Early Slavs

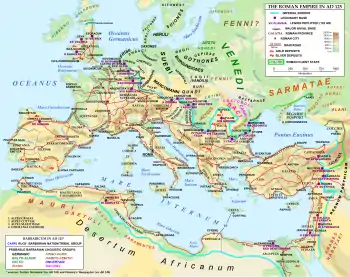

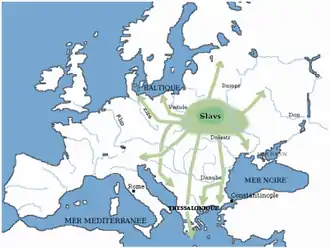

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the Slavic nations through the Slavic states of the High Middle Ages.[1] The first written use of the name "Slavs" dates to the 6th century, when the Slavic tribes inhabited a large portion of Central and Eastern Europe. By then, the nomadic Iranian ethnic groups living on the Eurasian Steppe (the Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans etc.) had been absorbed by the region's Slavic population.[2][3][4][5] Over the next two centuries, the Slavs expanded southwest toward the Balkans and the Alps and northeast towards the Volga River.[6] The Slavs' original habitation is still a matter of controversy, but scholars believe that it was somewhere in Eastern Europe.[7]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Beginning in the 9th century, the Slavs gradually converted to Christianity (both Byzantine Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism). By the 12th century, they were the core population of a number of medieval Christian states: East Slavs in the Kievan Rus', South Slavs in the Bulgarian Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia, Banate of Bosnia and the Grand Principality of Serbia, and West Slavs in the Great Moravia, the Kingdom of Poland, Duchy of Bohemia and Principality of Nitra. In the history the oldest known Slavic principality was Carantania, established in the 7th century by the Eastern Alpine Slavs, the ancestors of the present-day Slovenes. Slavic settlement of the Eastern Alps comprised modern-day Slovenia, Eastern Friul and large parts of modern Austria.

Origins

Ancient Roman and Greek historical sources refer to the early Slavic peoples as Veneti and Spori (allegedly from Greek σπείρω "I scatter grain") in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and later in the 5th and 6th centuries also as Antes and Sclaveni. The 6th-century Byzantine historian Jordanes referred to the Slavs in his 551 work Getica, reporting that "although they derive from one nation, now they are known under three names, the Veneti, Antes and Sclaveni" (ab unastirpe exorti, tria nomina ediderunt, id est Veneti, Antes, Sclaveni).[8] Procopius wrote in 545 that "the Sclaveni and the Antae actually had a single name in the remote past; for they were both called Sporoi in olden times".[9] Later, in the 8th century during the Early Middle Ages, early Slavs living on the borders of the Carolingian Empire were referred to as Wends.[10][11]

Early Slavic archaeological findings are most often associated with the Przeworsk and Zarubintsy cultures, with evidence ranging from hill forts, ceramic pots, weapons, jewelry and abodes. However, in many areas archaeologists face difficulties in distinguishing Slavic and non-Slavic findings since the early Slavic culture over the subsequent centuries was heavily influenced by the Sarmatian culture from the east and by the various Germanic cultures from the west. [12]

Homeland

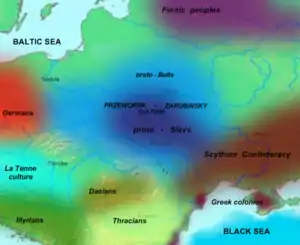

The Proto-Slavic homeland is the area of Slavic settlement in Central and Eastern Europe during the first millennium AD, with its precise location debated by archaeologists, ethnographers and historians.[13] Most scholars consider Polesia the homeland of the Slavs.[14] Theories attempting to place Slavic origin in the Near East have been discarded.[13] None of the proposed homelands reaches the Volga River in the east, over the Dinaric Alps in the southwest or the Balkan Mountains in the south, or past Bohemia in the west.[15][16]

Frederik Kortlandt has suggested that the number of candidates for Slavic homeland may rise from a tendency among historians to date "proto-languages farther back in time than is warranted by the linguistic evidence". Although all spoken languages change gradually over time, the absence of written records allows change to be identified by historians only after a population has expanded and separated long enough to develop daughter languages.[17] The existence of an "original home" is sometimes rejected as arbitrary[18] because the earliest origin sources "always speak of origins and beginnings in a manner which presupposes earlier origins and beginnings".[19]

According to historical records, the Slavic homeland would have been somewhere in Central Europe, possibly along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. The Prague-Penkova-Kolochin complex of cultures of the 6th and the 7th centuries AD is generally accepted to reflect the expansion of Slavic-speakers at the time.[20] Core candidates are cultures within the territories of modern Belarus, Poland and Ukraine. According to the Polish historian Gerard Labuda, the ethnogenesis of Slavic people is the Trzciniec culture[21] from about 1700 to 1200 BC. The Milograd culture hypothesis posits that the pre-Proto-Slavs (or Balto-Slavs) originated in the 7th century BC–1st century AD culture of northern Ukraine and southern Belarus. According to the Chernoles culture theory, the pre-Proto-Slavs originated in the 1025–700 BC culture of northern Ukraine and the 3rd century BC–1st century AD Zarubintsy culture. According to the Lusatian culture hypothesis, they were present in northeastern Central Europe in the 1300–500 BC culture and the 2nd century BC–4th century AD Przeworsk culture. The Danube basin hypothesis, postulated by Oleg Trubachyov[22] and supported by Florin Curta and Nestor's Chronicle, theorises that the Slavs originated in central and southeastern Europe.

The latest attempt of locating the place of Slavic origin used genetics and studied the paternal lineages of all existing modern Slavic populations. It placed the earliest known homeland of Slavs within the area of the middle Dnieper basin, in present-day Ukraine.[23]

Linguistics

Proto-Slavic began to evolve from Proto-Indo-European,[25] the reconstructed language from which originated a number of languages spoken in Eurasia.[26][27] The Slavic languages share a number of features with the Baltic languages (including the use of genitive case for the objects of negative sentences, Proto-Indo-European kʷ and other labialized velars), which may indicate a common Proto-Balto-Slavic phase in the development of those two linguistic branches of Indo-European.[26][27] Frederik Kortlandt places the territory of the common language near the Indo-European homeland: "The Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations became speakers of Balto-Slavic".[28] However, "geographical contiguity, parallel development and interaction" may explain the existence of the characteristics of both language groups.[27]

Proto-Slavic developed into a separate language during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC.[25] The Proto-Slavic vocabulary, which was inherited by its daughter languages, described its speakers' physical and social environment, feelings and needs.[29][30] Proto-Slavic had words for family connections, including svekry ("husband's mother"), and zъly ("sister-in-law").[31] The inherited Common Slavic vocabulary lacks detailed terminology for physical surface features that are peculiar to mountains or the steppe, the sea, coastal features, littoral flora or fauna or saltwater fish.[32]

