Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (Amharic: አዲስ አበባ, Addis Abäba IPA: [adˈdis ˈabəba] (![]() listen), "new flower"), also known as Finfinne[4] (Oromo: Finfinne "natural spring"), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia.[5] According to the 2007 census, the city has a population of 2,739,551 inhabitants.[2] As a chartered city, Addis Ababa also serves as the capital city of the Oromia Region.[6] It is where the African Union is headquartered and where its predecessor the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was based. It also hosts the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), as well as various other continental and international organisations. Addis Ababa is therefore often referred to as "the political capital of Africa" for its historical, diplomatic and political significance for the continent.[7] The city lies a few miles west of the East African Rift which splits Ethiopia into two, between the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate.[8] The city is surrounded by the Special Zone of Oromia and populated by people from different regions of Ethiopia. It is home to Addis Ababa University.

listen), "new flower"), also known as Finfinne[4] (Oromo: Finfinne "natural spring"), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia.[5] According to the 2007 census, the city has a population of 2,739,551 inhabitants.[2] As a chartered city, Addis Ababa also serves as the capital city of the Oromia Region.[6] It is where the African Union is headquartered and where its predecessor the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was based. It also hosts the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), as well as various other continental and international organisations. Addis Ababa is therefore often referred to as "the political capital of Africa" for its historical, diplomatic and political significance for the continent.[7] The city lies a few miles west of the East African Rift which splits Ethiopia into two, between the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate.[8] The city is surrounded by the Special Zone of Oromia and populated by people from different regions of Ethiopia. It is home to Addis Ababa University.

Addis Ababa

| |

|---|---|

From top: Addis Ababa City Skyline, Addis Ababa Light Rail Vehicle, Friendship Square, Night view of Addis Ababa Light Rail transport, Addis Ababa University, Holy Trinity Cathedral, St. George's Cathedral | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nicknames: City of Humans, Sheger | |

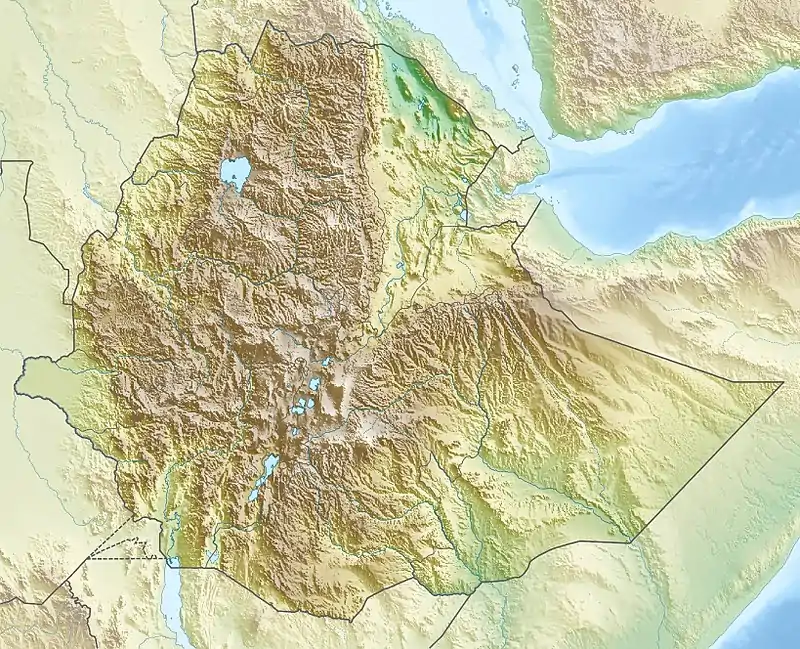

Addis Ababa Location in Ethiopia  Addis Ababa Addis Ababa (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E | |

| Country | Ethiopia |

| Chartered | 1886 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Adanech Abebe |

| Area | |

| • Chartered city | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| • Land | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Elevation | 2,355 m (7,726 ft) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • Chartered city | 3,384,569 |

| • Density | 5,165.1/km2 (13,378/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,384,569 |

| • Metro | 4,567,857 |

| [2] | |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (East Africa Time) |

