1948 Italian general election

General elections were held in Italy on Sunday 18 April 1948 to elect the first Parliament of the Italian Republic.[1] The elections were characterised by campaign financial and propaganda efforts conducted by the United States and Great Britain on behalf of the coalition led by the Christian Democracy party (Italian: Democrazia Cristiana, DC). The Soviet Union intervened by closely controlling the Communist Party of Italy, which led a coalition of its own.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

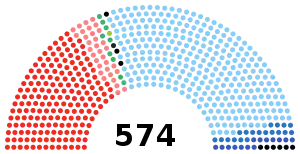

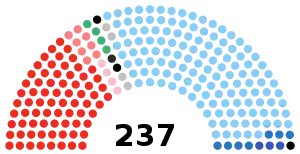

All 574 seats in the Chamber of Deputies 237 (out of 343) seats in the Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 92.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

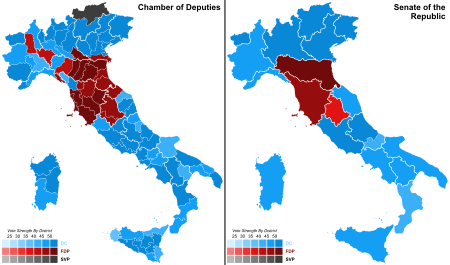

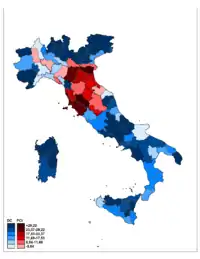

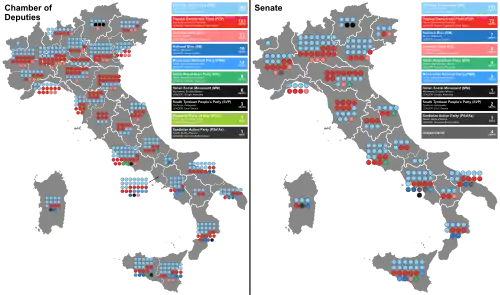

Results of the election in the Chamber and Senate. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in February 1948, the US became alarmed about Soviet intentions and feared that, if the leftist coalition were to win the elections, the communist left would draw Italy into the Soviet Union's sphere of influence. As the last month of the election campaign began, the Time magazine pronounced the possible leftist victory to be "the brink of catastrophe".[2]

On election day the parties on the left lost seats while those in the right gained. The winner by a comfortable margin by the DC coalition, defeating the left-wing coalition of the Popular Democratic Front (Italian: Fronte Democratico Popolare per la libertà, la pace, il lavoro, FDP) that comprised the Italian Communist Party (Italian: Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) and the Italian Socialist Party (Italian: Partito Socialista Italiano, PSI), on its part funded by the USSR.[3] The Christian Democrats went on to form a government without the Communists, who had been expelled from the government coalition in 1947 and remained frozen out.

Electoral system

The pure party-list proportional representation chosen two years before for the election of the Constituent Assembly, was definitely adopted for the Chamber of Deputies. Italian provinces were divided into 31 constituencies, each electing a group of candidates.[4] In each constituency, seats were divided between open lists using the largest remainder method with the Imperiali quota. Remaining votes and seats transferred to the national level, where special closed lists of national leaders received the last seats using the Hare quota.

For the Senate, 237 single-seat constituencies were created. The candidates needed a two-thirds majority to be elected, but only 15 aspiring senators were elected this way. All remaining votes and seats were grouped in party lists and regional constituencies, where the D'Hondt method was used: Inside the lists, candidates with the best percentages were elected.

This electoral system became standard in Italy, and was used until 1993.

