Würzburg

Würzburg (UK: /ˈvɜːrtsbɜːrɡ, ˈvʊərts-/, US: /ˈwɜːrts-, ˈwʊərts-/,[2][3][4][5][6][lower-alpha 1] German: [ˈvʏʁtsbʊʁk] (![]() listen); Main-Franconian: Wörtzburch) is a city in the traditional region of Franconia in the north of the German State of Bavaria. At the next-down tier of local government it is the administrative seat of Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main.

listen); Main-Franconian: Wörtzburch) is a city in the traditional region of Franconia in the north of the German State of Bavaria. At the next-down tier of local government it is the administrative seat of Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main.

Würzburg

| |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)   Clockwise from top: Marienberg Fortress and Old Bridge – the Main with a newer bridge – the Old Town with cathedral, narrow square and city hall – the Residence inspired by the Palace of Versailles in Paris | |

Coat of arms | |

Location of Würzburg

| |

Würzburg  Würzburg | |

| Coordinates: 49°47′N 9°56′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Lower Franconia |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Christian Schuchardt (CDU) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 87.63 km2 (33.83 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 177 m (581 ft) |

| Population (2019-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 127,934 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 97070–97084 |

| Dialling codes | 0931 |

| Vehicle registration | WÜ |

Würzburg is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) from Frankfurt am Main, to west and Nuremberg (Nürnberg), to east. The city has around 130,000 residents.[7]

The regional dialect is East Franconian.

The city is outside of the Landkreis Würzburg (district of Würzburg) but has its administrative centre.

History

Early and medieval history

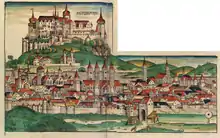

A Bronze Age (Urnfield culture) refuge castle, the Celtic Segodunum,[8] and later a Roman fort, stood on the hill known as the Leistenberg,[9] the site of the present Fortress Marienberg. The former Celtic territory was settled by the Alamanni in the 4th or 5th century, and by the Franks in the 6th to 7th. Würzburg was the seat of a Merovingian duke from about 650. It was Christianized in 686 by Irish missionaries Kilian, Kolonat and Totnan. The city is mentioned in a donation by Duke Hedan II to bishop Willibrord, dated 1 May 704, in castellum Virteburch. The Ravenna Cosmography lists the city as Uburzis at about the same time.[10] The name is presumably of Celtic origin, but based on a folk etymological connection to the German word Würze "herb, spice", the name was Latinized as Herbipolis in the medieval period.[11]

Beginning in 1237, the city seal depicted the cathedral and a portrait of Saint Kilian, with the inscription SIGILLVM CIVITATIS HERBIPOLENSIS. It shows a banner on a tilted lance, formerly in a blue field, with the banner quarterly argent and gules (1532), later or and gules (1550). This coat of arms replaced the older seal of the city, showing Saint Kilian, from 1570.[12]

The first diocese was founded by Saint Boniface in 742 when he appointed the first bishop of Würzburg, Saint Burkhard. The bishops eventually created a secular fiefdom, which extended in the 12th century to Eastern Franconia. The city was the site of several Imperial Diets, including the one of 1180, at which Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony and Bavaria, was banned for three years from the Empire[9] and his duchy Bavaria was handed over to Otto of Wittelsbach. Massacres of Jews took place in 1147 and 1298.

The first church on the site of the present Würzburg Cathedral was built as early as 788 and consecrated that same year by Charlemagne; the current building was constructed from 1040 to 1225 in Romanesque style. The University of Würzburg was founded in 1402 and re-founded in 1582. The citizens of the city revolted several times against the prince-bishop.

In 1397, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia had visited the city and promised its people the status of a free Imperial City. However, the German ruling princes forced him to withdraw these promises. In 1400, the citizenry was decisively defeated by the troops of the bishop in the Battle of Bergtheim, and the city fell under his control permanently until the dissolution of the fiefdom.[13]:41

Modern history

The Würzburg witch trials, which occurred between 1626 and 1631, are one of the largest peace-time mass trials. In Würzburg, under Bishop Philip Adolf an estimated number between 600 and 900 alleged witches were burnt.[14] In 1631, Swedish King Gustaf Adolf invaded the town and plundered the castle.

