Jade

Jade is an ornamental mineral, mostly known for its green varieties, though it appears naturally in other colors as well, notably yellow and white. Jade can refer to either of two different silicate minerals: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in the amphibole group of minerals), or jadeite (a silicate of sodium and aluminium in the pyroxene group of minerals).

| Jade | |

|---|---|

Unworked jade | |

| General | |

| Category | Mineral |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Identification | |

| Color | Virtually all colors, mostly green |

| Crystal habit | Intergrown grainy or fine fibrous aggregate |

| Cleavage | None |

| Fracture | Splintery |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6-7 |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent, opaque |

| Specific gravity | 2.9 - 3.38 |

| Refractive index | 1.600 - 1.688 |

| Birefringence | 0.020 - 0.027 |

| Pleochroism | Absent |

| Dispersion | None |

Jade is found in East Asian, South Asian and Southeast Asian art, but also has an important place in Mexico and Guatemala.The use of jade in Mesoamerica for symbolic and ideological ritual was highly influenced by its rarity and value among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Olmec, the Maya, and the various groups in the Valley of Mexico. Although jade artifacts have been created and prized by many Mesoamerican peoples, the Motagua River valley in Guatemala was previously thought to be the sole source of jadeite in the region.

Etymology

| Jade | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 玉 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 翡翠 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 옥, 비취 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 玉, 翡翠 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 玉, 翡翠 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The English word jade is derived (via French l'ejade and Latin ilia 'flanks, kidney area')[1] from the Spanish term piedra de ijada (first recorded in 1565) or 'loin stone', from its reputed efficacy in curing ailments of the loins and kidneys. Nephrite is derived from lapis nephriticus, a Latin translation of the Spanish piedra de ijada.[2]

History

Prehistoric and historic China

During Neolithic times, the key known sources of nephrite jade in China for utilitarian and ceremonial jade items were the now-depleted deposits in the Ningshao area in the Yangtze River Delta (Liangzhu culture 3400–2250 BC) and in an area of the Liaoning province and Inner Mongolia (Hongshan culture 4700–2200 BC).[3] Dushan Jade was being mined as early as 6000 BC. In the Yin Ruins of the Shang Dynasty (1600 to 1050 BC) in Anyang, Dushan Jade ornaments were unearthed in the tomb of the Shang kings.

Jade was considered to be the "imperial gem" and was used to create many utilitarian and ceremonial objects, from indoor decorative items to jade burial suits. From the earliest Chinese dynasties to the present, the jade deposits most used were not only those of Khotan in the Western Chinese province of Xinjiang but other parts of China as well, such as Lantian, Shaanxi. There, white and greenish nephrite jade is found in small quarries and as pebbles and boulders in the rivers flowing from the Kuen-Lun mountain range eastward into the Takla-Makan desert area. The river jade collection is concentrated in the Yarkand, the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers. From the Kingdom of Khotan, on the southern leg of the Silk Road, yearly tribute payments consisting of the most precious white jade were made to the Chinese Imperial court and there worked into objets d'art by skilled artisans as jade had a status-value exceeding that of gold or silver. Jade became a favourite material for the crafting of Chinese scholars' objects, such as rests for calligraphy brushes, as well as the mouthpieces of some opium pipes, due to the belief that breathing through jade would bestow longevity upon smokers who used such a pipe.[4]

Jadeite, with its bright emerald-green, pink, lavender, orange and brown colours was imported from Burma to China only after about 1800. The vivid green variety became known as Feicui (翡翠) or Kingfisher (feathers) Jade. It quickly became almost as popular as nephrite and a favorite of Qing Dynasty's nouveau riche, while scholars still had strong attachment to nephrite (white jade, or Khotan), which they deemed to be the symbol of a nobleman.

