Getae

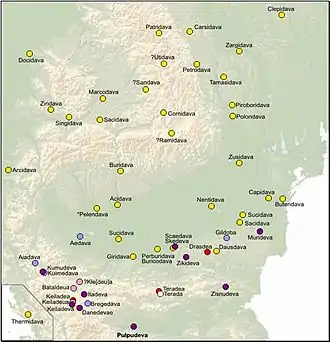

The Getae (/ˈdʒiːtiː, ˈɡiːtiː/ JEE-tee, GHEE-tee) or Gets (/dʒɛts, ɡɛts/ JETS, GHETS; Ancient Greek: Γέται, singular Γέτης) were several Thracian[1] tribes that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form Get and plural Getae may be derived from a Greek exonym: the area was the hinterland of Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast, bringing the Getae into contact with the ancient Greeks from an early date. Although it is believed that the Getae were related to their westward neighbours, the Dacians, several scholars, especially in the Romanian historiography, posit that the Getae and the Dacians were the same people.

Ethnonym

The ethnonym Getae was first used by Herodotus. The root was also used for the Tyragetae, Thyssagetae, Massagetae, and others.

Getae and Dacians

Ancient sources

Strabo, one of the first ancient sources to mention Getae and Dacians, stated in his Geographica (c. 7 BC – 20 AD) that the Dacians lived in the western parts of Dacia, "towards Germania and the sources of the Danube", while the Getae lived in the eastern parts, towards the Black Sea, both south and north of the Danube.[2] The ancient geographer also wrote that the Dacians and Getae spoke the same language,[3] after stating the same about Getae and Thracians.[4]

Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia (Natural History), c. 77–79 AD, stated something similar: "... though various races have occupied the adjacent shores; at one spot the Getae, by the Romans called Daci".[5]

Appian, who began writing his Roman History under Antoninus Pius, Roman Emperor from 138 to 161, noted: "[B]ut going beyond these rivers in places they rule some of the Celts over the Rhine and the Getae over the Danube, whom they call Dacians".[6][7]

Justin, the 3rd century AD Latin historian, wrote in his Epitome of Pompeius Trogus that Dacians are spoken of as descendants of the Getae: "Daci quoque suboles Getarum sunt" (The Dacians as well are a scion of the Getae).[8][9]

In his Roman History (c. 200 AD), Cassius Dio added: "I call the people Dacians, the name used by the natives themselves as well as by the Romans, though I am not ignorant that some Greek writers refer to them as Getae, whether that is the right term or not...".[10][11] He also said the Dacians lived on both sides of the Lower Danube; the ones south of the river (today's northern Bulgaria), in Moesia, were called Moesians, while the ones north of the river were called Dacians. He argued that the Dacians are "Getae or Thracians of Dacian race":[12]

In ancient times, it is true, Moesians and Getae occupied all the land between Haemus and the Ister; but as time went on some of them changed their names, and since then there have been included under the name of Moesia all the tribes living above Dalmatia, Macedonia, and Thrace, and separated from Pannonia by the Savus, a tributary of the Ister. Two of the many tribes found among them are those formerly called the Triballi, and the Dardani, who still retain their old name.[13]

Modern interpretations

There is a dispute among scholars about the relations between the Getae and Dacians, and this dispute also covers the interpretation of ancient sources. Some historians such as Ronald Arthur Crossland state that even Ancient Greeks used the two designations "interchangeable or with some confusion". Thus, it is generally considered that the two groups were related to a certain degree,[14] the exact relation is a matter of controversy.

Same people

Strabo, as well as other ancient sources, led some modern historians to consider that, if the Thracian ethnic group should be divided, one of this divisions should be the "Daco-Getae".[15] The linguist Ivan Duridanov also identified a "Dacian linguistic area"[16] in Dacia, Scythia Minor, Lower Moesia, and Upper Moesia.