In 1720, the foundations of the Würzburg Residence were laid. In 1796, the Battle of Würzburg between Habsburg Austria and the First French Republic took place. The city passed to the Electorate of Bavaria in 1803, but two years later, in the course of the Napoleonic Wars, it became the seat of the Electorate of Würzburg (until September 1806), the later Grand Duchy of Würzburg. In 1814, the town became part of the Kingdom of Bavaria and a new bishopric was created seven years later, as the former one had been secularized in 1803 (see also Reichsdeputationshauptschluss).

In 1817, Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer founded Schnellpressenfabrik Koenig & Bauer (the world's first steam-driven printing press manufacturer).

The Hep-Hep riots from August to October 1819 were pogroms against Ashkenazi Jews, beginning in the Kingdom of Bavaria, during the period of Jewish emancipation in the German Confederation. The antisemitic communal violence began on August 2, 1819 in Würzburg and soon reached the outer regions of the German Confederation. Many Jews were killed and much Jewish property was destroyed.

In 1848 Catholic bishops held the Würzburg Bishops' Conference, a forerunner of later German and Austrian conferences. By distinction, the Würzburg Conference is a name given to the meeting of representatives of the smaller German states in 1859 to devise some means of mutual support. The conference, however, had no result. Würzburg was bombarded and taken by the Prussians in 1866, in which year it ceased to be a fortress.[9]

In the early 1930s, around 2,000 Jews had lived in Würzburg, which was also a rabbinic center. During the Kristallnacht, in 1938, many Jewish houses and shops were raided, looted or destroyed.[15] The contents of two synagogues were stolen or destroyed.[15] Many Jews were imprisoned and tortured by the Gestapo.[15] Between November 1941 and June 1943 Jews from the city were sent to the Nazi concentration camps in Eastern Europe.[16]

From April 1943 to March 1945 a subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp was located in the city, with dozens of prisoners, mostly from Poland and the Soviet Union.[17]

On 16 March 1945, about 90% of the city was destroyed in 17 minutes by fire bombing from 225 British Lancaster bombers during a World War II air raid. Würzburg became a target for its role as a traffic hub and to break the spirit of the population.[13]:19

All of the city's churches, cathedrals, and other monuments were heavily damaged or destroyed. The city center, which mostly dated from medieval times, was totally destroyed in a firestorm in which 5,000 people perished.

Over the next 20 years, the buildings of historical importance were painstakingly and accurately reconstructed. The citizens who rebuilt the city immediately after the end of the war were mostly women – Trümmerfrauen ("rubble women") – because the men were either dead or still prisoners of war. On a relative scale, Würzburg was destroyed to a larger extent than was Dresden in a firebombing the previous month.

On 3 April 1945, Würzburg was occupied by the U.S. 12th Armored Division and U.S. 42nd Infantry Division in a series of frontal assaults masked by smokescreens. The battle continued until the final Wehrmacht resistance was defeated on 5 April 1945.[18][19]

The 2016 Würzburg train attack took place at the Würzburg-Heidingsfeld railway station on 18 July.

Geography

Würzburg spans the banks of the river Main in the region of Lower Franconia in the north of the state of Bavaria, Germany. The heart of the town is on the locally eastern (right) bank. The town is enclosed by the Landkreis Würzburg, but is not a part of it.

Würzburg covers an area of 87.6 square-kilometres and lies at an altitude of around 177 metres.[20]

Of the total municipal area, in 2007, building area accounted for 30%, followed by agricultural land (27.9%), forestry/wood (15.5%), green spaces (12.7%), traffic (5.4%), water (1.2%) and others (7.3%).[21]

The centre of Würzburg is surrounded by hills. To the west lies the 266 metre Marienberg and the Nikolausberg (359 m) to the south of it. The Main flows through Würzburg from the south-east to the north-west.

City structure

Würzburg is divided into 13 Stadtbezirke which are additionally structured into 25 boroughs. In the following overview, the boroughs and their numbers are allocated to the 13 municipals.

|

01 Altstadt

|

02 Zellerau

03 Dürrbachtal

04 Grombühl

05 Lindleinsmühle

|

06 Frauenland

07 Sanderau

08 Heidingsfeld

09 Heuchelhof

|

10 Steinbachtal

11 Versbach

12 Lengfeld

13 Rottenbauer

|

Demographics

Würzburg had 128,538 inhabitants as of 31 December 2016.

