Giorgione

Giorgione (UK: /ˌdʒɔːrdʒiˈoʊneɪ, -ni/, US: /ˌdʒɔːrˈdʒoʊni/, Italian: [dʒorˈdʒoːne]; born Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco; c. 1477/78–1510)[2][3]was an Italian painter of the Venetian school during the High Renaissance from Venice, who died in his thirties. Giorgione is known for the elusive poetic quality of his work, though only about six surviving paintings are firmly attributed to him. The uncertainty surrounding the identity and meaning of his work has made Giorgione one of the most mysterious figures in European art.

Giorgione | |

|---|---|

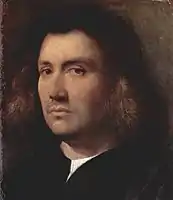

A possible self-portrait, perhaps as David | |

| Born | Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco 1470s |

| Died | 1510 (aged 30–36) Venice, Republic of Venice (present day Veneto, Italy) |

| Nationality | Italian[1] |

| Education | Giovanni Bellini |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | The Tempest Sleeping Venus Castelfranco Madonna The Three Philosophers |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

Together with Titian, who was probably slightly younger, he founded the distinctive Venetian school of Italian Renaissance painting, which achieves much of its effect through colour and mood, and is traditionally contrasted with Florentine painting, which relies on a more linear disegno-led style.

Life

What little is known of Giorgione's life is given in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. The painter came from the small town of Castelfranco Veneto, 40 km inland from Venice. His name sometimes appears as Zorzo. The variant Giorgione (or Zorzon) may be translated "Big George". It is unclear how early in boyhood he went to Venice, but stylistic evidence supports the statement of Carlo Ridolfi that he served his apprenticeship there under Giovanni Bellini; there he settled and rose to prominence as a master.[4][5]

Contemporary documents record that his gifts were recognized early. In 1500, when he was only twenty-three (if Vasari is correct about his age when he died), he was chosen to paint portraits of the Doge Agostino Barbarigo and the condottiere Consalvo Ferrante. In 1504, he was commissioned to paint an altarpiece in memory of another condottiere, Matteo Costanzo, in the cathedral of his native town, Castelfranco. In 1507, he received, at the order of the Council of Ten, partial payment for a picture (subject unknown) in which he was engaged for the Hall of the Audience in the Doge's Palace. From 1507 to 1508 he was employed, with other artists of his generation, to decorate with frescoes the exterior of the newly rebuilt Fondaco dei Tedeschi (or German Merchants' Hall) at Venice, having already done similar work on the exterior of the Casa Soranzo, the Casa Grimani alli Servi and other Venetian palaces. Very little of this work now survives.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Vasari mentions an important event in Giorgione's life, and one which influenced his work, his meeting with Leonardo da Vinci on the occasion of the Tuscan master's visit to Venice in 1500. All accounts agree in representing Giorgione as a person of distinguished and romantic charm, a great lover and a musician, given to express in his art the sensuous and imaginative grace, touched with poetic melancholy, of the Venetian existence of his time. They represent him further as having made in Venetian painting an advance analogous to that made in Tuscan painting by Leonardo more than twenty years before; that is, as having released the art from the last shackles of archaic rigidity and placed it in possession of full freedom and the full mastery of its means.

He was very closely associated with Titian; while Vasari says Giorgione was Titian's master, Ridolfi says that they both were pupils of Giovanni Bellini, and lived in his house. They worked together on the Fondaco dei Tedeschi frescoes, and Titian finished at least some paintings of Giorgione after his death, although which ones remains very controversial.

Giorgione also introduced a new range of subjects. Besides altarpieces and portraits he painted pictures that told no story, whether biblical or classical, or if they professed to tell a story, neglected the action and simply embodied in form and color moods of lyrical or romantic feeling, much as a musician might embody them in sounds. Innovating with the courage and felicity of genius, he had for a time an overwhelming influence on his contemporaries and immediate successors in the Venetian school, including Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, Palma il Vecchio, il Cariani, Giulio Campagnola (and his brother), and even on his already eminent master, Giovanni Bellini. In the Venetian mainland, Giorgionismo strongly influenced Morto da Feltre, Domenico Capriolo, and Domenico Mancini.