Romanian scholars generally went further with the identification, historian Constantin C. Giurescu claiming the two were identical.[17] The archaeologist Mircea Babeș spoke of a "veritable ethno-cultural unity" between the Getae and the Dacians. According to Glanville Price, the account of the Greek geographer Strabo shows that the Getae and the Dacians were one and the same people.[18] Others who support the identity between Getae and Dacians with ancient sources include freelance writer James Minahan and Catherine B Avery, who claim the people whom the Greek called Getae were called Daci by the Romans.[19] [20] This same belief is stated by some British historians such as David Sandler Berkowitz and Philip Matyszak.[21][22] The Bulgarian historian and thracologist Alexander Fol considers that the Getae became known as "Dacians" in Greek and Latin in the writings of Caesar, Strabo and Pliny the Elder, as Roman observers adopted the name of the Dacian tribe to refer to all the unconquered inhabitants north of the Danube.[23] Also, Edward Bunbury believed the name of Getae, by which they were originally known to the Greeks on the Euxine, was always retained by the latter in common usage: while that of Dacians, whatever be its origin, was that by which the more western tribes, adjoining the Pannonians, first became known to the Romans.[24] Some scholars consider the Getae and Dacians to be the same people at different stages of their history and discuss their culture as Geto-Dacian.[25]

Same language, distinct people

Historian and archaeologist Alexandru Vulpe found a remarkable uniformity of the Geto-Dacian culture,[26] however he is one of the few Romanian archaeologists to make a clear distinction between the Getae and Dacians, arguing against the traditional position of the Romanian historiography that considered the two people the same.[27] Nevertheless, he chose to use the term "Geto-Dacians" as a conventional concept for the Thracian tribes inhabiting the future territory of Romania, not necessarily meaning an "absolute ethnic, linguistic or historical unity".[27]

Ronald Arthur Crossland suggested the two designations may refer to two groups of a "linguistically homogeneous people" that had come to historical prominence at two distinct periods of time. He also compared the probable linguistic situation with the relation between modern Norwegian and Danish languages.[28] Paul Lachlan MacKendrick considered the two as "branches" of the same tribe, speaking two dialects of a common language.[29]

The Romanian historian of ideas and historiographer Lucian Boia stated: "At a certain point, the phrase Geto-Dacian was coined in the Romanian historiography to suggest a unity of Getae and Dacians".[30] Lucian Boia took a sceptical position, arguing the ancient writers distinguished among the two people, treating them as two distinct groups of the Thracian ethnos.[30][31] Boia contended that it would be naive to assume Strabo knew the Thracian dialects so well,[30] alleging that Strabo had "no competence in the field of Thracian dialects".[31] The latter claim is contested, some studies attesting Strabo's reliability and sources.[32] There is no reason to disregard Strabo's belief that the Daci and the Getae spoke the same language.[18] Boia also stressed that some Romanian authors cited Strabo indiscriminately.[31]

A similar position was adopted by Romanian historian and archaeologist G. A. Niculescu, who also criticized the Romanian historiography and the archaeological interpretation, particularly on the "Geto-Dacian" culture.[33] In his opinion, Alexandru Vulpe saw ancient people as modern nations, leading the latter to interpret the common language as a sign of a common people, despite Strabo making a distinction between the two.[27]

History

7th – 4th century BC

From the 7th century BC onwards, the Getae came into economic and cultural contact with the Greeks, who were establishing colonies on the western side of Pontus Euxinus, nowadays the Black Sea. The Getae are mentioned for the first time together in Herodotus in his narrative of the Scythian campaign of Darius I in 513 BC, during which the latter conquered the Getae.[34] According to Herodotus, the Getae differed from other Thracian tribes in their religion, centered around the god (daimon) Zalmoxis whom some of the Getae called Gebeleizis.[35]

Between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC, the Getae were mostly under the rule of the flourishing Odrysian kingdom. During this time, the Getae provided military services and became famous for their cavalry. After the disintegration of the Odrysian kingdom, smaller Getic principalities began to consolidate themselves.

Prosperity

Before setting out on his Persian expedition, Alexander the Great defeated the Getae and razed one of their settlements.[36] In 313 BC, the Getae formed an alliance with Callatis, Odessos, and other western Pontic Greek colonies against Lysimachus, who held a fortress at Tirizis (modern Kaliakra).[37]

The Getae flourished especially in the first half of the 3rd century BC. By about 200 BC, the authority of the Getic prince, Zalmodegicus, stretched as far as Histria, as a contemporary inscription shows.[38] Other strong princes included Zoltes and Rhemaxos (about 180 BC). Also, several Getic rulers minted their own coins. The ancient authors Strabo[39] and Cassius Dio[40] say that Getae practiced ruler cult, and this is confirmed by archaeological remains.

