Getica

De origine actibusque Getarum (The Origin and Deeds of the Getae [Goths][n 1]),[1][2][3] commonly abbreviated Getica,[4] written in Late Latin by Jordanes in or shortly after 551 AD,[5][6] claims to be a summary of a voluminous account by Cassiodorus of the origin and history of the Gothic people, which is now lost.[7] However, the extent to which Jordanes actually used the work of Cassiodorus is unknown. It is significant as the only remaining contemporaneous resource that gives the full story of the origin and history of the Goths. Another aspect of this work is its information about the early history and the customs of the Slavs.

Synopsis of the work

The Getica begins with a geography/ethnography of the North, especially of Scandza (16-24). He lets the history of the Goths commence with the emigration of Berig with three ships from Scandza to Gothiscandza (25, 94), in a distant past. In the pen of Jordanes (or Cassiodorus), Herodotus' Getian demi-god Zalmoxis becomes a king of the Goths (39). Jordanes tells how the Goths sacked "Troy and Ilium" just after they had recovered somewhat from the war with Agamemnon (108). They are also said to have encountered the Egyptian pharaoh Vesosis (47). The less-fictional part of Jordanes' work begins when the Goths encounter Roman military forces in the 3rd century AD. The work concludes with the defeat of the Goths by the Byzantine general Belisarius. Jordanes concludes the work by stating that he writes to honour those who were victorious over the Goths after a history of 2030 years.

Importance and credibility

Because the original work of Cassiodorus has not survived, the work of Jordanes is one of the most important sources for the period of the migration of the European tribes, and the Ostrogoths and Visigoths in particular, from the 3rd century AD. Cassiodorus had claimed to have the Gothic "folk songs" — carmina prisca (Latin) — as an important source; recent scholarship regards this as highly questionable.[8] Its main purpose was to give the Gothic ruling class a glorious past, to match the past of the senatorial families of Roman Italy.

Jordanes stated that Getae are the same as the Goths, on the testimony of Orosius Paulus.[4] In a passage that has become controversial, he identifies the Venedi, a people mentioned by Tacitus, Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy, with the Slavs of the 6th century. Since as early as 1844,[9] this passage has been used by some scholars in eastern Europe to support the idea that there was a distinct Slavic ethnicity long before the last phase of the Late Roman period. Others have rejected this view because of the absence of concrete archaeological and historiographical data.[10]

The book is important to some medieval historians because it mentions the campaign in Gaul of one Riothamus, "King of the Brettones," a possible source of inspiration for the early stories of King Arthur.

One of the major questions concerning the historicity of the work is whether the identities mentioned are as ancient as Jordanes states or date from a later time. The evidence allows a wide range of views, the most skeptical being that the work is mainly mythological, or that, if Jordanes did exist and was the author, he described peoples of the 6th century only. According to the latter view, the credibility of his main source, Cassiodorus, is questionable for a number of reasons. First, a large part of the material was derived by culling ancient Greek and Latin authors for descriptions of peoples who might have been Goths.[11] Second, it seems that Jordanes distorted Cassiodorus's narrative by presenting a cursory abridgement of it mixed with 6th-century ethnic names.[12][13]

Some scholars claim that, while acceptance of Jordanes' text at face value may be too naive, a totally skeptical view is not warranted. For example, Jordanes writes that the Goths originated in Scandinavia in 1490 BC. One Austrian historian, Herwig Wolfram, believes that there might be a kernel of truth in the claim, if we assume that a clan of the Gutae left Scandinavia long before the establishment of the Amali in the leadership of the Goths. This clan might have contributed to the ethnogenesis of the Gutones in eastern Pomerania (see Wielbark culture).[14] Another example is the name of King Cniva, which David S. Potter thinks is genuine because, since it doesn't appear in the fictionalized genealogy of Gothic kings given by Jordanes, he must have found it in a genuine 3rd-century source.[15]

