors. The courts also recognized the legislature's authority to grant access to records in 1867, and the public's right to copy records in 1907. In the following years, the General Assembly began to enact disclosure provisions into various statutes, but such provisions were non-uniform and pertained only to specific agencies. Not all agencies were covered by disclosure requirements, and in those cases where a statute did not apply, the courts came to rely on common law to preserve the public's access to information. Common law granted taxpaying residents of a village or school district the right to inspect and copy records.[10] However, appellate case law also held that private financial records submitted to a city government by franchise applicants were not public records, as they were private business records that happened to be in the possession of city officials.[11] Under common law, whether a document was considered a public record was based on the purpose of the law that related to that type of document. A record may be considered a public record for one purpose, but not another.[12] Common law was used to balance the public's right to know against competing interests, such as the rights to privacy and due process of the subject of the information, along with the government's ability to conduct its business efficiently and without undue interference. Due to a lack of guidance from the General Assembly, the courts often weighed these factors differently, arriving at inconsistent decisions for each case.[13]

The General Assembly enacted the State Records Act in 1957, and the Local Records Act in 1961. However, neither statute provided general access to records. The State Records Act was primarily concerned with the financial records of the state government.[13] In 1979, the Supreme Court held in Lopez v. Fitzgerald[lower-alpha 2] that while the Local Records Act requires the preservation of public records, it does not impose an obligation on agencies to allow access to those records.[14] Also, the Constitution of Illinois ensures that the financial records of local governments are open to disclosure, but since the Constitution also protects an individual's personal privacy, courts addressing constitutional questions were again faced with the balancing tests similar to common law.[15]

Exemptions under the State Records Act and Local Records Act were vague, but the laws did provide exemptions against invasions of privacy. Furthermore, common law recognized an exemption for "preliminary documents", applying to records that were "part of an investigation or decision making process upon which final action had not been taken".[16]

Original version in 1983–1984

.jpg.webp)

Illinois was the last state in the United States to enact freedom of information legislation.[17] The initial version of FOIA, labeled House Bill 234, was introduced to the House of Representatives by Barbara Flynn Currie on February 9, 1983. After consideration by the Judiciary Committee, the bill passed the House on May 25, 1983, and proceeded to the Senate. There, the bill was sponsored by Terry L. Bruce and passed on June 27, 1983, after being considered by the Executive Committee. The House concurred in the Senate's amendments the following day.[18]

The law was detailed and comprehensive in its attempt to fill the gaps left by the State Records Act and Local Records Act. The new law defined the scope of FOIA's provisions, and specified the process through which a person can request records from a public body.[19] The new statute codified the common law exemption for "preliminary documents". Courts no longer had to resort to common law balancing tests as frequently as before, unless privacy issues or preliminary documents were involved. FOIA became the exclusive disclosure statute for agencies not already subject to other disclosure statutes, and raised the minimum standards for disclosure above those previously granted under the common law.[20]

Governor James R. Thompson issued an amendatory veto[lower-alpha 3] on September 23, 1983,[18] which weakened the bill by expanding exemptions and removing criminal penalties for non-compliance, among other things.[22] His usage of the amendatory veto had been controversial during his administration.[23] After the Illinois Constitution of 1970 granted this power for the first time, no other governor had issued amendatory vetos more extensively than Thompson did, and his actions often created policy disagreements with the General Assembly.[24] Currie considered Thompson's veto a "substantial rewrite" of House Bill 234, and an "invasive abuse of the amendatory veto".[25] Michael Madigan, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, wanted to use the bill as a test case to challenge the Governor's amendatory veto power. However, proponents of the bill did not want to risk losing the case, which would have caused the bill to die.[26] Legislators ultimately did not consider whether the Thompson had exceeded his veto powers.[23] The General Assembly agreed to accept the proposed amendments on November 2, 1983. With Thompson's certification on December 27, 1983, the law was enacted as Public Act 83-1013, and it became effective on July 1, 1984.[18]

Overhaul in 2009–2010

| Public Act 96-542 | |

|---|---|

| 96th Illinois General Assembly | |

| Passed | May 28, 2009 |

| Signed | August 17, 2009 |

| Signed by | Governor Pat Quinn |

| Effective | January 1, 2010 |

| Legislative history | |

| Bill | SB 189, House Floor Amendment No. 2 |

| Introduced by |

|

| Amends | |

| |

Even with the requirements of FOIA codified into law, its original version was criticized for weak enforcement provisions. Public bodies were unlikely to face repercussions when denying or ignoring FOIA requests. Requesters could seek assistance from the Attorney General's Public Access Counselor (PAC), who could mediate disputes and write letters to encourage public bodies to comply with FOIA. However, the PAC had no formal enforcement powers, and its capacities were merely advisory and non-binding. This left the practical burden on requesters to pursue lengthy, time-consuming litigation. Requesters were not likely to appeal to the courts, creating a natural deterrent that public bodies leveraged to avoid full compliance.[27]

