Freedom of panorama

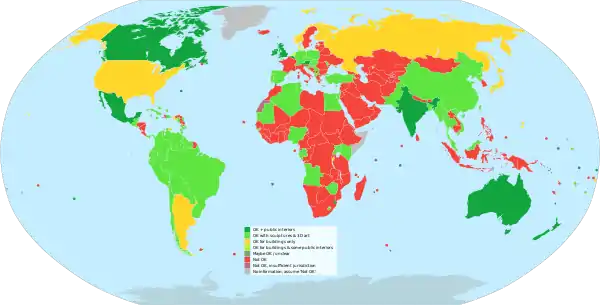

Freedom of panorama (FOP) is a provision in the copyright laws of various jurisdictions that permits taking photographs and video footage and creating other images (such as paintings) of buildings and sometimes sculptures and other art works which are permanently located in a public place, without infringing on any copyright that may otherwise subsist in such works, and the publishing of such images.[1][2] Panorama freedom statutes or case law limit the right of the copyright owner to take action for breach of copyright against the creators and distributors of such images. It is an exception to the normal rule that the copyright owner has the exclusive right to authorize the creation and distribution of derivative works. The phrase is derived from the German term Panoramafreiheit ("panorama freedom").

Laws around the world

Many countries have similar provisions restricting the scope of copyright law in order to explicitly permit photographs involving scenes of public places or scenes photographed from public places. Other countries, though, differ widely in their interpretation of the principle.[1]

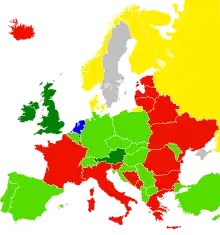

European Union

In the European Union, Directive 2001/29/EC provides for the possibility of member states having a freedom of panorama clause in their copyright laws, but does not require such a rule.[3][4][5]

Denmark

Article 24(2) of the Danish copyright law allows the pictorial reproductions of artistic works situated in public places, if the purpose is noncommercial. Article 24(3) states that buildings can be freely reproduced in pictorial form.[6]

.JPG.webp)

There is still no full freedom of panorama for non-architectural works in Denmark. The Little Mermaid, a sculpture of Edvard Eriksen (who died in 1959), is under copyright until 2034, and the Eriksen family is known to be litigious.[7] Several Danish newspapers have been fined for using images of the sculpture without permission from the Eriksen family. The purpose of the Danish media is considered commercial. Søren Lorentzen, photo editor of Berlingske which was one of the newspapers slapped with fines, once lamented, "We used a photo without asking for permission. That was apparently a clear violation of copyright laws, even though I honestly have a hard time understanding why one can’t use photos of a national treasure like the Little Mermaid without violating copyright laws." Alice Eriksen, granddaughter of the sculptor, defended the restrictions and said that such restrictions are in compliance of the laws of the country. She added, "It’s the same as receiving royalties when a song is played."[8][9]

France

Since October 7, 2016, article L122-5 of the French Code of Intellectual Property provides for a limited freedom of panorama for works of architecture and sculpture. The code authorizes "reproductions and representations of works of architecture and sculpture, placed permanently in public places (voie publique), and created by natural persons, with the exception of any usage of a commercial character".[10]

.jpg.webp)

CEVM (Compagnie Eiffage du Viaduc de Millau), the exclusive beneficiary of all property rights of Millau Viaduct on behalf of its architect Norman Foster, in their website explicitly requires that professional and/or commercial uses of images of the bridge are subject to "prior express permission of the CEVM". Additionally, CEVM has the sole right to distribute images of the viaduct in souvenir items such as postcards. However, private and/or noncommercial uses of images are tolerated by CEVM. Also exempted from obligatory permission and remuneration payment are "landscape images where the Viaduct appears in the background and is thus not the main focus of the image."[11]

Germany

Panoramafreiheit is defined in article 59 of the German Urheberrechtsgesetz.[12]

An example of litigation due to the EU legislation is the Hundertwasserentscheidung (Hundertwasser decision), a case won by Friedensreich Hundertwasser in Germany against a German company for use of a photo of an Austrian building.[13]

Italy

In Italy[14] freedom of panorama does not exist. Despite many official protests[15] and a national initiative[16] led by the lawyer Guido Scorza and the journalist Luca Spinelli (who highlighted the issue),[14] the publishing of photographic reproductions of public places is still prohibited, in accordance with the old Italian copyright laws[17][18] made more restrictive by a law called Codice Urbani which states, among other provisions, that to publish pictures of "cultural goods" (meaning in theory every cultural and artistic object and place) for commercial purposes it is mandatory to obtain an authorization from the local branch of the Ministry of Arts and Cultural Heritage, the Soprintendenza.