In the history of the art of the Chinese empire, jade has had a special significance, comparable with that of gold and diamonds in the West.[5] Jade was used for the finest objects and cult figures, and for grave furnishings for high-ranking members of the imperial family.[5] Due to that significance and the rising middle class in China, in 2010 the finest jade when found in nuggets of "mutton fat" jade – so-named for its marbled white consistency – could sell for $3,000 an ounce, a tenfold increase from a decade previously.[6]

The Chinese character 玉[7] (yù) is used to denote the several types of stone known in English as "jade" (e.g. 玉器, jadewares), such as jadeite (硬玉, 'hard jade', another name for 翡翠) and nephrite (軟玉, 'soft jade'). But because of the value added culturally to jades throughout Chinese history, the word has also come to refer more generally to precious or ornamental stones,[8] and is very common in more symbolic usage as in phrases like 拋磚引玉/抛砖引玉 (lit. "casting a brick (i.e. the speaker's own words) to draw a jade (i.e. pearls of wisdom from the other party)"), 玉容 (a beautiful face; "jade countenance"), and 玉立 (slim and graceful; "jade standing upright"). The character has a similar range of meanings when appearing as a radical as parts of other characters.

Head and torso fragment of a jade statuette of a horse, Chinese Eastern Han period (25–220 AD)

Head and torso fragment of a jade statuette of a horse, Chinese Eastern Han period (25–220 AD) Large "mutton fat" nephrite jade displayed in Hotan Cultural Museum lobby.

Large "mutton fat" nephrite jade displayed in Hotan Cultural Museum lobby. A selection of antique, hand-crafted Chinese jade buttons

A selection of antique, hand-crafted Chinese jade buttons

Prehistoric and historic Korea

The use of jade and other greenstone was a long-term tradition in Korea (c. 850 BC – AD 668). Jade is found in small numbers of pit-houses and burials. The craft production of small comma-shaped and tubular "jades" using materials such as jade, microcline, jasper, etc., in southern Korea originates from the Middle Mumun Pottery Period (c. 850–550 BC).[9] Comma-shaped jades are found on some of the gold crowns of Silla royalty (c. 300/400–668 AD) and sumptuous elite burials of the Korean Three Kingdoms. After the state of Silla united the Korean Peninsula in 668, the widespread popularisation of death rituals related to Buddhism resulted in the decline of the use of jade in burials as prestige mortuary goods.

Prehistoric and historic Japan

Jade in Japan was used for jade bracelets. It was a symbol of wealth and power. Leaders also used jade in rituals. It is the national stone of Japan.

India

The Jain temple of Kolanpak in the Nalgonda district, Telangana, India is home to a 5-foot (1.5 m) high sculpture of Mahavira that is carved entirely out of jade. India is also noted for its craftsman tradition of using large amounts of green serpentine or false jade obtained primarily from Afghanistan in order to fashion jewellery and ornamental items such as sword hilts and dagger handles.[10]

The Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad has a wide range of jade hilted daggers, mostly owned by the former Sultans of Hyderabad.

Southeast Asia

Today, it is estimated that Myanmar is the origin of upwards of 70% of the world's supply of high-quality jadeite. Most of the jadeite mined in Myanmar is not cut for use in Myanmar, instead being transported to other nations, primarily in Asia, for use in jewelry and other products. The jadeite deposits found in Kachinland, in Myanmar's northern regions is the highest quality jadeite in the world, considered precious by sources in China going as far back as the 10th century.

%252C_Artefacts_of_Phu_Hoa_site(Dong_Nai_province)_01.jpg.webp)

Jadeite in Myanmar is primarily found in the "Jade Tract" located in Lonkin Township in Kachin State in northern Myanmar which encompasses the alluvial region of the Uyu River between the 25th and 26th parallels. Present-day extraction of jade in this region occurs at the Phakant-gyi, Maw Se Za, Tin Tin, and Khansee mines. Khansee is also the only mine that produces Maw Sit Sit, a type of jade. Mines at Tawmao and Hweka are mostly exhausted. From to 1964 to 1981, mining was exclusively an enterprise of the Myanmar government. In 1981, 1985, and 1995, the Gemstone laws were modified to allow increasing private enterprise. In addition to this region, there are also notable mines in the neighboring Sagaing District, near the towns of Nasibon and Natmaw and Hkamti. Sagaing is a district in Myanmar proper, not a part of the ethic Kachin State.