Proto-Slavic hydronyms have been preserved between the source of the Vistula and the middle basin of the Dnieper.[33] Its northern regions adjoin territory in which river names of Baltic origin (Daugava, Neman and others) abound.[34][35] On the south and east, it borders the area of Iranian river names (including the Dniester, the Dnieper and the Don).[36] A connection between Proto-Slavic and Iranian languages is also demonstrated by the earliest layer of loanwords in the former;[29] the Proto-Slavic words for god (*bogъ), demon (*divъ), house (*xata), axe (*toporъ) and dog (*sobaka) are of Scythian origin.[37] The Iranian dialects of the Scythians and the Sarmatians influenced Slavic vocabulary during the millennium of contact between them and early Proto-Slavic.[38]

A longer, more intensive connection between Proto-Slavic and the Germanic languages can be assumed from the number of Germanic loanwords, such as *duma ("thought"), *kupiti ("to buy"), *mĕčь ("sword"), *šelmъ ("helmet") and *xъlmъ ("hill").[39] The Common Slavic words for beech, larch and yew were also borrowed from Germanic, which led Polish botanist Józef Rostafiński to place the Slavic homeland in the Pripet Marshes, which lacks those plants.[40] Germanic languages were a mediator between Common Slavic and other languages; the Proto-Slavic word for emperor (*cĕsar'ь) was transmitted from Latin through a Germanic language, and the Common Slavic word for church (*crъky) came from Greek.[39]

Common Slavic dialects before the 4th century AD cannot be detected since all of the daughter languages emerged from later variants.[41] Tonal word stress (a 9th-century AD change) is present in all Slavic languages, and Proto-Slavic reflects the language that was probably spoken at the end of the 1st millennium AD.[41]

Historiography

Jordanes, Procopius and other Late Roman authors provide the probable earliest references to the southern Slavs in the second half of the 6th century AD.[42] Jordanes completed his Gothic History, an abridgement of Cassiodorus's longer work, in Constantinople in 550 or 551.[43][44] He also used additional sources: books, maps or oral tradition.[45]

Jordanes wrote that the Venethi, Sclavenes and Antes were ethnonyms that referred to the same group.[46] His claim was accepted more than a millennium later by Wawrzyniec Surowiecki, Pavel Jozef Šafárik and other historians,[47] who searched the Slavic Urheimat in the lands that the Venethi (a people named in Tacitus's Germania)[48] lived during the last decades of the 1st century AD.[49] Pliny the Elder wrote that the territory extending from the Vistula to Aeningia (probably Feningia, or Finland), was inhabited by the Sarmati, Wends, Scirii and Hirri.[50]

Procopius completed his three works on Emperor Justinian I's reign (Buildings, History of the Wars, and Secret History) during the 550s.[51][52] Each book contains detailed information on raids by Sclavenes and Antes on the Eastern Roman Empire,[53] and the History of the Wars has a comprehensive description of their beliefs, customs and dwellings.[54][55] Although not an eyewitness, Procopius had contacts among the Sclavene mercenaries who were fighting on the Roman side in Italy.[54]

Agreeing with Jordanes's report, Procopius wrote that the Sclavenes and Antes spoke the same languages but traced their common origin not to the Venethi but to a people he called "Sporoi".[56] Sporoi ("seeds" in Greek; compare "spores") is equivalent to the Latin semnones and germani ("germs" or "seedlings"), and the German linguist Jacob Grimm believed that Suebi meant "Slav".[57] Jordanes and Procopius called the Suebi "Suavi". The end of the Bavarian Geographer's list of Slavic tribes contains a note: "Suevi are not born, they are sown (seminati)".[58] The language spoken by Tacitus's Suevi is unknown. In his description of the emigration (c. 512) of the Heruli to Scandinavia, Procopius places the Slavs in Central Europe.

A similar description of the Sclavenes and Antes is found in the Strategikon of Maurice, a military handbook written between 592 and 602 and attributed to Emperor Maurice.[59] Its author, an experienced officer, participated in the Eastern Roman campaigns against the Sclavenes on the lower Danube at the end of the century.[60] A military staff member was also the source of Theophylact Simocatta's narrative of the same campaigns.[61]

Although Martin of Braga was the first western author to refer to a people known as "Sclavus" before 580, Jonas of Bobbio included the earliest lengthy record of the nearby Slavs in his Life of Saint Columbanus (written between 639 and 643).[62] Jonas referred to the Slavs as "Veneti" and noted that they were also known as "Sclavi".[63]

Western authors, including Fredegar and Boniface, preserved the term "Venethi".[64] The Franks (in the Life of Saint Martinus, the Chronicle of Fredegar and Gregory of Tours), Lombards (Paul the Deacon) and Anglo-Saxons (Widsith) referred to Slavs in the Elbe-Saale region and Pomerania as "Wenden" or "Winden" (see Wends). The Franks and the Bavarians of Styria and Carinthia called their Slavic neighbours "Windische".

The unknown author of the Chronicle of Fredegar used the word "Venedi" (and variants) to refer to a group of Slavs who were subjugated by the Avars.[63] In the chronicle, "Venedi" formed a state that emerged from a revolt[63] led by the Frankish merchant Samo against the Avars around 623.[65] A change in terminology, the replacement of Slavic tribal names for the collective "Sclavenes" and "Antes", occurred at the end of the century;[66] the first tribal names were recorded in the second book of the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, around 690.[67] According to Florin Curta, the change indicates pre-existing differences among Slavic groups. Although "Sclavene" may have originally been the ethnonym of a particular ethnic group, it became "a purely Byzantine construct ... an umbrella term for various groups living north of the Danube frontier, which were neither 'Antes', nor 'Huns' or 'Avars'."[68] The unknown "Bavarian Geographer" listed Slavic tribes in the Frankish Empire around 840,[53] and a detailed description of 10th-century tribes in the Balkan Peninsula was compiled under the auspices of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in Constantinople around 950.[69]

Archaeology

In the archaeological literature, attempts have been made to assign an early Slavic character to several cultures in a number of time periods and regions.[70] The Prague-Korchak cultural horizon encompasses postulated early Slavic cultures from the Elbe to the Dniester, in contrast with the Dniester-to-Dnieper Penkovka culture. "Prague culture" refers to western Slavic material grouped around Bohemia, Moravia and western Slovakia, distinct from the Mogilla (southern Poland) and Korchak (central Ukraine and southern Belarus) groups further east. The Prague and Mogilla groups are seen as the archaeological reflection of the 6th-century Western Slavs.[71]

The 2nd-to-5th-century Chernyakhov culture encompassed modern Ukraine, Moldova and Wallachia. Chernyakov finds include polished black-pottery vessels, fine metal ornaments and iron tools.[72] Soviet scholars, such as Boris Rybakov, saw it as the archaeological reflection of the proto-Slavs.[73] The Chernyakov zone is now seen as representing the cultural interaction of several peoples, one of which was rooted in Scytho-Sarmatian traditions, which were modified by Germanic elements that were introduced by the Goths.[72][74] The semi-subterranean dwelling with a corner hearth later became typical of early Slavic sites,[75] with Volodymir Baran calling it a Slavic "ethnic badge".[75] In the Carpathian foothills of Podolia, at the northwestern fringes of the Chernyakov zone, the Slavs gradually became a culturally-unified people; the multiethnic environment of the Chernyakhov zone presented a "need for self-identification in order to manifest their differentiation from other groups".[76]