Giorgione died of the plague then raging, on the 17th of September, 1510.[6] He was usually thought to have died and been buried on the island of Poveglia in the Venetian lagoon,[7][8][9][10][11] but an archival document published for the first time in 2011 places his death on the island of Lazzareto Nuovo; both were used as places of quarantine in times of plague.[12] October 1510 is also the date of a letter by Isabella d'Este to a Venetian friend; asking him to buy a painting by Giorgione; the letter shows she was aware he was already dead. Significantly, the reply a month later said the painting was not to be had at any price.

His name and work continue to exercise a spell on posterity. But to identify and define, among the relics of his age and school, precisely what that work is, and to distinguish it from the similar work of other men whom his influence inspired, is a very difficult matter. Though there are no longer any supporters of the "Pan Giorgionismus"[13] which a century ago claimed for Giorgione nearly every painting of the time that at all resembles his manner, there are still, as then, exclusive critics who reduce to half a dozen the list of extant pictures which they will admit to be actually by this painter.

Works

For his home town of Castelfranco, Giorgione painted the Castelfranco Madonna, an altarpiece in sacra conversazione form—Madonna enthroned, with saints on either side forming an equilateral triangle. This gave the landscape background an importance which marks an innovation in Venetian art, and was quickly followed by his master Giovanni Bellini and others.[14] Giorgione began to use the very refined chiaroscuro called sfumato—the delicate use of shades of color to depict light and perspective—around the same time as Leonardo. Whether Vasari is correct in saying he learned it from Leonardo's works is unclear—he is always keen to ascribe all advances to Florentine sources. Leonardo's delicate color modulations result from the tiny disconnected spots of paint that he probably derived from Illuminated manuscript techniques and first brought into oil painting. These gave Giorgione's works the magical glow of light for which they are celebrated.

Most central and typical of all of Giorgione's extant works is the Sleeping Venus now in Dresden. It was first recognized by Giovanni Morelli, and is now universally accepted, as being the same as the picture seen by Marcantonio Michiel and later by Ridolfi (his 17th century biographer) in the Casa Marcello at Venice. An exquisitely pure and severe rhythm of line and contour chastens the sensuous richness of the painting. The sweep of white drapery on which the goddess lies; and the glowing landscape that fills the space behind her; most harmoniously frame her divinity. The use of an external landscape to frame a nude is innovative; but in addition, to add to her mystery, she is shrouded in sleep, spirited away from accessibility to any conscious expression.

It is recorded by Michiel that Giorgione left this piece unfinished and that the landscape, with a Cupid which subsequent restoration has removed, were completed after his death by Titian. The picture is the prototype of Titian's own Venus of Urbino and of many more by other painters of the school; but none of them attained the fame of the first exemplar. The same concept of idealized beauty is evoked in a virginally pensive Judith from the Hermitage Museum, a large painting which exhibits Giorgione's special qualities of color richness and landscape romance, while demonstrating that life and death are each other's companions rather than foes.

Apart from the altarpiece and the frescoes, all Giorgione's surviving works are small paintings designed for the wealthy Venetian collector to keep in his home; most are under two feet (60 cm) in either dimension. This market had been emerging over the last half of the 15th century in Italy, and was much better established in the Netherlands, but Giorgione was the first major Italian painter to concentrate his work on it to such an extent—indeed soon after his death the size of paintings began to increase with the prosperity and palaces of the patrons.

The Tempest has been called the first landscape in the history of Western painting. The subject of this painting is unclear, but its artistic mastery is apparent. The Tempest portrays a soldier and a breast-feeding woman on either side of a stream, amid a city's rubble and an incoming storm. The multitude of symbols in The Tempest offer many interpretations, but none is wholly satisfying. Theories that the painting is about duality (city and country, male and female) have been dismissed since radiography has shown that in the earlier stages of the painting the soldier to the left was a seated female nude.[15]

The Three Philosophers is equally enigmatic and its attribution to Giorgione is still disputed. The three figures stand near a dark empty cave. Sometimes interpreted as symbols of Plato's cave or the Three Magi, they seem lost in a typical Giorgionesque dreamy mood, reinforced by a hazy light characteristic of his other landscapes, such as the Pastoral Concert, now in the Louvre. The latter "reveals the Venetians' love of textures", because the painter "renders almost palpable the appearance of flesh, fabric, wood, stone, and foliage".[16] The painting is devoid of harsh contours and its treatment of landscape has been frequently compared to pastoral poetry, hence the title.