An audit conducted by the Better Government Association in 2006 revealed that 62% of public bodies did not comply with FOIA, and 39% did not respond to FOIA requests at all.[28] The Better Government Association also conducted a survey in 2008 with the National Freedom of Information Coalition, ranking Illinois among the 38 out of 50 states receiving a grade of "F" for their versions of FOIA.[29][30] In addition, the public was contending with a history of corruption in Illinois, considered at the time to be one of the most corrupt states in the United States.[31] Governor Rod Blagojevich had several scandals during his administration, including corruption charges in December 2008 that led to his impeachment and removal from office.[32][33]

Starting in January 2009, Attorney General Lisa Madigan worked on draft legislation to amend FOIA with the Illinois Press Association, the Illinois Campaign for Political Reform, the Better Government Association, and Citizen Advocacy Center.[33] The legislation was introduced in the House of Representatives by Michael Madigan on May 27, 2009, as a floor amendment to Senate Bill 189.[lower-alpha 4] The bill passed the House the same day, then proceeded to the Senate, where it was sponsored by Kwame Raoul. The Senate concurred in the House's amendment on May 28, 2009. Governor Pat Quinn signed the bill, enacted as Public Act 96-542 on August 17, 2009.[34]

The legislation became effective on January 1, 2010, issuing the most sweeping changes to FOIA since the original enactment in 1984.[17] The amendments roughly doubled the size of the Act based on its word count.[35] The Illinois FOIA became considered one of the most liberal and comprehensive public records statutes throughout the United States.[36][37]

Changes to FOIA

The changes narrowed the definition of "private information" to certain unique identifiers. The privacy exemption, which was previously used to deny access to information about the names, titles, and compensation of public employees, was also updated to require a balancing test between the "subject's right to privacy" and "any legitimate public interest in obtaining the information". The new rules also explicitly stated that settlement agreements, often withheld previously under the privacy exemption, are now subject to disclosure.[38]

Requesters were also allowed to submit complaints to the PAC, which became a more viable alternative to litigation because it leveled the "playing field" between two government agencies, rather than pitting private citizens against public bodies with more resources. The General Assembly formally recognized and granted additional enforcement powers to the PAC, by amending the Attorney General Act[lower-alpha 5] at the same time as FOIA. With these changes, the PAC could issue subpoenas and file lawsuits in the circuit courts to force compliance with a binding opinion or prevent a FOIA violation.[39]

Reactions

The Illinois Municipal League, representing local governments, opposed the changes as "overly burdensome" and "unworkable". It further contended that the updated version of FOIA resulted in a "confusing and complex system for FOIA responses", and presented a "legal thicket" that is overwhelming to officials who process FOIA requests.[1] The Illinois States Attorneys Association also objected, as the Attorney General and the PAC acquired an expanded role under the new law. The Association suggested that the role of the state's attorney should be expanded instead.[40]

Watchdogs and other residents who frequently file FOIA requests had mixed reviews of the amendments. Peter Gonigam, a resident and journalist from Carpentersville, claimed that public bodies could still find ways to frustrate FOIA requesters under the new law, but liked the new appeals process through the PAC.[41] David Kidwell, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, expressed concerns about "sweeping" exemptions that still remained, including the privacy or preliminary drafts exemptions.[33]

Subsequent developments

Two weeks after Public Act 96-542 became effective, the General Assembly quickly passed a law that exempted the performance evaluations of school superintendents, principals, and teachers from disclosure.[42] By the end of 2010, the General Assembly passed another law that exempted all public employees' performance evaluations from disclosure.[17] In 2011, more than three dozen bills were introduced in the General Assembly to amend FOIA, most with the goal of reducing disclosure requirements as a backlash to Public Act 96-542. The proposals included bills that would have reduced the rights of "vexatious" requesters, added more exemptions to FOIA, or allowed public bodies to charge higher fees.[43]

In 2015, the Center for Public Integrity reviewed every state's public records laws, giving Illinois a grade of "F". The group contended that the state's enforcement of FOIA is weak, and that public bodies often claim the exemption for requests that are "unduly burdensome". Still, Illinois ranked as the 15th most transparent state under the criteria used by the Center for Public Integrity.[44] Additionally, ProPublica and the Chicago Sun-Times published a report on the PAC in 2018, labeling it "an overwhelmed and inconsistent enforcement system". The PAC has rarely used its full authority to enforce FOIA, and violators have faced few consequences for ignoring the PAC's opinions.[45]

Scope

Public bodies

FOIA applies to all "public bodies" in Illinois. Public bodies include:[46]