Conflict with Rome

In 72–71 BC Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus became the first Roman commander to march against the Getae. This was done to strike at the western Pontic allies of Mithridates VI, but he had limited success. A decade later, a coalition of Scythians, Getae, Bastarnae and Greek colonists defeated C. Antonius Hybrida at Histria.[41][42] This victory over the Romans allowed Burebista, the leader of this coalition, to dominate the region for a short period (60–50 BC).

In the mid-first century BC Burebista organized a kingdom consisting of descendants of those whom the Greeks had called Getae, as well as Dacians, or Daci, the name applied to people of the region by the Romans.[25]

Augustus aimed at subjugating the entire Balkan peninsula, and used an incursion of the Bastarnae across the Danube as a pretext to devastate the Getae and Thracians. He put Marcus Licinius Crassus in charge of the plan. In 29 BC, Crassus defeated the Bastarnae with the help of the Getic prince Rholes.[43] Crassus promised him help for his support against the Getic ruler Dapyx.[44] After Crassus had reached as far the Danube Delta, Rholes was appointed king and returned to Rome. In 16 BC, the Sarmatae invaded the Getic territory and were driven back by Roman troops.[45] The Getae were placed under the control of the Roman vassal king in Thrace, Rhoemetalces I. In 6 AD, the province of Moesia was founded, incorporating the Getae south of the Danube River. The Getae north of the Danube continued tribal autonomy outside the Roman Empire.

Culture

According to Herodotus, the Getae were "the noblest as well as the most just of all the Thracian tribes".[46] When the Persians, led by Darius the Great, campaigned against the Scythians, the Thracian tribes in the Balkans surrendered to Darius on his way to Scythia, and only the Getae offered resistance.[46]

One episode from the history of the Getae is attested by several ancient writers.[47][48]

When Lysimachus tried to subdue the Getae he was defeated by them. The Getae king, Dromichaetes, took him prisoner but he treated him well and convinced Lysimachus there is more to gain as an ally than as an enemy of the Getae and released him. According to Diodorus, Dromichaetes entertained Lysimachus at his palace at Helis, where food was served on gold and silver plates. The discovery of the celebrated tomb at Sveshtari (1982) suggests that Helis was located perhaps in its vicinity,[49] where remains of a large antique city are found along with dozens of other Thracian mound tombs.

As stated earlier, just like the Dacians, the principal god of the Getae was Zalmoxis whom they sometimes called Gebeleizis.

This same people, when it lightens and thunders, aim their arrows at the sky, uttering threats against the god; and they do not believe that there is any god but their own.

— Herodotus. Histories, 4.94.

Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia mentions a tribe called the Tyragetae,[50] apparently a Daco-Thracian tribe who dwelt by the river Tyras (the Dniester). Their tribal name appears to be a combination of Tyras and Getae; see also the names Thyssagetae and Massagetae.

The Roman poet Ovid, during his long exile in Tomis, is asserted to have written poetry (now lost) in the Getic language. In his Epistulae ex Ponto, written from the northern coast of the Black Sea, he asserts that two major, distinct languages were spoken by the sundry tribes of Scythia, which he referred to as Getic, and Sarmatian.

Physical appearance

Jerome (Letter CVII to Laeta. II) described the Getae as red and yellow-haired.[51]

Fringe views on alternative origins

Suggested link to Goths

The Getae are sometimes confused with the Goths in works of early medieval authors.[52][53][54][55][56] This confusion is notably expanded on in works of Jordanes, himself of Gothic background, who transferred earlier historical narratives about the Getae to the Goths.[57] At the close of the 4th century AD, Claudian, court poet to the emperor Honorius and the patrician Stilicho, uses the ethnonym Getae to refer to the Visigoths.

