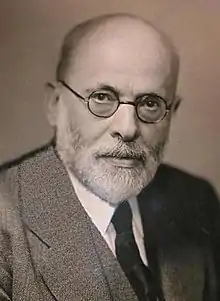

Gaetano Salvemini

Gaetano Salvemini (Italian pronunciation: [ɡaeˈtaːno salˈvɛːmini]; 8 September 1873 – 6 September 1957) was an Italian anti-fascist politician, historian and writer. Born in a family of modest means, he became an acclaimed historian both in Italy and abroad, in particular in the United States, after he was forced into exile by Mussolini's Fascist regime.

Gaetano Salvemini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 1 December 1919 – 7 April 1921 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 8, 1873 Molfetta, Apulia (Italy) |

| Died | September 6, 1957 (aged 83) Sorrento, Italy |

| Political party | Italian Socialist Party |

| Profession | Historian, writer |

Initially engaging with the Italian Socialist Party, he later adhered to an independent humanitarian socialism, while maintaining a commitment to radical political and social reform throughout his life. Salvemini offered significant leadership to political refugees in the United States. His prolific writings shaped the attitudes of U.S. policymakers during and after the Second World War. His transatlantic exile experience endowed him with new insights and a fresh perspective to explain the rise of fascism, while shaping the memory of the war and political life in Italy after 1945. He advocated a third way between Communists and Christian Democracy for post-war Italy.

Early life and career

Salvemini was born in the town of Molfetta, in Apulia in the poor south of Italy, in an extended family of farmers and fishermen of modest means. His father, Ilarione Salvemini, was a carabiniere and part-time teacher. He had been a radical republican who had fought as a Red Shirt following Giuseppe Garibaldi in his fight for Italian unification.[1][2] His mother Emanuela (née Turtur) was a socialist. His parents' political leanings as well as the poverty of the region, shaped his own political and social ideals throughout his life.[3]

He was admitted at the University of Florence, where he met mostly students of northern Italy and engaged with young socialists who introduced him to Marxism (which he would revise critically later), the ideas of Carlo Cattaneo and the Italian socialist Filippo Turati's journal Critica Sociale, as well as his first wife Maria Minervini.[2][4] After completing his studies in Florence in 1894, his historical studies on medieval Florence, the French Revolution and Giuseppe Mazzini established him as an acclaimed historian.[1]

In 1901, after years of teaching in secondary schools, he was appointed as a professor in medieval and modern history at the University of Messina. While in Messina, he lost his wife, five children and his sister in the devastating 1908 Messina earthquake before his eyes, while hiding under an architrave of a window; an experience that shaped his life. "I am a miserable wretch, without home or hearth, who has seen the happiness of eleven years destroyed in two minutes," he wrote.[5] He went on to teach history at the University of Pisa and in 1916 was appointed Professor of Modern History at the University of Florence.[1][2][4] Over the years, he aligned with Luigi Einaudi and gradually developed a pragmatic inquiry and inductive analysis, which he called concretismo – a combination of secular values from the enlightenment, liberalism and socialism – in contrast to more philosophical thinkers like Benedetto Croce and Antonio Gramsci.[2]

Engaging with socialism

.jpg.webp)

Salvemini became increasingly concerned with Italian politics and adhered to the Italian Socialist Party (Italian: Partito Socialista Italiano, PSI).[1] In 1910, he published an article in the socialist newspaper Avanti! entitled 'The minister of the underworld' (Il ministro della malavita), in which he attacked the power system and political machine of the liberal Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti who dominated Italian political life from the start of the 20th century.[6][7] Salvemini reproached Giolitti to exploit the backwardness of Southern Italy for short-term political goals, appeasing the landlords while engaging with corrupt political go-betweens with ties to the underworld.[8] According to Salvemini, Giolitti exploited "the miserable conditions of the Mezzogiorno in order to link the mass of southern deputies to himself".[9]

He opposed the costly military campaign in Libya during Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912). The war did not meet the real needs of the country in need of far-reaching economic and social reforms, according to Salvemini, but was a dangerous collusion between unrealistic nationalism and corporate interests.[4] In 1911, Salvemini left the PSI because of the "silence and indifference" on the war by the party[10] and founded the weekly political review L'Unità that would serve as the voice of militant democrats in Italy for the next decade. He criticised the government's imperial designs in Africa as chauvinist foolishness.[6]