| Area code(s) | (+251) 11 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.697[3] medium · 1st |

| Website | Official website |

History

Prior to the establishment of present-day Addis Ababa the location was called Finfinne in the Oromo language, which attests the presence of hot springs. The area was inhabited by various Oromo clans.[9] In 1886 the city was chosen by Menelik II as the capital of his kingdom of Shoa and was renamed to Addis Ababa.[10] The city's immediate predecessor as capital of Ethiopia, Entoto, was situated on a high tableland and was found to be unsatisfactory because of its cold climate and an acute shortage of firewood.[11] Entoto is one of a handful of sites put forward as a possible location for a medieval imperial capital known as Barara. This permanent fortified city was established during the early-to-mid 15th century, and it served as the main residence of several successive emperors up to the early 16th-century reign of Lebna Dengel.[12] For instance, Baeda Maryam I (1468-1478) set up royal court in nearby Gurage country from his initial place of reign and birthplace Debre Berhan, which would have encompassed this general region. [13] The city was depicted standing between Mounts Zikwala and Menegasha on a map drawn by the Italian cartographer Fra Mauro in around 1450, and it was razed and plundered by Ahmed Gragn while the imperial army was trapped on the south of the Awash River in 1529, an event witnessed and documented two years later by the Yemeni writer Arab-Faqih. The suggestion that Barara was located on Mount Entoto is supported by the very recent discovery of a large medieval town overlooking Addis Ababa located between rock-hewn Washa Mikael and the more modern church of Entoto Maryam, founded in the late 19th century by Emperor Menelik. Dubbed the Pentagon, the 30-hectare site incorporates a castle with 12 towers, along with 520 meters of stone walls measuring up to 5-meter high.[14]

The site of Addis Ababa was chosen by Empress Taytu Betul and the city was founded in 1886 by Emperor Menelik II.[15] Menelik, as initially a King of the Shewa province, had found Mount Entoto a useful base for military operations in the south of his realm, and in 1879 he visited the reputed ruins of a medieval town and an unfinished rock church that showed proof of the medieval empire's capital in the area before the campaigns of Ahmad ibn Ibrihim. His interest in the area grew when his wife Taytu began work on a church on Mount Entoto, and Menelik endowed a second church in the area.[12][14]

However, the immediate area of Entoto did not encourage the founding of a town for lack of firewood and water, so settlement actually began in the valley south of the mountain in 1886. Initially, Taytu built a house for herself near the "Filwoha" hot mineral springs, where she and members of the Showan Royal Court liked to take mineral baths. Other nobility and their staff and households settled in the vicinity, and Menelik expanded his wife's house to become the Imperial Palace which remains the seat of government in Addis Ababa today. The name changed to Addis Ababa and became Ethiopia's capital when Menelik II became Emperor of Ethiopia. The town grew by leaps and bounds. One of Emperor Menelik's contributions that are still visible today is the planting of numerous eucalyptus trees along the city streets.[16]

Following all the major engagements of their invasion, Italian troops from the colony of Eritrea entered Addis Ababa on 5 May 1936. Along with Dire Dawa, the city had been spared the aerial bombardment (including the use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas) practised elsewhere in Ethiopia. This also allowed its railway to Djibouti to remain intact. After the occupation, the city served as the Duke of Aosta's capital for unified Italian East Africa until 1941, when it was abandoned in favour of Amba Alagi and other redoubts during the Second World War's East African Campaign. The city was liberated by Major Orde Wingate and negus Haile Selassie for Ethiopian Gideon Force and Ethiopian resistance in time to permit Emperor Haile Selassie's return on 5 May 1941, five years to the day after he had left. Following reconstruction, Haile Selassie helped form the Organisation of African Unity in 1963 and invited the new organisation to keep its headquarters in Addis Ababa. The OAU was dissolved in 2002 and replaced by the African Union (AU), which is also headquartered in the city. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa also has its headquarters in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa was also the site of the Council of the Oriental Orthodox Churches in 1965.