Campaign

The elections remain unmatched in verbal aggression and fanaticism in Italy's period of democracy. According to the historian Gianni Corbi the 1948 election was "the most passionate, the most important, the longest, the dirtiest, and the most uncertain electoral campaign in Italian history".[5] The election was between two competing visions of the future of Italian society. On the right, a Roman Catholic, conservative and capitalist Italy, linked to the United States and Britain and represented by the governing Christian Democrats of De Gasperi. On the left a secular, revolutionary and socialist society, linked to the Soviet Union and represented by the Communist Party (PCI) and its Socialist ally.[5]

The Christian Democrat campaign pointed to the recent Communist coup in Czechoslovakia. It warned that in communist countries, "children send parents to jail", "children are owned by the state", and told voters that disaster would strike Italy if the communists were to take power.[6][7] Another slogan was "In the secrecy of the polling booth, God sees you - Stalin doesn't."[8]

The Popular Front campaign focused on living standards and avoided embarrassing questions of foreign policy, such as UN membership (vetoed by the USSR) and Yugoslav control of Trieste, or losing American financial and food aid. The PCI led the FDP coalition and had effectively marginalised the PSI, which thus eventually suffered because in the elections, in terms of parliamentary seats and political power;[9] The Socialists also had been hurt by the secession of a social-democratic faction led by Giuseppe Saragat, which contested the election with the concurrent list of Socialist Unity.

The PCI had difficulties in restraining its more militant members, who, in the period immediately after the war, had engaged in violent acts of reprisals. The areas affected by the violence (the so-called "Red Triangle" of Emilia, or parts of Liguria around Genoa and Savona, for instance) had previously seen episodes of brutality committed by the Fascists during Benito Mussolini's regime and the Italian Resistance during the Allied advance through Italy.

Superpower influence

The 1948 general election was greatly influenced by the Cold War that was underway with the Soviet Union against United States and Britain.[10] After his defeat in the election communist leader Togliatti stated on April 22 that, "The elections were not free....Brutal foreign intervention was used consisting of a threat to starve the country by withholding ERP aid if it voted for the Democratic Front... The menace to use the atom bomb against towns or regions" that voted pro-communist.[11] The US government's Voice of America radio began broadcasting anti-communist campaign pleased Italy on March 24, 1948.[12] The US Central Intelligence Agency, by its own admission, gave $1 million (equivalent to $10,640,000 in 2019) to what they referred to as "center parties"[13] and was accused of publishing forged letters in order to discredit the leaders of the Italian Communist Party.[14] The National Security Act of 1947, that made foreign covert operations possible, had been signed into law about six months earlier by the American President Harry S. Truman.

"We had bags of money that we delivered to selected politicians, to defray their political expenses, their campaign expenses, for posters, for pamphlets," according to CIA operative F. Mark Wyatt.[15]

In order to influence the election, the US agencies undertook a campaign of writing ten million letters, made numerous short-wave radio broadcasts and funded the publishing of books and articles, all of which warned the Italians of what was believed to be the consequences of a communist victory. Overall, the US funneled $10 million to $20 million (equivalent to $106,000,000 in 2019) into the country for specifically anti-PCI purposes. The CIA also made use of off-the-books sources of financing to interfere in the election: millions of dollars from the Economic Cooperation Administration affiliated with the Marshall Plan[16] and more than $10 million in captured Nazi money were steered to anti-communist propaganda.[17]

The Irish government, motivated by the country's devout Catholicism also inferred in the election by funneling the modern day equivalent of €2 million through the Irish Embassy to the Vatican who then distributed it to Catholic politicians. Joseph Walshe, the ambassador to the Vatican had privately suggested secretly funding Azione Cattolica.[18]

The CIA claims that the PCI was being funded by the Soviet Union.[19] Although the numbers are disputed, there is evidence of some financial aid, described as occasional and modest,[20] from the Kremlin.[21] PCI official Pietro Secchia and Stalin discussed financial support.[22] According to former CIA operative Mark Wyatt, "The Communist Party of Italy was funded...by black bags of money directly out of the Soviet compound in Rome; and the Italian services were aware of this. As the elections approached, the amounts grew, and the estimates [are] that $8 million to $10 million a month actually went into the coffers of communism. Not necessarily completely to the party: Mr. Di Vittorio and labor was powerful, and certainly a lot went to him"[14]

The Christian Democrats eventually won the 1948 election with 48% of the vote, and the FDP received 31%. The CIA's practice of influencing the political situation was repeated in every Italian election for at least the next 24 years.[15] A leftist coalition would not win a general election for the next 48 years, until 1996. That was partly because of Italians' traditional bent for conservatism and, even more importantly, the Cold War, with the US closely watching Italy, in their determination to maintain a vital NATO presence amidst the Mediterranean and retain the Yalta-agreed status quo of western Europe.[23]