However, he did favour Italy's entry in the First World War on the side of the Entente,[6] in order to achieve a greater political, economic and social stake in the nation by the masses, as well as national self-determination.[11] He became one of the leaders of the democratic interventionists with Leonida Bissolati.[2] Through the fight for democracy abroad, he believed, Italy would rediscover its own democratic roots.[3] Consistent with his interventionist position he joined as a volunteer in the first two years of the war.[4]

As a member of the PSI he fought for universal suffrage, for the moral and economic rebirth of Italy's Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy) and against corruption in politics. As a meriodanalist he criticised the PSI for its indifference for the problems of the South of Italy. While he abandoned the Socialist Party to adhere to an independent humanitarian socialism, he would maintain a commitment to radical reform throughout his life.[3] Elected on a list of ex-combatants, he served in the Italian Chamber of Deputies as an independent radical from 1919 to 1921 during the revolutionary period of the Biennio Rosso.[1][4] He supported the internationalist programme of self-determination of the U.S. president Woodrow Wilson, which envisioned a re-adjustment of the frontiers of Italy along clearly recognizable lines of nationality, in contrast to the irrendentist policy of Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino.[2]

Resisting fascism

In the immediate post-war period, Salvemini was initially silent about Italian Fascism,[1] but as a deputy he soon dissented from the political line of its parliamentary group and started a lively polemic against Benito Mussolini, who he had admired in the past as socialist leader, to the point that Mussolini even challenged him to a duel, which never took place.[4] Nevertheless, as late as 1922, he considered the fascist movement too small to be a serious political challenge.[3] Salvemini was more opposed to old-style politicians like Giolitti. "A return to Giolitti would be a moral disaster for the whole country," he wrote. "Mussolini was able to carry out his coup ... because everybody was disgusted by the Chamber."[12]

While in Paris he was surprised by Mussolini's March on Rome in October 1922, which initiated the Fascist take over of Italy.[2] In 1923, he held a series of lectures on Italian foreign policy in London, to the ire of the Fascist government and Florentine fascists. The walls of Florence were plastered with posters saying: "The monkey from Molfetta should not return to Italy". Instead, Salvemini not only returned home, but resumed his lectures at the University, regardless of the threat of fascist students.[4] He joined the opposition after the murder of the socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti on 10 June 1924, when it became clear that Mussolini wanted to establish a one-party dictatorship.[1]

He worked to maintain a strong network of contacts among anti-fascist intellectuals throughout Italy, while much of the Italian academic world bowed to the regime.[4] With his former students and followers Ernesto Rossi and Carlo Rosselli he founded the first clandestine anti-fascist newspaper Non mollare (Don't Give Up) in January 1925.[6][13] A half year later he was arrested and put on trial,[14] but was released on a technicality, although he was kept under surveillance.[15] Threats against his life were published in the Fascist press and his lawyer was beaten to death by Fascist blackshirts.[16] His name was on top of the list of the Fascist death squads during raids on 4 October 1925 in Florence.[17] However, Salvemini had fled to France in August 1925. He was dismissed from the University of Florence and his Italian citizenship was revoked in 1926.[6]

In exile Salvemini continued to actively organize resistance against Mussolini in France, England and finally in the United States. In 1927, he published The Fascist Dictatorship in Italy, a lucid and groundbreaking study of the rise of Fascism and Mussolini.[18] In Paris he was involved with the founding of Concentrazione antifascista in 1927 and Giustizia e Libertà with Carlo and Nello Rosselli in 1929.[1] Through these organizations, Italian exiles were helping the anti-fascists in Italy, spreading clandestine newspapers.[4] The movement intended to be a third alternative between fascism and communism, pursuing a free, democratic republic based on social justice.[3][19]

In the United States

Salvemini first toured the United States in January 1927, lecturing with a clear anti-fascist agenda.[20] His lectures were disturbed by fascist foes.[21][22] His forced exile nevertheless gave him a "sense of freedom, of spiritual independence." Rather than "exile" or "refugee," he preferred the term fuoruscito – an originally contemptuous label employed by Fascists, which was adopted as a symbol of honour by political exiles from Italy[17] –, "a man who has chosen to leave his country to continue a resistance which had become impossible at home".[3][23] He published The Fascist Dictatorship in Italy (1927), contradicting the widely held belief that Mussolini had saved Italy from Bolshevism.[24]