The Przeworsk culture, northwest of the Chernyakov zone, extended from the Dniester to the Tisza valley and north to the Vistula and Oder.[77] It was an amalgam of local cultures, most with roots in earlier traditions modified by influences from the (Celtic) La Tène culture, (Germanic) Jastorf culture beyond the Oder and the Bell-Grave culture of the Polish plain. The Venethi may have played a part; other groups included the Vandals, Burgundians and Sarmatians.[77] East of the Przeworsk zone was the Zarubinets culture, which is sometimes considered part of the Przeworsk complex.[78] Early Slavic hydronyms are found in the area occupied by the Zarubinets culture,[78] and Irena Rusinova proposed that the most prototypical examples of Prague-type pottery later originated there.[75] The Zarubinets culture is identified as proto-Slavic[79] or an ethnically-mixed community that became Slavicized.[80]

With increasing age, the confidence with which archaeological connections can be made to known historic groups lessens.[81] The Chernoles culture has been seen as a stage in the evolution of the Slavs,[78] and Marija Gimbutas identified it as the proto-Slavic homeland.[82] According to many pre-historians, ethnic labels are inappropriate for European Iron Age peoples.[83]

The Globular Amphora culture stretched from the middle Dnieper to the Elbe during the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BC. It has been suggested as the locus of a Germano-Balto-Slavic continuum (the Germanic substrate hypothesis), but the identification of its bearers as Indo-Europeans is uncertain. The area of the culture contains a number of tumuli, which are typical of Indo-Europeans.

The 8th-to-3rd-century BC Chernoles culture, sometimes associated with Herodotus' "Scythian farmers", is "sometimes portrayed as either a state in the development of the Slavic languages or at least some form of late Indo-European ancestral to the evolution of the Slavic stock".[84] The Milograd culture (700 BC–100 AD), centred roughly in today's Belarus and north of the Chernoles culture, has also been proposed as ancestral for the Slavs or the Balts. The ethnic composition of the Przeworsk culture (2nd century BC to 4th century AD), associated with the Lugii) of central and southern Poland, northern Slovakia and Ukraine, including the Zarubintsy culture (2nd century BC to 2nd century AD and connected with the Bastarnae tribe) and the Oksywie culture are other candidates.

Southern Ukraine is known to have been inhabited by Scythian and Sarmatian tribes before the Goths. Early Slavic stone stelae that are found in the middle Dniester region are markedly different from the Scythian and Sarmatian stelae of the Crimea.

The Wielbark culture displaced the eastern Oksywie culture during the 1st century AD. Although the 2nd-to-5th-century Chernyakhov culture triggered the decline of the late Sarmatian culture from the 2nd to the 4th centuries, the western part of the Przeworsk culture remained intact until the 4th century and the Kiev culture flourished from the 2nd to the 5th centuries and is recognised as the predecessor of the 6th- and 7th-century Prague-Korchak and Pen'kovo cultures, the first archaeological cultures that are identified as Slavic. Although Proto-Slavic probably reached its final stage in the Kiev area, the scientific community disagrees on the Kiev culture's predecessors. Some scholars trace them from the Ruthenian Milograd culture, others from the Ukrainian Chernoles and Zarubintsy cultures and still others from the Polish Przeworsk culture.

Ethnogenesis

The Slavic population of eastern Europe expanded during the sixth century, bringing their customs and language. Although there is no consensus about their homeland, scholars generally looked north of the Carpathians. Russian archaeologist Valentin Sedov, using the Herderian concept of nationhood,[85] proposed that the Venethi were the proto-Slavic bearers of the Przeworsk culture. Their expansion began during the second century AD, and they occupied a large area of eastern Europe between the Vistula and the middle Dnieper. The Venethi slowly expanded south and east by the fourth century, assimilating the neighbouring Zarubinec culture (which Sedov considered partly Baltic) and continuing southeast to become part of the Chernyakhov culture. The Antes separated themselves from the Venethi by 300 (followed by the Sclaveni by 500) in the areas of the Penkovka and Prague-Korchak cultures, respectively.[86]

During the seventh century BC, the Chernoles culture was loosely governed by the Scythians via trade. There was limited interaction between the Slavs, who were tribute-paying ploughmen under the Scythians, and the nomads. Their homeland in the forest steppe enabled them to preserve their language, except for phonetic and some lexical constituents and their patrilineal, agricultural customs.[87] After a millennium, when the Hunnic Empire collapsed, an eastern-Slavic culture re-emerged and spread rapidly in the south and central-eastern Europe. According to Marija Gimbutas, "Neither Bulgars nor Avars colonized the Balkan Peninsula; after storming Thrace, Illyria and Greece they went back to their territory north of the Danube. It was the Slavs who did the colonizing ... entire families or even whole tribes infiltrated lands. As an agricultural people, they constantly sought an outlet for the population surplus. Suppressed for over a millennium by foreign rule of Scythians, Sarmatians and Goths, they had been restricted to a small territory; now the barriers were down and they poured out".[88] In addition to their growth, the depopulation of eastern Europe (due, in part, to Germanic migration) and the lack of imperial defences encouraged Slavic expansion.[89]

With processual archaeology during the 1960s, scholars began to believe that "there was no need to explain culture change exclusively in terms of migration and population replacement".[90] According to historical linguist Johanna Nichols, "Ethnic spreads can involve either the spread of a language to speakers of other languages or the spread of a population. Massive population spread or demographic replacement has probably been a rarity in human history... There is no reason to assume that the Slavic expansion was a primarily demographic event. Some migration took place, but the parsimonious assumption is the Slavic expansion was primarily a linguistic spread".[91] Colin Renfrew proposed elite-dominance and system-collapse theories to explain language replacement.

Pavel Dolukhanov suggested that their experience with nomads enabled the Slavs political and military experience, becoming a "dominant force and establishing a new socio-political network in the entire area of central and southeastern Europe".[92] According to Paul Barford, "The Spartan and egalitarian (Slavic) culture ... clearly had something attractive for great numbers of the populations living over considerable areas of central Europe", resulting in their assimilation. "The analysis of Slav material culture (especially South Slavs) and results of anthropological investigations, as well as the loan-words in philological studies, clearly demonstrate the contribution of the previous populations of these territories in the make-up of some of the Slav populations".[93]

Byzantine chroniclers noted that Roman prisoners captured by the Sclavenes could soon become free members of Slavic society if they wished.[93] Horace Lunt attributed Slavic spread to the "success and mobility of the Slavic 'special border guards' of the Avar khanate",[94] (military elites), who used it as a lingua franca in the Avar Khanate. According to Lunt, only as a lingua franca could Slavic supplant other languages and dialects whilst remaining relatively uniform. Although it explains the formation of regional Slavic groups in the Balkans, eastern Alps and the Morava-Danube basin, Lunt's theory does not account for Slavic spread to the Baltic region and the territory of the Eastern Slavs (areas with no historical links to the Avar Khanate):[95]

A concept related to elite dominance is system collapse, where a power vacuum created by the fall of the Hun and Roman Empires allows a minority group to impose their customs and language.[96] Paul Barford suggested that Slavic groups might have existed in a wide area of central-eastern Europe (in the Chernyakov and Zarubintsy-Przeworsk cultural zones) before the documented Slavic migrations from the sixth to the ninth centuries. Serving as auxiliaries in the Sarmatian, Goth and Hun armies, small numbers of Slavic speakers might have reached the Balkans before the sixth century:[97] These scattered groups were centers for the creation of a Slavic cultural identity under favorable conditions, assimilating or conveying their culture and language.