- legislative, executive, administrative, and advisory bodies of the government of Illinois, including boards, bureaus, and commissions

- state universities and colleges

- local governments in Illinois including counties, townships, municipalities, school districts, and all other municipal corporations

- subsidiary bodies, such as committees and subcommittees, of the aforementioned entities

- School Finance Authorities created under the Downstate School Finance Authority Law[lower-alpha 6]

However, public bodies do not include child death review teams, the Illinois Child Death Review Teams Executive Council, regional youth advisory boards, or the Statewide Youth Advisory Board.[lower-alpha 7][46] Additionally, FOIA does not apply to quasi-governmental bodies, such as economic development or strategic planning groups.[47]

While the executive and legislative branches are subject to FOIA, the judicial branch is not. Therefore, FOIA does not apply to courts and entities that report to the chief judge, such as a probation department. The Illinois Courts Commission, an adjudicative body of the judiciary, is also exempt.[48] However, court proceedings and related documents are generally open to the public.[49]

The textual definition of "public bodies" in FOIA is nearly identical to "public bodies" under the Open Meetings Act,[lower-alpha 8] a related Illinois statute that requires meetings to be open to the public. However, the scope of "public bodies" is broader under FOIA, and includes individual officers and agencies who do not hold meetings. However, officials who are merely members of public bodies (such as members of a city council) are not separately considered "public bodies" in their individual capacities.[50]

Public records

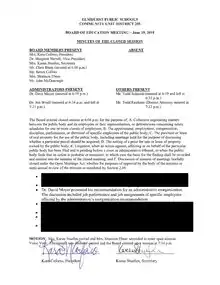

.jpg.webp)

FOIA requires the disclosure of "public records", which includes records "pertaining to the transaction of public business, regardless of physical form or characteristics, having been prepared by or for, or having been or being used by, received by, in the possession of, or under the control of any public body".[46] Records related to public funds, payrolls, arrest reports, criminal records, and settlement agreements are also considered "public records".[51] Records of a public body's contractors are subject to disclosure, provided that the records directly relate to a governmental function. Public bodies cannot contract out their governmental functions to evade disclosure under FOIA.[52]

FOIA does not require public bodies to create new records that do not already exist, unless a different law requires the records to be maintained. Public records may be stored in a wide range of formats, including paper, electronic, photographs, and audio or video recordings.[47] When the records are available in an electronic format, public bodies must provide the records in the format specified by the requester. In some cases, the requested format might not be feasible to the public body, in which case the public body may opt to provide the records in a different electronic format, or on paper.[53]

When it enacted the original version of FOIA, the General Assembly replaced the common law test with a more explicit listing of the types of documents that are to be considered public records.[lower-alpha 9] A court could easily check this listing to determine whether a record clearly fell within one of the examples provided in the statute. If so, then the General Assembly intended its disclosure. On the other hand, if the record fit neither the listed examples of public records nor the exemptions from disclosure, then the court had to look to other sources, such as specific statutes governing the agency in question, prior to making its determination. Courts could also refer to case law under the federal FOIA, which has a very broad interpretation of what constitutes a public record.[55] The enumerated list of examples was removed by Public Act 96-542.[56]

Records on private electronic devices

.jpg.webp)

Emails and other communications stored on private electronic devices may be subject to disclosure.[57] City of Champaign v. Madigan was the first decision by an Illinois court addressing whether the private emails of government officials are subject to FOIA.[58] In that case, the Appellate Court found that members of a city council do not constitute a "public body" when acting individually, but they do act collectively as a "public body" once they have convened a meeting to conduct public business. By this interpretation, if a constituent sends a message to a city council member at home on their personal device, that message would not be subject to FOIA even if it pertains to public business. However, messages sent and received by elected officials during a city council meeting are public records, regardless of whether they communicated via personal devices not owned by the city.[59]

Regarding employees (rather than elected members) of the public body, the applicability of City of Champaign was unclear, as a legal expert noted that "executive branch employees" act on the public body's behalf.[60] In May 2016, the Circuit Court of Cook County clarified the matter when it ruled that personal emails of Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel may be subject to disclosure, even when stored on private devices.[61] Later that year, the Attorney General ruled in Public Access Opinion 16-006 that officers of the Chicago Police Department were required to disclose their work-related emails stored on personal accounts.[58] In 2020, the Appellate Court ordered the release of correspondence held on private devices of several Chicago officials, including the mayor, his staff, and the public health commissioner.[62]

Exemptions

In 1988, there were 29 exemptions from disclosure listed in the statute.[63] By 2011, FOIA contained roughly 45 exemptions from disclosure, codified in sections 7 and 7.5 of the act.[lower-alpha 10] Section 7 contains exemptions that cover private information, personal information, records related to administrative enforcement proceedings, and preliminary drafts containing recommendations or opinions. (Enumerated below in more detail.) Section 7.5 contains "statutory" exemptions, referring to independent statutes that exempt specific types of information from disclosure under FOIA. For example, performance evaluations for all public employees are exempt under section 7.5.[17] Noteworthy exemptions include, but are not limited to:[64][65]

- Information specifically exempted from disclosure by state or federal law.