Giorgione and the young Titian revolutionized the genre of the portrait as well. It is exceedingly difficult and sometimes simply impossible to differentiate Titian's early works from those of Giorgione. None of Giorgione's paintings are signed and only one bears a reliable date:[17] his portrait of Laura (1 June 1506), one of the first to be painted in the "modern manner", distinguished by dignity, clarity, and sophisticated characterization. Even more striking is the Portrait of a Young Man now in Berlin, acclaimed by art historians for "the indescribably subtle expression of serenity and the immobile features, added to the chiseled effect of the silhouette and modeling".[16]

Few of the portraits attributed to Giorgione appear as straightforward records of the appearance of a commissioning individual, although it is entirely possible that many are. Many can be read as types designed to express a mood or atmosphere, and certainly many of the examples of the portrait tradition Giorgione initiated appear to have had this purpose, and not to have been sold to the sitter. The subjects of his non-religious figure paintings are equally hard to discern. Perhaps the first question to ask is whether there was intended to be a specific meaning to these paintings that ingenious research can hope to recover. Many art historians argue that there is not: "The best evidence, perhaps, that Giorgione's pictures were not particularly esoteric in their meaning is provided by the fact that while his stylistic innovations were widely adopted, the distinguishing feature of virtually all Venetian non-religious painting in the first half of the 16th century is the lack of learned or literary content".[18]

Attributions

Attributions of work by Giorgione's hand dates from soon after his death, when some of his paintings were completed by other artists, and his considerable reputation also led to very early erroneous claims of attribution. The vast bulk of documentation for paintings in this period relates to large commissions for Church or government; the small domestic panels that make up the bulk of Giorgione's oeuvre are always far less likely to be recorded. Other artists continued to work in his style for some years, and probably by the mid-century deliberately deceptive work had started.[19]

Primary documentation for attributions comes from the Venetian collector Marcantonio Michiel. In notes dating from 1525 to 1543 he identifies twelve paintings and one drawing as by Giorgione, of which five of the paintings are identified virtually unanimously with surviving works by art historians:[20] The Tempest, The Three Philosophers, Sleeping Venus, Boy with an Arrow,[21] and Shepherd with a Flute (not all accept the last as by Giorgione however). Michiel describes the Philosophers as having been completed by Sebastiano del Piombo, and the Venus as finished by Titian (it is now generally agreed that Titian did the landscape). Some recent art historians also involve Titian in the Three Philosophers. The Tempest is therefore the only one of the group universally accepted as wholly by Giorgione. In addition, the Castelfranco Altarpiece in his hometown has rarely, if ever, been doubted, nor have the wrecked fresco fragments from the German warehouse. The Vienna Laura is the only work with his name and the date (1506). This is on the back and is not necessarily by his own hand, but does appear to come from the period. The early pair of paintings in the Uffizi are usually accepted.

After that, things become more complicated, as exemplified by Vasari. In the first edition of the Vite (1550), he attributed a Christ Carrying the Cross to Giorgione; in the second edition completed in 1568 he ascribed authorship, variously, to Giorgione in his biography, which was printed in 1565, and to Titian in his, printed in 1567. He had visited Venice in between these dates, and may have obtained different information.[23] The uncertainty in distinguishing between the painting of Giorgione and the young Titian is most apparent in the case of the Louvre's Pastoral Concert (or Fête champêtre), described in 2003 as "perhaps the most contentious problem of attribution in the whole of Italian Renaissance art,"[24] but affects a large number of paintings possibly from Giorgione's last years.