Foreign population

| Largest groups of foreign residents: | |

| Nationality | Population (31.12.2019) |

|---|---|

| 1,316 | |

| 1,086 | |

| 885 | |

| 803 | |

| 702 | |

| 553 | |

| 526 | |

| 483 | |

| 414 | |

| 375 | |

Religion

Economy

Würzburg is mainly known as an administrative center. Its largest employers are the Julius-Maximilians-University and the municipality. The largest private employers are Brose Fahrzeugteile followed by Koenig & Bauer, a maker of printing machines. Würzburg is also the capital of the German wine region Franconia which is famous for its mineralic dry white wines especially from the Silvaner grape. Würzburger Hofbräu brewery also locally produces a well-known pilsner beer.

Würzburg is home of the oldest Pizzeria in Germany. Nick di Camillo opened his restaurant named Bier- und Speisewirtschaft Capri on 24 March 1952.[24] Mr Camillo received the honor of the Italian Order of Merit.

In 2017, the GDP per inhabitant was €62,229. This places the district 13th out of 96 districts (rural and urban) in Bavaria (overall average: €46,698).[25]

Military

Following World War II, Würzburg was host to the U.S. Army's 1st and 3rd Infantry Divisions as well as an army hospital and various other U.S. military units that maintained a presence in Germany. The last troops were withdrawn from Würzburg in 2008, thus concluding more than 60 years of U.S. presence there.

Arts and culture

Notable artists who lived in Würzburg include poet Walther von der Vogelweide (12th and 13th centuries), philosopher Albertus Magnus and painter Mathias Grünewald. Sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider (1460–1531) served as mayor and participated in the German Peasants' War.

Some of the city's "100 churches" survived intact. In style they range from Romanesque (Würzburg Cathedral), Gothic (Marienkapelle), Renaissance (Neubaukirche), Baroque (Stift Haug Kirche) to modern (St. Andreas).

Major festivals include the Africa Festival in May, the Mozart Festival in June/July and the Kiliani Volksfest in mid-July.

Main sights

.jpg.webp)

- Würzburger Residenz: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the vast compound near the center of the town was commissioned by two prince-bishops, the brothers Johann Philipp Franz and Friedrich Karl von Schönborn. Several architects, including Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt and Maximilian von Welsch, supervised the construction between 1720 and 1744, in imitation of the Palace of Versailles,[9] but it is mainly associated with the name of Balthasar Neumann, the creator of its famous Baroque staircase. The palace suffered severe damage in the British bombing of March 1945, but has been completely rebuilt. The main attractions are:

- Hofkirche: The church interior is richly decorated with paintings, sculptures and stucco ornaments. The altars were painted by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

- Treppenhaus: Here Giovanni Battista Tiepolo created the largest fresco in the world, which adorns the vault over the staircase designed by Balthasar Neumann.

- Kaisersaal: The "Imperial Hall", the centerpiece of the palace, testifies to the close relationship between Würzburg and the Holy Roman Empire.

- Festung Marienberg is a fortress on Marienberg, the hill to the west of the city centre, overlooking the whole town area as well as the surrounding hills. Most current structures date to the Renaissance and Baroque periods, but the foundations of the chapel go back to the 8th century.

- Alte Mainbrücke (Old Main Bridge) was built 1473–1543 to replace the destroyed Romanesque bridge dated from 1133. In two phases, beginning in 1730, the bridge was adorned with twelve 4.5 meter statues of saints and historically important figures like John of Nepomuk, Mary and Saint Joseph, Charlemagne and Pepin the Short. The bridge was damaged by explosives in the final days of World War II. US troops threw the original Pepin into the river to make way for an anti-aircraft gun.[13]:32

- The Rathaus or city hall of Würzburg differs from those of most Imperial Cities in that it was not a sumptuous edifice purpose-built in Renaissance style. Rather, the motley collection of buildings and wings reflects the fact that after 1426 the city was permanently under the control of the bishop who did not allow a representative new building. The Rathaus consists of parts dating from 1339 (chapel), 1453 (tower with the town's first public clock), 1544 (southwest oriel), 1659/60 (Roter Bau). In 1822 the three-winged structure of the neighbouring Karmeliterkloster (monastery of the Carmelites) was added to the city hall. The "Renaissance" row on Karmeliterstrasse was built only in 1898.[13]:41

