Indigenous intellectual property

Indigenous intellectual property[1] is an umbrella legal term used in national and international forums to identify indigenous peoples' claims of collective intellectual property rights to protect specific cultural knowledge of their groups.[2][3] It is a concept that has developed as an analog to predominantly western concepts of intellectual property law, and has most recently been promoted by the World Intellectual Property Organization, as part of a broader effort by the United Nations[4] to see the world's indigenous, intangible cultural heritage better valued and better protected against perceived, ongoing mistreatment.[5][6]

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Legal representation |

| Category |

International bodies such as the United Nations have become involved in the issue,[3] making more specific declarations that intellectual property also includes cultural property such as historical sites, artefacts, designs, language, ceremonies, and performing arts in addition to artwork and literature.[7][8]

Nation states across the world have experienced difficulties reconciling local indigenous laws and cultural norms with a predominantly western legal system, in many cases leaving indigenous peoples' individual and communal intellectual property rights largely unprotected.[9]

The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) has set out several goals around treaty law and intellectual property, with board member Professor Rebecca Tsosie stressing the importance of these property rights being held collectively, not by individuals:

The long-term goal is to actually have a legal system, and certainly a treaty could do that, that acknowledges two things. Number one, it acknowledges that indigenous peoples are peoples with a right to self-determination that includes governance rights over all property belonging to the indigenous people. And, number two, it acknowledges that indigenous cultural expressions are a form of intellectual property and that traditional knowledge is a form of intellectual property, but they are collective resources – so not any one individual can give away the rights to those resources. The tribal nations actually own them collectively.[10]

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), September 2007

At the United Nation's General Assembly's 61st session, on 13 September 2007, an overwhelming majority of members resolved to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[11] Regarding the intellectual property rights of indigenous peoples, the General Assembly recognized "..the urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples which derive from their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies...;"[12] reaffirmed "...that indigenous peoples possess collective rights which are indispensable for their existence, well-being and integral development as peoples...;"[13] and solemnly proclaimed as an agreed standard for member nations around the world:

Article 11: Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature.

States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.[14]

Article 24: Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals and minerals...[15]

Article 31: Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.In conjunction with indigenous peoples, States shall take effective measures to recognize and protect the exercise of these rights."[15]

"Traditional cultural expressions"

"Traditional cultural expressions" is a phrase used by the World Intellectual Property Organization to refer to "any form of artistic and literary expression in which traditional culture and knowledge are embodied. They are transmitted from one generation to the next, and include handmade textiles, paintings, stories, legends, ceremonies, music, songs, rhythms and dance."[16]

"Traditional cultural expressions" can include designs and styles, which means that applying traditional Western-style international copyright laws – which apply to a specific work, rather than a style – can be problematic. Indigenous customary law often treats such concepts differently, and may apply restrictions upon the use of underlying styles and concepts.[16]

Criticism

Critics of the movement for granting Indigenous Intellectual Property Rights note that the indefinite duration of such a context is "unorthodox and unmanageable" within the current IP legal structure.[17]

Claims and declarations regarding Indigenous Intellectual Property

A number of Native American and First Nations communities have issued tribal declarations over the past 35 years. In the lead up to and during the United Nations International Year for the World's Indigenous Peoples (1993),[18] then during the following United Nations Decade of the World's Indigenous Peoples (1995–2004),[4] a number of conferences of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous specialists were held in different parts of the world, resulting in a number of unified declarations and statements identifying, explaining, refining, and defining "indigenous intellectual property" though the legal weight of most has yet to be tested.

