Giuseppe Mazzuoli (1644–1725)

Giuseppe Mazzuoli (1644 Volterra – 1725 Rome) was an Italian sculptor working in Rome in the Bernini-derived Baroque style. He produced many highly accomplished sculptures of up to monumental scale but was never a leading figure in the Roman art world.

Life

Mazzuoli was born in Volterra and trained in Siena but spent his most of his adult working life in Rome.[1] There, he entered the workshop of Ercole Ferrata[2] where he became the only pupil of Melchiorre Cafà who also worked with Ferrata.[3] Like Ferrata, Mazzuoli was frequently drawn on by Gian Lorenzo Bernini[4] to assist with large commissions. He was among the co-workers who cooperated in Bernini's Tomb of Pope Alexander VII (1672–78).

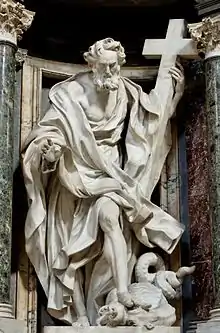

When late in 1702 Pope Clement XI and Benedetto Cardinal Pamphili announced their grand scheme for twelve over life-size sculptures of the Apostles to fill the niches along the nave of the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, the project was divided among all the premier sculptors of Rome.[5] Each statue was to be sponsored by an illustrious prince, and Mazzuoli was assigned the statue of Saint Philip, financed by the archbishop of Würzburg and finished in 1711.[6] Like most sculptors,[7] Mazzuolli was provided with a sketch by Clement's favourite painter, Carlo Maratta, which he was to follow.[8] Robert Cahn observed "When Saint Philip is compared with other apostles in the series, it is clear that the somewhat old-fashioned, Berniniesque style manifested in Mazzuoli's single assignment was losing appeal."[9]

Mazzuoli carried out some major commissions for the Order of Malta, most noticeably the main altar of St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta, finished in 1703. There, he created a marble group of the Baptism of Christ which might on the one hand have been influenced by Cafà's undocumented and abandoned designs from 1666,[10] and it is certainly strongly dependent on a small baptism group by Alessandro Algardi.[11] In the same church, he produced in his later years allegorical figures for the tomb of Ramon Perellos y Roccaful (died 1720), Grand Master of the Order of Malta.[12]

His brother, Annibale Mazzuoli, was a painter. His son, also a sculptor, is generally distinguished as 'Giuseppe Mazzuoli the younger.

Selected works, in approximate chronological order

- Charity, 1673–75, for Bernini's tomb of Alexander VII, carried out under the direct supervision of Bernini.[13]

- Bust of Cardinal Giulio Gabrielli the Elder, 1675–1676, in the Museo di Roma at Palazzo Braschi in Rome.

- Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist, 1677–79, in situ flanking the high altar at the Church of Gesù e Maria, Corso, Rome. The church and the altar were designed by Carlo Rainaldi,[14] who is likely to have provided sketches for the sculptures that form part of the altar he designed.

- Portrait busts of Fausto Cardinal Poli and Mons. Gaudenzio Poli, c. 1680, in situ in the Sacristy designed by Bernini (1641) of the Church of San Crisogono, Rome.[15]

- Clemency, c. 1684 an allegorical figure among the sculptures for the tomb of Clement X Altieri, St. Peter's Basilica, executed under the design direction of Mattia De Rossi (1684).[16]

- Bust of Innocent XII, 1700, in situ in a niche in the apse of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Rome.

- Baptism of Christ, 1700–1703, Valletta, main altar of St. John's Co-Cathedral.

- Bust of Clement XI, 1703, also in situ in a niche in the apse of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Rome.[17]

- Saint Philip, finished in 1711, in situ at the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome.[18] A reduced marble version of the sculpture, probably made for the archbishop of Würzburg who financed the Lateran sculpture, is in Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum.[6]

- Nereid, c. 1705–15 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC); it was identified as Thetis when in the Samuel H. Kress collection,[19] and attributed to the "school of Bernini."

- The Death of Adonis, 1709 (Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg).

- Charity Triumphing over Greed, 1710–15 (Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg); a bronze reduction is in the collections of Harvard University Art Museums.[20]

- (attributed to the workshop or circle of Mazzuoli) Paired busts: Diana and Endymion, c. 1710–25 (Detroit Institute of Arts).