- Among Würzburg's many notable churches are the Käppele, a small Baroque/Rococo chapel by Balthasar Neumann, perched on a hill facing the fortress, and the Dom (Würzburg Cathedral). The Baroque Schönbornkapelle, a side-chapel of the cathedral, has interior decoration of (artificial) human bones and skulls. Also in the cathedral are two of Tilman Riemenschneider's most famous works, the tomb stones of Rudolf II von Scherenberg (1466–1495) and Lorenz von Bibra (1495–1519). At the entrance to the Marienkapelle (on the market square; built between 1377 and 1441) stand replicas of the statues of Adam and Eve by Riemenschneider.[9] The Neumünster is a Romanesque (11th century) minster church with a Baroque façade and dome. Its crypt (Kiliansgruft) houses the relics of Kilian, Totnan and Kolonat.[9] There are also two stone sarcophagi from the 8th century, the tombs of the first and second Bishop of Würzburg, Burkard and Megingaud. The latter's tomb features the oldest post-Roman monumental inscription in Franconia.[13]:45 Next to the Neumünster is the Lusamgärtchen. It contains a memorial from 1930 to Walther von der Vogelweide, who very likely was buried here in 1230.[13]:47 Only the church remains of the town's oldest abbey, St Burchard's Abbey founded around 750. It was transformed into a collegiate church in 1464 and dissolved in 1803. Among the Baroque churches in the centre of the city are Stift Haug (1670–1691), St. Michael, St. Stephan and St. Peter. The church of St Burkhard was built between 1033 and 1042, in the Romanesque style, and was restored in 1168. The Late Gothic choir dates from 1494–1497.[9]

- The Juliusspital is a Baroque hospital with a courtyard and a church originally established by prince-bishop Julius Echter in 1576. The 160 m long northern wing was added by Italian architect Antonio Petrini in 1700–1704. Beneath it lies the similarly-sized wine cellar, which (together with those of the Würzburg Residence and the Bürgerspital) offers a chance to taste the local Frankenwein in a special environment. The Juliusspital is the second largest winery in Germany, growing wine on 1.68 square kilometres (1 square mile).[13]:58–9 n

- The Haus zum Falken on Marktplatz, next to the Marienkapelle, with its ornate stucco façade, is an achievement of the Würzburg Rococo period. In the past it served as an inn, today it houses a public library and the tourist information office.[13]:62

- The Stift Haug (formally the Stiftskirche St. Johannis im Haug, dedicated to John the Baptist and John the Evangelist) was built in the years 1670–1691 as the first Baroque church in Franconia. It was designed by Antonio Petrini. The former church had been demolished as it was in the way of new city fortifications built by Johann Philipp von Schönborn. In 1945 most of the church's interior was destroyed. Works of art include a crucifixion by Tintoretto loaned by the Bavarian State Painting Collections.[13]:59–60

- The Würzburger Stein vineyard just outside the city is one of Germany's oldest and largest vineyards.

Museums and galleries

- The Museum für Franken (formerly the Mainfränkisches Museum) in the fortress is home to the world's largest collection of works by Tilman Riemenschneider. In a space of 5,400 m2 (58,125 sq ft), art by regional artists is exhibited. Exhibitions include a pre-historic collection, artifacts of the Franconian wine culture and an anthropological collection with traditional costumes.

- Fürstenbaumuseum: Also in the fortress, the restored Fürstenbau (former residence of the prince-bishops) houses not only the renovated living quarters, but also an exhibit on the history of Würzburg. Another exhibit features ecclesial gold jewelry and a collection of liturgical vestments. The museum also displays two models of the city: Würzburg in 1525 and Würzburg in 1945.

- Museum im Kulturspeicher, housed in a historic grain storage building combined with modern architecture, has more than 3,500 m2 of exhibit space. Collections include the "Peter C. Ruppert Collection", with European Concrete art after 1945 from artists such as Max Bill and Victor Vasarely; works from the Age of Romanticism, the Biedermeier period, Impressionism, Expressionism as well as contemporary art.

- Museum am Dom (Museum at the Cathedral), opened in 2003. It features about 700 pieces of art spanning the past 1000 years. The 1,800 m2 exhibit contrasts contemporary art with older works.

- Shalom Europe, a Jewish museum. Built around 1,504 tombstones discovered and excavated in the old city, the museum uses modern information technology to portray present and traditional Jewish lifestyles and their survival over the past 900 years in Würzburg.

- Martin von Wagner Museum, with objects from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. It is housed in the south wing of the Residence and displays ancient marble statues and burial objects. There are also ten exhibition halls with art from the 14th to the 19th centuries.

