Grand River (Ontario)

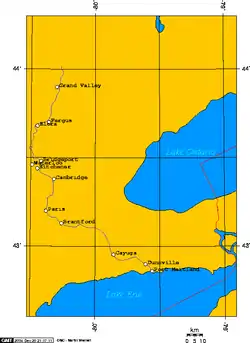

The Grand River (French: La Rivière Grand; Mohawk: Kenhionhata:tie) formerly known as The River Ouse is a large river in Southwestern Ontario, Canada. It also lies along the western fringe of the Greater Golden Horseshoe region of Ontario which overlaps the eastern portion of southwestern Ontario, sometimes referred to as Midwestern Ontario, along the length of this river. From its source near Wareham, Ontario, it flows south through Grand Valley, Fergus, Elora, Waterloo, Kitchener, Cambridge, Paris, Brantford, Caledonia, and Cayuga before emptying into the north shore of Lake Erie south of Dunnville at Port Maitland. One of the scenic and spectacular features of the river is the falls and Gorge at Elora.

| Grand River | |

|---|---|

A map of the Grand River's course | |

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Near Dundalk, Ontario |

| • elevation | 525 m (1,722 ft)[1] |

| Mouth | |

• location | Lake Erie at Port Maitland |

• elevation | 174 m (571 ft)[1] |

| Length | 280 km (170 mi)[1] |

The Grand River is the largest river that is entirely within southern Ontario's boundaries. The river owes its size to the unusual fact that its source is relatively close to the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron, yet it flows southwards to Lake Erie, rather than westward to the closer Lake Huron or northward to Georgian Bay (most southern Ontario rivers flow into the nearest Great Lake, which is why most of them are small), thus giving it more distance to take in more water from tributaries.

The river's mostly rural character (even when flowing through the edges of Waterloo and Kitchener), ease of access and lack of portages make it a desirable canoeing location, especially the stretch between West Montrose and Paris. A number of conservation areas have been established along the river, and are managed by the Grand River Conservation Authority.

The Grand Valley Trail stretches 275 km along the river's valley between the town of Dundalk and Lake Erie.

The Mohawk name for the Grand River, O:se Kenhionhata:tie means "Willow River," for the many willows in the watershed. During the 18th century, the French colonists named it Grande-Rivière. It was later renamed as Ouse River by John Graves Simcoe for the River Great Ouse near his childhood home in Lincolnshire on the east coast of England. The anglicized form of the French name has remained in common use.

Watershed

The Grand River watershed consists of all the land that drains into the Grand River through tributary creeks and rivers such as the Conestogo, Speed, Eramosa, Irvine and Nith rivers. The Grand River has Southern Ontario's largest watershed.[2][3][4][5][6]

Because the watershed is an ecosystem with natural borders, it includes and crosses many municipal boundaries and can be considered a transitional area between Southwestern Ontario and the Golden Horseshoe region that surrounds the west end of Lake Ontario. Its headwaters are near Dundalk in the north. The Grand River flows south-south-east.

Luther Marsh, a 52-square-kilometre wetland on the upper Grand, is one of the largest inland wetlands in southern Ontario and provides habitat for waterfowl, including least bittern and black tern, and amphibians. It is also an important staging area during bird migrations. The importance of the watershed (7000 square kilometers or 2600 square miles) has been recognized by the designation of the Grand as a Canadian Heritage River.

The Grand Valley Dam, located near the village of Belwood, helps to control the flow of water, especially during periods of spring flooding. The dam, completed in 1942, is commonly referred to as Shand Dam, named for a local family who were displaced by filling of the dam's reservoir, Lake Belwood.[7]

Lakes, creeks and rivers

With a watershed area of 7,000 square kilometres (2,700 sq mi), the Grand River flows from Dundalk to Lake Erie with numerous tributaries flowing into it:[8]

- Canagagigue Creek

- Chilligo Creek

- Conestogo River

- Eramosa River

- Fairchild Creek

- Idlewood Creek

- Irvine Creek

- Knob Creek

- Laurel Creek

- McKenzie Creek

- Mill Creek

- Nith River

- Schneider Creek

- Speed River

- Spencer Creek

- Whitemans Creek

The Conestogo River joins the Grand at the village of Conestogo just north of Waterloo.[3] The Eramosa River joins the Speed River in Guelph.[5][6] The Speed River joins the Grand in Cambridge. The Nith River joins the Grand in Paris.[4]

Pre-Laurentide hydrology

Prior to the most recent glaciation—the Laurentide—an earlier river flowed through a gorge roughly parallel to the current Grand River.[9] Evidence of the "buried gorge" of the previous river has been found when wells have been drilled. Rather than finding water-bearing bedrock at a depth of a dozen metres or less, the path of the buried gorge can be found with overburden of dozens of metres.