A similar idea has been proposed by Florin Curta. Seeing no clear evidence for a migration from Polesia or elsewhere north, Curta suggests that southeastern Europe saw the development of a "broad area of common economic and cultural traditions ... Whether living within the same region or widely scattered, adherence to this style helped to integrate isolated individuals within a group whose social boundaries crisscrossed those of local communities".[98] "During the early 600s, however, at the time of the general collapse of the Byzantine administration in the Balkans, access to and manipulation of such (Slavic) artifacts may have been strategies for creating a new sense of identity for local elites". Curta suggests that the chief impetus for this identity originated in the Danubian frontier.

Scholars acknowledge that an attempt to define a localized Slavic homeland may be simplistic. Although proto-Slavic may have developed in a localized area, Slavic ethnogenesis occurred in a large area, from the Oder in the west to the Dnieper in the east and south to the Danube.[98][99] It was a complex process, fueled by changes in the Barbaricum and the Roman Empire. Despite cultural uniformity, Slavic development seems to have been less politically consolidated than that of the Germanic peoples.

According to Patrick Geary, Slavic expansion was a decentralized-but-forceful process which assimilated a large population with small groups of "soldier-farmers" who had common traditions and language: "Without kings or large–scale chieftains to bribe or defeat, the Byzantine Empire had little hope of either destroying them or co-opting them into the imperial system".[99] Walter Pohl agrees: "Avars and Bulgars conformed to the rules of the game established by the Romans. They built up a concentration of military power that was paid, in the last resort, from Roman tax revenues. Therefore they paradoxically depended on the functioning of the Byzantine state. The Slavs managed to keep up their agriculture (and a rather efficient kind of agriculture, by the standards of the time), even in times when they took their part in plundering Roman provinces. The booty they won apparently did not (at least initially) create a new military class with the greed for more and contempt for peasant's work, as it did with the Germans. Thus the Slavic model proved an attractive alternative ... which proved practically indestructible. Slav traditions, language, and culture shaped, or at least influenced, innumerable local and regional communities: a surprising similarity that developed without any central institution to promote it. These regional ethnogeneses inspired by Slavic tradition incorporated considerable remnants of the Roman or Germanic population ready enough to give up ethnic identities that had lost their cohesion".[100]

Appearance

Procopius described that the Slavs "are all exceptionally tall and stalwart men, while their bodies and hair are neither very fair or very blonde, nor indeed do they incline entirely to the dark type, but they are slightly ruddy in color... they are neither dishonorable nor spiteful, but simple in their ways, like the Huns [Avars]... some of them do not have either a tunic or cloak, but only wear a kind of breeches pulled up to the groin".[101] Jordanes wrote "all of them are tall and very strong... their skin and hair are neither very dark nor light, but are ruddy of face".[102] Abraham ben Jacob, in the 10th century, wrote that "what is peculiar, most of Bohemian [Czech] people are of swarthy complexion and dark hair, while fair colors are rare among them".

Society

Early Slavic society was a typical decentralised tribal society of Iron Age Europe and was organised into local chiefdoms. A slow consolidation occurred between the 7th and the 9th, when the previously-uniform Slavic cultural area evolved into discrete zones. Slavic groups were influenced by neighbouring cultures like Byzantium, the Khazars, the Vikings and the Carolingians and influenced their neighbours in return.[103]

Differences in status gradually developed in the chiefdoms, which led to the development of centralized socio-political organisations. The first centralized organisations may have been temporary pantribal warrior associations, the greatest evidence being in the Danubian area, where barbarian groups organised around military chiefs to raid Byzantine territory and to defend themselves against the Pannonian Avars.[104] Social stratification gradually developed in the form of fortified, hereditary chiefdoms, which were first seen in the West Slavs areas. The chief was supported by a retinue of warriors, who owed their position to him. As chiefdoms became powerful and expanded, centres of subsidiary power ruled by lesser chiefs were created, and the line between powerful chiefdoms and centralised medieval states is blurred. By the mid-9th century, the Slavic elite had become sophisticated; it wore luxurious clothing, rode horses, hunted with falcons and travelled with retinues of soldiers.[105]

Settlements

Early Slavic settlements were no larger than 0.5 to 2 hectares (1.2 to 4.9 acres). Settlements were often temporary, perhaps reflected their itinerant form of agriculture,[106] and were often along rivers. They were characterised by sunken buildings, known as Grubenhäuser in German or poluzemlianki in Russian. Built over a rectangular pit, they varied from 4 to 20 m2 (43 to 215 sq ft) in area and could accommodate a typical nuclear family. Each house had a stone or clay oven in a corner (a defining feature of Eastern European dwellings), and a settlement had a population of fifty to seventy.[107] Settlements had a central, open area in which communal activities and ceremonies were conducted, and they were divided into production and settlement zones.[108]

Strongholds appeared during the 9th century, especially the Western Slavic territories, and were often found in the centre of a group of settlements. The South Slavs did not form enclosed strongholds but lived in open, rural settlements that were adopted from the social models of the indigenous populations they encountered.

Tribal and territorial organisation

There is no indication of Slavic chiefs in any of the Slavic raids before AD 560, when Pseudo-Caesarius's writings mentioned their chiefs but described the Slavs as living by their own law and without the rule of anyone.[109]

The Sclaveni and the Antes were reported to have lived under a democracy for a long time.[110] The 6th-century historian Procopius, who was in contact with Slavic mercenaries,[111] reported, "For these nations, the Sclaveni and the Antes, are not governed by one man, but from ancient times have lived in democracy, and consequently everything which involves their welfare, whether for good or for ill, is referred to the people".[112] The 6th-century Strategikon of Maurice is considered an eyewitness of the Slavs and recommended the Roman generals to use any possible means to prevent the Sclaveni from uniting "under one ruler" and added that "the Sclaveni and Antes were both independent, absolutely refused to be enslaved or governed, least of all in their own land".[113]

Settlements were not uniformly distributed but were in clusters separated by areas of lower settlement density.[114] The clusters resulted from the expansion of single settlements, and the "settlement cells" were linked by familial or clan relationships. Settlement cells were the basis of the simplest form of territorial organization, known as a župa in South Slavic and opole in Polish. According to the Primary Chronicle, "The men of the Polanie lived each with his own clan in his own place". Several župas, encompassing individual clan territories, formed the known tribes: "The complex processes initiated by the Slav expansion and subsequent demographic and ethnic consolidation culminated in the formation of tribal groups, which later coalesced to create state which form the framework of the ethnic make-up of modern eastern Europe".[115]