Intertribal coalitions in North America

Since the 1970s, Intertribal groups in North American have organized demonstrations against non-Native use of Native American cultural elements; such as the sale of products and services allegedly derived from Indigenous knowledge:[19][20]

"It is a very alarming trend. So alarming that it came to the attention of an international and intertribal group of medicine people and spiritual leaders called the Circle of Elders. They were highly concerned with these activities and during one of their gatherings addressed the issue by publishing a list of Plastic Shamans in Akwesasne Notes, along with a plea for them to stop their exploitative activities. One of the best known Plastic Shamans, Lynn Andrews, has been picketed by the Native communities in New York, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Seattle and other cities.[20]

Resolution of the 5th Annual Meeting of the Traditional Elders Circle, October 1980

Before ceremonies and ceremonial knowledge were affirmed as protected intellectual property by the U.N. General Assembly,[7] smaller coalitions of Indigenous cultural leaders met to issue declarations about protection of ceremonial knowledge.[21][22][23] In 1980, spiritual leaders of the Northern Cheyenne, Navajo, Hopi, Muskogee, Chippewa-Cree, Haudenosaunee and Lakota Nations met on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana,[21] and issued a resolution that:

These [non-Native] individuals are gathering non-Indian people as followers who believe they are receiving instructions of the original people. We, the Elders and our representatives sitting in Council, give warning to these non-Indian followers that it is our understanding this is not a proper process, that the authority to carry these sacred objects is given by the people...[21]

Declaration of Belém, July 1988

The first international congress of the International Society of Ethnobiology involving scientists, environmentalists and Indigenous peoples met at Belém, Brazil. They identified themselves collectively as 'ethnobiologists', and announced that (amongst other matters) since "Indigenous cultures around the world are being disrupted and destroyed.":

"Mechanisms [ought to] be established by which indigenous specialists are recognized as proper Authorities and are consulted in all programs affecting them, their resources and their environment"

"Procedures must be developed to compensate native peoples for the utilization of their knowledge and their biological resources"[24]

Kari-Oca Declaration and Indigenous Peoples Earth Charter, May 1992

The Kari-Oca Declaration and charter was first affirmed in Brazil in May 1992, and then re-affirmed in Indonesia, in June 2002. Ratifying the document were Indigenous peoples from the Americas, Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe and the Pacific who, at Kari-Oca Villages, united in one voice to collectively express their serious concern at the way the world was exploiting the natural resources upon which indigenous peoples depend.

Specific reference is made within the Indigenous Peoples Earth Charter to perceived abuses of indigenous people's intellectual and cultural properties.[25] Under the heading,"Culture, Science and Intellectual Property", amongst other matters, it is asserted:[26]

99: The usurping of traditional medicines and knowledge from Indigenous peoples should be considered a crime against peoples...

102: As creators and carriers of civilizations which have given and continue to share knowledge, experience, and values with humanity, we require that our right to intellectual and cultural properties be guaranteed and that mechanisms for each be in favour of our peoples...

104: The protection, norms and mechanism of artistic and artisan creation of our peoples must be established and implemented in order to avoid plunder, plagiarism, undue exposure, and use...[6]

Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality, June 1993

At the Lakota Summit V, an international gathering of US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations, about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the Lakota unanimously passed a "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality."[22][23] Representatives affirmed a zero-tolerance policy on the exploitation of Lakota, Dakota and Nakota ceremonial knowledge.[22][23]

Whereas we are conveners of an ongoing series of comprehensive forums on the abuse and exploitation of Lakota spirituality; and

Whereas we represent the recognized Lakota leaders, traditional elders, and grassroots advocates of the Lakota people; and ...

Whereas non-Indian charlatans and "wannabes" are selling books that promote systematic colonization of our Lakota spirituality; and

Whereas this exponential exploitation of our Lakota spiritual traditions requires that we take immediate action to defend our most precious Lakota spirituality from further contamination, desecration and abuse; ...[22][23]

6. We urge traditional people, tribal leaders, and governing councils of all other Indian Nations, as well as all national Indian organizations, to join us in calling for an immediate end to this rampant exploitation of our respective American Indian sacred traditions by issuing statements denouncing such abuse; for it is not the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people alone whose spiritual practices are being systematically violated by non-Indians.7. We urge all our Indian brothers and sisters to act decisively and boldly in our present campaign to end the destruction of our sacred traditions, keeping in mind that our highest duty as Indian people: to preserve the purity of our precious traditions for future generations, so that our children and our children's children will survive and prosper in the sacred manner intended for each of our respective peoples by our Creator.[22][23]

Mātaatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples, June 1993

On 18 June 1993, 150 delegates from fourteen countries, including indigenous representatives from Japan (Ainu), Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, India, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Surinam, United States and Aotearoa (New Zealand) met at Whakatane (Bay of Plenty region of New Zealand). The assembly affirmed Indigenous peoples' knowledge is of benefit to all humanity; recognised Indigenous peoples are willing to offer their knowledge to all humanity provided their fundamental rights to define and control this knowledge is protected by the international community; insisted the first beneficiaries of Indigenous knowledge must be the direct Indigenous descendants of such knowledge; and declared all forms of exploitation of Indigenous knowledge must cease.[27]

Under Section 2 of their declaration they specifically ask State, National and International Agencies to:[27]

2.1: Recognise that Indigenous peoples are the guardians of their customary knowledge and have the right to protect and control dissemination of that knowledge.

2.2: Recognise that Indigenous peoples also have the right to create new knowledge based on cultural tradition"

2.3: Accept that the cultural and intellectual property rights of Indigenous peoples are vested with those who created them.[6]

Julayinbul Statement on Indigenous Intellectual Property Rights, November 1993

This declaration arose out of a meeting of Indigenous and non-Indigenous specialists, who, at Jingarrba, in north-eastern Australia, agreed Indigenous intellectual property rights are best determined from within the customary laws of the Indigenous groups' themselves.[28] Within the declaration, Indigenous customary laws are (re)named 'Aboriginal common laws', and it is insisted these laws must be acknowledged and treated as equal to any other systems of law:[29]

...Indigenous Peoples and Nations reaffirm their right to define for themselves their own intellectual property, acknowledging...the uniqueness of their own particular heritage.

...Indigenous Peoples and Nations...declare that we...are willing to share [our intellectual property] with all humanity provided that our fundamental rights to define and control this property are recognised by the international community...

Aboriginal intellectual property, within Aboriginal Common Law, is an inherent, inalienable right which cannot be terminated, extinguished, or taken... Any use of the intellectual property of Aboriginal Nations and Peoples may only be done in accordance with Aboriginal Common Law, and any unauthorised use is strictly prohibited."[6][30]

Hopi and Apache opt-out from American museums

In 1994 a number of Native American tribal organizations demanded that museums remove certain materials from exhibition and access to the public. They cited the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) as the legal basis for these complaints. Their position was that they would only permit such uses selectively and with express permission of the living relatives of the human remains and grave goods the museums wished to exhibit.[31] Vernon Masayesva, CEO of the Hopi Tribe, and a consortium of Apache tribes demanded a number of American museums end all public exhibition of, and access to, materials from their tribal cultures; including "images, text, ceremonies, music, songs, stories, symbols, beliefs, customs, ideas, concepts and ethnographic field-notes, feature films, historical works, and any other medium in which their culture may appear literally, imagined, expressed, parodied or embellished."[31] Many Apache tribes such as the White Mountain Apache Tribe have also asked for the return of Puebloan artifacts and bodies that were taken off of their land by various collectors overtime.[32]

Santa Cruz de la Sierra Statement on Intellectual Property, September 1994

A regional meeting was held at Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia where indigenous peoples from the South America's concerned about the way internationally prevailing intellectual property systems and regimes appeared to be favouring the appropriation of indigenous peoples' knowledge and resources for commercial purposes, agreed:[33]

For members of indigenous peoples, knowledge and determination of the use of resources are collective and intergenerational. No...individuals or communities, nor the Government, can sell or transfer ownership of [cultural] resources which are the property of the people and which each generation has an obligation to safeguard for the next.

Work must be conducted on the design of a protection and recognition system which is in accordance with ..our own conception, and mechanisms must be developed .. which will prevent appropriation of our resources and knowledge.