Ethiopia has often been called the original home of mankind because of various humanoid fossil discoveries like the Australopithecine Lucy.[17] Northeastern Africa, and the Afar region in particular, was the central focus of these claims until recent DNA evidence suggested origins in south central Ethiopian regions like present-day Addis Ababa.[18][19] After analysing the DNA of almost 1,000 people around the world, geneticists and other scientists claimed people spread from what is now Addis Ababa 100,000 years ago.[20][21] The research indicated that genetic diversity decreases steadily the farther one's ancestors travelled from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.[22][23]

Geography

.png.webp)

Addis Ababa lies at an elevation of 2,355 metres (7,726 ft) and is a grassland biome, located at 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E.[24] The city lies at the foot of Mount Entoto and forms part of the watershed for the Awash. From its lowest point, around Bole International Airport, at 2,326 metres (7,631 ft) above sea level in the southern periphery, Addis Ababa rises to over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) in the Entoto Mountains to the north.

Subdivision

The city is divided into 10 boroughs, called subcities (Amharic: ክፍለ ከተማ, kifle ketema), and 99 wards (Amharic: ቀበሌ, kebele).[25][26] The 10 subcities are:

| Nr | Subcity | Area (km2) | Population | Density | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Addis Ketema[27] | 7.41 |

271,644 |

36,659.1 |

|

2 |

Akaky Kaliti[28] | 118.08 |

195,273 |

1,653.7 |

|

3 |

Arada[29] | 9.91 |

225,999 |

23,000 |

|

4 |

Bole[30] | 122.08 |

328,900 |

2,694.1 |

|

5 |

Gullele[31] | 30.18 |

284,865 |

9,438.9 |

|

6 |

Kirkos[32] | 14.62 |

235,441 |

16,104 |

|

7 |

Kolfe Keranio[33] | 61.25 |

546,219 |

7,448.5 |

|

8 |

Lideta[34] | 9.18 |

214,769 |

23,000 |

|

9 |

Nifas Silk-Lafto[35] | 68.30 |

335,740 |

4,915.7 |

|

10 |

Yeka[36] | 85.46 |

337,575 |

3950.1 |

Climate

| Addis Ababa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Addis Ababa has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen: Cwb) with precipitation varying considerably by the month.[38] The city has a complex mix of alpine climate zones, with temperature differences of up to 10 °C (18 °F), depending on elevation and prevailing wind patterns. The high elevation moderates temperatures year-round, and the city's position near the equator means that temperatures are very constant from month to month. As such the climate would be maritime if its elevation was not taken into account, as no month is above 22 °C (72 °F) in mean temperatures.

Mid-November to January is a season for occasional rain. The highland climate regions are characterised by dry winters, and this is the dry season in Addis Ababa. During this season the daily maximum temperatures are usually not more than 23 °C (73 °F), and the night-time minimum temperatures can drop to freezing. The short rainy season is from February to May. During this period, the difference between the daytime maximum temperatures and the night-time minimum temperatures is not as great as during other times of the year, with minimum temperatures in the range of 10–15 °C (50–59 °F). At this time of the year, the city experiences warm temperatures and a pleasant rainfall. The long wet season is from June to mid-September; it is the major winter season of the country. This period coincides with summer, but the temperatures are much lower than at other times of year because of the frequent rain and hail and the abundance of cloud cover and fewer hours of sunshine. This time of the year is characterised by dark, chilly and wet days and nights. The autumn which follows is a transitional period between the wet and dry seasons.

The highest temperature on record was 30.6 °C (87.1 °F) 26 February 2019, while the lowest temperature on record was 0 °C (32 °F) recorded on multiple occasions.[39]

| Climate data for Addis Ababa (1981–2010, extremes 1898–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.8 (83.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (74) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.0 (60.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

11 (52) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

7 (45) |

9 (49) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 13 (0.5) |

30 (1.2) |

58 (2.3) |

82 (3.2) |

84 (3.3) |

138 (5.4) |

280 (11.0) |

290 (11.4) |

149 (5.9) |

27 (1.1) |

7 (0.3) |

7 (0.3) |

1,165 (45.9) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 27 | 26 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 132 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 52 | 51 | 53 | 59 | 55 | 68 | 78 | 80 | 75 | 57 | 53 | 53 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 266.6 | 206.2 | 241.8 | 210.0 | 238.7 | 174.0 | 111.6 | 133.3 | 162.0 | 248.0 | 267.0 | 288.3 | 2,547.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.6 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation (average high and low, and rainfall)[40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (mean temperatures 1961–1990, humidity 1951–1990, and sun 1985–1998)[41] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[39] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