During 5th and 6th centuries, several historians and ethnographers (Marcellinus Comes, Orosius, John Lydus, Isidore of Seville, Procopius of Caesarea) used the same ethnonym Getae to name populations invading the Eastern Roman Empire (Goths, Gepids, Kutrigurs, Slavs). For instance, in the third book of the History of the Wars Procopius details: "There were many Gothic nations in earlier times, just as also at the present, but the greatest and most important of all are the Goths, Vandals, Visigoths, and Gepaedes. In ancient times, however, they were named Sauromatae and Melanchlaeni; and there were some too who called these nations Getic."[58] The Getae were considered the same people as the Goths by Jordanes in his Getica written at the middle of the 6th century. He also claims that at one point the "Getae" migrated out of Scandza, while identifying their deity Zalmoxis as a Gothic king. Jordanes assumed the earlier testimony of Orosius. The 9th-century work De Universo of Rabanus Maurus states, "The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae.[59]

Suggested link to Jats

There have long been attempts to link the Getae and Massagetae to the Jats of South Asia. Likewise, the Dacians have been linked to the Dahae of Central Asia (and the Dahae to the Dasas of South Asia).W. W. Hunter claimed in 1886, suggested that the Jats were an Iranian people – most likely Scythian/Saka in origin,[60] Alexander Cunningham (1888) believed that references in classical European sources – like Strabo, Ptolemy and Pliny – to peoples such as the Zaths, may have been the Getae and/or Jats.[61][62] More recent authors, like Tadeusz Sulimirski,[63] Weer Rajendra Rishi,[64] and Chandra Chakraberty,[65][66] have also linked the Getae and Jats.

Less credible, however, are parallel claims by Alexander Cunningham that the Xanthii (or Zanthi) and Iatioi – mentioned by Strabo, Ptolemy and Pliny – may have been synonymous with the Getae and/or Jats.[61] The Xanthii were later established to be a subgroup (tribe or clan) of the Dahae. Subsequent scholars, such as Edwin Pulleyblank, Josef Markwart (also known as Joseph Marquart) and László Torday, suggest that Iatioi may be another name for a people known in classical Chinese sources as the Yuezhi and in South Asian contexts as the Kuṣānas (or Kushans).[62]

Notes

- "Getae". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

Getae, an ancient people of Thracian origin, inhabiting the banks of the lower Danube region and nearby plains

- Strabo & 20 AD, VII 3,13.

- Strabo & 20 AD, VII 3,14.

- The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 3) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1982. ISBN 1108007147.

- Pliny the Elder & 77 AD, IV 25.

- Appian & 160 AD, Praef. 1.4.

- Millar, Fergus; Cotton, Hannah M.; Rogers, Guy M. (2004). Rome, the Greek World, and the East, Volume 2: Government, Society, and Culture in the Roman Empire page 189. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5520-1.

- Justin & 3rd century AD, XXXII 3.

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in Pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci, & Moesians, translated by Mary Stansfield-Popovic page 335. John Benjamins North America. ISBN 978-90-256-0793-7.

- Shelley, William Scott (199). The Origins of the Europeans: Classical Observations in Culture and Personality, page 108, Cassius Dio (LXVII.4). Intl Scholars Pubns. ISBN 1-57309-220-7.

- Sidebottom 2007, p. 6.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 55.22.6-55.22.7. "The Suebi, to be exact, dwell beyond the Rhine (though many people elsewhere claim their name), and the Dacians on both sides of the Ister; those of the latter, however, who live on this side of the river near the country of the Triballi are reckoned in with the district of Moesia and are called Moesians, except by those living in the immediate neighbourhood, while those on the other side are called Dacians and are either a branch of the Getae are Thracians belonging to the Dacian race that once inhabited Rhodope."

- Cassius Dio LI 27

- The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 10) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1996. J. J. Wilkes mentions "the Getae of the Dobrudja, who were akin to the Dacians"; (p. 562)

- András Mócsy (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia. Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7714-9. See p. 364, n. 41: "If there is any justification for dividing the Thracian ethnic group, then, unlike V. Georgiev who suggests splitting it into the Thraco-Getae and the Daco-Mysi, I consider a division into the Thraco-Mysi and the Daco-Getae the more likely."