- Death of Cleopatra, c. 1713 (Pinacoteca, Siena); a marble version of this group, c. 1723, is in the grounds of the Jardim Botânico Tropical, Lisbon,[21] and a terracotta modello at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[22]

- Immaculate Conception, completed by September 1678, Church of San Martino, Siena. Giuseppe also completed the St Thomas of Villanova in this church.[23]

- Apostles standing on brackets for the piers of the Duomo di Siena (Brompton Oratory, South Kensington, London. The Christ and the Virgin Mary for the same positions were removed and have been lost; they are represented by gilded terracotta modelli (bought from Jacques Heim for the Royal Scottish Museum, 1982).[24]

- Portrait busts in medallions and allegorical figures of the four classical Virtues, dated 1713 and 1714 but executed in 1715–17 and 1718–19 (for the portrait busts),[25] in situ in the two double funerary monuments facing each other in the Rospigliosi-Pallavicini chapel, Church of San Francesco a Ripa, Rome. The architecture of the wall monuments is by Niccolò Michetti. Portrait busts of duke Giovanni Battista and Matia Cammilla Rospigliosi-Pallavicini (Pallavicini collection, Rome) were among the works contracted from Mazzuoli; copies of them were incorporated in the chapel's wall monuments.[26]

- (attributed to Mazzuoli) Pair of Angels above the altar in the second chapel on the left in the Church of Santa Maria in Campitelli. The attribution to Mazzuoli[27] is strengthened by the presence once more of Carlo Rainaldi, who masterpiece is this church.

- Allegorical figures for the Tomb of Ramon Perello (died 1720), in the church of Saint John, Valletta, Malta.

- Charity, 1723 (Chapel in the Palazzo del Monte di Pietà, Rome). Mazzuoli's late work takes its place in a rich program of sculpture in the chapel originally designed by Carlo Maderno, but refitted by Giovanni Antonio De Rossi with rich colored marble revetments.[28] Mazzuoli notes his age— età 79— with his inscribed signature.

- Education of the Virgin.[29]

A number of terracotta models kept by Mazzuoli's heirs in Siena seem to have been part of a cache of the family workshop holdings that was donated to the Isituto di Belli Arti of Siena about 1767 by Giuseppe Maria Mazzuoli.[30]

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giuseppe Mazzuoli. |

- Lione Pascoli, Vite de' Pittori, Scultori ed Architetta Moderni, vol. II (Rome 1736)

- Andrea Bacchi, Stefano Pierguidi, Bernini e gli allievi: Giuliano Finelli, Andrea Bolgi, Francesco Mochi, François Duquesnoy, Ercole Ferrata, Antonio Raggi, Giuseppe Mazzuoli, Firenze [u.a.], E-Ducation.it [u.a.], 2008. – 359 S. : zahlr. Ill. ; 29 cm (I grandi maestri dell'arte ; 24).

- Tomaso Montanari, Pittura e scultura nella Roma di fine Seicento: un busto inedito di Giuseppe Mazzuoli da un dipinto di Jacob Ferdinand Voet, in: Prospettiva, 117/118.2005(2006), p. 183–188.

- Marina Carta, La statua della Carità di Giuseppe Mazzuoli per la Cappella del Monte di Pietà di Roma: alcune precisazioni sulla progettazione e realizzazione, in Sculture romane del Settecento: la professione dello scultore / Fondazione Marco Besso. A cura di Elisa Debenedetti. – Roma, Bonsignori, 2001 -. – (Studi sul Settecento romano ; ...). 2., 2002. – (Studi sul Settecento romano ; 18). – ISBN 88-7597-309-1, p. 41–53.

- Alessandro Angelini, Giuseppe Mazzuoli, la bottega dei fratelli e la committenza della famiglia De' Vecchi, in: Prospettiva, 79.1995, p. 78–100.

- Monika Butzek, Giuseppe Mazzuoli e le statue degli Apostoli del duomo di Siena, in: Prospettiva, 61.1991, p. 75–89.

- Ursula Schlegel, "Some Statuettes of Giuseppe Mazzuoli", in: The Burlington Magazine 109 No. 772 (July) 1967, pp. 386–395.