- Siebold-Museum, which houses permanent and temporary exhibits, including the estate of the 19th-century local physician and Japan researcher Philipp Franz von Siebold.[26]

- The Röntgen Memorial Site in Würzburg, Germany is dedicated to the work of the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923) and his discovery of X-rays, for which he was granted the Nobel Prize in physics. It contains an exhibition of historical instruments, machines and documents.

Sports

Former NBA basketball player Dirk Nowitzki was born and grew up in Würzburg. Nowitzki and numerous other German national team players started their careers at the local Baskets Würzburg club that plays in the Basketball Bundesliga as of 2016. In the past, the club played at international competitions such as the Eurocup.

Würzburg is also home to the football teams Würzburger Kickers playing in the 2. Bundesliga and Würzburger FV playing in the Fußball-Bayernliga.

SV Würzburg 05 is a swimming and water polo club, active in the German Water Polo League.

Governance

Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. The administration of the Landkreis Würzburg (district) is also located in the town.

Mayor

Since April 2014, the mayor of Würzburg has been Christian Schuchardt (CDU).

Politics

Education and research

Würzburg has several internationally recognized institutions in science and research:

University

The University of Würzburg (official name Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg) was founded in 1402 and is one of the oldest universities in Germany.

Academic disciplines are astronomy, biology, Catholic theology, chemistry, computer science, culture, economics, educational and social sciences, geography, history, languages and linguistics, law, literature, mathematics, medicine (human medicine, dentistry and biomedicine), pharmacy, philosophy, physics, political science, psychology and sociology.

Today, the ten faculties are spread throughout the city. The university currently enrolls approximately 29,000 students, out of which more than 1,000 come from other countries.

- Wilhelm Röntgen's original laboratory, where he discovered X-rays in 1895, is at the University of Würzburg.

- The University awarded Alexander Graham Bell an honorary Ph.D for his pioneering scientific work.

- The Botanischer Garten der Universität Würzburg is the university's botanical garden.

University of Applied Science

The University of Applied Sciences Würzburg-Schweinfurt was founded in 1971 as an institute of technology with departments in Würzburg and Schweinfurt. Academic disciplines are architecture, business economics, business informatics, civil engineering, computational engineering, computer science, electrical engineering, engineering management, geodesy, graphic design, logistics, mechanical engineering, media, nursing theory, plastics engineering, social work.

With nearly 8,000 students it is the second largest university of applied science in Franconia.

Conservatory

The Conservatory of Würzburg is an institution with a long tradition as well as an impressive success story of more than 200 years. It was founded in 1797 as Collegium musicum academicum and is Germany's oldest conservatory. Nowadays it is known as University of Music Würzburg. After the commutation from conservatory to university of music in the early 1970s, science and research were added to complement music education.

Fraunhofer Institute for Silicate Research

The "Fraunhofer ISC" in Würzburg is part of the Fraunhofer Society, Europe's largest application-oriented research organization. It develops materials for tomorrow's products, offering cooperation to small and medium-sized enterprises and to large-scale industrial companies.

Media

Würzburg is home to the daily newspaper Main-Post. Radio stations like Antenne Bayern and state broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk have local studios. The latter also maintains a large broadcasting station at Frankenwarte on the Nikolausberg. The private stations Radio Gong and Radio Charivari are based in Würzburg. The TV branch of Bayerischer Rundfunk has its Studio Mainfranken in the town. TV touring is a local private TV station.[28]

Transport

Roads

Due to its central position Würzburg is an important traffic hub. Here is the interchange of Autobahn highways A3 (Cologne – Frankfurt – Würzburg – Nuremberg) and A7 (Hamburg – Hanover – Kassel – Würzburg – Ulm) as well as the start of A81 (Würzburg – Heilbronn – Stuttgart). Furthermore, Bundesstraße highways B8, B13, B19 and B27 pass through the city.