There must be appropriate mechanisms for maintaining and ensuring the right of Indigenous peoples to deny indiscriminate access to the [cultural] resources of our communities or peoples and making it possible to contest patents or other exclusive rights to what is essentially Indigenous.[33]

Tambunan Statement on the Protection and Conservation of Indigenous Knowledge, February 1995

Indigenous people of Asia met at Tambunan, Sabah, East Malaysia, to assert rights of self-determination, and to express concern about, and fear of, the threat unfamiliar 'western' intellectual property rights systems may pose to them. It was agreed:[34]

For the Indigenous peoples of Asia, the intellectual property rights system is not only a very new concept but it is also very western...[W]ith [western style] intellectual property rights, alien laws will be devised to exploit the Indigenous knowledge and [cultural] resources of the Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples are not benefiting from the intellectual property rights system. Indigenous knowledge and [cultural] resources are being eroded, exploited and/or appropriated by outsiders in the likes of transnational corporations, institutions, researchers, and scientists who are after profits and benefits gained..[34]

Suva Statement on Indigenous Peoples Knowledge and Intellectual Property Rights, April 1995

Participants from the independent countries and "nonautonomous colonised territories" of the Pacific region met in Suva, Fiji to discuss internationally dominant intellectual property rights regimes, and at that meeting they resolved to support the Kari Oca, Mataatua, Julayinbul, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, and Tambunan initiatives[35](above). In particular participants:[35]

Reaffirm[ed] that imperialism is perpetuated through [western] intellectual property rights systems...

Declare[d] Indigenous peoples are willing to share our knowledge with humanity provided we determine when, where and how it is used: at present the international system does not recognise or respect our past, present and potential contribution...

Seek[s] repatriation of Indigenous peoples [cultural] resources already held in external collections, and seek[s] compensation and royalties from commercial developments resulting from these resources

...encourage[s]...governments...to protest against any General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade provisions which facilitate the expropriation of Indigenous peoples' knowledge and resources...[to instead] incorporate the concerns of Indigenous peoples...into legislation...

[Seek to] Strengthen the capacities of Indigenous peoples to maintain their oral traditions, and encourage initiatives by Indigenous peoples to record their knowledge .. according to their customary access procedures."Urge universities, churches, government, non-government organizations, and other institutions to reconsider their roles in the expropriation of Indigenous people's knowledge and resources and to assist in their return to their rightful owners."[35]

Kimberley Declaration, August 2002

(Kimberley, South Africa August 2002)

Indigenous people from around the world attended an international indigenous peoples' summit on sustainable development in Khoi-San Territory, Kimberley, South Africa, where they reaffirmed previous declarations and statements (above), and, among other matters, declared:

Our traditional knowledge systems must be respected, promoted and protected; our collective intellectual property rights must be guaranteed and ensured. Our traditional knowledge is not in the public domain; it is collective, cultural and intellectual property protected under our customary law. Unauthorized use and misappropriation of traditional knowledge is theft.[6]

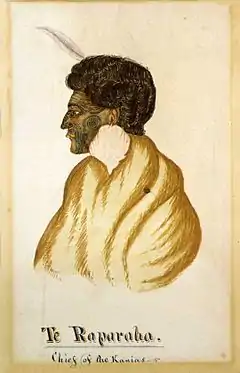

Māori Ka Mate haka

Since the 19th century, Māori-style Hakas have been popularly-used by New Zealanders as a cheer at sporting events; especially for New Zealand national teams. Between 1998 and 2006, the Ngāti Toa iwi attempted to trademark the Ka Mate haka and to forbid its use by commercial organisations without their permission.[36][37] The Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand turned their claim down in 2006, since Ka Mate had achieved wide recognition in New Zealand and abroad as representing New Zealand as a whole and not a particular trader.[38] In 2009, as a part of a wider settlement of grievances, the New Zealand government agreed to:

- "...record the authorship and significance of the haka Ka Mate to Ngāti Toa and ... work with Ngāti Toa to address their concerns with the haka... [but] does not expect that redress will result in royalties for the use of Ka Mate or provide Ngāti Toa with a veto on the performance of Ka Mate...".[39][40]