Archaeologists have discovered two forms of jade artifacts that can be found across Taiwan in East Asia through the Philippines, East Malaysia, central and southern Vietnam, and even extending to eastern Cambodia and peninsular Thailand. These two forms are the lingling-o penannular earring with three pointed circumferential projections and the double animal-headed ear pendant. The ornaments are very similar in size and range from about 30–35 mm in diameter. Furthermore, radiocarbon dates have dated these artifacts in Southeast Asia from around 500 BC to 500 AD.[11] Electron probe microanalysis shows that the raw material of these two types of artifacts was nephrite jade from Taiwan called Fengtian nephrite (traditional Chinese: 豐田玉; simplified Chinese: 丰田玉; pinyin: Fēngtián Yù). Evidence recovered from multiple sites from Taiwan, the Philippines, and the mainland Southeast Asia suggests that Taiwan was the main source of the exchange of this kind of jade. During the Iron Age of Southeast Asia, there may have been skilled craftsmen traveling from Taiwan to Southeast Asia along the coastline of the South China Sea, making jade ornaments for local inhabitants.[11]

Māori

%252C_Maori_people%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art%252C_3351.JPG.webp)

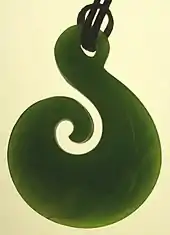

Nephrite jade in New Zealand is known as pounamu in the Māori language (often called "greenstone" in New Zealand English), and plays an important role in Māori culture. It is considered a taonga, or treasure, and therefore protected under the Treaty of Waitangi, and the exploitation of it is restricted and closely monitored. It is found only in the South Island of New Zealand, known as Te Wai Pounamu in Māori—"The [land of] Greenstone Water", or Te Wahi Pounamu—"The Place of Greenstone".

Pounamu taonga increase in mana (prestige) as they pass from one generation to another. The most prized taonga are those with known histories going back many generations. These are believed to have their own mana and were often given as gifts to seal important agreements.

Tools, weapons and ornaments were made of it; in particular adzes, the 'mere' (short club), and the hei-tiki (neck pendant). Nephrite jewellery of Maori design is widely popular with locals and tourists, although some of the jade used for these is now imported from British Columbia and elsewhere.[12]

Pounamu taonga include tools such as toki (adzes), whao (chisels), whao whakakōka (gouges), ripi pounamu (knives), scrapers, awls, hammer stones, and drill points. Hunting tools include matau (fishing hooks) and lures, spear points, and kākā poria (leg rings for fastening captive birds); weapons such as mere (short handled clubs); and ornaments such as pendants (hei-tiki, hei matau and pekapeka), ear pendants (kuru and kapeu), and cloak pins.[13][14] Functional pounamu tools were widely worn for both practical and ornamental reasons, and continued to be worn as purely ornamental pendants (hei kakï) even after they were no longer used as tools.[15]

Mesoamerica

Jade was a rare and valued material in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The only source from which the various indigenous cultures, such as the Olmec and Maya, could obtain jade was located in the Motagua River valley in Guatemala. Jade was largely an elite good, and was usually carved in various ways, whether serving as a medium upon which hieroglyphs were inscribed, or shaped into symbolic figurines. Generally, the material was highly symbolic, and it was often employed in the performance of ideological practices and rituals.

Canada

Jade was first identified in Canada by Chinese settlers in 1886 in British Columbia. At this time jade was considered worthless because they were searching for gold. Jade was not commercialized in Canada until the 1970s. The mining business Loex James Ltd., which was started by two Californians, began commercial mining of Canadian jade in 1972.[16]

Mining is done from large boulders that contain bountiful deposits of jade. Jade is exposed using diamond-tipped core drills in order to extract samples. This is done to ensure that the jade meets requirements. Hydraulic spreaders are then inserted into cleavage points in the rock so that the jade can be broken away. Once the boulders are removed and the jade is accessible, it is broken down into more manageable 10-tonne pieces using water-cooled diamond saws. The jade is then loaded onto trucks and transported to the proper storage facilities.[17]

Russia

Russia imported jade from China for a long time, but in the 1860s its own jade deposits were found in Siberia. Today, the main deposits of jade are located in Eastern Siberia, but jade is also extracted in the Polar Urals and in the Krasnoyarsk territory (Kantegirskoye and Kurtushibinskoye deposits). Russian raw jade reserves are estimated at 336 tons.[18] Russian jade culture is closely connected with such jewelry production as Faberge, whose workshops combined the green stone with gold, diamonds, emeralds, and rubies.