Rail

The city's main station is a central hub for long-distance and regional services. Würzburg lies at the southern end of the Hanover-Würzburg high-speed rail line and offers with InterCityExpress and InterCity frequent connections to cities such as Cologne, Frankfurt, Hanover, Hamburg, Munich, Nuremberg and Vienna. In addition to main station there are the two regional stations Würzburg-South and Würzburg Zell.

| Long distance | Route | |

|---|---|---|

| ICE (Linie 25) |

Munich – Nuremberg – Würzburg – Kassel – Hanover – Hamburg | |

| Munich – Augsburg – Würzburg – Kassel – Hanover – Hamburg / – Bremen | ||

| ICE (Linie 31) |

Vienna – Linz – Passau – Nuremberg – Würzburg – Frankfurt (Main) – Mainz – Koblenz – Cologne – Wuppertal – Hagen – Dortmund | |

| ICE (Linie 41) |

Munich – Nuremberg – Würzburg – Frankfurt (Main) – Cologne – Düsseldorf – Essen | |

| regional | Route | |

|---|---|---|

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Kitzingen – Neustadt (Aisch) – Fürth – Nuremberg | |

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Aschaffenburg – Hanau – Frankfurt (Main) | |

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Osterburken – Heilbronn – Ludwigsburg – Stuttgart | |

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Schweinfurt – Bamberg – Lichtenfels – Hof/–Bayreuth | |

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Bamberg – Erlangen – Fürth – Nuremberg | |

| Regional-Express | Würzburg – Schweinfurt – Bad Kissingen / – Münnerstadt – Bad Neustadt – Mellrichstadt – Meiningen – Suhl – Arnstadt – Erfurt | |

| Regional train | Schlüchtern – Jossa – Gemünden (Main) – Würzburg – Schweinfurt – Bamberg | |

| Regional train | Karlstadt – Würzburg– Steinach – Ansbach – Treuchtlingen | |

| Regional train | Würzburg – Kitzingen | |

| Regional train | Würzburg – Bad Mergentheim – Weikersheim – Crailsheim | |

Trams/Trains

Würzburg has a tram network of five lines with a length of 19.7 kilometres (12.2 miles).

| Line | Route | Time | Stops |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grombühl – Sanderau | 20 minutes | 20 |

| 2 | Hauptbahnhof (Main station) – Zellerau | 14 minutes | 11 |

| 3 | Hauptbahnhof (Main Station) – Heuchelhof | 27 minutes | 20 |

| 4 | Sanderau – Zellerau | 23 min. | 18 |

| 5 | Grombühl – Rottenbauer | 39 minutes | 31 |

The proposed Line 6 from Hauptbahnhof (Main Station) to Hubland university campus via Residenz is scheduled to be completed after 2018.

Buses

27 bus lines connect several parts of the city and the inner suburbs. 25 bus lines connect the Landkreis Würzburg to the city.

Port

The Main river flows into the Rhine and is connected to the Danube via the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. This makes it part of a trans-European waterway connecting the North Sea to the Black Sea.

Bicycle

Designated bicycle paths are located throughout the city and the Main-Radweg long-distance bicycle trail passes through the old town.

Infrastructure

Utilities

The local public utility is Würzburger Versorgungs- und Verkehrs-GmbH supplying power, natural gas and water as well as public transportation and parking services. It also owns a majority stake in the port and runs local garbage collection/recycling. Heizkraftwerk Würzburg is owned by the utility.

Health care

Universitätsklinikum Würzburg provides health care services, with over 5,300 employees and over 1,400 hospital beds. Juliusspital also offers hospital services with 342 beds.

Notable people

- Joseph Friedrich Abert (1879–1959), historian and archivist

- Heinrich Albert (1870–1950), classical guitarist and composer

- Yehuda Amichai ("Ludwig Pfeuffer"; 1924–2000), Israeli poet

- Thomas Bach (born 1953), Olympic gold medalist in fencing & IOC President since 2013

- Frank Baumann (born 1975), footballer

- Fritz Bayerlein (1899–1970), World War II general

- Mark Bloch (born 1956), American artist

- Walter von Boetticher (1853–1945), historian and physician studied medicine at Würzburg

- Oskar Dirlewanger (1895–1945), war criminal and S.S. leader of the SS-Sturmbrigade Dirlewanger.

