GNLY

Granulysin (GNLY) is a protein which is a member of saposin‐like protein family (SAPLIP) because of its structural and sequence homology to proteins containing saponin domain.[3][4] In humans it is encoded by the GNLY gene.[4] However, humans are not the only one who possess this kind of SAPLIP as its orthologs can be found in many different species. Examples of these orthologs are Amoebapore A, B and C (found in Entamoeba histolytica), Bovine lysin (found in cows), NK-lysin (found in pigs) and many more.[3][5] Of note, rodents do not possess any GNLY ortholog.[6]

| GNLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | GNLY, 519, D2S69E, LAG-2, LAG2, NKG5, TLA519, granulysin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 188855 HomoloGene: 136805 GeneCards: GNLY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Entrez |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ensembl |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UniProt |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

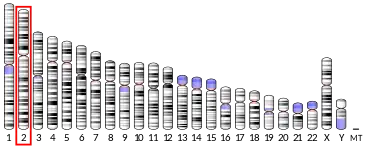

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 2: 85.69 – 85.7 Mb | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PubMed search | [2] | n/a | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

GLNY has two forms: longer 15 kDa GNLY and shorter 9 kDa GNLY. The 9 kDa GLNY is best known for its ability to kill microbes like Plasmodium vivax, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Candida by assembling itself into a pore which disrupts the pathogen's membrane. This ability makes it an antimicrobial peptide.[6] Its expression is restricted to cytotoxic immune cells like cytotoxic T cells, NK cells, NKT cells and γδ T cells. However exceptions can be found as for example presence of GNLY in regulatory T cells.[7]

Structure

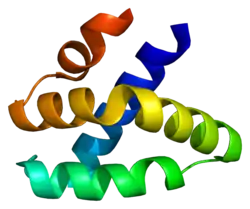

The 15 kDa GNLY is a 145 amino acid long protein which has two cleavage sides at its C-terminus and N-terminus which also contains a signal peptide which is generally important for protein trafficking within cells.[6] Both of these sides are cleaved by unknown enzyme in lower pH of cytotoxic granules which protects the cell from possible harm by active 9 kDa form of GNLY.[7][8] So far its 3D structure has not been solved.

The 9 kDa GNLY is a 74 amino acid long protein which unlike its longer counterpart has an antimicrobial activity. It consist of 5 α-helices and similarly to other antimicrobial peptides like human α and β-defensins, it is also positively charged.[6][7] This allows it to bind specifically to a negatively charged surface of the above mentioned pathogens. However, the entire protein is not needed for pathogen lysis. The α-helices 2 and 3 alone are enough to commence the lysis of a pathogen as the loop which connects them contains arginines which are also conserved in NK-lysis and they are important for the function of both GNLY and NK-lysin.[7]

Gene expression

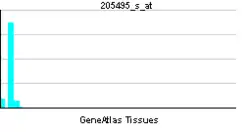

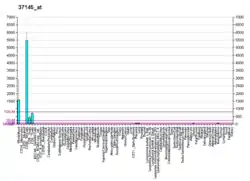

GNLY gene is located on human chromosome 2[4] and although its transcription is regulated by as of now unknown trancsription factors, it is clear that its expression is strictly regulated bacause under normal circumstances only NK cells express it constitutively.[6][8] All the other above mentioned cells need to be activated in order to produce GNLY. High expression can be seen in subset of skin NK cells and so called decidual NK cells which are located in placenta.[6][7] The decidual NK cells with probably the highest expression level of GNLY are also the only one which have GNLY located in its cytoplasm outside of the cytotoxic granules.[9]

Function

15 kDa GNLY

The 15 kDa GNLY was originally thought to only be an inactive precursor of antimicrobial 9 kDa GNLY. However, this has been recently challenged. 15 kDa is located in its own granules and its release is govern by PKC and not by Ca2+ like the cytotoxic granules with 9 kDa GNLY. Unlike 9 kDa GNLY it is also released constitutively and according to the new evidence it is able to work as an alarmin, also known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP), which are molecules capable of starting an inflammatory response. More precisely, 15 kDa GNLY is capable of initiating differentiation of monocyte into dendritic cells and dendritic cells maturation as shown by increased CD80, CD83 and CD86 expression. It is also able to act as a chemoattractant for different cells like NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, helper T cells and in higher concertation immature dendritic cells. Interestingly lower concertation attracts mature dendritic cells but higher repels them. This might help dendritic cells to leave the side of infection as the inflammation progresses and travel to lymph nodes to activate T cells.[7][10]

9 kDa GNLY

As mentioned above 9 kDa GNLY is an antimicrobial peptide which is created by cleavage of 15 kDa GNLY and stored in cytotoxic granules along with perforin and granzymes. 9 kDa GNLY has the ability to create pores in microbes which in some cases can be enough to kill the pathogen.[7][11] Important is that GNLY targets the microbes membranes specifically because it binds to apart from phosphoethanolamine also to cardiolipin which is present in bacterial membrane but not in human membrane. Its bond is also inhibited by cholesterol which is present in human cells but not in pathogen's cell. This all makes GNLY 1000 times less effective in pore formation in human cells than in microbe cells. However, the precise mechanisms of pore formation is not yet fully understood.[7][8]