The root of many tribal names denotes the territory in which they inhabited, such as the Milczanie (who lived in areas with měl – loess), Moravians (along the Morava), Diokletians (near the former Roman city of Doclea) and Severiani (northerners). Other names have more general meanings, such as the Polanes (pola; field) and Drevlyans (drevo; tree). Others appear to have a non-Slavic (possibly Iranian) root, such as the Antes, Serbs and Croats. Some geographically-distant tribes appear to share names. The Dregoviti appear north of the Pripyat River and in the Vardar valley, the Croats in Galicia and northern Dalmatia and the Obodrites near Lübeck and their further south in Pannonia. The root Slav was retained in the modern names of the Slovenes, Slovaks and Slavonians. There is little evidence of migratory links between tribes sharing the same name. The common names may reflect names given the tribes by historians or a common tongue as a distinction between Slavs (slovo; word, letter) and others, Nemci (mutes) being a Slavic name for "Germans".

The first historical Slavic state, founded by Samo in the first half of the 7th century, a short-lived tribal union that included parts of Central Europe, followed by the Bulgarian Empire in 681. By the 9th century, the states of Obotrites, Great Moravia, Carantania, Lower Pannonia, Croatia, Serbia had emerged.

Marriage

Capturing wives and exogamy were traditions among the tribes and continued until the early medieval era. However, on some occasions in Bohemia and the Ukraine, it was women who chose the spouse.[116] Fornication had a sentence in Pagan Slavs that was described as capital punishment by travelers, Ibn-Fadlan: "Men and women go to the river and bathe together naked... but they do not fornicate and if anyone would be guilty of it, no matter who is he and she... he and she would be pinked by pole-axe... then they hang out each part both of them on a tree", Gardizi: "If someone makes fornication, he or she would be killed, without accepting any apologies".[117]

Warfare

Early barbarian warrior bands, typically numbering 200 or less, were intended for fast penetration into enemy territory and an equally-quick withdrawal. In Wars VII.14, 25, Procopius wrote that the Slavs "fight on foot, advancing on the enemy; in their hands they carry small shields and spears, but they never wear body armour". According to the Strategikon, the Slavs favoured ambush and guerrilla tactics and often attacked their enemy's flank: "They are armed with short spears; each man carries two, one of them with a large shield". Sources also mentioned the use of cavalry. Theophylact Simocatta wrote that the Slavs "dismounted from their horses in order to cool themselves" during a raid,[118] and Procopius wrote that Slav and "Hun" horsemen were Byzantine mercenaries.[119] In their dealings with the Sarmatians and Huns, the Slavs may have become skilled horsemen, an explanation for their expansion.[120] According to the Strategikon (XI.4.I-45), the Slavs were a hospitable people and did not keep prisoners indefinitely "but lay down a certain period after which they can decide for themselves if they want to return to their former homelands after paying a ransom, or to stay amongst the Slavs as free men and friends".

Religion

Little is known about Slavic religion before the Christianization of Bulgaria and of Kievan Rus. After Christianization, Slavic authorities destroyed many records of the old religion. Some evidence remains in apocryphal and devotional texts,[121] the etymology of Slavic religious terms[122] and the Primary Chronicle.[123]

Early Slavic religion was relatively uniform:[124] animistic, anthropomorphic[125] and inspired by nature.[126] The Slavs developed cults around natural objects, such as springs, trees or stones, out of respect for the spirit (or demon) within.[127] Slavic pre-Christian religion was originally polytheistic, with no organised pantheon.[128] Although the earliest Slavs seemed to have a weak concept of God, the concept evolved[129] into a form of monotheism in which a "supreme god [ruled] in heaven over the others".[130] There is no evidence of a belief in fate[131] or predestination.[132]

Pre-Christian Slavic spirits and demons could be entities in their own right or spirits of the dead and were associated with home or nature. Forest spirits, entities in their own right, were venerated as the counterparts of home spirits, which were usually related to ancestors.[133] Demons and spirits were good or evil, which suggests that the Slavs had a dualistic cosmology and are known to have revered them with sacrifices and gifts.[134]

Slavic paganism was syncretistic[135] and combined and shared with other religions, including Germanic paganism.[136] Linguistic evidence indicates that part of Slavic paganism developed when the Balts and Slavs shared a common language[124] since pre-Christian Slavic beliefs contained elements also found in Baltic religions. After the Slavic and the Baltic languages diverged, the early Slavs interacted with Iranian peoples and incorporated elements of Iranian spirituality. Early Iranian and Slavic supreme gods were considered givers of wealth, unlike the supreme thunder gods of other European religions. Both Slavs and Iranians had demons, with names from similar linguistic roots (Iranian Daêva and Slavic Divŭ) and a concept of dualism: good and evil.[130][137]

Although evidence of pre-Christian Slavic worship is scarce (suggesting that it was aniconic), religious sites and idols are most plentiful in Ukraine and Poland. Slavic temples and indoor places of worship are rare since outdoor places of worship are more common, especially in Kievan Rus'. The outdoor cultic sites were often on hills and included ringed ditches.[138] Indoor shrines existed: "Early Russian sources... refer to pagan shrines or altars known as kapishcha" and were small, enclosed structures with an altar inside. One was found in Kiev, surrounded by the bones of sacrificed animals.[139] Pagan temples were documented as destroyed during Christianization.[140]

Records of pre-Christian Slavic priests, like the pagan temples, appeared later.[140] Although no early evidence of Slavic pre-Christian priests has been found, the prevalence of sorcerers and magicians after Christianization suggests that the pre-Christian Slavs had religious leaders.[141] Slavic pagan priests were believed to commune with the gods, to predict the future[132] and to prepare for religious rituals. The pagan priests, or magicians (known as volkhvy by the Rus' people),[123] resisted Christianity[142] after Christianization. The Primary Chronicle describes a campaign against Christianity in 1071 during a famine. The volkhvy were well-received nearly 100 years after Christianization, which suggested that pagan priests had an esteemed position in 1071 and in pre-Christian times.[143]

Although the Slavic funeral pyre was seen as a means of freeing the soul from the body rapidly, visibly and publicly,[144] archaeological evidence suggests that the South Slavs quickly adopted the burial practices of their post-Roman Balkan neighbours.