Parties and leaders

Results

Christian Democracy won a sweeping victory, taking 48.5 percent of the vote and 305 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 131 seats in the Senate. With an absolute majority in both chambers, DC leader and premier Alcide De Gasperi could have formed an exclusively DC government. Instead, he formed a "centrist" coalition with Liberals, Republicans and Social Democrats. De Gasperi formed three ministries during the parliamentary term, the second one in 1950 after the defection of the Liberals, who hoped for more rightist politics, and the third one in 1951 after the defection of the Social-democrats, who hoped for more leftist politics.

Following a provision of the new republican constitution, all living democratic deputies elected during the 1924 general election and deposed by the National Fascist Party in 1926, automatically became members of the first republican Senate.

Chamber of Deputies

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy (DC) | 12,740,042 | 48.51 | 305 | +98 | |

| Popular Democratic Front (FDP) | 8,136,637 | 30.98 | 183 | −36 | |

| Socialist Unity (US) | 1,858,116 | 7.07 | 33 | New | |

| National Bloc (BN) | 1,003,727 | 3.82 | 19 | −52 | |

| Monarchist National Party (PNM) | 729,078 | 2.78 | 14 | −2 | |

| Italian Republican Party (PRI) | 651,875 | 2.48 | 9 | −14 | |

| Italian Social Movement (MSI) | 526,882 | 2.01 | 6 | New | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 124,243 | 0.47 | 3 | New | |

| Peasants' Party of Italy (PCdI) | 95,914 | 0.37 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Social Christian Party (PCS) | 72,854 | 0.28 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Sardinian Action Party (PSd'Az) | 61,928 | 0.24 | 1 | −1 | |

| Nationalist Movement for the Social Democracy | 56,096 | 0.21 | 0 | New | |

| Federalist Movements' Union | 52,655 | 0.20 | 0 | New | |

| Unionist People's Bloc | 35,899 | 0.14 | 0 | New | |

| Others | 118,512 | 0.44 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 591,283 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 26,855,741 | 100 | 574 | +18 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 29,117,270 | 92.23 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

Senate of the Republic

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy (DC) | 10,899,640 | 48.11 | 131 | ||

| Popular Democratic Front (FDP) | 6,969,122 | 30.76 | 72 | ||

| National Bloc (BN) | 1,222,419 | 5.40 | 7 | ||

| Socialist Unity (US) | 943,219 | 4.16 | 8 | ||

| US – PRI | 607,792 | 2.68 | 4 | ||

| Italian Republican Party (PRI) | 594,178 | 2.62 | 4 | ||

| Monarchist National Party (PNM) | 393,510 | 1.74 | 3 | ||

| Italian Social Movement (MSI) | 164,092 | 0.72 | 1 | ||

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 94,406 | 0.42 | 2 | ||

| Peasants' Party of Italy (PCdI) | 65,986 | 0.29 | 0 | ||

| Sardinian Action Party (PSd'Az) | 65,743 | 0.29 | 1 | ||

| Federalist Movements' Union | 42,880 | 0.19 | 0 | ||

| Nationalist Movement for the Social Democracy | 27,152 | 0.12 | 0 | ||

| Others | 22,108 | 0.10 | 0 | ||

| Independents | 544,039 | 2.40 | 4 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,185,629 | – | – | ||

| Total | 23,842,919 | 100 | 237 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 25,874,809 | 92.15 | – | ||

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

References

- Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe : a data handbook (1st ed.). Nomos. p. 1048. ISBN 9783832956097. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "ITALY: Fateful Day". Time. 22 March 1948. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Richard Drake, "The Soviet Dimension of Italian Communism", Cold War Studies.

- The number of seats for each constituency went from 1 for Aosta Valley to 36 for Milan.

- Ventresca, From Fascism to Democracy, p. 4

- "Show of Force", TIME Magazine, April 12, 1948

- "How to Hang On", TIME Magazine, April 19, 1948

- "Fertility vote galvanises Vatican", BBC News, 13 June 2005

- The Communist party gained more than the two-thirds of the seats won by the joint list. ("Number of MPs for each political group during the First Legislature", Italian Chamber of Deputies website.