- Christian von Ditfurth (born 1953), writer and historian

- Jutta Ditfurth (born 1951), sociologist, writer and historian

- Freimut Duve (1936–2020), politician and author

- Björn Emmerling (born 1975), field hockey player

- Gottfried Feder (1883–1941), economist, anti-capitalist and national socialist

- Leonhard Frank (1882–1961), expressionist writer

- Manfred H. Grieb (1933-2012), entrepreneur and art collector

- Duane Harden (born 1971), dance music vocalist

- Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976), theoretical physicist

- Alfred Jodl (1890–1946), World War II general

- Klaus Iohannis (born 1959), President of Romania, elected 2014

- Wilhelm Keilmann (1908–1999), composer

- Cage Kennylz (born 1973), American hip-hop artist

- Friederich von Kleudgen (1856–1924), painter

- Maximilian Kleber (born 1992), basketball player

- Joseph Küffner (1776–1856), composer

- Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria (1821–1912)

- Ernst Mayr (1904–2005), evolutionary biologist

- Waltraud Meier (born 1956), opera singer

- Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn (1545–1617), Prince-Bishop of Würzburg and leader Counter Reformation

- Johann Balthasar Neumann (1687–1753), architect and military engineer

- Dirk Nowitzki (born 1978), basketball player

- Franz Oberthür (1745–1831), theologian

- Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460–1531), German sculptor and woodcarver

- Emy Roeder (1890–1971), expressionist sculptress and artist

- Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923), physicist, discovered X-rays

- Philipp Franz von Siebold (1797–1866), physician and botanist, among the first Westerners to visit and work in Japan

- Philipp Stöhr (1849–1911), anatomist

- Lorenz von Bibra (1459–1519), Prince-Bishop of Würzburg from 1495 to 1519

- Stephanie Wehner (born 1977), quantum physicist and computer scientist.

- Burkard Polster (born 1965), mathematician that runs the YouTube channel Mathologer.

Twinning

Würzburg has town twinning agreements with Bray, Co. Wicklow[29]

See also

- Bishopric of Würzburg

- 2016 Würzburg train attack

References

- "Tabellenblatt "Daten 2", Statistischer Bericht A1200C 202041 Einwohnerzahlen der Gemeinden, Kreise und Regierungsbezirke". Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung (in German). July 2020.

- John C. Wells. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary.

- "Würzburg". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Würzburg". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Würzburg" (US) and "Würzburg". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Würzburg". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Wuerzburg, Stadt. "Würzburg Online - Bevölkerung". www.wuerzburg.de. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Koch, John T. (2020). CELTO-GERMANIC Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West, p. 131

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 860.

- Norbert Wagner, 'Uburzis-Wirziburg "Würzburg"'

- Heinz Willner, Der Name Würzburg, Frankenland 1/1999.

- Stephanie Heyl, Stadt Würzburg (Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte). c.f. Siebmachers Wappenbuch (1605), plate 9.

- Dettelbacher, Werner (1974). Franken - Kunst, Geschichte und Landschaft (German). Dumont Verlag. ISBN 3-7701-0746-2.

- Wolfgang Behringer, Witchcraft in Bavaria: Popular Magik, Religious Zealotry, and Reason of State in Early Modern Europe, (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- "Würzburg During the Holocaust. Kristallnacht". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- The Story of the Jewish Community in Würzburg an online exhibition by Yad Vashem

- "Würzburg Subcamp". KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books, p. 65, 129.

- Seite 777, see also Chapter XVIII

- Wuerzburg, Stadt. "Rathaus | Würzburg in Zahlen - Stadtgebiet, Flächennutzung, Klima". www.wuerzburg.de. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- "Data" (PDF). www.wuerzburg.de. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- "Zensus 2011: Bevölkerung im regionalen Vergleich nach Religion (ausführlich) in %". Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- "Muslime in den Großstädten beim Zensus 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Bauer, Ralph (March 26, 2012). "Würzburg: GIs rissen sich um die erste Pizza in Deutschland" – via www.welt.de.

- "VGR der Länder, Kreisergebnisse für Deutschland - Bruttoinlandsprodukt, Bruttowertschöpfung in den kreisfreien Städten und Landkreisen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2000 bis 2017 (German)". Statistische Ämter der Länder und des Bundes. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "National Commission for Decentralised cooperation". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- "Data" (PDF). www.wuerzburg.de. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- "Town Twinning". wicklow.ie. Wicklow County Council. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

Further reading

- Avraham (Rami) Reiner, "The Role and Significance of the Titles written on the Tombstones in the Wurzburg Cemetery,"

- Congress – Tourismus – Wirtschaft (A municipal enterprise of the City of Würzburg): Würzburg. Visitors' Guide. Würzburg 2007. A leaflet.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Würzburg. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Würzburg. |

- Official website

(in German)

(in German) - The Story of the Jewish Community in Würzburg – on the Yad Vashem website