On the other hand, a Danish scholar, Arne Søby Christensen, claims that the Getica is an entirely fabricated account, and that the origin of the Goths that Jordanes outlines is a construction based on popular Greek and Roman myths, as well as misinterpretation of recorded names from Northern Europe. The purpose of this fabrication, according to Christensen, was to establish a glorious identity for the peoples that had recently gained power in post-Roman Europe.[16] A Canadian scholar, Walter Goffart, suggests another incentive, arguing that the Getica was part of a conscious plan by Justinian I and the propaganda machine at his court. He wanted to affirm that the Goths and their barbarian cousins did not belong to the Roman world, thus justifying the claims of the Eastern Roman Empire to hegemony over the western part.[17]

Editions

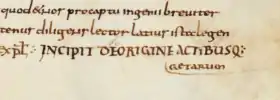

A manuscript of the text was rediscovered in Vienna in 1442 by the Italian humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini.[18] Its editio princeps was issued in 1515 by Konrad Peutinger, followed by many other editions.[19]

The classic edition is that of 19th-century German classical scholar Theodor Mommsen (in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, auctores antiqui, v. ii.). The best surviving manuscript was the Heidelberg manuscript, written in Heidelberg, Germany, probably in the 8th century, but this was destroyed in a fire at Mommsen's house on July 7, 1880. Subsequently, another 8th-century manuscript was discovered, containing chapters I to XLV, and is now the 'Codice Basile' at the Archivio di Stato in Palermo.[20] The next of the manuscripts in historical value are the Vaticanus Palatinus of the 10th century, and the Valenciennes manuscript of the 9th century.

Jordanes' work had been well known prior to Mommsen's 1882 edition. It was cited in Edward Gibbon's classic 6 volumes of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776), and had been earlier mentioned by Degoreus Whear (1623) who refers to both Jordanes' De regnorum ac temporum successione and to De rebus Geticis.[21]

Sources

In his Preface, Jordanes presents his plan

- "...to condense in my own style in this small book the twelve volumes of [Cassiodorus] Senator on the origin and deeds of the Getae [i.e. Goths] from olden times to the present day."

Jordanes admits that he did not then have direct access to Cassiodorus's book, and could not remember the exact words, but that he felt confident that he had retained the substance in its entirety. He goes on to say that he added relevant passages from Latin and Greek sources, composed the Introduction and Conclusion, and inserted various things of his own authorship. Due to this mixed origin, the text has been examined in an attempt to sort out the sources for the information it presents.

Jordanes himself

Former notarius to a Gothic magister militum Gunthigis, Jordanes would have been in a position to know traditions concerning the Gothic peoples without necessarily relying on anyone else. However, there is no evidence for this in the text, and some of the instances where the work refers to carmina prisca can be shown to depend on classical authors.[8]

Cassiodorus

Cassiodorus was a native Italian (Squillace, Bruttium), who rose to become advisor and secretary to the Gothic kings in various high offices. His and the Goths' most successful years were perhaps the reign of Theodoric. The policy of Theodoric's government at that time was reconciliation and in that spirit he incorporated Italians into the government whenever he could. He asked Cassiodorus to write a work on the Goths that would, in essence, demonstrate their antiquity, nobility, experience and fitness to rule.

Theodoric died in 526 and Cassiodorus went on to serve his successors in the same capacity. He had not by any means forgotten the task assigned to him by his former king. In 533 a letter ostensibly written by King Athalaric to the senate in Rome, but ghosted by Cassiodorus, mentions the great work on the Goths, now complete, in which Cassiodorus "restored the Amali with the illustriousness of their race." The work must have been written at Ravenna, seat of the Gothic kings, between 526 at latest and 533.

What Cassiodorus did with the manuscripts after that remains unknown. The fact that Jordanes once obtained them from a steward indicates that the wealthy Cassiodorus was able to hire at least one full-time custodian of them and other manuscripts of his; i.e., a private librarian (a custom not unknown even today).

Jordanes says in the preface to Getica that he obtained them from the librarian for three days in order to read them again (relegi). The times and places of these readings have been the concern of many scholars, as this information possibly bears on how much of Getica is based on Cassiodorus.