- Private information, which includes unique identifiers and personal data such as Social Security numbers, driver's license numbers, employee identification numbers, biometrics, passwords, medical records, personal telephone numbers, personal email addresses. Private information also includes home addresses and personal license plate numbers, except when disclosure is required by law or when the information is compiled without possible attribution to a person.

- Personal information that, if disclosed, would constitute a "clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy", which means "disclosure of information that is highly personal or objectionable to a reasonable person and in which the subject’s right to privacy outweighs any legitimate public interest in obtaining the information". Information that relates to the public duties of a public employee is not considered an invasion of personal privacy.

- Law enforcement records that, if disclosed, would interfere with a pending or "contemplated" proceeding, disclose the identity of a confidential source, or endanger the life or physical safety of any person.

- Preliminary drafts, notes, or recommendations in which opinions are expressed or policies are formed. However, records that are publicly cited and identified by the head of the public body[lower-alpha 11] are not exempt from disclosure.

- Business trade secrets or commercial information that is confidential, and disclosure would cause competitive harm.

- Procurement proposals and bids until a final selection is made.

- Formulae, designs, drawings, and research data if disclosure would produce private gain or public loss.

- Educational records including test questions and scoring keys, and course materials or research materials used by faculty.

- Minutes of meetings closed to the public under the Open Meetings Act.

- Attorney communications protected by attorney–client privilege.

FOIA does not require public bodies to withhold information, and asserting an exemption is at the discretion of the public body.[66] All public records are presumed to be open to the public. If a public body wishes to claim that specific information is exempt from disclosure, it "has the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that it is exempt."[67] Thus, the law is broadly interpreted in favor of openness and disclosure, and exemptions are strictly construed.[68] In Lieber v. Board of Trustees of Southern Illinois University,[lower-alpha 12] considered to be the seminal case regarding FOIA, the Supreme Court held that as long as a public body can prove that the information falls within the scope of an exemption specified by FOIA, then the information is per se exempt from disclosure.[69]

Requesting records

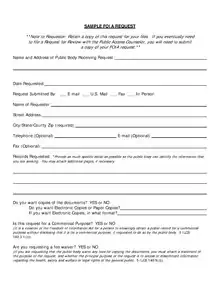

All public bodies are required to appoint at least one FOIA officer, who is responsible for receiving and responding to FOIA requests. FOIA officers also complete annual training offered by the PAC. Public bodies are required to publicly display the names and contact information of its FOIA officers, along with instructions on how to submit a FOIA request.[70]

Any person may submit a FOIA request, including people who live outside Illinois. Most FOIA requests come from non-journalists.[71] Requesters may make their FOIA request in writing, such as by postal mail, email, fax, or in person. Public bodies may also accept oral requests, but are not required to do so. Public bodies cannot require requesters to use a specific form.[72]

Deadlines and responses

Under the original version of FOIA, public bodies were given 7 working days to comply with a request, and were allowed to extend their deadlines by an additional 7 days under certain circumstances.[19] These timelines were shortened by Public Act 96-542, which required public bodies to respond to non-commercial FOIA requests within 5 business days.[73] Public bodies may extend their deadlines by 5 business days under certain circumstances, and must explain to the requester the reason for the extension. Additionally, requesters and public bodies may reach their own agreements to grant more time for public bodies to comply with the request.[74]

Requesters cannot be compelled to explain the purpose of their requests, except to determine whether the records will be used for a "commercial purpose". If the request is for commercial purposes, the deadline for the public body to respond increases from 5 to 21 business days. Commercial requests do not include those made by news, non-profit, scientific, or academic organizations.[75] Public bodies cannot deny requests solely because they have a commercial purpose. Although the original legislation effective in 1984 stated that FOIA was not intended "for the purpose of furthering a commercial enterprise," this statement was in the preamble, not in the body of the act. Therefore, the Supreme Court held in Lieber that it had no legal force.[76] Public bodies in local government have considered FOIA requests from large commercial entities to be among the most burdensome unfunded mandates.[77]

If a request is denied, the public body must issue its denial in writing, and provide the legal reasons for withholding the information.[78] Public bodies may deny requests as "unduly burdensome" if fulfilling the request would interfere with the public body's operations in a way that outweighs the public's interest in disclosure, and the scope of the request cannot be narrowed.[79]