The Pastoral Concert is one of a small group of paintings, including the Virgin and Child with Saint Anthony and Saint Roch in the Prado,[25] which are very close in style and, according to Charles Hope, have been "more and more frequently given to Titian, not so much because of any very compelling resemblance to his undisputed early works—which would surely have been noted before—as because he seemed a less implausible candidate than Giorgione. But no one has been able to create a coherent sequence of Titian's early works that includes these ones, in a way that commands general support, and fits the known facts of his career. An alternative proposal is to assign the Pastoral Concert and the other pictures like it to a third artist, the very obscure Domenico Mancini."[26] While Crowe and Cavalcaselle considered the Concert from Palazzo Pitti as Giorgione's masterpiece but disattributed the Louvre's Pastoral Concert, Lermolieff reinstated the Pastoral Concert and claimed instead that the Pitti Concert was by Titian.[27]

Giulio Campagnola, well known as the engraver who translated the Giorgionesque style into prints, but none of whose paintings are securely identified, is also sometimes also brought into consideration. For example, the late W.R. Rearick gave him Il Tramonto (see Gallery) and he is an alternative choice for a number of drawings that might be by Titian or Giorgione, and both are sometimes credited with the design of some of his engravings.[28]

At an earlier period in Giorgione's short career, a group of paintings is sometimes described as the "Allendale group", after the Allendale Nativity (or Allendale Adoration of the Shepherds, rather more correctly) in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This group includes another Washington painting, the Holy Family, and an Adoration of the Magi predella panel in the National Gallery, London.[29] This group, now often expanded to include a very similar Adoration of the Shepherds in Vienna,[30] and sometimes further, are usually included (increasingly) or excluded together from Giorgione's oeuvre. Ironically, the Allendale Nativity caused the rupture in the 1930s between Lord Duveen, who sold it to Samuel Kress as a Giorgione, and his expert Bernard Berenson, who insisted it was an early Titian. Berenson had played a significant part in reducing the Giorgione catalogue, recognising fewer than twenty paintings.[31]

Matters are further complicated because no drawing can be certainly identified as by Giorgione (although one in Rotterdam is widely accepted), and a number of aspects of the arguments over the defining of Giorgione's late style involve drawings.

Despite being greatly praised by all contemporary writers, and remaining a great name in Italy, Giorgione became less known to the wider world, and many of his (probable) paintings were assigned to others. The Hermitage Judith for example, was long regarded as a Raphael, and the Dresden Venus a Titian. In the late 19th century a great Giorgione revival began, and the fashion ran the other way. Despite well over a century of dispute, controversy remains active. Large numbers of pictures attributed to Giorgione a century ago, in particular portraits, are now firmly excluded from his oeuvre, but debate is, if anything, more fierce now than then.[32] There are effectively two fronts on which the battles are fought: paintings with figures and landscape, and portraits. According to David Rosand in 1997, "The situation has been thrown into new critical confusion by Alessandro Ballarin's radical revision of the corpus ... [Paris exhibition catalogue, 1993, increasing it] ... as well as Mauro Lucco ... [Milan book, 1996]."[33] Recent major exhibitions at Vienna and Venice in 2004 and Washington in 2006, have given art historians further opportunities to see disputed works side by side (see External links below).

But the situation remains confused; in 2012 Charles Hope complained: "In fact, there are only three paintings known today for which there is clear and credible early evidence that they were by him. Despite this, he is now generally credited with between twenty and forty paintings. But most of these ... bear no resemblance to the three just mentioned. Some of them might be by Giorgione, but in most cases there is no way of telling".[34]

Legacy

Though he died at the age of 32 or 33, Giorgione left a lasting legacy to be developed by Titian and 17th-century artists. Giorgione never subordinated line and colour to architecture, nor an artistic effect to a sentimental presentation. He was arguably the first Italian to paint landscapes with figures as movable pictures in their own frames with no devotional, allegorical, or historical purpose—and the first whose colours possessed that ardent, glowing, and melting intensity which was so soon to typify the work of all the Venetian School.

Selected works

- The Test of Fire of Moses (1500–1501) - Oil on panel, 89 x 72, Uffizi, Florence

- The Judgement of Solomon (1500–1501) - Oil on panel, 89 x 72 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- Judith (c. 1504) - Oil on canvas, transferred from panel, 144 x 66,5 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1505–10) - Oil on panel, 90.8 x 110.5 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Castelfranco Madonna (Madonna and Child Enthroned between St. Francis and St. Nicasius); c. 1505 - Oil on wood, 200 x 152 cm, Duomo, Castelfranco Veneto

- Portrait of a Young Bride (Laura) (c. 1506) Oil on wood, 41 x 33,5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- The Tempest (La Zingara e il Soldato) (La Zingarella e il Soldato) (c. 1508) - Oil on canvas, 82 x 73 cm, Accademia, Venice

