Garbage patch

A garbage patch is a gyre of marine debris particles caused by the effects of ocean currents and increasing plastic pollution by human populations. These human-caused collections of plastic and other debris, cause ecosystem and environmental problems that effect marine life, contaminate oceans with toxic chemicals, and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

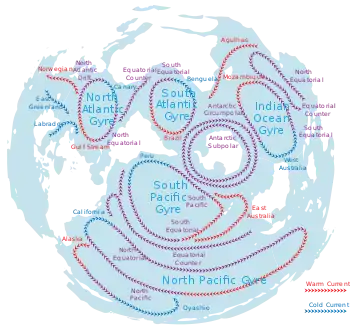

The best known of these is the Great Pacific garbage patch which has the highest density of marine debris and plastic, visible from space in certain weather conditions.[1] Other identified patches include the North Atlantic garbage patch between North America and Africa, the South Atlantic garbage patch located between eastern South America and the tip of Africa, the South Pacific garbage patch located west of South America, and the Indian Ocean garbage patch found east of south Africa listed in order of decreasing size.[2]

Garbage patches are rapidly growing because of widespread loss of plastic from human trash collection systems. It is estimated that approximately "100 million tons of plastic are generated [globally] each year", and about 10% of that plastic ends up in the oceans. The United Nations Environmental Program recently estimated that "for every square mile of ocean" there are about "46,000 pieces of plastic."[3]

Environmental issues

Photodegradation of plastics

The patch is one of several oceanic regions where researchers have studied the effects and impact of plastic photodegradation in the neustonic layer of water.[4] Unlike organic debris, which biodegrades, plastic disintegrates into ever smaller pieces while remaining a polymer (without changing chemically). This process continues down to the molecular level.[5] Some plastics decompose within a year of entering the water, releasing potentially toxic chemicals such as bisphenol A, PCBs and derivatives of polystyrene.[6]

As the plastic flotsam photodegrades into smaller and smaller pieces, it concentrates in the upper water column. As it disintegrates, the pieces become small enough to be ingested by aquatic organisms that reside near the ocean's surface. Plastic may become concentrated in neuston, thereby entering the food chain. Disintegration means that much of the plastic is too small to be seen. Moreover, plastic exposed to sunlight and in watering environments produce greenhouse gases, leading to further environmental impact.[7]

Effects on marine life

The United Nations Ocean Conference estimated that the oceans might contain more weight in plastics than fish by the year 2050.[8] Some long-lasting plastics end up in the stomachs of marine animals.[9][10][11] Plastic attracts seabirds and fish. When marine life consumes plastic allowing it to enter the food chain, this can lead to greater problems when species that have consumed plastic are then eaten by other predators.

Animals can also become trapped in plastic nets and rings, which can cause death. Plastic pollution affects at least 700 marine species, including sea turtles, seals and sea lions, seabirds, fish, and whales and dolphins.[12] Cetaceans have been sighted within the patch, which poses entanglement and ingestion risks to animals using the Great Pacific garbage patch as a migration corridor or core habitat.[13]

Plastic consumption

With the increased amount of plastic in the ocean, living organisms are now at a greater risk of harm from plastic consumption and entanglement. Approximately 23% of aquatic mammals, and 36% of seabirds have experienced the detriments of plastic presence in the ocean.[14] Since as much as 70% of the trash is estimated to be on the ocean floor, and microplastics are only millimeters wide, sealife at nearly every level of the food chain is affected.[15][16][17] Animals who feed off of the bottom of the ocean risk sweeping microplastics into their systems while gathering food.[18] Smaller marine life such as mussels and worms sometimes mistake plastic for their prey.[14][19]

Larger animals are also affected by plastic consumption because they feed on fish, and are indirectly consuming microplastics already trapped inside their prey.[18] Likewise, humans are also susceptible to microplastic consumption. People who eat seafood also eat some of the microplastics that were ingested by marine life. Oysters and clams are popular vehicles for human microplastic consumption.[18] Animals who are within the general vicinity of the water are also affected by the plastic in the ocean. Studies have shown 36% species of seabirds are consuming plastic because they mistake larger pieces of plastic for food.[14] Plastic can cause blockage of intestines as well as tearing of interior stomach and intestinal lining of marine life, ultimately leading to starvation and death.[14]