During the initial response in April 2020 to the COVID-19 pandemic in Illinois, nearly 200 mayors and the Illinois Municipal League urged Attorney General Kwame Raoul to extend the deadline to respond to FOIA requests, as public bodies were operating with fewer employees and struggled to maintain core services. However, Raoul's office contended that it did not have the authority to suspend FOIA deadlines during the pandemic; only the governor or the General Assembly could do so.[80] In May 2020, the General Assembly considered a bill that would have postponed all FOIA deadlines by 30 days. The proposal was controversial, with opponents emphasizing the importance of transparency as governments confronted COVID-19. The office of Governor J. B. Pritzker opposed the measure, and it failed by one vote in the House of Representatives.[81]

Fees

Public bodies may charge fees for providing copies of records, according to a standard fee schedule that must be publicly available.[76] The bill initially proposed in 1983 stated that public bodies could charge a maximum of 50 cents per page, but this provision was deleted by the Senate in favor of allowing public bodies to charge the actual costs of copying the records. Additionally, the initial version of the bill allowed for a waiver of fees if the requester was "indigent". Governor Thompson struck this provision by amendatory veto,[lower-alpha 3] noting that there was no objective criteria to determine whether a person is indigent.[82] Starting in 2010, Public Act 96-542 set limits on the amount of fees that may be charged to a requester.[73] For black-and-white copies on letter or legal size paper, the first 50 pages are free, and additional pages may cost up to 15 cents per page. For other types of records, public bodies may continue to charge fees that cover the actual costs of copying or providing the required storage media.[53] Public bodies may waive fees if disclosure is in the "public interest", meaning that the information concerns the welfare or rights of the general public, and disclosure does not provide a personal or commercial benefit.[76]

Public bodies may not charge for staff's time spent searching for and reviewing the records.[76] An Illinois task force on local government found FOIA compliance to be an unfunded mandate, and agencies have reported high personnel costs to hire full-time FOIA officers.[83]

Enforcement

Head of the public body

Under the original version of FOIA, if a public body denies a FOIA request, the requester must first appeal to the head of the public body.[lower-alpha 11] If the head of the public body affirmed the denial, or failed to respond within 7 days, then the requester could file litigation in court.[84] Public bodies were advised to appoint other employees to initially handle FOIA requests, so that the head could focus on appeals and obtain legal advice as needed.[85] However, this process was viewed as "perfunctory" and repealed by Public Act 96-542,[40] which allowed requesters to file litigation immediately after receiving the initial denial.[33]

Litigation

The requester may appeal by filing litigation in the circuit court, and there is no deadline for the requester to file suit.[86] When litigation is filed, the court considers the matter de novo and conducts an in camera review of the records to determine whether the information is exempt from disclosure.[87] FOIA cases take precedence on the court's docket.[84] If the court finds that FOIA has been violated, it may provide injunctive or declaratory relief, ordering the disclosure of records. The court's orders are enforceable through its contempt powers.[86]

FOIA originally allowed the court to award attorney fees to a requester who "substantially prevailed" in litigation, but only if the records were "of clearly significant interest to the general public" and if the public body lacked "any rational legal basis" for denying the request.[86] However, the court could not impose civil penalties on the public body.[88]

Public Act 96-542 introduced civil penalties between $2,500 and $5,000 per violation, if the court finds that the public body "willfully and intentionally" violated FOIA.[89] The new law also imposed mandatory awards of attorney fees to requesters who prevail in litigation.[90]

Public Access Counselor

The requester may also appeal to the PAC within 60 days of the FOIA denial. Unlike litigation, the PAC review process is available at no cost to the requester. However, FOIA requests to the General Assembly or its subsidiary bodies may not be appealed to the PAC. The PAC will review whether the FOIA request was properly denied, and may issue a subpoena to obtain more information. Requesters may not appeal through the PAC and the courts at the same time. If the PAC is already reviewing the matter when a lawsuit is filed, then the requester must notify the PAC, who will stop its review and take no further action.[91]

The PAC may issue a binding opinion within 60 days of receiving the complaint, and this timeline may be extended by an additional 21 days. If the PAC issues a binding opinion, the result is binding on the requester and the public body, but either side may continue to appeal in court under administrative review.[92] Binding opinions also establish precedent for other public bodies issuing FOIA denials under similar circumstances.[93] Binding opinions are rare, as they are issued for only less than half of one percent of complaints submitted to the PAC. The PAC generally issues binding opinions on "issues of broad public interest", and is careful to research each case to ensure that its opinions are upheld by the courts. Journalists and news organizations are more likely than private citizen requesters to receive a binding opinion.[45]