- Brogi, Confronting America, pp. 101-110

- "Italian elections," Facts on File April 18–April 24, 1948, p. 125G.

- " Italy and Trieste," Facts on File March 21–March 27, 1948, p. 93E

- CIA memorandum to the Forty Committee (National Security Council), presented to the Select Committee on Intelligence, United States House of Representatives (the Pike Committee) during closed hearings held in 1975. The bulk of the committee's report that contained the memorandum was leaked to the press in February 1976 and first appeared in book form as CIA – The Pike Report (Nottingham, England, 1977). The memorandum appears on pp. 204-5 of this book.

- "CNN Cold War Episode 3: Marshall Plan. Interview with F. Mark Wyatt, former CIA operative in Italy during the election". CNN.com. 1998–1999. Archived from the original on 31 August 2001. Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- F. Mark Wyatt, 86, C.I.A. Officer, Is Dead, The New York Times, July 6, 2006

- Corke, Sarah-Jane (12 September 2007). US Covert Operations and Cold War Strategy: Truman, Secret Warfare and the CIA, 1945-53. Routledge. pp. 49–58. ISBN 9781134104130.

- Peter Dale Scott, Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 1 Nov. 2010, Volume 8 | Issue 44 | Number 2, "Operation Paper: The United States and Drugs in Thailand and Burma" 米国とタイ・ビルマの麻薬 citing Christopher Andrew, "For the President’s Eyes Only" (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 172

- https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/irish-state-secretly-intervened-in-italian-1948-general-election-1.2002970

- Brogi, Confronting America, p. 109

- Ventresca, From Fascism to Democracy, p. 269

- Callanan, Covert Action in the Cold War, pp. 41-45

- Pons, Silvio (2001), Stalin, Togliatti, and the Origins of the Cold War in Europe, Journal of Cold War Studies, Volume 3, Number 2, Spring 2001, pp. 3-27

- "N.A.T.O. Gladio, and the strategy of tension". Chapter from "NATO's Secret Armies. Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe", by daniele Ganser. October 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

Further reading

- Blum, William (2000). Killing Hope. Common Courage Press. ISBN 978-1-56751-053-9. Chapter 2 Italy 1947-1948: Free elections: Hollywood style

- Brogi, Alessandro (2011). Confronting America: The Cold War Between the United States and the Communists in France and Italy, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-3473-2

- Callanan, James (2010). Covert Action in the Cold War: US Policy, Intelligence and CIA Operations, London/New York: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-882-2

- Del Pero, Mario. "The United States and" psychological warfare" in Italy, 1948–1955." Journal of American History 87.4 (2001): 1304-1334. onlinr

- Luconi, Stefano. "Anticommunism, Americanization, and ethnic identity: Italian Americans and the 1948 parliamentary elections in Italy." Historian 62.2 (1999): 285–302. online

- Lundestad, Geir. "Empire by Invitation? The United States and Western Europe, 1945-1952." Journal of peace research 23.3 (1986): 263–277.

- Miller, James E. "Taking off the gloves: The United States and the Italian elections of 1948." Diplomatic History 7.1 (1983): 35–56. Online

- Mistry, Kaeten. "The case for political warfare: Strategy, organization and US involvement in the 1948 Italian election." Cold War History 6.3 (2006): 301–329.

- Pedaliu, Effie G.H. "The ‘British Way to Socialism’: British Intervention in the Italian Election of April 1948 and its Aftermath." in Pedaliu, Britain, Italy and the Origins of the Cold War (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2003) pp. 58-95.

- Pons, Silvio. "Stalin, Togliatti, and the origins of the cold war in Europe." Journal of Cold War Studies 3.2 (2001): 3-27. online

- Ventresca, Robert A. From Fascism to Democracy: Culture and Politics in the Italian Election of 1948, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004). ISBN 0-8020-8768-X

External links

- * Pedaliu, Effie GH. "The 18 April 1948 Italian election: seventy years on." LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog (2018). online

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1948 elections in Italy. |