- Duridanov, Ivan. "The Thracian, Dacian and Paeonian languages". Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- Giurescu, Constantin C. (1973). Formarea poporului român (in Romanian). Craiova. p. 23. "They (Dacians and Getae) are two names for the same people [...] divided in a large number of tribes". See also the hypothesis of a Daco-Moesian language / dialectal area supported by linguists like Vladimir Georgiev, Ivan Duridanov and Sorin Olteanu.

- Price, Glanville (2000). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22039-9., p. 120

- Minahan 2000, p. 549.

- Avery 1962, p. 497.

- Sandler Berkowitz & Morison 1984, p. 160.

- Matyszak 2009, p. 215.

- Fol 1996, p. 223.

- Bunbury 1979, p. 151.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 335.

- Petrescu-Dîmbovița, Mircea; Vulpe, Alexandru, eds. (2001). Istoria Românilor, vol. I (in Romanian). Bucharest.

- Niculescu, Gheorghe Alexandru (2007). "Archaeology and Nationalism in The History of the Romanians". In Kohl, Philip; Kozelsky, Mara; Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (eds.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-0-226-45059-9. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 3) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1982. ISBN 1-108-00714-7. In chapter "20c Linguistic problems of the Balkan area", at page 838, Ronald Arthur Crossland argues "it may be the distinction made by Greeks and Romans between the Getae and Daci, for example, reflected the importance of different sections of a linguistically homogenous people at different times". He furthermore recalls Strabo's testimony and Georgiev's hypothesis for a 'Thraco-Dacian' language.

- Paul Lachlan MacKendrick (1975). The Dacian Stones Speak. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4939-1. "The natives with whom we shall be concerned in this chapter are the Getae of Muntenia and Moldavia in the eastern steppes, and the Dacians of the Carpathian Mountains. Herodotus calls them 'the bravest and the justest of the Thracians,' and they were in fact two branches of the same tribe, speaking two dialects of the same Indo-European language." (p. 45)

- Boia, Lucian (2004). Romania: Borderland of Europe. Reaktion Books. p. 43. ISBN 1-86189-103-2.

- Boia, Lucian (2001). History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. p. 14. ISBN 963-9116-97-1.

- Janakieva, Svetlana (2002). "La notion de ΟΜΟΓΛΩΤΤΟΙ chez Strabon et la situation ethno-linguistique sur les territoires thraces". Études Balkaniques (in French) (4): 75–79. The author concluded Strabo's claim sums an experience following of many centuries of neighbourhood and cultural interferences between the Greeks and the Thracian tribes

- Niculescu, Gheorghe Alexandru (2004–2005). "Archaeology, Nationalism and "The History of the Romanians" (2001)". Dacia, Revue d'Archéologie et d'Histoire Ancienne (48–49): 99–124. He dedicates a large part of his assessment to the archaeology of "Geto-Dacians" and he concludes that with few exceptions "the archaeological interpretations [...] are following G. Kossinna’s concepts of culture, archaeology and ethnicity".

- The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10 - Persia, Greece, and the Western Mediterranean Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0521228046 p 494

- Herodotus. Histories, 4.93–4.97.

- Arrian. Anabasis, Book IA. "The Getae did not sustain even the first charge of the cavalry; for Alexander’s audacity seemed incredible to them, in having thus easily crossed the Ister, the largest of rivers, in a single night, without throwing a bridge over the stream. Terrible to them also was the closely locked order of the phalanx, and violent the charge of the cavalry. At first they fled for refuge into their city, which was distant about a parasang from the Ister; but when they saw that Alexander was leading his phalanx carefully along the side of the river, to prevent his infantry being anywhere surrounded by the Getae lying in ambush, but that he was sending his cavalry straight on, they again abandoned the city, because it was badly fortified."

- Strabo. Geography, 7.6.1. "On this coast-line is Cape Tirizis, a stronghold, which Lysimachus once used as a treasury."

- Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 18.288

- Strabo. Geography, 16.2.38–16.2.39.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 68.9.

- Livy. Ab urbe condita, 103.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 38.10.1–38.10.3.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 52.24.7; 26.1.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 51.26.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 54.20.1–54.20.3.