Romania

In Romania, the heirs of Anca Petrescu, the architect of the colossal Palace of the Parliament, sued the Romanian Parliament for selling photos and other souvenirs with the image of the iconic building. The copyright infringement trial is ongoing.[19]

Sweden

On April 4, 2016, the Swedish Supreme Court ruled that Wikimedia Sweden infringed on the copyright of artists of public artwork by creating a website and database of public artworks in Sweden, containing images of public artwork uploaded by the public.[20][21][22] Swedish copyright law contains an exception to the copyright holder's exclusive right to make their works available to the public that allows depictions of public artwork.[23]:2–5 The Swedish Supreme Court decided to take a restrictive view of this copyright exception.[23]:6 The Court determined that the database was not of insignificant commercial value, for both the database operator or those accessing the database, and that "this value should be reserved for the authors of the works of art. Whether the operator of the database actually has a commercial purpose is then irrelevant."[23]:6 The case was returned to a lower court to determine damages that Wikimedia Sweden owes to the collective rights management agency Bildkonst Upphovsrätt i Sverige (BUS), which initiated the lawsuit on behalf of artists they represent.[23]:2,7

Australia

In Australia, freedom of panorama is dealt with in the federal Copyright Act 1968, sections 65 to 68. Section 65 provides: "The copyright in a work ... that is situated, otherwise than temporarily, in a public place, or in premises open to the public, is not infringed by the making of a painting, drawing, engraving or photograph of the work or by the inclusion of the work in a cinematograph film or in a television broadcast". This applies to any "artistic work" as defined in paragraph (c) of section 10: a "work of artistic craftsmanship" (but not a circuit layout).[24]

However, "street art" may be protected by copyright.[25][26][27]

Section 66 of the Act provides exceptions to copyright infringement for photos and depictions of buildings and models of buildings.[24]

Canada

Section 32.2(1) of the Copyright Act (Canada) states the following:

It is not an infringement of copyright

(b) for any person to reproduce, in a painting, drawing, engraving, photograph or cinematographic work(i) an architectural work, provided the copy is not in the nature of an architectural drawing or plan, or(ii) a sculpture or work of artistic craftsmanship or a cast or model of a sculpture or work of artistic craftsmanship, that is permanently situated in a public place or building;

The Copyright Act also provides specific protection for the incidental inclusion of another work seen in the background of a photo. Photos that "incidentally and not deliberately" include another work do not infringe copyright.

Philippines

The Intellectual property Code of the Philippines (Republic Act No. 8923) makes no specific provision for freedom of panorama; §180.3 does make provision regarding "[t]he reproduction and communication to the public of literary, scientific or artistic works as part of reports of current events by means of photography, cinematography or broadcasting to the extent necessary for the purpose."[28] As of November 2020, Wikimedia Commons did not consider these exceptions sufficient for inclusion of such photographic images there but did note some specific provisions in other Philippine laws regarding copyrights related to buildings completed prior to particular dates.[29]

United Kingdom

Under UK law, freedom of panorama covers all buildings as well as most three-dimensional works such as sculptures that are permanently situated in a public place. The freedom does not generally extend to two-dimensional copyright works such as murals or posters. A photograph which makes use of the freedom may be published in any way without breaching copyright.

Section 62 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is broader than the corresponding provisions in many other countries, and allows photographers to take pictures of buildings, defined in section 4(2) as "any fixed structure, and a part of a building or fixed structure". There is no requirement that the building be in located a public place, nor does the freedom extend only to external views of the building.

Also allowed are photographs of certain artworks that are permanently situated in a public place or in premises open to the public, specifically sculptures, models for buildings, and "works of artistic craftsmanship". According to the standard reference work on copyright, Copinger and Skone James, the expression "open to the public" presumably includes premises to which the public are admitted only on licence or on payment.[30] Again, this is broader than 'public place', which is the wording in many countries, and there is no restriction to works that are located outdoors.

Under the local approach to copyright, "works of artistic craftsmanship" are defined separately from "graphic works", and the freedom of section 62 does not apply to the latter. "Graphic works" are defined in section 4 as any painting, drawing, diagram, map, chart or plan, any engraving, etching, lithograph, woodcut or similar work. Accordingly, photographs may not freely be taken of artworks such as murals or posters even if they are permanently located in a public place.

