Gambella National Park

Gambella National Park, or Gambela National Park, is a 4,575-square-kilometre (1,766 sq mi) national park in Ethiopia,[1] near the South Sudanese border. It is the nation's largest national park.[2] Gambella is located several hundred kilometers from Addis Ababa,[2] Gambella was established in 1974,[3] but is not fully protected and has not been effectively managed for much of its history.[4][5]

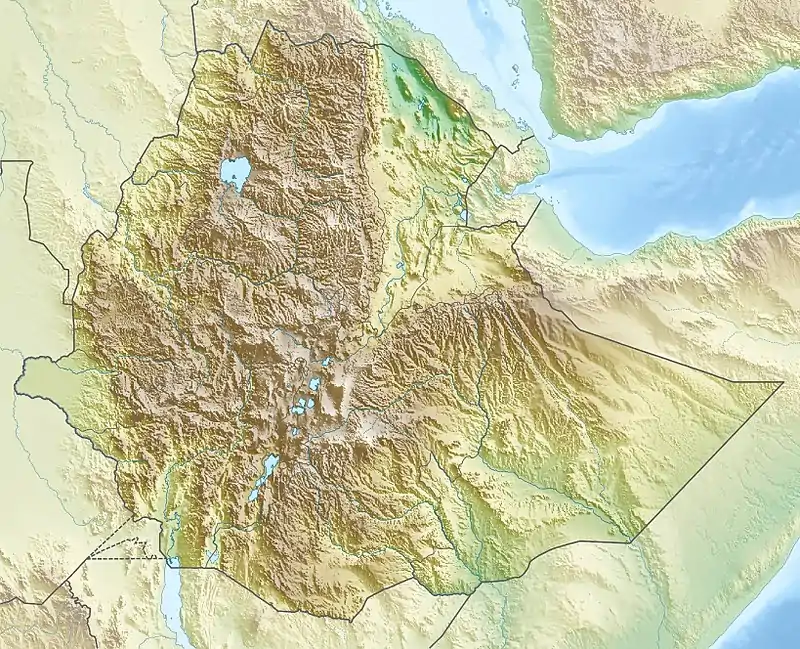

| Gambella National Park | |

|---|---|

Location in Ethiopia | |

| Location | Gambela Region, Ethiopia |

| Coordinates | 7°52′N 34°0′E |

| Area | 4,575 km2 (1,766 sq mi) |

| Established | 1974–1975 |

Fauna and flora

Gambella National Park has one of the highest concentrations of wildlife in Ethiopia.[6] 69 mammal species occur in the protected area including African elephant, African buffalo, White-eared kob bushpig, common warthog, giraffe, hippopotamus, kéwel, Nile lechwe, sable, tiang, topi, and waterbuck, cheetah, leopard, lion, mantled guereza, olive baboon, patas monkey, and spotted hyena.[2][7][8]

The park also hosts herds of Bohor reedbuck, bushbuck, Lelwel hartebeest, oribi, reedbuck, roan antelope, and white-eared kob.[2][7][8] The white-eared kob migration is Africa's second largest mammal migration.[9][10] In 2015, African Parks and the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority surveyed the park's giraffe population for the first time, and estimated there were between 100 and 120 giraffes. Gambella's giraffes were once thought to belong to the Nubian subspecies.[11][12][13]

327 bird species, including seasonal migrants, have been recorded, including the African skimmer, black-faced firefinch, Carmine bee-eater, cisticolas, crowned cranes, Egyptian plover, exclamatory paradise whydah, green bee-eater, pelicans, approximately 40 species of raptors, red-necked buzzard, red-throated bee-eater, storks, warblers, and vultures.[2][8]

Plant species along the Akobo and Baro rivers include: Acacia victoriae, Arundo donax, shenkorageda (Saccharum officinalis), and temba (Pennisetum petiolare). The invasive Eichhornia crassipes (water hyacinth) has also been reported.[7]

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit.[14]

Efforts to reduce poaching doubled the number of wild animals in the park between 2008 and 2012.[2]

History

Gambella was established during 1974–1975 to protect habitat and wildlife, especially the Nile lechwe and white-eared kob, two endangered antelope species.[7][8] Animal populations in the park have declined because of agriculture,[15] cotton farming, hunting, poaching, and the creation of refugee camps, especially following the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia and by displaced Sudanese.[8][10][16] Illegal deforestation by local communities has also led to conflict.[17]

In 2012, Bantayehu Wasyihun, head of the park's office, said infrastructure development was underway to make Gambella more accommodating to tourists.[2] The conservation organization African Parks and Addis Ababa University's Horn of Africa Research Centre worked with park officials to draft plans to improve Gambella's security and structure.[1][18]

See also

References

- "African Parks Annual Report: 2015" (PDF). African Parks. 2015. p. 80. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Ethiopia: Number of Wild Animals on Rise in Gambella National Park". African Conservation Foundation. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Zoomers, Annelies; Kaag, Mayke (13 February 2014). The Global Land Grab: Beyond the Hype. Zed Books. ISBN 9781780328973. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Rahmato, Dessalegn (2011). Land to Investors: Large-scale Land Transfers in Ethiopia. African Books Collective. p. 27. ISBN 9789994450404. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "... Gambella National Park has virtually ceased to exist as a conservation area...":

- Protected Areas of the World: Afrotropical. World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 1991. p. 100. ISBN 9782831700922. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Deininger, Klaus; Selod, Harris; Burns, Anthony (2012). The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector. World Bank Publications. p. 100. ISBN 9780821387580. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Plummer, Janelle (6 July 2012). Diagnosing Corruption in Ethiopia: Perceptions, Realities, and the Way Forward for Key Sectors. World Bank Publications. p. 297. ISBN 9780821395325. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- IUCN (1989). The IUCN Sahel Studies 1989. International Union for Conservation of Nature Regional Office for Eastern Africa. p. 105. ISBN 9782880329778. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Kebbede, Girma (4 October 2016). Environment and Society in Ethiopia. Taylor & Francis. p. 172. ISBN 9781315464282. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Briggs, Philip; Blatt, Brian (2009). Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 581. ISBN 9781841622842. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Wuerthner, George; Crist, Eileen; Butler, Tom (19 February 2015). Protecting the Wild: Parks and Wilderness, the Foundation for Conservation. Island Press. p. 173. ISBN 9781610915489. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- East, Rod (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. International Union for Conservation of Nature. p. 167. ISBN 9782831704777. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Morell, Virginia (25 June 2015). "Inside the Fight to Stop Giraffes' 'Silent Extinction'". National Geographic. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- "Petition to Lift the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) Under the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). International Fund for Animal Welfare. 19 April 2017. p. 15. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Shorrocks, Bryan (9 August 2016). The Giraffe: Biology, Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour. John Wiley & Sons. p. 317. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion West and Central Africa. Yaounde, Cameroon: IUCN.

- Negm, Abdelazim M. (2017). The Nile River. Springer. p. 324. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Woube, Mengistu (2005). Effects of Resettlement Schemes on the Biophysical and Human Environments: The Case of the Gambela Region, Ethiopia. Universal-Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 9781581124835. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir (15 June 2015). "The lesser known story of India's role in Ethiopian land grabs". The Ecologist. ISSN 0012-9631. OCLC 263593196. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Briggs, Philip (22 October 2015). Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 605. ISBN 9781841629223. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

Further reading

- Carbon Stock Potential of Gambella National Park. Lap Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH KG. 2013. ISBN 9783659466427.