As of the latest 2007 population census conducted by the Ethiopian national statistics authorities, Addis Ababa has a total population of 2,739,551 urban and rural inhabitants. For the capital city 662,728 households were counted living in 628,984 housing units, which results in an average of 5.3 persons to a household. Although all Ethiopian ethnic groups are represented in Addis Ababa because it is the capital of the country, the largest groups include the Amhara (47.0%), Oromo (19.5%), Gurage (16.3%), Tigrayan (6.18%), Silt'e (2.94%), and Gamo (1.68%). Languages spoken as mother tongues include Amharic (71.0%), Afaan Oromo (10.7%), Gurage (8.37%), Tigrinya (3.60%), Silt'e (1.82%) and Gamo (1.03%). The religion with the most believers in Addis Ababa is Ethiopian Orthodox with 74.7% of the population, while 16.2% are Muslim, 7.77% Protestant, and 0.48% Catholic.[2]

In the previous census, conducted in 1994, the city's population was reported to be 2,112,737, of whom 1,023,452 were men and 1,089,285 were women. At that time not all of the population were urban inhabitants; only 2,084,588 or 98.7% were. For the entire administrative council there were 404,783 households in 376,568 housing units with an average of 5.2 persons per household. The major ethnic groups included the Amhara (48.3%), Oromo (30.2%), Gurage (13.5%; 2.3% Sebat Bet, and 0.8% Sodo), Tigrayan 7.64%, Silt'e 3.98%, and foreigners from Eritrea 1.33%. Languages spoken included Amharic (51.6%), Afaan Oromo (32.0%), Gurage (6.54%), Tigrinya (5.41%), and Silt'e 2.29%. In 1994 the predominant religion was also Ethiopian Orthodox with 82.0% of the population, while 12.7% were Muslim, 3.87% Protestant, and 0.78% Catholic.[43]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1,412,575 | — |

| 1994 | 2,112,737 | +49.6% |

| 2007 | 2,739,551 | +29.7% |

| 2015 | 3,273,000 | +19.5% |

| source:[44] | ||

Languages

Standard of living

According to the 2007 national census, 98.64% of the housing units of Addis Ababa had access to safe drinking water, while 14.9% had flush toilets, 70.7% pit toilets (both ventilated and unventilated), and 14.3% had no toilet facilities.[45] In 2014, there were 63 public toilets in the city, with plans to build more.[46] Values for other reported common indicators of the standard of living for Addis Ababa as of 2005 include the following: 0.1% of the inhabitants fall into the lowest wealth quintile; adult literacy for men is 93.6% and for women 79.95%, the highest in the nation for both sexes; and the civic infant mortality rate is 45 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, which is less than the nationwide average of 77; at least half of these deaths occurred in the infants' first month of life.[47]

The City is partially powered by water at the Koka Reservoir.

Economy

The economic activities in Addis Ababa are diverse. According to official statistics from the federal government, some 119,197 people in the city are engaged in trade and commerce; 113,977 in manufacturing and industry; 80,391 Homemakers of different variety; 71,186 in civil administration; 50,538 in transport and communication; 42,514 in education, health and social services; 32,685 in hotel and catering services; and 16,602 in agriculture. In addition to the residents of rural parts of Addis Ababa, the city dwellers also participate in animal husbandry and cultivation of gardens. 677 hectares (1,670 acres) of land is irrigated annually, on which 129,880 quintals of vegetables are cultivated. It is a relatively clean and safe city, with the most common crimes being pickpocketing, scams and minor burglary.[48] The city has recently been in a construction boom with tall buildings rising in many places. Various luxury services have also become available and the construction of shopping malls has recently increased. According to Tia Goldenberg of IOL, area spa professionals said that some people have labelled the city, "the spa capital of Africa."[49]

Ethiopian Airlines has its headquarters on the grounds of Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa.[50]