Later history

Christianization

Christianization began in the 9th century and was not complete until the second half of the 12 century. The Christianization of Bulgaria was made official in 864, during the reign of Emperor Boris I during shifting political alliances both with the Byzantine Empire and the kingdom of the East Franks and the communication with the Pope. Because of the Bulgarian Empire's strategic position, the Greek East and the Latin West wanted their people to adhere to their liturgies and to ally with them politically. After overtures from each side, Boris aligned with Constantinople and secured an autocephalous Bulgarian national church in 870, the first for the Slavs. In 918/919, the Bulgarian Patriarchate became the fifth autocephalous Eastern Orthodox patriarchate, after the patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. That status was officially recognised by the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 927.[145] The Bulgarian Empire developed into the cultural and literary centre of Slavic Europe. The development of the Cyrillic script at the Preslav Literary School, which was declared official in Bulgaria in 893, was also declared the official liturgy in Old Church Slavonic, also called Old Bulgarian.[146][147][148]

Although there is some evidence of early Christianization of the East Slavs, Kievan Rus' either remained largely pagan or relapsed into paganism before the baptism of Vladimir the Great in the 980s. The Christianization of Poland began with the Catholic baptism of King Mieszko I in 966. Slavic paganism persisted into the 12th century in Pomerania, which began to be Christianized after the creation of the Duchy of Pomerania as part of the Holy Roman Empire in 1121. The process was mostly completed by the Wendish Crusade in 1147. The final stronghold of Slavic paganism was the Rani, with a temple to their god Svetovid on Cape Arkona, which was taken in a campaign by Valdemar I of Denmark in 1168.

Mediaeval states

After Christianisation, the Slavs established a number of kingdoms, or feudal principalities, which persisted throughout the High Middle Ages. The First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 681 as an alliance between the ruling Bulgars and the numerous Slavs in Lower Moesia. Not long after the Slavic incursion, Scythia Minor was once again invaded, this time by the Bulgars, under Khan Asparukh.[149] Their horde was a remnant of Old Great Bulgaria, an extinct tribal confederacy that was north of the Black Sea in what is now Ukraine. Asparukh attacked Byzantine territories in Eastern Moesia and conquered its Slavic tribes in 680.[150] A peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 681 and marked the foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire. The minority Bulgars formed a close-knit ruling caste.[151] The South Slavs consolidated also the Grand Principality of Serbia. The Kingdom of Croatia was established between the Kupa, the Una and Adriatic Seas, without Istria and major Dalmatian coastal centers. Banate of Bosnia emerged from the 10th century by merging localities called župas, which were remnants of Early Christianity ecclesiastical divisions.[152][153] Duklja similarly started emerging in the south.[154] The West Slavs were distributed in Samo's Empire, which was the first Slavic state to form in the west, followed by the Great Moravia and, after its decline, the Kingdom of Poland, the Obotritic confederation (now eastern Germany) the Principality of Nitra (modern Slovakia) a vassal of the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Duchy of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). After the 1054 death of Yaroslav the Wise and the breakup of Kievan Rus', the East Slavs fragmented into a number of principalities from which Muscovy would emerge after 1300 as the most powerful one. The western principalities of the former Kievan Rus' were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Slavic studies

The debate between proponents of autochthonism and allochthonism began in 1745, when Johann Christoph de Jordan published De Originibus Slavicis. The 19th-century Slovak philologist and poet Pavel Jozef Šafárik, whose theory was founded on Jordanes' Getica, has influenced generations of scholars. Jordanes equated the Sclavenes, the Antes and the Venethi (or Venedi) based on earlier sources such as Pliny the Elder, Tacitus and Ptolemy. Šafárik's legacy was his vision of a Slavic history and the use of linguistics for its study.[155] The Polish scholar Tadeusz Wojciechowski (1839–1919) was the first to use place names to study Slavic history and was followed by A. L. Pogodin and the botanist J. Rostafinski. The first scholar to introduce archaeological data into the discourse on the early Slavs, Lubor Niederle (1865–1944), endorsed Rostafinski's theory in his multi-volume Antiquities of the Slavs. Vykentyi V. Khvoika (1850–1914), a Ukrainian archaeologist of Czech origin, linked the Slavs with the Neolithic Cucuteni culture. A. A. Spicyn (1858–1931) attributed finds of silver and bronze in central and southern Ukraine to the Antes. Czech archaeologist Ivan Borkovsky (1897–1976) postulated the existence of a Slavic "Prague type" of pottery. Boris Rybakov has linked Spicyn's "Antian antiquities" with Chernyakhov culture remains excavated by Khvoika and theorised that the former should be attributed to the Slavs.[155] The debate became politically charged during the 19th century, particularly in connection with the partitions of Poland and the German Drang nach Osten, and the question of whether Germanic or Slavic peoples were indigenous east of the Oder was used to pursue both German and Polish claims to the region.

Some modern scholars debate the meaning and the usage of the term "Slav" depending on the context in which it is used. The word can refer to a culture (or cultures) living north of the River Danube, east of the River Elbe, and west of the River Vistula during the 530s CE.[156] "Slav" is also an identifier for the ethnic group shared by the cultures[157] and denotes any language with linguistic ties to the modern Slavic language family, which may have no connection to either a common culture or a shared ethnicity.[158] Despite the concepts of "Slav", such scholars argue that it is unclear whether any of the descriptions add to an accurate representation of the group's history. Historians such as George Vernadsky, Florin Curta and Michael Karpovich have questioned how, why and to what degree, the Slavs were a cohesive society between the 6th and the 9th centuries.[155][159] The Austrian historian Walter Pohl wrote, "Apparently ethnicity operated on at least two levels: the 'common Slavic' identity, and the identity of single Slavic groups, tribes, or peoples of different sizes that gradually developed, very often taking their name from the territory they lived in. These regional ethnogeneses inspired by Slavic tradition incorporated considerable remnants of Roman and Germanic population ready enough to give up ethnic identities that had lost their cohesion".[100]

See also

- Slavs

- Lech, Čech, and Rus

- List of ancient Slavic peoples and tribes

References

Citations

- Barford 2001, p. vii, Preface.

- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. p. 39.

[...] Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 523.

[...] In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations.

- Atkinson, Dorothy; Dallin, Alexander; Warshofsky Lapidus, Gail, eds. (1977). Women in Russia. Stanford University Press. p. 3.

[...] Ancient accounts link the Amazons with the Scythians and the Sarmatians, who successively dominated the Pontic steppe for a millennium extending back to the seventh century B.C. The descendants of these peoples were absorbed by the Slavs who came to be known as Russians.

- Slovene Studies. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

[...] For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- Geary 2003, p. 144: [B]etween the sixth and seventh centuries, large parts of Europe came to be controlled by Slavs, a process less understood and documented than that of the Germanic ethnogenesis in the west. Yet the effects of Slavicization were far more profound

- "Slav | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- Frank A. Kmietowicz (1976). Ancient Slavs. Worzalla Publishing Company.

Jordanes left no doubt that the Antes were of Slavic origin, when he wrote: 'ab unastirpe exorti, tria nomina ediderunt, id est Veneti, Antes, Sclaveni' (although they derive from one nation, now they are known under three names, the Veneti , Antes and Sclaveni). The Veneti were the West Slavs, the Antes the East Slavs and the Sclaveni, the South or Balkan Slavs.

- "Procopius, History of the Wars, VII. 14. 22–30".

- Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics. MIT Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-262-53267-9.

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past. Central European University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-9639116429.

- Brather, Sebastian (2004). "The Archaeology of the Northwestern Slavs (Seventh To Ninth Centuries)". East Central Europe. 31 (1): 78–81. doi:10.1163/187633004x00116.