Entanglement

Not all marine life is affected by the consumption of plastic. Some instead find themselves tangled in larger pieces of garbage that cause just as much harm as the barely visible microplastics.[14] Trash that has the possibility of wrapping itself around a living organism may cause strangulation or drowning.[14] If the trash gets stuck around a ligament that is not vital for airflow, the ligament may grow with a malformation.[14] Plastic’s existence in the ocean becomes cyclical because marine life that is killed by it ultimately decompose in the ocean, re-releasing the plastics into the ecosystem.[20][21]

Identified patches

Great Pacific

The Great Pacific garbage patch, also described as the Pacific trash vortex is a garbage patch, a gyre of marine debris particles, in the central North Pacific Ocean. It is located roughly from 135°W to 155°W and 35°N to 42°N.[22] The collection of plastic and floating trash originates from the Pacific Rim, including countries in Asia, North America, and South America.[23] The gyre is divided into two areas, the "Eastern Garbage Patch" between Hawaii and California, and the "Western Garbage Patch" extending eastward from Japan to the Hawaiian Islands.

Despite the common public perception of the patch existing as giant islands of floating garbage, its low density (4 particles per cubic meter) prevents detection by satellite imagery, or even by casual boaters or divers in the area. This is because the patch is a widely dispersed area consisting primarily of suspended "fingernail-sized or smaller bits of plastic", often microscopic, particles in the upper water column known as microplastics.[24] Researchers from The Ocean Cleanup project claimed that the patch covers 1.6 million square kilometers.[25] Some of the plastic in the patch is over 50 years old, and includes items (and fragments of items) such as "plastic lighters, toothbrushes, water bottles, pens, baby bottles, cell phones, plastic bags, and nurdles." The small fibers of wood pulp found throughout the patch are "believed to originate from the thousands of tons of toilet paper flushed into the oceans daily."[24]

Research indicates that the patch is rapidly accumulating.[26] The patch is believed to have increased "10-fold each decade" since 1945.[27] A similar patch of floating plastic debris is found in the Atlantic Ocean, called the North Atlantic garbage patch.[28][29] This growing patch contributes to other environment damage to marine ecosystems and species.South Pacific

Indian Ocean

North Atlantic

References

- Parker, Laura. "With Millions of Tons of Plastic in Oceans, More Scientists Studying Impact." National Geographic. National Geographic Society, 13 June 2014. Web. 3 April 2016.

- Cózar, Andrés; Echevarría, Fidel; González-Gordillo, J. Ignacio; Irigoien, Xabier; Úbeda, Bárbara; Hernández-León, Santiago; Palma, Álvaro T.; Navarro, Sandra; García-de-Lomas, Juan; Ruiz, Andrea; Fernández-de-Puelles, María L. (2014-07-15). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (28): 10239–10244. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110239C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- Maser, Chris (2014). Interactions of Land, Ocean and Humans: A Global Perspective. CRC Press. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1482226393.

- Thompson, R. C.; Olsen, Y; Mitchell, RP; Davis, A; Rowland, SJ; John, AW; McGonigle, D; Russell, AE (2004). "Lost at Sea: Where is All the Plastic?". Science. 304 (5672): 838. doi:10.1126/science.1094559. PMID 15131299. S2CID 3269482.

- Barnes, D. K. A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R. C.; Barlaz, M. (2009). "Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 1985–98. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0205. JSTOR 40485977. PMC 2873009. PMID 19528051.

- Barry, Carolyn (20 August 2009). "Plastic Breaks Down in Ocean, After All – And Fast". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Royer, Sarah-Jeanne; Ferrón, Sara; Wilson, Samuel T.; Karl, David M. (2018-08-01). "Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment". PLOS ONE. 13 (8): e0200574. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200574. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6070199. PMID 30067755.

- Wright, Pam (6 June 2017). "UN Ocean Conference: Plastics Dumped In Oceans Could Outweigh Fish by 2050, Secretary-General Says". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Moore, Charles (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History Magazine.

- Holmes, Krissy (18 January 2014). "Harbour snow dumping dangerous to environment: biologist". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- "Jan Pronk". Public Radio International. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- "These 5 Marine Animals Are Dying Because of Our Plastic Trash… Here's How We Can Help". One Green Planet. 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- Gibbs, Susan E.; Salgado Kent, Chandra P.; Slat, Boyan; Morales, Damien; Fouda, Leila; Reisser, Julia (9 April 2019). "Cetacean sightings within the Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Biodiversity. 49 (4): 2021–27. doi:10.1007/s12526-019-00952-0.