Tourism

Tourism is a growing industry within Addis Ababa and Ethiopia as a whole. The country has seen a 10% increase in tourism over the last decade, subsequently bringing an influx of tourists to Addis Ababa. In 2015, the European Council on Tourism and Trade named Ethiopia the Number One tourist spot in the world.[51]

Zoo

Addis Ababa Zoo kept 15 lions in 2011. Their hair samples were used in a genetic analysis, which revealed that they were genetically diverse. It was therefore proposed to include them in a captive breeding programme.[52]

Law and government

Government

Pursuant to the Ethiopian Constitution of 1995, the city of Addis Ababa is one of the two federal cities that are accountable to the Federal Government of Ethiopia. The other city with the same status is Dire Dawa in the east of the country and both are federal cities. Earlier, following the establishment of the federal structure in 1991 under the Transitional Charter of Ethiopia, the City Government of Addis Ababa was one of the then new 14 regional governments. However, that structure was changed by the federal constitution in 1995 and as a result, Addis Ababa does not have statehood status.

The administration of Addis Ababa city consists of the Mayor, who leads the executive branch, and the City Council, which enacts city regulations. However, as part of the Federal Government, the federal legislature enacts laws that are binding in Addis Ababa. Members of the City Council are directly elected by the residents of the city and the Council, in turn, elects the Mayor among its members. The term of office for elected officials is five years. However, the Federal Government, when it deems necessary, can dissolve the City Council and the entire administration and replace it by a temporary administration until elections take place next. Residents of Addis Ababa are represented in the federal legislature, the House of Peoples' Representatives. However, the city is not represented in the House of Federation, which is the federal upper house constituted by the representatives of the member states. The executive branch under the Mayor comprises the City Manager and various branches of civil service offices.

The Mayor of Addis Ababa is Engineer Takele Uma Benti from the Oromo Democratic Party, ODP formerly Oromo People Democratic Organisation (OPDO), which is the member of the ruling coalition Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Engineer Takele Uma took office in 2018. His predecessor, Mr. Dirribaa Kumaa and Kumaa Dammaqsaa (also both from the ODP), were the city's mayor respectively before Takele. Before that, the Federal Government appointed Mr. Berhane Deressa to lead the temporary caretaker administration that served from 9 May 2006 to 30 October 2008 following the 2005 election crisis. In the 2005 national election, the ruling EPRDF party suffered a major defeat in Addis Ababa. However, the opposition who won in Addis Ababa did not take part in the government both on the regional and federal level. This situation forced the EPRDF-led Federal Government to assign a temporary administration until a new election was carried out. As a result, Mr. Berhane Deressa, an independent citizen, was appointed.

Some of the notable past mayors of Addis Ababa are Arkebe Oqubay (2003–06), Zewde Teklu (1985–89), Alemu Abebe (1977–85) and Zewde Gebrehiwot (1960–69).

Crime

Addis Ababa is considered to be extremely safe in comparison to the other cities in the region.[53] On a crime index, Addis Ababa scores a 44.28, putting it at a crime level of moderate. Pickpocketing and petty unarmed thefts are more common within the city. Corruption and bribery are extremely common crimes in Addis Ababa. Violent crimes are very unlikely to happen in the city.[54]

Places of worship

.jpeg.webp)

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Christian churches and temples : Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (Lutheran World Federation), Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church, Ethiopian Catholic Archeparchy of Addis Abeba (Catholic Church), Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers' Church[55] and also Muslim mosques.

Architecture

A financial district is under construction in Addis Ababa.[56]

Mayor Kuma Demeksa embarked on a quest to improve investment for the buildings in the city. Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union.[57]

Notable taller architecture in Addis Ababa includes the CBE headquarters, NIB international bank, Zemen bank, Hibret bank, Huda Tower, Nani Tower, Bank Misr Building, as well as the approved Angola World Trade Center Tower, Abyssinia Bank Tower, Mexico Square Tower, and the $200m AU Conference Center and Office Complex.[58]

Notable buildings include St George's Cathedral (founded in 1896 and also home to a museum), Holy Trinity Cathedral (once the largest Ethiopian Orthodox Cathedral and the location of Sylvia Pankhurst's tomb) as well as the burial place of Emperor Haile Selassie and the Imperial family, and those who fought the Italian invasion during World War II.