When the PAC declines to issue a binding opinion, it is no longer bound by any statutory deadlines to resolve the matter. It may issue a non-binding or advisory opinion, resolve the dispute through mediation, or decide to take no further action on the matter. Requesters often wait months or years before their appeals are reviewed by the PAC. Of the more than 28,000 appeals filed with the PAC from January 2010 through August 2018, over 3,800 appeals took more than one year to resolve, and about 500 took more than four years to resolve.[45]

Public Act 96-542 required public bodies to seek pre-approval from the PAC prior to denying records based on the personal privacy or preliminary drafts exemptions, even without the requesters initiating their own complaints.[39] Once this requirement became effective in 2010, pre-approval of FOIA denials eventually comprised a large portion of the PAC's workload.[94] Of the complaints received by the PAC in 2010, 63 percent were requests for pre-approval of a FOIA denial.[95] This requirement was repealed by the end of 2011 to ease the workload of the PAC and public bodies.[94]

Notes

- State Records Act (5 ILCS 160/1 et seq.), Local Records Act (50 ILCS 205/1 et seq.)

- Lopez v. Fitzgerald, 76 Ill. 2d 107, 390 N.E.2d 835 (1979).

- In an amendatory veto, the Governor makes specific changes and recommendations to the bill. The bill returns to the General Assembly, along with a message indicating that the Governor would approve the bill if the changes are made. The General Assembly can agree to the changes with a simple majority, override the Governor's veto with a three-fifths majority, or let the bill expire by doing nothing.[21]

- Senate Bill 189 was originally introduced to address an unrelated matter regarding gubernatorial appointments. House Floor Amendment No. 2 replaced the entire bill with new legislation that later became the final version.[34]

- Attorney General Act (15 ILCS 205/0.01 et seq.)

- Downstate School Finance Authority Law (105 ILCS 5/1E-1 et seq.)

- Child death review teams and the Illinois Child Death Review Teams Executive Council are created by the Child Death Review Team Act (20 ILCS 515/1 et seq.). Regional youth advisory boards and the Statewide Youth Advisory Board are created by the Department of Children and Family Services Statewide Youth Advisory Board Act (20 ILCS 527/1 et seq.).

- Open Meetings Act (5 ILCS 120/1 et seq.)

- Enumerated examples of public records included, but were explicitly not limited to:[54]

- Administrative manuals, procedural rules, and staff instructions, except for records related to information security

- Adjudicative opinions and orders, except for student or school employee disciplinary cases

- Substantive rules

- Policy statements and interpretations

- Final planning policies, recommendations, and decisions

- Factual reports, inspection reports, and studies

- Information dealing with receipt or expenditure of public funds

- Employment and compensation information for personnel and officers

- Opinions concerning the rights of the state, the public, a governmental agency, or a private person

- Reports of proceedings of public bodies

- Applications for contracts, permits, grants, or agreements, except for trade secrets and commercial information that is confidential

- Reports prepared by consultants and contractors for the public body

- All other information required by law to be made publicly available

- Grants or contracts with another public body or a private organization

- Section 7: 5 ILCS 140/7, Section 7.5: 5 ILCS 140/7.5

- FOIA defines "head of the public body" as "the president, mayor, chairman, presiding officer, director, superintendent, manager, supervisor or individual otherwise holding primary executive and administrative authority for the public body, or such person's duly authorized designee".[46]

- Lieber v. Board of Trustees of Southern Illinois University, 176 Ill. 2d 401, 680 N.E.2d 374 (1997).

Citations

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, p. 6.

- Ryan 1999, p. 5.

- Article VIII, Section 1(c) of the Constitution of Illinois (1970)

- Ryan 1999, p. 6.

- Madigan 2004, p. 6.

- Ryan 1999, p. 7.

- Freedom of Information Act (5 ILCS 140/1). Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- Craven 2020, Foreword.

- Madigan 2004, p. 7.

- McGill 1985, pp. 81–82 & nn. 25–27, 32.

- Kosnoff 1980, p. 1150.

- McGill 1985, p. 92.

- McGill 1985, p. 83.

- Kosnoff 1980, p. 1156.

- McGill 1985, pp. 84–85.

- McGill 1985, pp. 93–94.

- Roth, Stephan; Romas-Dunn, Jeannie (June 2011). "Freedom of Information Act — Recent & proposed changes" (PDF). The Public Servant. Illinois State Bar Association. 12 (4): 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "HB-0234". Legislative Synopsis and Digest. 83rd Illinois General Assembly, 1983 Session. Springfield, Illinois: Legislative Reference Bureau, Illinois General Assembly.

- McGill 1985, p. 85.

- McGill 1985, p. 90, 94.

- Paprocki, Matt (August 2, 2017). "Illinois' Gubernatorial Veto Procedures". Illinois Policy. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- Helle 2010, p. 1089.

- Ourth 1987, p. 708.