The courts have not established a consistent test for what is meant by a "work of artistic craftsmanship", but Copinger suggests that the creator must be both a craftsman and an artist.[31] Evidence of the intentions of the maker are relevant, and according to the House of Lords case of Hensher v Restawile [1976] AC 64, it is "relevant and important, although not a paramount or leading consideration" if the creator had the conscious purpose of creating a work of art. It is not necessary for the work to be describable as "fine art". In that case, some examples were given of typical articles that might be considered works of artistic craftsmanship, including hand-painted tiles, stained glass, wrought iron gates, and the products of high-class printing, bookbinding, cutlery, needlework and cabinet-making.

Other artworks cited by Copinger that have been held to fall under this definition include hand-knitted woollen sweaters, fabric with a highly textured surface including 3D elements, a range of pottery and items of dinnerware. The cases are, respectively, Bonz v Cooke [1994] 3 NZLR 216 (New Zealand), Coogi Australia v Hyrdrosport (1988) 157 ALR 247 (Australia), Walter Enterprises v Kearns (Zimbabwe) noted at [1990] 4 EntLR E-61, and Commissioner of Taxation v Murray (1990) 92 ALR 671 (Australia).

The Design and Artists Copyright Society and Artquest provide further information on UK freedom of panorama.[32][33]

Architectural Works

United States copyright law contains the following provision:

The copyright in an architectural work that has been constructed does not include the right to prevent the making, distributing, or public display of pictures, paintings, photographs, or other pictorial representations of the work, if the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place.

The definition of "architectural work" is a building,[35] which is defined as "humanly habitable structures that are intended to be both permanent and stationary, such as houses and office buildings, and other permanent and stationary structures designed for human occupancy, including but not limited to churches, museums, gazebos, and garden pavilions".[36]

Other Works

Nevertheless, the United States freedom of panorama does not cover other artistic works still covered by copyright, including sculptures. Usages of images of such works for commercial purposes may become copyright infringements.

One notable case of copyright infringement involving public artworks in the United States is Gaylord v. United States, No. 09-5044. This involved the United States Postal Service's use of an image of 14 out of 19 statues of soldiers in the Korean War Veterans Memorial for their commemorative stamp in the 50th anniversary of the Korean War armistice in 2003. USPS did not obtain permission from Frank Gaylord, sculptor of the said artistic work called The Column, for their use of the image on their stamp which cost 37 cents.[37] He filed a case against USPS in 2006 for their violation of his copyright over the said artistic work. Included in the case was former Marine John Alli who was the photographer of the said image of the sculpture. Eventually, an amicable settlement with Alli was reached when the photographer agreed to pay Gaylord a 10% royalty for any subsequent sales of his image of the sculpture.[38][39]

In a 2008 decision of the Court of Federal Claims, it was determined that USPS did not infringe Gaylord's copyright as their use complies with fair use. Nevertheless the court determined that The Column is not covered by the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act (AWCPA) as it is not an architectural work of art. The side of the sculptor appealed, and on February 25, 2010 the Federal Circuit reversed the earlier decision regarding fair use. The use of the image of The Column in the commemorative stamp by USPS cannot be considered as a fair use since it is not transformative in nature (the context and intended meaning in the stamp remained the same as that of the actual sculpture). The presence of the artistic work in the stamp is substantial, and this also fails fair use. The purpose of USPS over this use is considered commercial, because it earned $17 million from its sales of almost 48 million stamps bearing this image. The Federal Circuit upheld the earlier decision of the Court of Federal Claims that The Column is not a work of architecture.[37] On remand in 2011, the Court of Federal Claims awarded $5,000 in damages. Gaylord appealed the amount of the damages, and in 2012 the appeals court "remanded the case for a determination of the fair market value of the Postal Service’s infringing use".[40] In September 20, 2013 the Court of Federal Claims awarded a total of $684,844.94 worth of economic rights damage that was to be paid by USPS to Gaylord.[41][42]

Former USSR countries

Almost all countries from the former Soviet Union lack freedom of panorama. Exceptions are three countries whose copyright laws were amended recently. The first was Moldova in July 2010, when the law in question was approximated to EU standards.[43] Armenia followed in April 2013 with an updated Armenian law on copyright.[44] Freedom of panorama was partially adopted in Russia on October 1, 2014; from this day, one is allowed to take photos of buildings and gardens visible from public places, but that does not include sculptures and other 3-dimensional works.[45]

Two-dimensional works

The precise extent of this permission to make pictures in public places without having to worry about copyrighted works being in the image differs amongst countries.[1] In most countries, it applies only to images of three-dimensional works[46] that are permanently installed in a public place, "permanent" typically meaning "for the natural lifetime of the work".[47][48] In Switzerland, even taking and publishing images of two-dimensional works such as murals or graffiti is permitted, but such images cannot be used for the same purpose as the originals.[47]