However, a survey of nineteenth-century New Zealand newspapers found Ka Mate was used by tribes from other parts of New Zealand, and was generally described by them as being an ancient peacekeeping song, from eras long before its appropriation by the Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha. When Ngāti Toa authorities were asked for evidence that Ka Mate was of Ngāti Toa authorship, they were unable to provide any.[41]

The Māori and Lego's Bionicle

In 2001 a dispute concerning the popular LEGO toy-line "Bionicle" arose between Danish toymaker Lego Group and several Māori tribal groups (fronted by lawyer Maui Solomon) and members of the on-line discussion forum (Aotearoa Cafe). The Bionicle product line allegedly used many words appropriated from Māori language, imagery and folklore. The dispute ended in an amicable settlement. Initially Lego refused to withdraw the product, saying it had drawn the names from many cultures, but later agreed that it had taken the names from Māori and agreed to change certain names or spellings to help set the toy-line apart from the Māori legends. This did not prevent the many Bionicle users from continuing to use the disputed words, resulting in the popular Bionicle website BZPower coming under a denial-of-service attack for four days from an attacker using the name Kotiate.[42]

"Māori" cigarettes

In 2005 a New Zealander in Jerusalem discovered that the Phillip Morris cigarette company had started producing a brand of cigarette in Israel called the "L & M Maori mix".[43] In 2006, the head of Phillip Morris, Louis Camilleri, issued an apology to Māori: "We sincerely regret any discomfort that was caused to Māori people by our mistake and we won't be repeating it."[44]

See also

References

Notes

- Ann Marie Sullivan, Cultural Heritage & New Media: A Future for the Past, 15 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 604 (2016)

- RAINFOREST ABORIGINAL NETWORK (1993) Julayinbul: Aboriginal Intellectual and Cultural Property Definitions, Ownership and Strategies for Protection. Rainforest Aboriginal Network. Cairns. Page 65

- Working Group on Indigenous Populations, accepted by the United Nations General Assembly, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine; UN Headquarters; New York City (13 September 2007): Article 31: "Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions."

- OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (2007). "Indigenous peoples". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights. Geneva. Archived from the original (WEB PAGE) on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- DODSON, Page 12.

- WIPO Database of Indigenous Intellectual Property Codes, Guidelines, and Practices Accessed 28 November 2007. Archived 2 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Working Group on Indigenous Populations, accepted by the United Nations General Assembly, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine; UN Headquarters; New York City (13 September 2007): Article 11: "Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature."[bold added]

- OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (2007). "Indigenous peoples". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights. Geneva. Archived from the original (WEB PAGE) on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

The Declaration addresses both individual and collective rights; cultural rights and identity; rights to education, health, employment, language, and others.

- Hadley, Marie (2009). "Lack of Political Will or Academic Inertia? - The need for non-legal responses to the issue of Indigenous art and copyright". Alternative Law Journal. Melbourne: Legal Service Bulletin Co-operative Ltd. 34 (3): 152–156. doi:10.1177/1037969X0903400302. S2CID 148729597.

- Tsosie, Rebecca (25 June 2017). "Current Issues in Intellectual Property Rights to Cultural Resources". Native American Rights Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (2007). "Declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights. Geneva. Archived from the original (WEB PAGE) on 24 November 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Page 2

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Page 3

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Page 5

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Page 7

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad; et al. (2015), ENGAGING - A Guide to Interacting Respectfully and Reciprocally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, and their Arts Practices and Intellectual Property (PDF), Australian Government: Indigenous Culture Support, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2016

- Centre for International Governance Innovation position paper p5

- WATSON, Irene (1992). "1993: International Year for Indigenous Peoples". Aboriginal Law Bulletin. AustLII. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- Hagan, Helene E. "The Plastic Medicine People Circle." Archived 5 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Sonoma Free County Press. Accessed 31 January 2013: "Shequish...came to the attention of Native American people two years ago as an impostor who pretended to have Shumash ancestry. I received a personal telephone call and a letter from the Chairman of a Shumash group south of Monterey. This phone call and a letter followed a Council meeting in which Shumash people took the decision to put a stop to Shequish Ohoho's activities in the Bay area as an 'Indian woman.' A group of real Indian women of San Francisco led a protest against Shequish and effectively terminated her money making seminars and ceremonies in this area. Her real name and background are known to California Indians who have denied her any tribal affiliation."