- La Vecchia (Old Woman) (c. 1508) - Oil on canvas, 68 x 59 cm, Accademia, Venice

- Pastoral Concert (c. 1509) widely now given to Titian- Oil on canvas, 110 x 138 cm, Louvre, Paris

- Portrait of a Youth (1508–10) - Oil on canvas, 72,5 x 54 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- The Three Philosophers (1509) - Oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Portrait of Warrior with his Equerry (c. 1509) - Oil on canvas, 90 x 73 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

- Sleeping Venus (c. 1510) - Oil on canvas, 108,5 x 175 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- The Impassioned Singer (c. 1510) - Oil on canvas, 102 x 78 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Portrait of a Young Man - Wood, 69,4 x 53,5 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Young Man with Arrow (Garçon à la flèche) (Knabe mit Pfeil ) ( L'enfant à la flèche) (sometimes attributed)

Gallery

One of the "Allendale group", the small Adoration of the Magi predella, London

One of the "Allendale group", the small Adoration of the Magi predella, London Young Man with Arrow, (1506?) Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Young Man with Arrow, (1506?) Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Judith, Hermitage Museum.

Judith, Hermitage Museum. La Vecchia, "The Old Woman", Accademia. "Col tempo", or "With age" reads the paper.

La Vecchia, "The Old Woman", Accademia. "Col tempo", or "With age" reads the paper. Il Tramonto, London. Little known until the middle of the 20th century, and still a controversial attribution.

Il Tramonto, London. Little known until the middle of the 20th century, and still a controversial attribution. The Berlin Giustiniani Portrait (or Portrait of a Man), one of the most frequently attributed portraits

The Berlin Giustiniani Portrait (or Portrait of a Man), one of the most frequently attributed portraits The San Diego Portrait of a Man, another of the more frequently attributed portraits

The San Diego Portrait of a Man, another of the more frequently attributed portraits The Budapest Portrait of a Young Man, damaged.

The Budapest Portrait of a Young Man, damaged. Portrait of a Venetian Gentleman, by Giorgione and Titian 1510 – National Gallery of Art

Portrait of a Venetian Gentleman, by Giorgione and Titian 1510 – National Gallery of Art Portrait of a Young Man, attributed to Giorgione

Portrait of a Young Man, attributed to Giorgione

Notes

- Giorgione at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Gould, 102–3. Vasari's 1st edition had the former, his 2nd the latter. There is no documentary evidence, and Vasari gets his date of death, which is known, wrong by a year.

- ″Some recent discoveries supply a little more information about Giorgione′s short life.... Giorgione was born at some point between 18 September 1473 and 17 September 1474, a few years earlier than had previous been thought.″ Tom Nichols, Giorgione's Ambiguity (Reaktion Books, 2020, pp. 19-20).

- Vasari, Giorgio; Conaway Bondanella, Julia; Bondanella, Peter (1991). The Lives of the Artists. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953719-8.; In 2017 at the University of Sydney Library, a librarian discovered an original Giorgione sketch that included a definitive date and cause of death for the artist, with an ink inscription that reads "1510 Ihs Maria. On the day of 17 September, Giorgione of Castelfranco, a very excellent artist died of the plague in Venice at the age of 36 and he rests in peace" "Dante's Divine Comedy with Giorgione illustration and death notice". University of Sydney Library. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- Slattery, Luke (16 February 2019). "Divine discovery: Renaissance art found by Sydney University librarian". The Australian. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- University of Sydney Library. "Dante's Divine Comedy with Giorgione illustration and death notice". Digital Collections. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Herbert Frederick Cook (1904). Giorgione.

- Archivio veneto. 1894.

- Romney Fra Angelico, Watteau Raphael's Frescos (1903). Masters in Arts. p. 446.

- Tobias, Michael (1995). A Vision of Nature. Kent State University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-87338-483-4.

- Press release, 2011, The Burlington Magazine; Three-Pipe problem Archived 2014-05-03 at the Wayback Machine; Il Giornale d'Arte (in Italian)

- An old art historians' jibe at Richter, George Martin (1 January 1932). "A Clue to Giorgione's Late Style". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 60 (348): 123–132. JSTOR 865045.