In 1934, Salvemini accepted to teach Italian civilization – a position created especially for him – at Harvard University, where he would remain until 1948.[4] Together with Roberto Bolaffio he founded a North American chapter of Giustizia e Libertà.[17] He wrote articles in important journals like Foreign Affairs and travelled around the country to warn American public opinion against the dangers of fascism.[1][25] Alarmed by the outbreak of the Second World War after Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, he and other Italian exiles founded the antifascist Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts.[3][25][26] Salvemini joined the Italian Emergency Rescue Committee (IERC), which raised money for Italian political refugees and worked to convince American authorities to admit them.[27]

He obtained US citizenship in 1940, believing that as an American citizen, he would have greater opportunity to influence U.S. policies toward Italy. In fact, government agencies like the State Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), solicited his advice on Fascism and Italian matters in general.[3] Notable writings of the American years include Under the Axe of Fascism (1936).[1][25][28] As an intellectual Salvemini left an undeniable mark on the study of Italian history at Harvard and other universities, changing their original focus on language, art and literature, to a critical and systematic study into modern Italy.[29]

The increasing prominence of Max Ascoli, Carlo Sforza and Alberto Tarchiani in the Mazzini Society consequently led to the progressive distancing of Gaetano Salvemini from active decision making. Salvemini's fear was that Roosevelt would give Churchill and his conservative agenda a free hand in post-war Italy that would benefit the monarchy and those that had collaborated with Mussolini.[30] After Mussolini's fall in July 1943, Salvemini became increasingly concerned that the Allies and Italian moderates favoured a conservative restoration in Italy. In order to provide an alternative, together with Harvard professor Giorgio La Piana, Salvemini authored What to do with Italy?, in which they sketched a plan for the reconstruction of Italy after the war along a republican and social-democratic programme.[1][3][31][32]

Back in Italy

Although a U.S. citizen, he returned to Italy in 1948 and was reinstated to his old post as Professor of Modern History at the University of Florence.[33] After 20 years of exile, he started his first speech at his old university with: "As we were saying in the last lecture".[34] As a left-leaning republican he was disappointed with the victory of the Christian Democratic party in the 1948 general election in Italy and the influence of the Catholic church in the country.[1] Salvemini hoped that the Action Party, a post-war political party that emerged from Giustizia e Libertà, could provide a third force, a socialist-republican coalition uniting reformist socialists and genuine democrats as an alternative for the Communists and the Christian Democrats. However, his hopes for a new Italy declined with the restoration of old attitudes and institutions with the start of the Cold War.[3]

In 1953, his last major historic study, Prelude to World War II, was published, about the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.[35][36] As a historian, he wrote mainly about recent and contemporary history, but was also noted for his studies of the medieval Italian commune. His The French Revolution: 1788–1792 is an outstanding explanation of the social, political and philosophical currents (and monarchical incompetence) that led to that cataclysm.[37]

Death and legacy

Salvemini spent the last period of his life in Sorrento, never ceasing to denounce the ancient Italian evils: inefficiency, the scandals, the lengthy justicial procedures that continued to favour the powerful. He lamented the failure of public schools that, according to him, were unable to form real critical conscience.[4] After a long illness, he died on September 6, 1957, at the age of 83.[38]

Salvemini was among the first and most effective opponents of Fascism. The political culture he embodied, made that, according to his biographer, Charles L. Killinger, "the Fascists were anti-Salvemini before he became anti-Fascist, and their efforts to silence him made his name synonymous with early Italian resistance to the new regime."[39] Although a prolific historian, he was not the kind of person to separate scholarship from political activity. Throughout his exile he actively organized resistance to Mussolini, assisting others in escaping Italy, while he played an important role in spurring both elite and public opinion in America against the Fascist regime.[40]

Giolitti's biographer, Alexander De Grand, describes his subject's foe as a "major historian, driven by an austere moralism" and as a "difficult man who attracted deep attachments and bitter enmity", who "constantly sought to turn his ideas into practical policy, yet he was a mediocre – no, terrible – politician," quoting Salvemini's fellow exile Max Ascoli who described him "as the greatest enemy of politics of all the men I have known".[41][42] Nevertheless, Salvemini was an imperative force who left a permanent mark on Italian politics and historiography. As a party activist, political commentator, and public officeholder, he championed social and political reform, and his name is tantamount to early Italian resistance to the new Fascist regime.[42] Salvemini said several times that he always tried to live by the principle: "Do what you have to do, come what may" (Fà quello che devi, avvenga quello che può).[4]

