Gold leaf

Gold leaf is gold that has been hammered into thin sheets by goldbeating and is often used for gilding.[1] Gold leaf is available in a wide variety of karats and shades. The most commonly used gold is 22-karat yellow gold.

Gold leaf is a type of metal leaf, but the term is rarely used when referring to gold leaf. The term metal leaf is normally used for thin sheets of metal of any color that do not contain any real gold. Pure gold is 24 karat. Real, yellow gold leaf is approximately 91.7% pure (i.e. 22-karat) gold. Silver-colored white gold is about 50% pure gold.

Layering gold leaf over a surface is called gold leafing or gilding. Traditional water gilding is the most difficult and highly regarded form of gold leafing. It has remained virtually unchanged for hundreds of years and is still done by hand.

In art

Gold leaf is sometimes used in art in a "raw" state, without a gilding process. In cultures including the European Bronze Age it was used to wrap objects such as bullae simply by folding it tightly over, and the Classical group of gold lunulae are so thin, especially in the centre, that they might be classed as gold leaf. It has been used in jewellery in various periods, often as small pieces hanging freely.

Gold leaf has traditionally been most popular and most common in its use as gilding material for decoration of art (including statues and Eastern Christian icons) or the picture frames that are often used to hold or decorate paintings, mixed media, small objects (including jewelry) and paper art. Gold glass is gold leaf held between two pieces of glass, and was used for decorated Ancient Roman vessels, where some of the gold was scraped off to form an image, as well as tesserae gold mosaics. "Gold-ground" paintings, where the background of the figures was all in gold, was introduced in mosaics in later Early Christian art, and then used in icons and Western panel paintings until the late Middle Ages; all techniques use gold leaf. Gold leaf is also used in Buddhist art to decorate statues and symbols. Gold leafing can also be seen on domes in religious and public architecture. "Gold" frames made without leafing are also available for a considerably lower price, but traditionally some form of gold or metal leaf was preferred when possible and gold leafed (or silver leafed) moulding is still commonly available from many of the companies that produce commercially available moulding for use as picture frames.

Mycenaean necklace; 1400-1050 BC; gilded terracotta; diameter of the rosettes: 2.7 cm, with variations of circa 0.1 cm, length of the pendant 3.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mycenaean necklace; 1400-1050 BC; gilded terracotta; diameter of the rosettes: 2.7 cm, with variations of circa 0.1 cm, length of the pendant 3.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Flowering cherry and autumn maples with poem slips, a Japanese painting; by Tosa Mitsuoki; 1654–1681; pair of six-panel screens: ink, color, gold and silver on silk; height: 144 cm, width: 286 cm; Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, US)

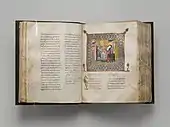

Flowering cherry and autumn maples with poem slips, a Japanese painting; by Tosa Mitsuoki; 1654–1681; pair of six-panel screens: ink, color, gold and silver on silk; height: 144 cm, width: 286 cm; Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, US) Byzantine Gospel lectionary; circa 1100; tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, and leather binding; overall: 36.8 × 29.6 × 12.4 cm, folio: 35 × 26.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Byzantine Gospel lectionary; circa 1100; tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, and leather binding; overall: 36.8 × 29.6 × 12.4 cm, folio: 35 × 26.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Byzantine icon of the New Testament Trinity; circa 1450; tempera and gold on wood panel (poplar); Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

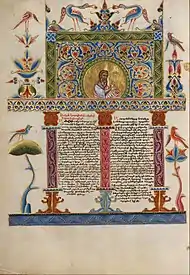

Byzantine icon of the New Testament Trinity; circa 1450; tempera and gold on wood panel (poplar); Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US) Page of an Armenian illuminated manuscript, in the Byzantine style; 1637–1638; tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment; height: 25.2 cm; Getty Center (Los Angeles)

Page of an Armenian illuminated manuscript, in the Byzantine style; 1637–1638; tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment; height: 25.2 cm; Getty Center (Los Angeles) Gothic leaf from a Gradual: Initial P with the Nativity; 1495; ink, tempera and gold on vellum; each leaf: 59.8 x 4.1 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

Gothic leaf from a Gradual: Initial P with the Nativity; 1495; ink, tempera and gold on vellum; each leaf: 59.8 x 4.1 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art Early 20th century leather book cover, with gold leaf ornamentation

Early 20th century leather book cover, with gold leaf ornamentation 22k gold leaf applied with an ox hair brush during the process of gilding

22k gold leaf applied with an ox hair brush during the process of gilding

In architecture

Gold leaf has long been an integral component of architecture to designate important structures, both for aesthetics and because gold's non-reactive nature provides a protective finish.

Gold in architecture became an integral component of Byzantine and Roman churches and basilicas in 400 AD, most notably Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. The church was built by Pope Sixtus III and is one of the earliest examples of gold mosaics. The mosaics were made of stone, tile or glass backed on gold leaf walls, giving the church a beautifully intricate backdrop. The Athenian marble columns supporting the nave are even older, and either come from the first basilica, or from another antique Roman building; thirty-six are marble and four granite, pared down, or shortened to make them identical by Ferdinando Fuga, who provided them with identical gilt-bronze capitals.[2] The 14th century campanile, or bell tower, is the highest in Rome, at 240 feet, (about 75 m.). The basilica's 16th-century coffered ceiling, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, is said to be gilded with gold that Christopher Columbus presented to Ferdinand and Isabella, before being passed on to the Spanish pope, Alexander VI.[3] The apse mosaic, the Coronation of the Virgin, is from 1295, signed by the Franciscan friar, Jacopo Torriti.