There are two main theories, one expressed by the Mierow source below, and one by the O'Donnell source below. Mierow's is earlier and does not include a letter cited by O'Donnell.[23]

Gothic sovereignty came to an end with the reconquest of Italy by Belisarius, military chief of staff for Justinian, ending in 539. Cassiodorus' last ghost writing for the Gothic kings was done for Witiges, who was removed to Constantinople in 540. A number of token kings ruled from there while Belisarius established that the Goths were not going to reinvade and retake Italy (which was however taken again by the Lombards after Justinian's death).

Cassiodorus retired in 540 to his home town of Squillace, where he used his wealth to build a monastery with school and library, Vivarium.

Authors cited by Getica

The events, persons and peoples of Getica are put forward as being up to many centuries prior to the time of Jordanes. Taken at face value, they precede any other history of Scandinavia.

Jordanes does cite some writers well before his time, to whose works he had access but we do not, and other writers whose works are still extant. Mierow gives a summary of these, which is reviewed below, and also states other authors he believed were used by Jordanes but were not cited in Getica (refer to the Mierow source cited below). Mierow's list of cited authors is summarized as follows:

- Ablabius. Otherwise unknown historian, author of the work Gothorum gentis ("of the Gothic people"), now lost.

- Dexippus on the Vandals and the Heruli.

- Dio, either Dio Cassius or Dio Chrysostom, author of another Getica. Description of Britain in Jordanes.

- Fabius. Otherwise unknown, author of a work including the siege of Ravenna, now missing.

- Josephus in IV.29, brief mention of the Goths as Scyths.

- Livy, brief mention in II.10.

- Lucan on the Amali, V.43.

- Pompeius Trogus, now known only in Justinus' epitome of Historiae Philippicae.

- Pomponius Mela.

- Priscus. Events concerning Attila.

- Ptolemy on Scandinavia in Getica Part III.

- Strabo. Authority on Britain.

- Symmachus. Copies of his copies from Julius Capitolinus on Maximinus.

- Tacitus. Authority on Britain.

- Virgil.

The Late Latin of Jordanes

The early Late Latin of Jordanes evidences a certain variability in the structure of the language which has been taken as an indication that the author no longer had a clear standard of correctness.[24] Jordanes tells us in Getica that he interrupted work on the Romana to write Getica, and then finished Romana. Jordanes states in Romana that he wrote it in the 24th year of the emperor Justinian, which began April 1, 551. In Getica he mentions a plague of nine years previous. This is probably the Plague of Justinian, which began in Egypt in 541, reached Constantinople in 542 and Italy in 543. The time is too early to identify a direction of change toward any specific Romance language, as none had appeared yet. This variability, however, preceded the appearance of the first French, Italian, Spanish, Romanian, etc. After those languages developed, the scholastics gradually restored classical Latin as a means of scholarly communication.

Jordanes refers to himself as agrammaticus before his conversion. This obscure statement is sometimes taken to refer to his Latin. Variability, however, characterizes all Late Latin, and besides, the author was not writing just after his conversion (for the meaning of the latter, see under Jordanes), but a whole career later, after associating with many Latin speakers and having read many Latin books. According to him, he should have been grammaticus by that time. More likely, his style reflects the way Latin was under the Goths.

Some of the variabilities are as follows (Mierow):

Orthography. The spelling of many words differs from the classical standard, which Jordanes would certainly have known. For example, Grecia replaces Graecia; Eoropam replaces Europam; Atriatici replaces Adriatici.

Inflection. Substantives migrate between declensions, verbs between conjugations. Some common changes are fourth to second (lacu to laco), second declension adjective to third (magnanimus to magnanimis), i-stems to non-i-stems (mari to mare in the ablative). Gender may change. Verbs may change voice.

One obvious change in a modern direction is the indeclinability of many formerly declined nouns, such as corpus. Also, the -m accusative ending disappears, leaving the preceding vowel or replacing it with -o (Italian, Romanian), as in Danubio for Danubium.