Public space

Many laws have subtle differences in regard to public space and private property. Whereas the photographer's location is irrelevant in Austria,[1] in Germany the permission applies only if the image was taken from public ground, and without any further utilities such as ladders, lifting platforms, airplanes etc.[12] Under certain circumstances, the scope of the permission is also extended to actually private grounds, e.g. to publicly accessible private parks and castles without entrance control, however with the restriction that the owner may then demand a fee for commercial use of the images.[49]

In many Eastern European countries the copyright laws limit this permission to non-commercial uses of the images only.[50]

There are also international differences in the particular definition of a "public place". In most countries, this includes only outdoor spaces (for instance, in Germany),[12] while some other countries also include indoor spaces such as public museums (this is for instance the case in the UK[51] and in Russia).[52]

Anti-terrorism laws

Tension has arisen in countries where freedom to take pictures in public places conflicts with more recent anti-terrorism legislation. In the United Kingdom, the powers granted to police under section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000 have been used on numerous occasions to stop amateur and professional photographers from taking photographs of public areas. Under such circumstances, police are required to have "reasonable suspicion" that a person is a terrorist.[53] While the Act does not prohibit photography, critics have alleged that these powers have been misused to prevent lawful public photography.[54] Notable instances have included the investigation of a schoolboy,[55] a Member of Parliament[56] and a BBC photographer.[57][58] The scope of these powers has since been reduced, and guidance around them issued to discourage their use in relation to photography, following litigation in the European Court of Human Rights.[59]

See also

References

- Seiler, David (2006). "Gebäudefotografie in der EU – Neues vom Hundertwasserhaus". Photopresse. p. 16. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Rosnay, Mélanie Dulong de; Langlais, Pierre-Carl (February 16, 2017). "Public artworks and the freedom of panorama controversy: a case of Wikimedia influence". Internet Policy Review. 6 (1). doi:10.14763/2017.1.447. ISSN 2197-6775. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018.

- N.N. "Panoramafreiheit". Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2020. See also Article 5(3)(h) of 2001/29/EC.

- "The IPKat". ipkitten.blogspot.co.uk. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015.

- "Euromyths and Letters to the Editor: Europe is not banning tourist photos of the London Eye". European Commission in the UK. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015.

- "Consolidated Act on Copyright (Consolidated Act No. 1144 of October 23, 2014)" (PDF). WIPO Lex. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- Hull, Craig. "Freedom of Panorama – What It Means for Photography". Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "Denmark's icon... that we can't show you". The Local. August 16, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- Burgett, Gannon (August 20, 2014). "If You Try to Publish a Picture of this Statue in Denmark, You'd Better be Ready to Pay Up". PetaPixel. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "Article 5, section 11 of Code on Intellectual Property". Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- "Rules for the use of images of the viaduct". Viaduc de Millau | Un ouvrage, un patrimoine. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Seiler, David (June 24, 2001). "Fotografieren von und in Gebäuden". visuell. p. 50. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2020. See also: "§59 UrhG (Germany)" (in German). Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- "Rechtsprechung – BGH, 05.06.2003 - I ZR 192/00". dejure.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Spinelli, Luca. "Wikipedia cede al diritto d'autore". Punto Informatico. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Grillini, Franco. "Interrogazione - Diritto di panorama" [Interrogation - panorama right]. Grillini.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Scorza, Guido; Spinelli, Luca (March 3, 2007). "Dare un senso al degrado" (PDF). Rome. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 8, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Legge 22 aprile 1941 n. 633" (in Italian). Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Decreto Legislativo 22 gennaio 2004, n. 42" (in Italian). Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Taking photos of the Palace of Parliament can be considered illegal". Pandects dpVUE. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Falkvinge, Rick (April 4, 2016). "Supreme Court: Wikimedia violates copyright by posting its own photos of public, taxpayer-funded art". Privacy Online News. Los Angeles, CA, USA. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- "Wikimedia Sweden art map 'violated copyright'". BBC News. April 5, 2016. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- Paulson, Michelle (April 4, 2016). "A strike against freedom of panorama: Swedish court rules against Wikimedia Sverige". Wikimedia Foundation blog. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- Bildupphovsrätt i Sverige ek. för. v. Wikimedia Svierge (Supreme Court of Sweden 04-04-2016).Text

- Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)

- "Street Art & Copyright". Information Sheet G124v01. Australian Copyright Council. September 2014. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Street photographer's rights". Arts Law Information Sheet. Arts Law Centre of Australia. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Photographers & Copyright" (PDF) (17 ed.). Australian Copyright Council. January 2014. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

You will generally need permission to photograph other public art, such as murals.