- Sigler, Michelle (2014-10-18). "The Effects of Plastic Pollution on Aquatic Wildlife: Current Situations and Future Solutions". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 225 (11): 2184. doi:10.1007/s11270-014-2184-6. ISSN 1573-2932.

- Perkins, Sid (17 December 2014). "Plastic waste taints the ocean floors". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.16581.

- Handwerk, Brian (2009). "Giant Ocean-Trash Vortex Attracts Explorers". National Geographic.

- Ivar Do Sul, Juliana A.; Costa, Monica F. (2014-02-01). "The present and future of microplastic pollution in the marine environment". Environmental Pollution. 185: 352–364. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.036. ISSN 0269-7491. PMID 24275078.

- "Marine Plastics". Smithsonian Ocean. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- Kaiser, Jocelyn (2010-06-18). "The Dirt on Ocean Garbage Patches". Science. 328 (5985): 1506. doi:10.1126/science.328.5985.1506. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20558704.

- "Plastic pollution found inside dead seabirds". www.scotsman.com. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- "Pygmy sperm whale died in Halifax Harbour after eating plastic". CBC News. 16 March 2015.

- See the relevant sections below for specific references concerning the discovery and history of the patch. A general overview is provided in Dautel, Susan L. "Transoceanic Trash: International and United States Strategies for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch", 3 Golden Gate U. Envtl. L.J. 181 (2007)

- "World's largest collection of ocean garbage is twice the size of Texas". USA Today. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Philp, Richard B. (2013). Ecosystems and Human Health: Toxicology and Environmental Hazards, Third Edition. CRC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1466567214.

- Albeck-Ripka, Livia (22 March 2018). "The 'Great Pacific Garbage Patch' Is Ballooning, 87,000 Tons of Plastic and Counting". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A. (22 March 2018). "Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 4666. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.4666L. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5864935. PMID 29568057.

- Maser, Chris (2014). Interactions of Land, Ocean and Humans: A Global Perspective. CRC Press. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1482226393.

- Lovett, Richard A. (2 March 2010). "Huge Garbage Patch Found in Atlantic Too". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society.

- Victoria Gill (24 February 2010). "Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean". BBC. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- "South Pacific Gyre - Correntes Oceânicas". Google Sites.

- Barry, Carolyn (20 August 2009). "Plastic Breaks Down in Ocean, After All And Fast". National Geographic Society.

- First Voyage to South Atlantic Pollution Site SustainableBusiness.com News

- New garbage patch discovered in Indian Ocean, Lori Bongiorno, Green Yahoo, 27 July 2010]

- Opinion: Islands are 'natural nets' for plastic-choked seas Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Marcus Eriksen for CNN, Petroleum, CNN Tech 24 June 2010

- Our Ocean Backyard: Exploring plastic seas Archived 20 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Dan Haifley, 15 May 2010, Santa Cruz Sentinel

- Life aquatic choked by plastic 14 November 2010, Times Live

- Moore, Charles (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-07-06.

- Sesini, Marzia (August 2011). "The Garbage Patch In The Oceans: The Problem And Possible Solutions" (PDF). Columbia University.

- For a discussion of the current sampling techniques and particle size, see Peter Ryan, Charles Moore et al., Monitoring the abundance of plastic debris in the marine environment. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 27 July 2009 vol. 364 no. 1526 1999–2012, doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0207

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Transoceanic Trash: International and United States Strategies for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, Susan L. Dautel, 3 Golden Gate U. Envtl. L.J. 181 (2009)

- Carpenter, E.J.; Smith, K.L. (1972). "Plastics on the Sargasso Sea Surface, in Science". Science. 175 (4027): 1240–1241. doi:10.1126/science.175.4027.1240. PMID 5061243.

- "Mānoa: UH Mānoa scientist predicts plastic garbage patch in Atlantic Ocean | University of Hawaii News". manoa.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- Steve, By (4 August 2009). "Scientists study huge ocean garbage patch". Perthnow.com.au. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Scientists find giant plastic rubbish dump floating in the Atlantic". Perthnow.com.au. 26 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Gill, Victoria (24 February 2010). "Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean". BBC News. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Orcutt, Mike (2010-08-19). "How Bad Is the Plastic Pollution in the Atlantic?". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- Sigler, Michelle (2014-10-18). "The Effects of Plastic Pollution on Aquatic Wildlife: Current Situations and Future Solutions". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 225 (11): 2184. doi:10.1007/s11270-014-2184-6. ISSN 1573-2932.

- "The garbage patch territory turns into a new state - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". unesco.org.

- "About". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2019-11-08.