- Ourth 1987, pp. 692–693.

- Ourth 1987, n. 115.

- Bandes, Susan A. (Summer 2007). "Law Stories: Tales from Legal Practice, Experience, and Education: When Freedom of Information Came to Illinois" (PDF). UMKC Law Review. 75 (4): 1145–1147. ISSN 0047-7575. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2020 – via Susan Bandes.

- Klaper 2010, pp. 68–69.

- Stewart, Jay; Sprehe, Dan (October 26, 2006). "Curiosity Killed the Cat: A report on compliance with the Illinois' Freedom of Information Act". Better Government Association. Archived from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Helle 2010, p. 1103.

- BGA; Davis, Charles (November 1, 2008). "Report: Grading the United States on FOIA responsiveness". Better Government Association. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Harmon 2013, pp. 602–603.

- Stewart 2010, p. 266.

- Ericson, Brooke (Fall 2009). "Illinois revises transparency laws on heels of scandal". News Media & the Law. 33 (4): 18. ISSN 0149-0737 – via Communication & Mass Media Complete.

- "Bill Status of SB0189 – 96th General Assembly". Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Helle 2010, p. 1094.

- Harmon 2013, p. 602.

- Klaper 2010, p. 65.

- Klaper 2010, p. 70.

- Klaper 2010, p. 75.

- Helle 2010, p. 1091.

- Craver, Kevin P. (August 5, 2010). "Frequent filers weigh in on FOIA". Northwest Herald. Shaw Media. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Helle 2010, p. 1104.

- Kidwell, David (April 3, 2011). "Recently overhauled laws on open records face backlash". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Thomas, David (April 24, 2019). "Ten years after the state's FOIA overhaul". Chicago Daily Law Bulletin. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Dumke, Mick (October 11, 2018). "Citizens Count on the Illinois Freedom of Information Act but Keep Getting Shut Out". ProPublica. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- Freedom of Information Act (5 ILCS 140/2). Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, p. 8.

- Madigan 2004, pp. 8–9.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, p. 2.

- Madigan 2004, p. 8.

- "Citizen Advocacy Center Guide to Illinois' Freedom of Information Act" (PDF). Citizen Advocacy Center. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- Craven 2020, Open Records § I.B.4, I.C.1.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, p. 5.

- Public Act 83-1013 (eff. July 1, 1984), enacting section 2(c) of FOIA (5 ILCS 140/2(c))

- McGill 1985, pp. 92–93.

- Public Act 96-542 § 10 (eff. January 1, 2010), amending section 2(c) of FOIA (5 ILCS 140/2(c))

- Craven 2020, Open Records § I.C.6.

- Brown, Jeffery M. (Summer 2017). "Collision Course of Legal Obligations: FOIA, Collective Bargaining and Privacy Considerations". Illinois Public Employee Relations Report. 34 (3): 9–10, 14. ISSN 1559-9892. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020.

- Lasker, Adam W. (December 2013). "Aldermen's texts, tweets during council meetings are 'public records'". Illinois Bar Journal. Illinois State Bar Association. 101 (12): 606. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- O'Connor, John (October 11, 2015). "FOIA issue of emails on private devices goes back to court". The State Journal-Register. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- Kidd, Karen (August 22, 2016). "Atty Gen declares city workers' emails, texts to be public info, but raises more legal questions". Cook County Record. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- Holland, Scott (August 17, 2020). "Appeals panel agrees: Public employees' private messages may fall under FOIA, if they're talking public business". Cook County Record. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- McManus 1988, p. 159.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, pp. 9–10.

- McGill 1985, pp. 87–88.

- Craven 2020, Open Records § II.A.1.

- Freedom of Information Act (5 ILCS 140/1.2). Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Klaper 2010, p. 67.

- Lenzini, Phillip B. (April 2006). "Job evaluations and personnel files under the Freedom of Information Act". The Public Servant. Illinois State Bar Association. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, pp. 1, 3.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, p. 10.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, p. 3.

- Klaper 2010, p. 72.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, pp. 4–5.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, pp. 5, 10–11.

- Uhler, Scott; Petsche, Janet; Allison, Rinda (Winter 1999). "Questions and Answers on Library Law: The Freedom of Information Act, Part 2". Illinois Libraries. Illinois State Library. 81 (1): 20–22. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020 – via Northern Illinois University Libraries.

- Koningisor 2020, p. 1502 & n. 225.

- Illinois Attorney General 2013, p. 6.

- Miller, Robert L. (March 2017). "Demystifying "unduly burdensome" under FOIA". The Public Servant. Illinois State Bar Association. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Rowland, Brett (April 13, 2020). "Mayors ask Illinois Attorney General for more time to respond to requests for public records". The Center Square. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Nowicki, Jerry (May 24, 2020). "Restore Illinois commission bill passes after removal of remote session, FOIA delay language". Herald & Review. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- McGill 1985, p. 88 & n. 87.