Syntax. Case variability and loss of agreement in prepositional phrases (inter Danubium Margumque fluminibus), change of participial tense (egressi [...] et transeuntes), loss of subjunctive in favor of indicative, loss of distinction between principal and subordinate clauses, confusion of subordinating conjunctions.

Semantics. Different vocabulary appears: germanus for frater, proprius for suus, civitas for urbs, pelagus for mare, etc.

Citations

- Costa 1977, p. 32.

- De Rebus Geticis: O. Seyffert, 329; De Getarum (Gothorum) Origine et Rebus Gestis

- Smith 1870, vol. 2, p.607.

- (Mierow 1908)

- Heather, Peter (1991), Goths and Romans 332-489, Oxford, pp. 47–49 (year 552)

- Goffart, Walter (1988), The Narrators of Barbarian History, Princeton, p. 98 (year 554)

- Wolfram 1988, Or in the original Die Goten (München 2001) , consistently uses Origo Gothica as a name not only for the work of Cassiodorus, but also, very confusingly, for the Getica. The source is Cassiodorus, Variae 9.25.5: "Originem Gothicam fecit esse historiam Romanam", which can be interpreted in different ways (see Goffart 2006, pp. 57–59). Cassiodorus' lost work is more commonly referred to as Historia Gothorum or History of the Goths by modern scholarship (Merrills 2005, pp. 102, 9)..

- Christensen 2002.

- Schafarik, Pavel Josef (1844), Slawiche Alterthümmer, 1, Leipzig, p. 40

- Curta 2001, p. 7; also pp.11-13 for an analysis of Schafarik's ideas in the context of his age as well as their revival by later Soviet historiography.

- Geary 2002, pp. 60-61.

- Curta 2001, p. 40.

- Goffart 2006, pp. 59-61.

- (Herwig 1988, p. 40), (Goffart 2006, pp. 59–61) harshly criticized this view

- Potter 2004, p. 245.

- Questia.com Review of Cassiodorus, Jordanes, and the History of the Goths: Studies in a Migration Myth by Peter S. Wells

- Goffart 2006, p. 70.

- Thomas & Gamble 1927, Pp vi, 202, 59.

- Smith 1870, "Jornandes".

- Lowe, C.L.A. XII.1741: 'saec. VIII, 2nd half'

- Degoreus Whear (1623), De Ratione Et Methodo Legendi Historias

- O'Donnell 2002, pp. 223-240.

- Croke, Brian (Apr 1987), "Cassiodorus and the Getica of Jordanes", Classical Philology, 82 (2): 117–134, doi:10.1086/367034

References

- Christensen, Arne Søby (2002), Cassiodorus, Jordanes, and the History of the Goths. Studies in a Migration Myth, ISBN 978-87-7289-710-3

- Costa, Gustavo (1977), Le antichità germaniche nella cultura italiana da Machiavelli a Vico, ISBN 88-7088-001-X

- Cristini, Marco (2020), "Vergil among the Goths: a Note on Iordanes, Getica 44", Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, 163: 235–240

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geary, Patric (2002), The Myth of Nations, the Medieval Origins of Europe, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11481-1

- Goffart, Walter (2006), Barbarian Tides, The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-39 39-3

- Mierow, Charles C., ed. (1908), Jordanes. The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, Princeton University , translation , e-text

- Mierow, Charles Christopher, ed. (1915), The Gothic History of Jordanes

- O'Donnell, James J (1982), "The Aims of Jordanes", Historia, 31: 223–240

- Potter, David Stone (2004), The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10058-5

- Seyffert, Oscar (1894), Nettleship, Henry; Sandys, J. E. (eds.), Dictionary of Classical Antiquities

- Smith, William (1870), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 2, archived from the original on 2007-04-05

- Thomas, William; Gamble, Miller (1927), The Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Its Inheritance in Source-valuation and Criticism, Washington: Catholic University of America

- Wolfram, Herwig (1988), History of the Goths, translated by Dunlap, Thomas J., University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06 983-8

- Merrills, A.H. (2005), History and Geography in Late Antiquity, Cambridge: CUP