Although GNLY is able to kill pathogens by itself, usually, it cooperates with other proteins from cytotoxic granules mainly with granzymes. When a cytotoxic cell discovers any infected cell the content of cytotoxic granules is released by receptor-mediated exocytosis. Perforin which unlike GNLY binds preferably to cholesterol rich membranes permeabilizes the infected cell and allows enter of GNLY and granzymes. GNLY then creates pores in pathogen membranes so granzymes can get inside the pathogen where it causes so called microbial programed cell death, also known as microptosis.[6][7][8]

Granzymes usually also cause apoptosis of the infected cell through initiation of caspase cascade. However apoptosis can also be started by GNLY. The reason is presence of cardiolipin in mitochodrial membranes which allows GNLY to create pores in the membrane and causing a release of molecules like cytochrom c which also leads to the process of apoptosis.[8]

GNLY in diseases

Granulysin has been implicated to play a role in a myriad of diseases. This role can be positive and negative.[3] The negative role is probably due to extremely high concentrations which can cause lysis even of human cells. These high concentrations have been found in blisters of patients suffering from Stevens–Johnson syndrome or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis.[11] On the other hand, GNLY seems to play positive role in cancer as transgenic mice expressing human GNLY had slightly better survival chance when infected with for wild type lethal dose of C6VL lymphoma cells although it had no effect when mice were infected with another kind of lymphoma.[12] Despite these unclear results from mice its importance is shown by the fact that high GNLY expression during some cancers for example colorectal and hematological is connected with better prognosis.[11] However, since only extremely high concentrations like in above mentioned diseases can permebilize human cells, it is unlikely that the positive correlation is due to pore forming ability of 9 kDa GNLY. More likely, the high GNLY expression shows that there is little exhaustion of immune system and furthermore, the chemoattractant ability of 15 kDa GNLY enables the attraction of more immune cells to the tumor.[6][7]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000115523 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Krensky AM, Clayberger C (March 2009). "Biology and clinical relevance of granulysin". Tissue Antigens. 73 (3): 193–8. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01218.x. PMC 2679253. PMID 19254247.

- "Entrez Gene: GNLY granulysin".

- Chen J, Huddleston J, Buckley RM, Malig M, Lawhon SD, Skow LC, et al. (December 2015). "Bovine NK-lysin: Copy number variation and functional diversification". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (52): E7223-9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519374113. PMC 4702975. PMID 26668394.

- Dotiwala F, Lieberman J (October 2019). "Granulysin: killer lymphocyte safeguard against microbes". Current Opinion in Immunology. Allergy and hypersensitivity • Host pathogens. 60: 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2019.04.013. PMC 6800608. PMID 31112765.

- Sparrow E, Bodman-Smith MD (January 2020). "Granulysin: The attractive side of a natural born killer". Immunology Letters. 217: 126–132. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2019.11.005. PMID 31726187.

- Liu X, Lieberman J (April 2020). "Knocking 'em Dead: Pore-Forming Proteins in Immune Defense". Annual Review of Immunology. 38 (1): 455–485. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-111319-023800. PMC 7260445. PMID 32004099.

- Crespo ÂC, Mulik S, Dotiwala F, Ansara JA, Sen Santara S, Ingersoll K, et al. (September 2020). "Decidual NK Cells Transfer Granulysin to Selectively Kill Bacteria in Trophoblasts". Cell. 182 (5): 1125–1139.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.019. PMID 32822574.

- Deng A, Chen S, Li Q, Lyu SC, Clayberger C, Krensky AM (May 2005). "Granulysin, a cytolytic molecule, is also a chemoattractant and proinflammatory activator". Journal of Immunology. 174 (9): 5243–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5243. PMID 15843520.

- Martinez-Lostao L, de Miguel D, Al-Wasaby S, Gallego-Lleyda A, Anel A (2015-08-01). "Death ligands and granulysin: mechanisms of tumor cell death induction and therapeutic opportunities". Immunotherapy. 7 (8): 883–2. doi:10.2217/imt.15.56. PMID 26314314.

- Huang LP, Lyu SC, Clayberger C, Krensky AM (January 2007). "Granulysin-mediated tumor rejection in transgenic mice". Journal of Immunology. 178 (1): 77–84. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.77. PMC 2664664. PMID 17182542.

Further reading

- Krista Conger. Grant to fund research into preventing bioterrorism, Stanford Report, November 12, 2003.

- Krensky AM, Clayberger C (August 2005). "Granulysin: a novel host defense molecule". American Journal of Transplantation. 5 (8): 1789–92. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00970.x. PMID 15996224. S2CID 19946195.