In the Merkato district, which is the largest open market in Africa, is the Grand Anwar Mosque, the biggest mosque in Ethiopia built during the Italian occupation. A few meters to the southwest of the Anwar Mosque is the Raguel Church built after the liberation by Empress Menen. The proximity of the mosque and the church has symbolised the long peaceful relations between Christianity and Islam in Ethiopia. The Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Holy Family is also in the Merkato district. Near Bole International Airport is the new Medhane Alem (Savior of the World) Orthodox Cathedral, which is the second largest in Africa.

The Entoto Mountains start among the northern suburbs. Suburbs of the city include Shiro Meda and Entoto in the north, Urael and Bole (home to Bole International Airport) in the east, Nifas Silk in the south-east, Mekanisa in the south, and Keraniyo and Kolfe in the west. Kolfe was mentioned in Nelson Mandela's Autobiography "A Long Walk to Freedom", as the place he got military training.

Addis Ababa has a distinct architectural style. Unlike many African cities, Addis Ababa was not built as a colonial settlement. This means that the city has not a European style of architecture. This changed with the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936. The Piazza district in the city center is the most evident indicator of Italian influence. The buildings are very much Italian in style and there are many Italian restaurants, as well as small cafes, and European-style shopping centers.[59]

Parks include the Africa Park, which is situated along Menelik II Avenue.

Other features of the city include the large Mercato market, the Jan Meda racecourse, Bihere Tsige Recreation Centre and a railway line to Djibouti.

The city is home to the Ethiopian National Library, the Ethiopian Ethnological Museum (and former Guenete Leul Palace), the Addis Ababa Museum, the Ethiopian Natural History Museum, the Ethiopian Railway Museum and National Postal Museum.

There is also Menelik's old Imperial palace which remains the official seat of government, and the National Palace formerly known as the Jubilee Palace (built to mark Emperor Haile Selassie's Silver Jubilee in 1955) which is the residence of the President of Ethiopia. Jubilee Palace was also modelled after Buckingham Palace in the United Kingdom. Africa Hall is located across Menelik II avenue from this Palace and is where the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa is headquartered as well as most UN offices in Ethiopia. It is also the site of the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which eventually became the African Union (AU). The African Union is now housed in a new headquarters built on the site of the demolished Akaki Prison, on land donated by Ethiopia for this purpose in the south western part of the city. The Hager Fikir Theatre, the oldest theatre in Ethiopia, is located at the Piazza district. Near Holy Trinity Cathedral is the art deco Parliament building, built during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, with its clock tower. It continues to serve as the seat of Parliament today. Across from the Parliament is the Shengo Hall, built by the Derg regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam as its new parliament hall. The Shengo Hall was the world's largest pre-fabricated building, which was constructed in Finland before being assembled in Addis Ababa. It is used for large meetings and conventions. Itegue Taitu Hotel, built in 1898 (Ethiopian Calendar) in the middle of the city (Piazza), was the first hotel in Ethiopia.

Meskel Square is one of the noted squares in the city and is the site for the annual Meskel at the end of September annually when thousands gather in celebration.

The fossilised skeleton, and a plaster replica of the early hominid Lucy (known in Ethiopia as Dinkinesh) is preserved at the National Museum of Ethiopia.

Sport

Sport facilities include Addis Ababa and Nyala Stadiums. The 2008 African Championships in Athletics were held in Addis Ababa.

Development

The city hosts the We Are the Future center, a child care center that provides children with a higher standard of living. The center is managed under the direction of the mayor's office, and the international NGO Glocal Forum serves as the fundraiser and program planner and coordinator for the WAF child center in each city. Each WAF city is linked to several peer cities and public and private partners to create a unique international coalition.

Launched in 2004, the program is the result of a strategic partnership between the Glocal Forum, the Quincy Jones Listen Up Foundation and Mr. Hani Masri, with the support of the World Bank, UN agencies and major companies.