References

- Notes

- Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, p. 539

- Carnes, American National Biography, pp. 490-91

- Gaetano Salvemini (1873–1957): Historian, humanitarian socialist, and activist intellectual, by Mark Clark, in Transatlantic Perspectives (retrieved May 14, 2016)

- (in Italian) Biografia di Gaetano Salvemini, Istituto di studi storici Gaetano Salvemini (retrieved May 14, 2016)

- Pugliese, Carlo Rosselli, pp. 30-31

- Puzzo, Gaetano Salvemini, pp. 222-23

- Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, p. 314

- De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, p. 4

- Paoli, Broken bonds: Mafia and politics in Sicily

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 69

- Duggan, The Force of Destiny, p. 399

- Clark, Modern Italy, pp. 266-67

- Pugliese, Carlo Rosselli, p. 64

- Trial of Professors Is Exciting Italy, The New York Times, July 12, 1925

- Court In Florence Frees Professor, The New York Times, July 14, 1925

- Fascisti in Frenzy in Florence Riots, The New York Times, October 8, 1925

- Rose, The Dispossessed, pp. 135-37

- Puzzo, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 224

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 226

- Salvemini Arrives, Criticizes Fascism, The New York Times, January 6, 1927

- Police Drive Fascisti From Lecture By Foe, The New York Times, January 25, 1927

- 'Liar, Liar,' Halts Attack On Fascism, The New York Times, January 23, 1927

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 232

- Discrediting the Moral Pretensions of the Fascisti; Prof. Salvemini and Signor Prezzolini Maintain the Black Shirts Did Not Save Italy, The New York Times, June 12, 1927

- Puzzo, Gaetano Salvemini, pp. 226

- Rose, The Dispossessed, p. 140

- Rose, The Dispossessed, pp. 142-43

- The Case Against Mussolini and His Fascist Rule, The New York Times, May 17, 1936, Section Book Review, Page BR9

- Rose, The Dispossessed, p. 149

- Rose, The Dispossessed, p. 144

- Puzzo, Gaetano Salvemini, pp. 228-29

- Is Fascism Endemic?, The New York Times, September 12, 1943, Section Book Review, Page BR5

- Italian Professor Restored, The New York Times, November 8, 1948

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 313

- Puzzo, Gaetano Salvemini, pp. 230-32

- The War of Many Medals, The New York Times, January 10, 1954, Section Book Review, Page BR12

- Turbulent Years That Led to a Republic, The New York Times, July 24, 1955, Section Book Review, Page BR4

- Prof. Salvemini, Fought Fascism; Historian and Educator, 83, Dies, The New York Times, September 7, 1957, Page 14

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 173

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 3

- Killinger, Gaetano Salvemini, p. 274

- Grand on Killinger, 'Gaetano Salvemini: A Biography', H-Italy, March, 2003 (Retrieved 2 June 2016)

- Sources

- Camera dei deputati, Portale storico, Gaetano Salvemini

- Carnes, Mark C. (ed.) (2005). American National Biography: Supplement 2, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-522202-9

- Clark, Martin (1984/2014). Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-4058-2352-4

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2001). The hunchback's tailor: Giovanni Giolitti and liberal Italy from the challenge of mass politics to the rise of fascism, 1882-1922, Wesport/London: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-96874-X online edition

- Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-35367-4

- Killinger, Charles L. (2002). Gaetano Salvemini: a biography, Westport: Praeger, ISBN 978-0-275-96873-1 (Review)

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Broken bonds: Mafia and politics in Sicily, in: Godson, Roy (ed.) (2004). Menace to Society: Political-criminal Collaboration Around the World, New Brunswick/London: Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0-7658-0502-2

- Pugliese, Stanislao G. (1999). Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile, Cambridge (MA)/London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-00053-6

- Puzzo, Dante A. (April 1959). "Gaetano Salvemini: An Historiographical Essay". Journal of the History of Ideas. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 20, No. 2. 20 (2): 217–235. doi:10.2307/2707820. JSTOR 2707820.

- Rose, Peter Isaac (2005). The Dispossessed: An Anatomy of Exile, Amherst/Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 1-55849-465-0

- Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, New York: Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-81607-474-7