- Walch M, Dotiwala F, Mulik S, Thiery J, Kirchhausen T, Clayberger C, et al. (June 2014). "Cytotoxic cells kill intracellular bacteria through granulysin-mediated delivery of granzymes". Cell. 157 (6): 1309–1323. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.062. PMC 4090916. PMID 24906149.

- da Silva AP, Unks D, Lyu SC, Ma J, Zbozien-Pacamaj R, Chen X, et al. (May 2008). "In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activity of granulysin-derived peptides against Vibrio cholerae". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 61 (5): 1103–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn058. PMC 2664651. PMID 18310138.

- Chung WH, Hung SI, Yang JY, Su SC, Huang SP, Wei CY, et al. (December 2008). "Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". Nature Medicine. 14 (12): 1343–50. doi:10.1038/nm.1884. PMID 19029983. S2CID 2068160.

- Peña SV, Krensky AM (April 1997). "Granulysin, a new human cytolytic granule-associated protein with possible involvement in cell-mediated cytotoxicity". Seminars in Immunology. 9 (2): 117–25. doi:10.1006/smim.1997.0061. PMID 9194222.

- Krensky AM (February 2000). "Granulysin: a novel antimicrobial peptide of cytolytic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells". Biochemical Pharmacology. 59 (4): 317–20. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00177-X. PMID 10644038.

- Donlon TA, Krensky AM, Clayberger C (1990). "Localization of the human T lymphocyte activation gene 519 (D2S69E) to chromosome 2p12----q11". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 53 (4): 230–1. doi:10.1159/000132938. PMID 2209093.

- Yabe T, McSherry C, Bach FH, Houchins JP (October 1990). "A cDNA clone expressed in natural killer and T cells that likely encodes a secreted protein". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 172 (4): 1159–63. doi:10.1084/jem.172.4.1159. PMC 2188624. PMID 2212946.

- Houchins JP, Kricek F, Chujor CS, Heise CP, Yabe T, McSherry C, Bach FH (1993). "Genomic structure of NKG5, a human NK and T cell-specific activation gene". Immunogenetics. 37 (2): 102–7. doi:10.1007/BF00216832. PMID 8423048. S2CID 24229734.

- Peña SV, Hanson DA, Carr BA, Goralski TJ, Krensky AM (March 1997). "Processing, subcellular localization, and function of 519 (granulysin), a human late T cell activation molecule with homology to small, lytic, granule proteins". Journal of Immunology. 158 (6): 2680–8. PMID 9058801.

- Hanson DA, Kaspar AA, Poulain FR, Krensky AM (May 1999). "Biosynthesis of granulysin, a novel cytolytic molecule". Molecular Immunology. 36 (7): 413–22. doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(99)00063-2. PMID 10449094.

- Kaspar AA, Okada S, Kumar J, Poulain FR, Drouvalakis KA, Kelekar A, et al. (July 2001). "A distinct pathway of cell-mediated apoptosis initiated by granulysin". Journal of Immunology. 167 (1): 350–6. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.350. PMID 11418670.

- Kitamura N, Koshiba M, Horie O, Ryo R (2002). "Expression of granulysin mRNA in the human megakaryoblastic leukemia cell line CMK". Acta Haematologica. 108 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1159/000063061. PMID 12145461. S2CID 43475285.

- Ma LL, Spurrell JC, Wang JF, Neely GG, Epelman S, Krensky AM, Mody CH (November 2002). "CD8 T cell-mediated killing of Cryptococcus neoformans requires granulysin and is dependent on CD4 T cells and IL-15". Journal of Immunology. 169 (10): 5787–95. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5787. PMID 12421959.

- Ericson KG, Fadeel B, Andersson M, Gudmundsson GH, Gürgey A, Yalman N, et al. (January 2003). "Sequence analysis of the granulysin and granzyme B genes in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis". Human Genetics. 112 (1): 98–9. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0841-0. PMID 12483306. S2CID 23973452.

- Anderson DH, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Ernst W, Modlin R, Krensky A, Eisenberg D (January 2003). "Granulysin crystal structure and a structure-derived lytic mechanism". Journal of Molecular Biology. 325 (2): 355–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.5540. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01234-2. PMID 12488100.

- Gansert JL, Kiessler V, Engele M, Wittke F, Röllinghoff M, Krensky AM, et al. (March 2003). "Human NKT cells express granulysin and exhibit antimycobacterial activity". Journal of Immunology. 170 (6): 3154–61. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3154. PMID 12626573.

- Ogawa K, Takamori Y, Suzuki K, Nagasawa M, Takano S, Kasahara Y, et al. (July 2003). "Granulysin in human serum as a marker of cell-mediated immunity". European Journal of Immunology. 33 (7): 1925–33. doi:10.1002/eji.200323977. PMID 12884856.

- Kotsch K, Mashreghi MF, Bold G, Tretow P, Beyer J, Matz M, et al. (June 2004). "Enhanced granulysin mRNA expression in urinary sediment in early and delayed acute renal allograft rejection". Transplantation. 77 (12): 1866–75. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000131157.19937.3F. PMID 15223905. S2CID 31769483.