- Teresa Pignati in Jane Martineau (ed.), The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, pp. 29–30, 1983, Royal Academy of Arts, London.

- "The Tempest". Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- "2006 Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- Brown, D. A., Ferino Pagden, S., Anderson, J., & Berrie, B. H. (2006). Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting. Washington: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-300-11677-2 p. 42

- Charles Hope in Jane Martineau (ed.), The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, 1983, p. 35, Royal Academy of Arts, London

- Cecil Gould, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London 1975, p. 107, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- "EB online". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2009-07-02. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- Vienna, illustrated below. Described in 2007 as "a rare example of a painting still universally attributed to Giorgione" in Lucy Whitaker, Martin Clayton, The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection; Renaissance and Baroque, p. 185, Royal Collection Publications, 2007, ISBN 978-1-902163-29-1.

- From the Louvre Museum Official Website It is often called the Fête Champêtre (meaning "Picnic") in older works.

- Charles Hope in David Jaffé (ed.), Titian, The National Gallery Company/Yale, p. 12, London 2003, ISBN 1-85709-903-6

- Charles Hope in David Jaffé (ed.), Titian, The National Gallery Company/Yale, p. 14, London 2003 ISBN 1-85709-903-6

- Listed as "Giorgione (?)" in the 1996 Prado catalogue, which notes the debate, but in 2007 labelled as Titian in the gallery. See Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 129, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, No ISBN.

- Hope in Jaffé (ed.), Titian, 2003, op. cit., p. 14. Francis Richardson, who wrote the catalogue entry for the Prado painting (no. 34) in: Jane Martineau (ed.), The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, 1983, Royal Academy of Arts, London, after considering Mancini, is one of those happy to attribute the painting to Titian. The Mancini suggestion comes originally from a German article of 1933 by J. Wilde: 'Die Probleme um Domenico Mancini', JKSW

- Uglow, Luke (2014). "Giovanni Morelli and his friend Giorgione: connoisseurship, science and irony". Journal of Art Historiography. 11.

- John Dixon Hunt (ed.), The Pastoral Landscape, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1992, pp. 146–7, ISBN 0-89468-181-8

- NGA 2006 exhibition brochure, page 4 Archived October 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Kunthistoriches Museum 2004 exhibition website Archived March 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "his works...not a score in all" in Italian Painters of the Renaissance, 1952, (many editions). By the last (1957) edition of his Lists, Berenson had changed his mind and listed all the three main "Allendale" works as "by Giorgione" – see Gould op. cit. p. 105.

- See the Art Journal review of a major 1993 Paris exhibition, which lists some Ballarin additions to the corpus by Wendy Stedman Sheard

- David Rosand, Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice, 2nd edn. 1997, p. 186, n. 74; Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-56568-5 For some Ballarin attributions, see previous note.

- Hope, Charles (24 May 2012). "At the National Gallery". London Review of Books. 34 (10): 22. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giorgione". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–33.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giorgione". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–33.- Gould, Cecil, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- Encyclopedia of Artists, volume 2, edited by William H.T. Vaughan, ISBN 0-19-521572-9, 2000

Further reading

- David Alan Brown and Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Bellini·Giorgione·Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006 (accompanying an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).

- The Complete Paintings of Giorgione. Introduction by Cecil Gould. Notes by Pietro Zampetti. NY: Harry N. Abrams. 1968.

- Giorgione. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studio per il quinto centenario della nascita (Castelfranco Veneto 1978), Castelfranco Veneto, 1979.

- Tom Nichols, Giorgione's Ambiguity, London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2020.

- Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, Giorgione: Mythos und Enigma, Ausst. Kat. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Wien, 2004 (translated as Giorgione: Myth and Enigma, Milan, Italy: Skira, 2004).

- Sylvia Ferino-Pagden (Hg.), Giorgione entmythisiert, Turnhout, Brepols, 2008.

- Unglaub, Jonathan, "The Concert Champêtre: The Crises of History and the Limits of Pastoral." Arion, Vol. 5, no. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1997): 46–96.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giorgione. |

- Giorgione at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Video: "Giorgione and the problem of attribution", by Charles Hope, London Review of Books, 2016

- Tour: Giorgione and the High Renaissance in Venice, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- Giorgione featured on 10 Euro Coin

- Giorgione death notice and original sketch at the University of Sydney Library