- Barford 2001, p. 37.

- Kobyliński 2005, pp. 525–526.

- Kobyliński 2005, p. 526.

- Barford 2001, p. 332.

- F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, pp. 2–3.

- Goffart 2006, p. 95.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 78.

- Peter Heather (17 December 2010). Empires and Barbarians: Migration, Development and the Birth of Europe. Pan Macmillan. pp. 389–396. ISBN 978-0-330-54021-6.

- Wstęp. W: Gerard Labuda: Słowiańszczyna starożytna i wczesnośredniowieczna. Poznań: WPTPN, 2003, s. 16. ISBN 8370633811

- Trubačev, O. N. 1985. Linguistics and Ethnogenesis of the Slavs: The Ancient Slavs as Evidenced by Etymology and Onomastics. Journal of Indo-European Studies (JIES), 13: 203–256.

- Rebała K, Mikulich A, Tsybovsky I, Siváková D, Dzupinková Z, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Szczerkowska Z. "Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the Middle Dnieper Basin". Journal of Human Genetics 52(5):406-14 · February 2007

- Mallory & Adams 1997.

- Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 19.

- Schenker 2008, pp. 61–62.

- Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 22.

- F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, p. 4.

- Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 109.

- Schenker 2008, p. 109.

- Schenker 2008, p. 113.

- cf. Novotná & Blažek:2007 with references. "Classical glottochronology" conducted by Czech Slavist M. Čejka in 1974 dates the Balto-Slavic split to 910±340 BC, Sergei Starostin in 1994 dates it to the 1210s BC and "recalibrated glottochronology" conducted by Novotná & Blažek dates it to 1400–1340 BC. That agrees well with Trziniec-Komarov culture, localised from Silesia to Central Ukraine, which is dated to 1500–1200 BC.

- Mallory 1994, p. 80.

- Mallory 1994, pp. 82–83.

- Barford 2001, p. 14.

- Mallory 1994, p. 78.

- Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 111–112.

- The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Number 1-2 (original from the University of California) Vol. 21 Journal of Indo-European Studies, 1993, digitalized in 2007. p 180

- Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 110.

- Curta 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Kortlandt 1990, p. 133.

- Curta 2001, pp. 71–73.

- Barford 2001, p. 6.

- Curta 2001, pp. 39–40.

- Curta 2001, pp. 40–43.

- Curta 2001, p. 41.

- Barford 2001, pp. 35–35.

- Curta 2001, p. 7.

- Kobyliński 2005, p. 527.

- "Nec minor opinione Eningia. Quidam haec habitari ad Vistulam a Sarmatis, Venedis, Sciris, Hirris, tradunt". Plinius, IV. 27.

- Barford 2001, pp. 6–7.

- Curta 2001, pp. 36–37.

- Barford 2001, p. 7.

- Curta 2001, p. 37.

- Kobyliński 2005, p. 524.

- Barford 2001, p. 36.

- Grimm, Jacob (1853). Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. S. Hirzel. p. 226.

jacob grimm suevi slawen.

- Metzner, Ernst Erich (2011-12-31). "Textgestützte Nachträge zu Namen und Abkunft der 'Böhmer' und 'Mährer' und der zweierlei 'Baiern' des frühen Mittelalters – Die sprachliche, politische und religiöse Grenzerfahrung und Brückenfunktion alteuropäischer Gesellschaften nördlich und südlich der Donau". In Fiala-Fürst, Ingeborg; Czmero, Jaromír (eds.). Amici amico III: Festschrift für Ludvík E. Václavek. Beiträge zur deutschmährischen Literatur (in German). 17. Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci. pp. 321, 347. ISBN 9788024427041.

- Curta 2001, pp. 51–52.

- Curta 2001, p. 51.

- Curta 2001, p. 56.

- Curta 2001, pp. 46, 60.

- Curta 2001, p. 60.

- Barford 2001, p. 29.

- Barford 2001, p. 79.

- Curta 2001, p. 118.

- Curta 2001, pp. 73, 118.

- Curta 2001, pp. 118–119, 347.

- Barford 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Kobyliński 2005, p. 528.

- Barford 2001, chapters 2–4.

- Todd 1995, p. 27.

- Barford 2001, p. 40.

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 104.

- Curta 2001, p. 284.

- Kobyliński 2005, p. 529.

- Todd 1995, p. 26.

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 637.

- New Cambridge Medieval History, pg. 529

- Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (2000). "The Slavs". In Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (ed.). The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe. Sedentary Civilization vs. 'Barbarian' and Nomad. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 138. ISBN 0-312-21207-0.

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 524.

- Gimbutas 1971, p. 42.

- Green 1996, p. 3: Many pre-historians argue it is spurious to identify Iron Age Europeans as Celts (or other such labels).

- Adams, Douglas Q. (January 1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Curta 2001, pp. 6–7, 11.

- Curta 2001, p. 11.

- Magocsi 1996, p. 36.

- Gimbutas 1971, p. .

- Villen, p. 582.

- From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms: Archaeologists and Migrations, p. 264

- Russian Identities. A Historical Survey. N. V. Riasonovsky. Pg 10. Oxford University Press, quoting Johanna Nichols.

- Dolukhanov 2013, p. 167.

- Barford 2001, p. 46.

- Curta 2004, p. 133.

- Curta 2004, p. 148: It is possible that the expansion of the Avar khanate during the second half of the eighth century coincided with the spread of ... Slavic into the neighbouring areas of Bohemia, Moravia and southern Poland, (but) could hardly explain the spread of Slavic into Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, all regions that produced so far almost no archaeological evidence of Avar influence."

- Renfrew 1987, p. .

- Barford 2001, p. 43: An indirect piece of evidence might be the Slavic word strava, which was used to describe Attila’s funerary feast". Priscus noted that communities with a language and customs distinct from Gothic, Hun or Latin existed in the Hun confederacy. They drank medos and could sail in boats crafted from hollowed-out trees (monoxyla).

- Curta 2001, p. 309.

- Geary 2003, p. 145: The question of origin is probably as meaningless for the Slavs as for other barbarian peoples

- Pohl 1998, p. 20.

- Barford 2001, p. 59: citing Procopius

- Dolukhanov, Pavel (2013). The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. New York: Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-582-23618-9.

- Barford 2001, pp. 89–90.

- Barford 2001, p. 128.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict Under Louis the German, 817–876. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-0-8014-3890-5.

- Curta 2001, p. 276.

- Curta 2001, p. 283.

- Curta 2001, pp. 297–307.

- Curta 2001, pp. 44, 332, 333.

- Fouracre, Paul; McKitterick, Rosamond; Reuter, Timothy; Abulafia, David; Luscombe, David Edward; Allmand, C. T.; Riley-Smith, Jonathan; Jones, Michael (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, C.500-c.700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521362917.

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West : 550–1150. The Institute of History. p. 58. ISBN 9788675585732.

- Riha, Thomas; Division, University of Chicago College Syllabus (1963). Readings for Introduction to Russian civilization. Syllabus Division, University of Chicago Press. p. 370.