The mineral

Nephrite and jadeite

It was not until 1863 that French mineralogist Alexis Damour determined that what was referred to as "jade" could in fact be one of two different minerals, either nephrite or jadeite.[19]

Nephrite consists of a microcrystalline interlocking fibrous matrix of the calcium, magnesium-iron rich amphibole mineral series tremolite (calcium-magnesium)-ferroactinolite (calcium-magnesium-iron). The middle member of this series with an intermediate composition is called actinolite (the silky fibrous mineral form is one form of asbestos). The higher the iron content, the greener the colour. Tremolite occurs in metamorphosed dolomitic limestones and Actinolite in metamorphic greenschists/glaucophane schists.

Jadeite is a sodium- and aluminium-rich pyroxene. The more precious kind of jade, this is a microcrystalline interlocking growth of crystals (not a fibrous matrix as nephrite is.) It only occurs in metamorphic rocks.

Both nephrite and jadeite were used from prehistoric periods for hardstone carving. Jadeite has about the same hardness (between 6.0 and 7.0 Mohs hardness) as quartz, while nephrite is slightly softer (6.0 to 6.5) and so can be worked with quartz or garnet sand, and polished with bamboo or even ground jade. However nephrite is tougher and more resistant to breakage. Among the earliest known jade artifacts excavated from prehistoric sites are simple ornaments with bead, button, and tubular shapes.[20] Additionally, jade was used for adze heads, knives, and other weapons, which can be delicately shaped.

As metal-working technologies became available, the beauty of jade made it valuable for ornaments and decorative objects.

Unusual varieties

Nephrite can be found in a creamy white form (known in China as "mutton fat" jade) as well as in a variety of light green colours, whereas jadeite shows more colour variations, including blue, brown, red, black, dark green, lavender and white.[21] Of the two, jadeite is rarer, documented in fewer than 12 places worldwide. Translucent emerald-green jadeite is the most prized variety, both historically and today. As "quetzal" jade, bright green jadeite from Guatemala was treasured by Mesoamerican cultures, and as "kingfisher" jade, vivid green rocks from Burma became the preferred stone of post-1800 Chinese imperial scholars and rulers. Burma (Myanmar) and Guatemala are the principal sources of modern gem jadeite. In the area of Mogaung in the Myitkyina District of Upper Burma, jadeite formed a layer in the dark-green serpentine, and has been quarried and exported for well over a hundred years.[10] Canada provides the major share of modern lapidary nephrite.

Enhancement

Jade may be enhanced (sometimes called "stabilized"). Some merchants will refer to these as grades, but degree of enhancement is different from colour and texture quality. In other words, Type A jadeite is not enhanced but can have poor colour and texture. There are three main methods of enhancement, sometimes referred to as the ABC Treatment System:[22]

- Type A jadeite has not been treated in any way except surface waxing.

- Type B treatment involves exposing a promising but stained piece of jadeite to chemical bleaches and/or acids and impregnating it with a clear polymer resin. This results in a significant improvement of transparency and colour of the material. Currently, infrared spectroscopy is the most accurate test for the detection of polymer in jadeite.

- Type C jade has been artificially stained or dyed. The effects are somewhat uncontrollable and may result in a dull brown. In any case, translucency is usually lost.

- B+C jade is a combination of B and C: it has been both impregnated and artificially stained.

- Type D jade refers to a composite stone such as a doublet comprising a jade top with a plastic backing.

Industry

Myanmar

The jade trade in Myanmar consists of the mining, distribution, and manufacture of jadeite- a variety of jade- in the nation of Myanmar (Burma). The jadeite deposits found in Myanmar's northern regions are the source of the highest quality jadeite in the world, noted by sources in China going as far back as the 10th century. Chinese culture places significant weight on the meaning of jade; as their influence has grown in Myanmar, so has the jade industry and the practice of exporting the precious mineral.