Gallery

Arat Kilo monument

Arat Kilo monument Addis Ababa Sheger Park

Addis Ababa Sheger Park Unity Park Addis Ababa

Unity Park Addis Ababa Commercial Bank of Ethiopia

Commercial Bank of Ethiopia

Hager Fikir Theatre (April 2006)

Hager Fikir Theatre (April 2006) Ethiopian Radio and Television station

Ethiopian Radio and Television station Headquarters of the Ethiopian Federal Police

Headquarters of the Ethiopian Federal Police Light rail overpass at Mexico Square, Addis Ababa

Light rail overpass at Mexico Square, Addis Ababa

Education

Addis Ababa University was founded in 1950 and was originally named "University College of Addis Ababa", then renamed in 1962 for the former Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I who had donated his Genete Leul Palace to be the university's main campus in the previous year. It is the home of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies and the Ethnological Museum. The city also has numerous public universities and private colleges including Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Ethiopian Civil Service University, Admas University College, St. Mary's University, Unity University, Kotebe Metropolitan University and Rift Valley University.

Transport

Public transport is through public buses from three different companies (Anbessa City Bus Service Enterprise, Sheger, Alliance), Light Rail or blue and white taxis. The taxis are usually minibuses that can seat at most twelve people, which follow somewhat pre-defined routes. The minibus taxis are typically operated by two people, the driver and a weyala who collects fares and calls out the taxi's destination. Sedan taxis work like normal taxis, and are driven to the desired destination on demand. In recent years, new taxi companies have appeared, which uses other designs, including one large company using yellow sedan taxis.

Road

The construction of the Addis Ababa Ring Road was initiated in 1998 to implement the city master plan and enhance peripheral development. The Ring Road was divided into three major phases that connect all the five main gates in and out of Addis Ababa with all other regions (Jimma, Bishoftu, Dessie, Gojjam and Ambo). For this project, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) was the partner of Addis Ababa City Roads Authority (AACRA).[60] The Ring Road has greatly helped to decongest and alleviate city traffic.

Intercity bus service is provided by the Lion City Bus Services.

Air

The city is served by Addis Ababa Bole International Airport, where a new terminal opened in 2003. The old Lideta Airport in the western "Old Airport" district is used mostly by small craft and military planes and helicopters.

Railway

Addis Ababa originally had a railway connection with Djibouti City, with a picturesque French style railway station, but this route has been abandoned. The new Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway started operation in September 2016, running parallel to the route of the original railway line.

Light rail

Addis Ababa opened its light rail system to the public on 20 September 2015. The system is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Ethiopian Railway Corporation reached a funding agreement worth millions of dollars with the Export and Import Bank of China in September 2010 and the light rail project was completed in January 2015. The route is a 34.25-kilometre (21.28 mi) network with two lines; the operational line running from the center to the south of the city. Upon completion, the east–west line will run from Ayat to the Torhailoch ring-road, and from Menelik Square to Merkato Bus Station, Meskel Square and Akaki.[61]

Twin towns – sister cities

Notable people

- Ephraim Isaac: Scholar of Ancient Semitic Studies[64]

- Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi: richest person in Ethiopia (worth $8.1 billion)[65]

- Haile Gebrselassie: Ethiopian long distance runner

- Kenenisa Bekele: Ethiopian long distance runner

- Tedros Adhanom: Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO)

- Saladin Said: Ethiopian soccer player

- Mulatu Astatke: Ethiopian Jazz musician

- Mahmoud Ahmed: Ethiopian singer

- Teddy Afro: Ethiopian singer

- Bethlehem Tilahun Alemu: Founder of Sole Rebels[66]

- Eténèsh Wassié: Ethiopian azmari

- Ruth Negga: Actress[67]

See also

References

- "2011 National Statistics". Csa.gov.et. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "Census 2007 Tables: Addis Abeba" Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.5, 3.1, 3.2 and 3.4. For Silt'e, the statistics of reported Shitagne speakers were used, on the assumption that this was a typographical error.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- spelled Finfine in official web site of Oromia Supreme Court (http://www.oromiyaa.gov.et/web/supreme-court)

- "Addis Ababa | national capital, Ethiopia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Oromia Regional State". Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "United Nations Economic Commission for Africa". UNECA. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Gizaw, Berhanu. "The origin of high bicarbonate and fluoride concentrations in waters of the Main Ethiopian Rift Valley, East African Rift system." Journal of African Earth Sciences 22.4 (1996): 391–402.