- Sieg, Katrin, Ethnic Drag: Performing Race, Nation, Sexuality in West Germany; University of Michigan Press (20 August 2002) p.232

- Yellowtail, Tom, et al; "Resolution of the 5th Annual Meeting of the Traditional Elders Circle" Northern Cheyenne Nation, Two Moons' Camp, Rosebud Creek, Montana; 5 October 1980

- Mesteth, Wilmer, et al (10 June 1993) "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." "At the Lakota Summit V, an international gathering of US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota (LDN) Nations, about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the LDN peoples unanimously passed a "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." The following declaration was unanimously passed."

- Taliman, Valerie (1993) "Article On The 'Lakota Declaration of War'."

- "Declaration of Belem". 1988. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- FOURMILE, Henrietta (1996) "Making things work: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Involvement in Bioregional Planning" in Approaches to bioregional planning. Part 2. Background Papers to the conference; 30 October – 1 November 1995, Melbourne; Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories. Canberra. p.235

- FOURMILE pages 260–261

- FOURMILE page 262

- FOURMILE page 236

- FOURMILE pages 264

- RAINFOREST ABORIGINAL NETWORK Pages 9–13

- Brown, Michael F. (April 1998). "Can Culture Be Copyrighted?" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 39 (2): 193–222. doi:10.1086/204721. JSTOR 10.1086/204721.

- Hoerig, Karl A. (March 2010). "FROM THIRD PERSON TO FIRST: A Call for Reciprocity Among Non-Native and Native Museums". Museum Anthropology. 33 (1): 62–74. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01076.x.

- FOURMILE 1996: Pages 266–267.

- FOURMILE 1996: Pages 268–269.

- FOURMILE 1996: Pages 270–272.

- "All Blacks fight to keep haka". BBC News. 16 July 2000. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Iwi threatens to place trademark on All Black haka". The New Zealand Herald. 22 May 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Iwi claim to All Black haka turned down". The New Zealand Herald. 2 July 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Ngāti Toa Rangatira Letter of Agreement Archived 21 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "New Zealand Maori win haka fight". BBC News. 11 February 2009.

- "Archer J.H. (2009) Ka Mate; its origins, development and significance" (PDF).

- Griggs, Kim (21 November 2002). "Lego Site Irks Maori Sympathizer". Wired.

- "Disgust over 'Maori' brand cigarettes". TVNZ. 12 December 2005. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- Stokes, Jon (29 April 2006). "Tobacco giant apologises to Maori". The New Zealand Herald.

Bibliography

- DODSON, Michael (2007). "Report of the Secretariat on Indigenous traditional knowledge" (PDF). Report to the United Nation's Economic and Social Council's Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Sixth Session, New York, 14–25 May. United Nation's Economic and Social Council. New York. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- DRAHOS, Peter (2001). "The Universality of Intellectual Property Rights: Origins and Development". World Intellectual Property Organization. Geneva. Archived from the original (DOC) on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- JONES, Peter (2008). "Intellectual Property, Indigenous Peoples, and the Law". Indigenous Peoples, Issues & Resources Website. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY (2007). "United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANISATION (2001). "Intellectual Property Needs and Expectations of Traditional Knowledge Holders". WIPO Report on Fact-finding Missions on Intellectual Property and Traditional Knowledge (1998–1999). World Intellectual Property Organization. Geneva. Archived from the original on 12 February 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

External links

- WIPO Database of Indigenous Intellectual Property Codes, Guidelines, and Practices

- Indigenous Peoples and Intellectual Property: Resource Database

- Intellectual property issues in cultural heritage

- Protecting Indigenous Traditional Cultural Expressions

- Indigenous/Traditional Knowledge & Intellectual Property