- "Republic Act No. 8293 : Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines". Official Gazette of the Philippine Government. June 6, 1997.

- Copyright rules by territory/Philippines on Wikimedia Commons.

- Copinger and Skone James on Copyright. 1 (17th ed.). Sweet & Maxwell. 2016. paragraph 9-266.

- Copinger and Skone James on Copyright. 1 (17th ed.). Sweet & Maxwell. 2016. paragraph 3-129.

- "Sculpture and works of artistic craftmanship on public display". DACS. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- Lydiate, Henry (1991). "Advertising and marketing art: Copyright confusion". Artquest.

- "17 U.S. Code § 120 - Scope of exclusive rights in architectural works". Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- "17 U.S. Code § 101". Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- "37 CFR 202.11(b)". Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- "Gaylord v. United States, 595 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2010)" (PDF). U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index. U.S. Copyright Office. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

The appellate court held ... weighed against a fair use finding.

- D'Ambrosio, Dan (September 20, 2013). "Korea memorial sculptor wins copyright case". USA Today. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Rein, Lisa (February 10, 2015). "Court upholds $540,000 judgment against USPS for Korean War stamp". Washington Post. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Moore, Kimberly Ann (May 14, 2012). "Gaylord v. United States, 678 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2012)". CourtListener. Free Law Project. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

remand for a determination of the market value of the Postal Service's infringing use

- "Gaylord v. U.S." Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Wheeler, Thomas C. (September 20, 2013). "FRANK GAYLORD v. UNITED STATES, No. 06-539C" (PDF). United States Court of Federal Claims. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Eugene Stuart; Eduardo Fano; Linda Scales; Gerda Leonaviciene; Anna Lazareva (July 2010). "Intellectual Property Law and Policy. Law approximation to EU standards in the Republic of Moldova" (PDF). IBF International Consulting, DMI, IRZ, Nomisma, INCOM, Institute of Public Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "Legislation: National Assembly of RA" (in Armenian). parliament.am. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- "О внесении изменений в части первую, вторую и четвертую Гражданского кодекса Российской Федерации и отдельные законодательные акты Российской Федерации. Статья 3, cтраница 2". State Duma (in Russian). March 5, 2014. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- See e.g. Lydiate.

- Rehbinder, Manfred (2000). Schweizerisches Urheberrecht (3rd ed.). Berne: Stämpfli Verlag. p. 158. ISBN 3-7272-0923-2. See also: "§27 URG (Switzerland)". Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Dix, Bruno (February 21, 2002). "Christo und der verhüllte Reichstag". Archived from the original on July 22, 2002. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Decision of the German Federal Court in favour of the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten, December 17, 2010". Juris.bundesgerichtshof.de. December 17, 2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- See e.g. for Russia: Elst, Michiel (2005). Copyright, Freedom of Speech, and Cultural Policy in the Russian Federation. Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff. p. 432f. ISBN 90-04-14087-5.

- Lydiate, Henry. "Advertising and marketing art: Copyright confusion". Artquest. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2020. See also: "Section 62 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988". Office of Public Sector Information. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Elst p. 432, footnote 268. Also see article 1276 of part IV of the Civil Code Archived 2012-06-07 at the Wayback Machine (in force as of January 1, 2008), clarifying this.

- "Photography and Counter-Terrorism legislation". The Home Office. August 18, 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- Geoghegan, Tom (April 17, 2008). "Innocent photographer or terrorist?". BBC News. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- "Terrorism Act: Photography fears spark police response". Amateur Photographer Magazine. October 30, 2008. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- "Tory MP stopped and searched by police for taking photos of cycle path". Daily Telegraph. January 6, 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- Davenport, Justin (November 27, 2009). "BBC man in terror quiz for photographing St Paul's sunset". London: Evening Standard. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- "BBC man in terror quiz for photographing St Paul's sunset - News - London Evening Standard". October 23, 2012. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

- "Section 44 Terrorism Act". Liberty. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freedom of panorama. |

- Photographing public buildings, from the American Society of Media Photographers.

- Millennium Park Photography: The Official Scoop, The Chicagoist, February 17, 2005.

- MacPherson, Linda: Photographer's Rights in the UK.

- Newell, Bryce Clayton (2011). "Freedom of Panorama: A Comparative Look at International Restrictions on Public Photography". Creighton Law Review. 44: 405–427.