Notes

- A return trip to Siena 1677–79 is noted by his early biographer Lione Pascoli.

- Filippo Baldinucci, Notizie dei professori del disegno... 18 (Florence) 1773:173.

- Pascoli.

- Among his documented work on Bernini projects can be noted the clay bozzetti and wax models for casting in bronze connected with Bernini's Ciborium, discussed by Jennifer Montagu, "Two Small Bronzes from the Studio of Bernini" The Burlington Magazine 109 No. 775 (October 1967:566–571).

- "The largest sculptural task in Rome during the early eighteenth century," according to Rudolf Wittkower (Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600–1750, rev. ed. 1965:290); "the distribution for commissions is, at the same time, a good yardstick for measuring the reputation of contemporary sculptors."

- cf. Michael Conforti, The Lateran Apostles, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, 1977; Conforti published a short resume of his dissertation: Planning the Lateran Apostles, in: Henry A. Millon (Ed.), Studies in Italian Art and Architecture 15th through 18th Centuries, Rome 1980 (Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 35), pp. 243–260.

- The notable exception being Pierre Le Gros who successfully refused to work to Maratta's design and wasn't given a sketch.

- Robert Cahn, "A Counterproof from a Drawing of the Lateran 'Saint Philip'" Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 38.1 (1979:11–13); Cahn is discussing a counterproof of a chalk drawing made of the finished sculpture as it was insdtalled, doubtless by one of Mazzuoli's numerous workshop assistants.

- Cahn 1979:11.

- Cafà died in 1667 while working on this bronze group.

- cf. *Keith Sciberras, Melchiorre Cafà's Baptism of Christ for the Knights of the Order of Malta, in: Keith Sciberras (Ed.), Melchiorre Cafà. Maltese Genius of the Roman Baroque, Valletta 2006, pp. 97–112.

- A terracotta modello is at the Musée du Louvre, first recognized by Schlegel 1967:393 fig. 10.

- A series of terracotta bozzetti and a bronze statuette in Berlin were associated with Mazzuoli's known figures of Caritas spanning his career, and attributed to him by Ursula Schlegel, "Some Statuettes of Giuseppe Mazzuoli" The Burlington Magazine 109 No. 772 (July 1967:386-95).

- Touring Club Italiano (TCI), Roma e dintorni (1965:181.

- TCI, Roma e dintorni 1965:443.

- TCI, Roma e dintorni 1965:494

- Both busts are noted in TCI, Roma e dintorni 1965:440

- The first attribution to Mazzuoli, noted by Westin 1974:36, is in 1745

- Georges Wildenstein preserved the tradition of the French collector from whom they bought it, that it had come from a royal context in or near Naples

- Illustration, on-line.

- Schlegel 1967:391, note 8

- "New AcquisitionS;: illustration, on-line.

- The work, commissioned by Alessandro de Vacchi, was completed in Rome and sent to Siena (David L. Bershad , "Recent Archival Discoveries concerning Michelangelo's 'Deposition' in the Florence Cathedral and a Hitherto Undocumented Work of Giuseppe Mazzuoli (1644–1725)" The Burlington Magazine 120 No. 901 (April 1978:225–227).

- Note by Richard Verdi in The Burlington Magazine 124 No. 953 (August 1982:518.

- Robert Westin and Jean Westin, "Contributions to the Late Chronology of Giuseppe Mazzuoli" The Burlington Magazine 116 No. 850 (January 1974:36, 39–41) note from archival documents that the chapel was complete and the architectural elements of the wall tombs installed by the inscribed dates; Mazzuoli's payments begin in July 1716 and the last polishing was paid for in November 1717.

- Frederick den Broeder, responding to the Westin article, "Letters", The Burlington Magazine 116 No. 855 (June 1974:332).

- In TCI, Roma e dintorni 1965:254.

- TCI, Roma e dintorni 1965:249.

- Henry Hawley, "Giuseppe Mazzuoli: Education of the Virgin" Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 60 (1973:293-99).

- Noted by Carl Brandon Strehlke in reviewing the exhibition of the Saracini Collection for The Burlington Magazine 132 No. 1042 (January 1990:61 and fig. 63, illustrating a terracotta model of St. John the Baptist in the collection.