- Koningisor 2020, p. 1495 & nn. 180, 183.

- McGill 1985, p. 86.

- Uhler, Scott; Petsche, Janet; Allison, Rinda (Spring 1998). "Questions and Answers on Library Law: The Freedom of Information Act". Illinois Libraries. Illinois State Library. 80 (4): 220–221. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015 – via Northern Illinois University Libraries.

- Uhler, Scott; Petsche, Janet; Allison, Rinda (Spring 1999). "Questions and Answers on Library Law: The Freedom of Information Act, Part 3". Illinois Libraries. Illinois State Library. 81 (2): 79–82. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015 – via Northern Illinois University Libraries.

- Craven 2020, Open Records § IV.E.4.a.

- McGill 1985, p. 95.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, p. 23.

- Stewart 2010, p. 266, 309.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, pp. 21–22.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute 2011, p. 21.

- Kidwell, David; Germuska, Joe; Groskopf, Christopher; Boyer, Brian (April 1, 2011). "The process: What takes so long". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Franczek P.C. (September 2, 2011). "Attorney General Pre-Authorization No Longer Required Under Illinois FOIA Law for Personal Information and Predecisional Materials". JD Supra. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Attorney General Madigan: New Sunshine Laws Created More Government Transparency" (Press release). Chicago: Illinois Attorney General. January 6, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Illinois Compiled Statutes.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Illinois Compiled Statutes.

![]() This article incorporates text by Burris 1994 available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Burris 1994 available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

![]() This article incorporates text by Ryan 1999 available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Ryan 1999 available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- Burris, Roland W. (January 12, 1994). A Guide to the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (Report). Springfield, Illinois: Attorney General, State of Illinois. Retrieved January 3, 2021 – via HathiTrust.

- Craven, Donald M. (September 15, 2020). "Open Government Guide – Illinois". Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Harmon, Alyssa (2013). "Illinois's Freedom of Information Act: More Access or More Hurdles?" (PDF). Northern Illinois University Law Review. 33: 601–629. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Helle, Steven (2010). "Survey of Illinois Law: New Freedom of Information Act – Peeking Behind the Paper Curtain" (PDF). Southern Illinois University Law Journal. 34: 1089–1105. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- "Illinois Freedom of Information Act: Frequently Asked Questions by the Public" (PDF). Illinois Attorney General. September 9, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- Klaper, Sarah (Fall 2010). "The Sun Peeking Around the Corner: Illinois' New Freedom of Information Act as a National Model" (PDF). Connecticut Public Interest Law Journal. 10 (1): 63–100. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 9, 2020.

- Koningisor, Christina (2020). "Transparency Deserts". Northwestern University Law Review. 114 (6): 1461–1547. ISSN 0029-3571. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- Kosnoff, Kathy Suzanne (1980). "Denial of Public Access to Building Inspection Reports in Illinois: When Is a Public Record not Public". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 56 (4): 1147–1173. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- Madigan, Lisa (September 2004). A Guide to the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (PDF) (Report). Attorney General, State of Illinois. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020 – via Community Consolidated School District 46.

- McGill, Norman L. (1985). "Freedom of Information Act – Illinois Adopts a New Public Records Statute". Southern Illinois University Law Journal. 10 (1): 79–96. ISSN 0145-3432 – via HeinOnline.

- McManus, Ed (November 1988). "Meetings and Records in Illinois: How Open Are They?". Illinois Bar Journal. 77 (3): 156–163. ISSN 0019-1876 – via HeinOnline.

- Ourth, Joe R. (1987). "The Illinois Amendatory Veto: Defining and Enforcing the Limits". University of Illinois Law Review. 1987 (4): 691–730 – via HeinOnline.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute (2011). A Citizen’s Guide to Using the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (PDF) (Report). Southern Illinois University Board of Trustees. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020 – via Fox River & Countryside Fire/Rescue District.

- Ryan, Jim (September 1999). A Guide to the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (Report). Springfield, Illinois: Attorney General, State of Illinois. Retrieved January 3, 2021 – via HathiTrust.

- Stewart, Daxton R. "Chip" (2010). "Let the Sunshine in, Or Else: An Examination of the Teeth of State and Federal Open Meetings and Open Records Laws". Communication Law and Policy. 15 (3): 265–310. ISSN 1081-1680 – via HeinOnline.

External links

- Full text of the Freedom of Information Act (5 ILCS 140/1 et seq.)

- "Ensuring Open and Honest Government" – Website of the Public Access Counselor, which includes educational materials, training to FOIA officers, and binding opinions on FOIA disputes