- Curta 2001, pp. 71, 320, 321.

- Barford 2001, p. 129.

- Barford 2001, p. 124.

- "Folk-Lore, Volume 1".

- Alla Alcenko. "THE MORAL VALUES". East Slavic Paganism.

- Histories. VII. 4, II

- Procopius. Wars V.27, 1–3

- Curta 2001, p. 143.

- Cross 1946, pp. 77–78.

- Dvornik 1956, p. .

- Zguta, Russell (1974). "The Pagan Priests of Early Russia: Some New Insights". Slavic Review. 33 (2): . doi:10.2307/2495793. JSTOR 2495793.

- Dvornik 1956, p. 47.

- Cross 1946, pp. 83–87.

- Andreyev, Nikolay (1962). "Pagan and Christian Elements in Old Russia". Slavic Review. 21 (1): 17. doi:10.2307/3000540. JSTOR 3000540.

- Barford 2001, p. 189.

- Cross 1946, pp. 78–87.

- Barford 2001, p. 193.

- Dvornik 1956, p. 48.

- Cross 1946, p. 82.

- Barford 2001, p. 209.

- Barford 2001, pp. 189–191.

- Dvornik 1956, pp. 48–51.

- Barford 2001, p. 194.

- Leeper, Allen (1933). "Germans, Avars and Slavs". Slavonic and East European Review. 12 (34): 125.

- Cross 1946, p. 79.

- Barford 2001, pp. 195–198.

- Cross 1946, p. 84.

- Barford 2001, p. 198.

- Cross 1946, p. 83.

- Andreyev 1962, p. 18.

- Zguta 1974, p. 263.

- Curta 2001, p. 200.

- Kiminas 2009, p. 15.

- Dvornik 1956, p. 179: The Psalter and the Book of Prophets were adapted or "modernized" with special regard to their use in Bulgarian churches, and it was in this school that glagolitic writing was replaced by the so-called Cyrillic writing, which was more akin to the Greek uncial, simplified matters considerably and is still used by the Orthodox Slavs

- Florin Curta (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

Cyrillic preslav.

- J. M. Hussey, Andrew Louth (2010). "The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire". Oxford History of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-161488-0.

- Zlatarski, Vasil (1938). История на Първото българско Царство. I. Епоха на хуно–българското надмощие (679–852) [History of the First Bulgarian Empire. Period of Hunnic-Bulgarian domination (679–852)] (in Bulgarian). Marin Drinov Publishing House. p. 188. ISBN 978-9544302986. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "Bulgar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Fine, John V.A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0472081493.

- Hadžijahić, Muhamed (2004). Povijest Bosne u IX i X stoljeću (in Bosnian). Preporod (from original and previously unpublished script written in 1986). p. 11. ISBN 9789958820274. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Fine, John V. A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0472082605. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Fine, John V. A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. pp. 2, 58. ISBN 978-0472082605. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Curta 2001, p. .

- Curta 2001, pp. 335–337.

- Curta 2001, pp. 6–35.

- Paul M. Barford, 2004. Identity And Material Culture Did The Early Slavs Follow The Rules Or Did They Make Up Their Own? East Central Europe 31, no. 1:102–103

- Pots, Slavs and 'Imagined Communities': Slavic Archaeologies And The History of The Early Slavs. European Journal of Archaeology 4, no. 3:367–384; George Verdansky and Michael Karpovich, Ancient Russia, vol. 1 of History of Russia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1943

Sources

- Barford, Paul M (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3977-3.

- Cohen, Abner (1974). Two-dimensional Man: An Essay on the Anthropology of Power and Symbolism in Complex Society. University of California Press.

- Cross, S.H. (1946). "Primitive Civilization of the Eastern Slavs". American Slavic and Eastern European Review. 5 (1/2): 51–87. doi:10.2307/2491581. JSTOR 2491581.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic Lingua Franca. Linguistic Notes of an Archaeologist Turned Historian" (PDF). East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est. 31 (1): 125–148. doi:10.1163/187633004x00134. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.

- Dvornik, Francis (1956). The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization. Boston: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. OCLC 459280624.

- Geary, Patrick (2003). Myth of Nations. The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-691-11481-1.

- Gimbutas, Marija Alseikaitė (1971). The Slavs. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-02072-2.

- Pohl, Walter (2003). "A Non-Roman Empire in Central Europe: the Avars". In Goetz, H.W.; Jarnut, Jörg; Pohl, Walter (eds.). Regna and gentes: the relationship between late antique and early medieval peoples and kingdoms in the transformation of the Roman world. BRILL. pp. 571–595. ISBN 978-90-04-12524-7.

- Goffart, Walter (2006). "Does the Distant Past Impinge on the Invasion Age Germans?". In Noble, Thomas F. X. (ed.). From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms. pp. 91–109. ISBN 978-0-415-32741-1.

- Green, Miranda (1996). The Celtic world. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14627-2.

- Heather, Peter (2006). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515954-7.

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate: A History of Its Metropolitanates with Annotated Hierarch Catalogs. Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 978-1434458766.

- Kmietowicz, Frank A. (1976). Ancient Slavs. Worzalla Publishing Company.

- Kobyliński, Zbigniew (2005). "The Slavs". In Fouracre, Paul (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 1: c.500–c.700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–546. ISBN 978-0-521-36291-7.

- Kortlandt, Frederick (1990). "The spread of the Indo-Europeans" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 18: 131–140.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7820-9.

- Mallory, James P. (1994). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7.

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Paliga, Sorin (2014). "A New Synthesis on the Slavic Glotto-and Ethnogenesis and on the Earliest Slavic-Romanian Relations in the 6th century CE". Romanoslavica. 49 (4). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.4537.4563.

- Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology and language: the puzzle of Indo-European origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-521-38675-6.

- Richards, Ronald O. (2003). The Pannonian Slavic Dialect of the Common Slavic Proto-language: The View from Old Hungarian. Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 9780974265308.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1.

- Pohl, Walter (1998). "Conceptions of ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies". In Rosenwein, Barbara; Little, Lester K. (eds.). Debating the Middle Ages: issues and readings. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 15–24. ISBN 978-1-57718-008-1.

- Schenker, Alexander M. (2008). "Proto-Slavonic". In Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville G. (eds.). The Slavonic Languages. Routledge. pp. 60–121. ISBN 978-0-415-28078-5.

- Sussex, Roland; Cubberley, Paul (2011). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29448-5.

- Todd, Malcolm (1995). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19904-7.

- Wolfram, Herwig (2006). "Origo et Religio: Ethnic traditions and literature in early medieval texts". In Noble, Thomas F. X. (ed.). From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms. pp. 57–74. ISBN 978-0-415-32741-1.

Further reading

- Nowakowski, Wojciech; Bartkiewicz, Katarzyna. "Baltes et proto-Slaves dans l'Antiquité. Textes et archéologie". In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne, vol. 16, n°1, 1990. pp. 359-402. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/dha.1990.1472];[www.persee.fr/doc/dha_0755-7256_1990_num_16_1_1472]