In Ottawa, Ontario, The Centre Block is the main building of the Canadian parliamentary complex on Parliament Hill, containing the House of Commons and Senate chambers, as well as the offices of a number of members of parliament, senators, and senior administration for both legislative houses. It is also the location of several ceremonial spaces, such as the Hall of Honour, the Memorial Chamber, and Confederation Hall. In the east wing of the Centre Block is the Senate chamber, in which are the thrones for the Canadian monarch and her consort, or for the federal viceroy and their consort, and from which either the sovereign or the governor general gives the Speech from the Throne and grants Royal Assent to bills passed by parliament.[4] The overall color in the Senate chamber is red, seen in the upholstery, carpeting, and draperies, and reflecting the color scheme of the House of Lords in the United Kingdom; red was a royal color, associated with the Crown and hereditary peers. Capping the room is a gilt ceiling with deep octagonal coffers, each filled with heraldic symbols, including maple leaves, fleur-de-lis, lions rampant, clàrsach, Welsh Dragons, and lions passant. This plane rests on six pairs and four single pilasters, each of which is capped by a caryatid, and between which are clerestory windows. Below the windows is a continuous architrave, broken only by baldachins at the base of each of the above pilasters.

On the east and west walls of the chamber are eight murals depicting scenes from the First World War; painted in between 1916 and 1920, they were originally part of the more than 1,000 piece Canadian War Memorials Fund, founded by the Lord Beaverbrook, and were intended to hang in a specific memorial structure. However, the project never eventuated, and the works were stored at the National Gallery of Canada until 1921, when the Parliament requested a loan for some of the collection's oil paintings to display in the Centre Block.[5][6] The murals have remained in the Senate chamber ever since.

In London, the Criterion Restaurant is an opulent building facing Piccadilly Circus in the heart of London. It was built by architect Thomas Verity in Neo-Byzantine style for the partnership Spiers and Pond who opened it in 1873. One of the restaurant’s most famous features is the 'glistering' ceiling of gold mosaic, coved at the sides and patterned all over with lines and ornaments in blue and white tesserae. The wall decoration accords well with the real yellow gold leaf ceiling, incorporating semi-precious stones such as jade, mother of pearl, turquoise being lined with warm marble and formed into blind arcades with semi-elliptical arches resting on slender octagonal columns, their unmolded capitals and the impost being encrusted with goldground mosaic [7]

Gold leaf adorns the wrought iron gates surrounding the Palace of Versailles in France, when refinishing the gates nearly 200 years after they were torn down during the French Revolution, it required hundreds of kilograms of gold leaf to complete the process.[8]

Apse of the Santa Maria Maggiore church from Rome, decorated in the 5th century with this glamorous mosaic

Apse of the Santa Maria Maggiore church from Rome, decorated in the 5th century with this glamorous mosaic.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Domes of churches from the Moscow Kremlin, covered with gold leaf

Domes of churches from the Moscow Kremlin, covered with gold leaf Interior of the Criterion Restaurant, built in the Byzantine Revival style

Interior of the Criterion Restaurant, built in the Byzantine Revival style

Culinary uses

Gold leaf (as well as other metal leaf such as vark) is sometimes used to decorate food or drink, typically to promote a perception of luxury and high value; however, it is flavorless.[9] It is occasionally found in desserts and confectionery, including chocolates, honey and mithai. In India it may be used effectively as a garnish, with thin sheets placed on a main dish, especially on festive occasions. When used as an additive to food, gold has the E-number E175. A traditional (centuries old) artisan variety of green tea contains pieces of gold leaf; 99% of this kind of tea is produced in Kanazawa, Japan, a historic city for samurai craftsmanship.[10] The city is also home to a gold leaf museum, Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum.

In Continental Europe liquors with tiny floating pieces of gold leaf are known of since the late 16th century; originally the practice was regarded as medicinal. Well-known examples are Danziger Goldwasser, originally from Gdańsk, Poland, which has been produced since at least 1598, Goldstrike from Amsterdam, Goldwasser from Schwabach in Germany, and the Swiss Goldschläger, which is perhaps the best known in both Canada and the United States.

See also

- Ormolu (aka bronz doré)

- Dutch metal

- Metallic dragée

- Tin(IV) sulfide – a compound used to imitate gold

References

- "gold leaf | art". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- Beny, Roloff; Gunn, Peter (1981). The Churches of Rome. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 106. ISBN 9780297779032.

- Charles A. Coulombe, Vicars of Christ, p. 330.

- Public Works and Government Services Canada. "A Treasure to Explore > Parliament Hill > History of the Hill > Centre Block > Senate". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 2009-09-14. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- Library of Parliament. "The War Paintings in the Senate Chamber > Introduction". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- Library of Parliament. "The War Paintings in the Senate Chamber > Foreword". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- "Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1", British History Online, 1960, retrieved 9 April 2015

- ""L'ameublement de la chambre de Louis XIV à Versailles de 1701 à nos jours"". gazette des Beaux-Arts (6th ed.): 79–104. February 1989.

- Hopkins, Jerry (2004). Extreme Cuisine: The Weird & Wonderful Foods that People Eat. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 289–292. ISBN 978-0794602550. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- "Japanese Culture/The Way/Tea ceremony/Let's Try". www.city.kanazawa.ishikawa.jp.

.jpg.webp)