- Endalew Djirata Fayisa. "Foundation of Addis Ababa and the Emergence of Safars".

- "Addis Ababa".

- "Addis Ababa national capital, Ethiopia".

- Philip Briggs. Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides (2015) pp. 49–50

- Paul B. Henze . Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (2000)

- Philip Briggs. Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides (2015) pp. 131–132

- Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 6

- Pankhurst, p. 195

- African tribe from Ethiopia populated rest of the world.

- "Humans Moved From Africa Across Globe, DNA Study Says". Bloomberg. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010.

- "DNA Links Humanity To One Common Origin: Africa". Archived from the original on 14 September 2009.

- "Around the world from Addis Ababa". Startribune.com. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "New Study Proves Theory of Human Recent African Origin". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008.

- Brown, David (22 February 2008). "Genetic Mutations Offer Insights on Human Diversity". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "DNA studies trace migration from Ethiopia". Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "NGA: Country Files". Earth-info.nga.mil. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Addis Ababa city website (site map, see the list in "Sub Cities" section)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Article at unhabitat.org (map of Addis Ababa, page 9)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Addis Ketema page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Akaky Kaliti page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Arada page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Bole page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Gullele page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Kirkos page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Kolfe Keranio page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Lideta page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Nifas Silk-Lafto page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Yeka page (Addis Ababa website)". Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "NMA of Ethiopia". National Meteorological Agency of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- "Climate: Addis Abeba (altitude: 2350m) – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Station Addis Abeba" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "World Weather Information Service – Addis Ababa". World Meteorological Organisation. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Klimatafel von Addis Abeba (Adis Ababa) / Äthiopien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Central Statistical Agency. 2010. Population and Housing Census 2007 Report, National. [ONLINE] Available at: http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/3583/download/50086 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. [Accessed 13 December 2016].

- "The 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Addis Ababa", Tables 2.1, 2.2, 2.8, 2.13A Archived 15 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Addis Ababa population statistics

- "Census 2007 Tables: Addis Abeba", Tables, 8.7, 8.8

- Smith, David (28 August 2014). "Ethiopians' plight: 'The toilets are unhealthy, but we don't have a choice'". Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2016 – via The Guardian.

- Macro International Inc. "2008. Ethiopia Atlas of Key Demographic and Health Indicators, 2005." (Calverton: Macro International, 2008) Archived 5 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 2, 3, 10 (Retrieved 30 September 2010)

- Overseas Security Advisory Council – Ethiopia 2007 Crime and Safety Report.

- Massages and manicures hit Addis Ababa Archived 15 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine by Tia Goldenberg. Retrieved 15 January 2010. IOL. 6 November 2007.

- "Company Profile Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine." Ethiopian Airlines. Retrieved on 3 October 2009.

- Sophie Eastaugh, for. "What makes Ethiopia the world's best spot for tourism?". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). "A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5. S2CID 508478.

- "5 Reasons to Visit Addis Ababa Now". www.fodors.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- "Crime in Addis Ababa". www.numbeo.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 1004-1007

- Solomon, Abiy. "Ethiopia building a Financial District in Addis Ababa". Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Lagasse, Paul (2018). The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press – via Credo Reference.

- Addis Today by Molalign GIRMA, 2014

- "Ethiopia Capital City, About Addis Ababa Tourism and Travel". Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- "INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MULTI-NATIONAL CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS: Addis Ababa Ring Road Project – A Case Study of a Chinese ..." Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Railway Gazette: Chinese funding for Addis Abeba light rail". Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Ethiopia: Addis' sister cities, historical ties". tuckmagazine.com. Tuck Magazine. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Harare, S. Korean city strengthen ties". pressreader.com. The Herald (Zimbabwe). 27 February 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Institute of Semitic Studies". instituteofsemiticstudies.org. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Mohammed Al Amoudi". Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Our Founder". soleRebels. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/loving/ruth-negga-profile/

Further reading

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History (Peoples of Africa). Wiley-Blackwell; New Ed edition. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Addis Ababa. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Addis Ababa. |