Myanmar produces upward of 70 percent of the world's supply of high-quality jadeite.[23][24] Most of the Myanmar's jadeite is exported to other nations, primarily Asian, for use in jewelry, art, and ornaments. The majority of the production is carried out by Myanmar Gem Enterprise (MGE), a state-owned venture which has enough liquid assets to run itself for 172 years. [25]See also

- Cheonmachong – Tumulus of the Silla kingdom in Korea, containing jade artifacts

- Costa Rican jade tradition

- Jade burial suit

- Jade trade in Myanmar

- Mumun pottery period – Time in Korea when jade ornament production began

- Nephrite – A variety of jade

- Philippine jade artifacts

- Pounamu – Type of hard stone found in New Zealand, some of which are nephrite

- Serpentine subgroup – Group of minerals, some of which are known as false jade

- Name of 35th wedding anniversary

References

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- Easby, Elizabeth Kennedy. Pre-Columbian Jade from Costa Rica. (1968). André Emmerich Inc., New York

- Liu, Li 2003:3–15

- Martin, Steven. The Art of Opium Antiques. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 2007

- Jade. Gemstone.org

- Jacobs, Andrew (September 20, 2010). "Jade From China's West Surpasses Gold in Value". The New York Times. New York: NYTC. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- zh:玉

- Gem News, Gems & Gemology

- Bale, Martin T. and Ko, Min-jung. Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Pottery Period Korea. Asian Perspectives 45(2):159–187, 2006.

- Hunter, Sir William Wilson and Sir Richard Burn. The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Vol. 3. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, Henry Frowde Publishers (1907), p. 242

- Hung, H. C.; Iizuka, Y.; Bellwood, P.; Nguyen, K. D.; Bellina, B.; Silapanth, P.; and Manton, J. H. (2007). "Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(50), 19745–19750.

- Salt, Donn, 1992, Stone, Bone and Jade – 24 New Zealand Artists, David Bateman Ltd., Auckland.

- "Pounamu taonga". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Keane, Basil (2 March 2009). "Pounamu – jade or greenstone – Implements and adornment". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Collections Online – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Talbot, Matthew. "In Depth Green With Jade". Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- "What is Jade?". Polar Jade. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- Russian Nephrite: Mining and Value

- "Jade, greenstone, or pounamu?". Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Liu, Li. "The Products of Minds as Well as Hands: Production of Prestige Goods in Neolithic and Early State Periods of China". Asian Perspectives 42(1):1–40, 2003, p. 2.

- Grande, Lance; Augustyn, Allison (2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0.

- Tay Thye Sun. "The Changing Face of Jade" (PDF). Alumni Newsletter. Swiss Gemmological Institute (3): 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Egreteau, Renaud (October 11, 2011). "Jade or JADE? Debating International Sanctions on Burma's Gem Industry". Asia Pacific Journal (132).

- Hughes, Richard W. (2000) "Burmese Jade: The Inscrutable Gem, Part I: Burma's Jade Mines" Pala International

- Ryder, Brett. "Myanmar's state-owned enterprises show how much reform is still needed". Retrieved 7 July 2020.

Further reading

- Rémusat, Abel, 1820. Histoire de la ville de Khotan: tirée des annales de la chine et traduite du chinois ; Suivie de Recherches sur la substance minérale appelée par les Chinois PIERRE DE IU, et sur le Jaspe des anciens. Abel Rémusat. Paris. L’imprimerie de doublet. 1820. Downloadable from:

- Laufer, Berthold, 1912, Jade: A Study in Chinese Archeology & Religion, Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1974.

- Rawson, Jessica, 1975, Chinese Jade Throughout the Ages, London: Albert Saifer, ISBN 0-87556-754-1

- Ward, Fred (September 1987). "Jade: Stone of Heaven". National Geographic. Vol. 172 no. 3. pp. 282–315. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Jadeite sources in Mesoamerica (PDF)

- Between hell and the Stone of Heaven: Observer article on Jade Mining in Burma

- Old Chinese Jades: Real or Fake?

- Types of jade: 100 stone images with accompanying information

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jade. |

- Gemstone at Curlie

- The British Museum – 7,000 years of Chinese jade

- Gravity Measurement For Testing Jade (2008 archived version)

- mindat.org (Mineralogical data about Jade)

- Jade in Canada

- "Jade in British Columbia table", BC Govt MINFILE summary of jade showings and producers

- Canadian Rockhound magazine feature on jade