- Herodotus. Histories, 4.93.

- Strabo. Geography, 3.8.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.9.5.

- Delev, P. (2000). "Lysimachus, the Getae, and Archaeology (2000)". The Classical Quarterly. New Series. 50 (2): 384–401. doi:10.1093/cq/50.2.384.

- Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia, 4.26. "Leaving Taphræ, and going along the mainland, we find in the interior the Auchetæ, in whose country the Hypanis has its rise, as also the Neurœ, in whose district the Borysthenes has its source, the Geloni, the Thyssagetæ, the Budini, the Basilidæ, and the Agathyrsi with their azure-coloured hair."

- The Letters of St. Jerome

- Theodor Mommsen (2005). A History of Rome Under the Emperors. New York: Routledge. p. 281. "The Getae were Thracians, the Goths Germans, and apart from the coincidental similarity in their names they had nothing whatever in common."

- David Punter (2015). A New Companion to The Gothic. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 31.

- Robert W. Rix (2014). The Barbarian North in Medieval Imagination: Ethnicity, Legend, and Literature. New York: Routledge. p. 33.

- Harold W. Attridge (1992). Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. p. 696.

- Irmeli Valtonen (2008). The North in the Old English Orosius: A Geographical Narrative in Context. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique. p. 110.

- Shami Ghosh (2015). Writing the Barbarian Past: Studies in Early Medieval Historical Narrative. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 49–50.

- Procopius. History of the Wars, Book III (Wikisource).

- Maurus, Rabanus (1864). Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.). De universo. Paris.

The Massagetae are in origin from the tribe of the Scythians, and are called Massagetae, as if heavy, that is, strong Getae.

- W. W. Hunter, 2013, The Indian Empire: Its People, History and Products, Routledge, 2013, p. 251.

- Alexander Cunningham, 1888, cited by: Sundeep S. Jhutti, 2003, The Getes, Philadelphia, PA; Department of East Asian languages & Civilizations University of Pennsylvania, p. 13.

- Sundeep S. Jhutti, 2003, "The Getes", Sino-Platonic Papers, no. 127 (October), pp. 15–17. (Access: 18 March 2016).

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians: Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan ("great" Jat) tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

- Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- Chakraberty, Chandra (1948). The prehistory of India: tribal migrations. Vijayakrishna Bros. p. 35.

- Chakraberty, Chandra (1997). Racial basis of Indian culture: including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. Aryan Books International. ISBN 8173051100.

References

Ancient

- Appian (c. 160 AD). Historia Romana [Roman History] (in Ancient Greek). Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Justin (c. 3rd century AD). Trogi pompei historiarum philippicarvm epitoma [Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus] (in Latin). Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Pliny the Elder (77–79 AD). Naturalis Historia [Natural History] (in Latin). Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Strabo (c. 20 AD). Geographica (in Ancient Greek). Check date values in:

|year=(help)

Modern

- Avery, Catherine B. (1962). The New Century classical handbook. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1979). A history of ancient geography among the Greeks and Romans: from the earliest ages till the fall of the Roman empire. London: Humanities Press International, Incorporated. ISBN 978-90-70265-11-3.

- Fol, Alexander (1996). "Thracians, Celts, Illyrians and Dacians". History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. edited by Unesco. Bernan Assoc; illustrated edition. ISBN 978-92-3-102812-0.

- Millar, Fergus; Cotton, Hannah M.; Rogers, Guy M. (2004). Rome, the Greek World, and the East, Volume 2: Government, Society, and Culture in the Roman Empire. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5520-1.

- Matyszak, Philip (2009). The Enemies Of Rome. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28772-9.

- Minahan, James B. (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313309847.

- Sandler Berkowitz, David; Morison, Richard (1984). Humanist Scholarship and Public Order: Two Tracts Against the Pilgrimage of Grace. Associated Univ Pr. ISBN 978-0918016010.

- Sidebottom, Harry (2007). "International Relations". The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare: Volume 2, Rome from the Late Republic to the Late Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78274-6.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-8160-4964-6.

External links

Media related to Dacia and Dacians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dacia and Dacians at Wikimedia Commons