History

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Grand River valley was inhabited by the Iroquoian- speaking Attawandaron nation. They were later given the name "Neutral Nation" by European settlers, as they refused to side with either the French or the English during their conflicts in the area.

The Wyandot, another distinct Iroquoian-speaking nation, who resided northeast of the Grand River valley, had long competed to remain independent of their enemy the Iroquois Confederacy, a powerful alliance of five nations based around the Great Lakes in the present central and western New York state area. Caught in between, the Neutrals paid dearly for their refusal to ally. Historical accounts differ on exactly how the Neutral tribe was wiped out. The consensus is that the Seneca and the Mohawk nations of the Iroquois destroyed the smaller Neutral tribe in the 17th century, in the course of attacking and severely crippling the Huron/Wyandot. The Iroquois were seeking to dominate the lucrative fur trade with the Europeans. It was during this warfare that the Iroquois attacked the Jesuit outpost of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons. The Jesuits abandoned the mission after many Wyandot and numerous priests were killed here.

To survive, remnants of The Neutral tribe migrated in 1667 to La Prairie (Caughnawaga or Kahnawake), a Catholic mission settlement just south of Montreal that was occupied primarily by converted Mohawk who had migrated north from New York. In 1674 identifiable groups of Neutrals were recorded among its population. It can be presumed that many of their descendants are still living there today. In later wars between Britain and France, the Caughnawaga people, many of whom had converted to Catholicism, were allies of the French. The Iroquois League in New York then was neutral or sided with the British. Because different nations were on different sides in this war, it was difficult for the Iroquois nations to adhere to the Great Law of Peace and avoid killing each other. They managed to avoid such bloodshed until the American Revolution (1775–83).

Other descendants of the Neutrals may have joined the Mingo, a loose confederacy of peoples who moved west in the 1720s, fleeing lands invaded by Iroquois, and settled in present-day Ohio. The Mingo were among tribes who later fought the Americans in the Northwest Indian Wars for the Ohio Valley (1774–95). During the 1840s, they were among the tribes removed to Oklahoma and Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Neutral descendants are among the people now known as the Seneca in Oklahoma.

After the desolation of the Neutral tribe, the Iroquois Confederacy used the Grand River Valley as a hunting ground and trapping territory. Though the Six Nations (by then including the Tuscarora) held the territory by right of conquest, they did not settle it, apart from a limited presence on the northern and western shores of Lake Ontario.

When the French explorers and Coureurs de bois came to the region in search of fur and other items of value to Europeans, the Grand River Valley was among the last areas of southern Ontario to be explored. Since the French worked closely with their Native allies in the acquisition of fur and trading of European goods for it, they went only where the natives resided. Even after the English conquered New France in 1760 during the Seven Years' War, the Grand River Valley remained largely unoccupied and largely uncharted.

An explorers' map in 1669 showed the River as being called the Tinaatuoa or Riviere Rapide. A 1775 map shows it as Urse, a name which also appeared on a 1708 map and on Bellin’s Carte des Lacs of 1744. The d’Anville map of 1755 shows the river Tinaatuoa but adds the words Grande River at its mouth. Other 18th Century names were Oswego and Swaogeh. In 1792, Simcoe tried to change the name of Grande Riviere to Ouse, after a river in England and the Thomas Ridout map of 1821 shows "Grand R or Ouse".[10] Simcoe failed because the name Grand River had been in common usage for some time by then.[11]

Six Nations of the Grand River

Apart from large numbers of Tuscarora and Oneida, who mainly allied with the American colonists, the other four nations of the Iroquois Confederacy sided with the British during the American War of Independence. Warfare throughout the frontier of the Mohawk Valley had resulted in massacres and atrocities on both sides, aggravating anti-Iroquois feelings among the colonists. Without consultation or giving the Iroquois a place in negotiations, the British ceded their land in New York to the new United States.

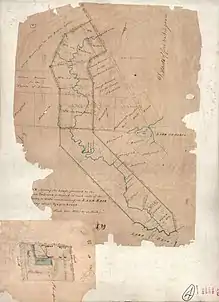

The Iroquois were unwelcome in the newly created nation. After the war, Six Nations leader Joseph Brant appealed to the British Crown for help, as they had promised aid for allies. In gratitude for their assistance during the war, the Crown awarded the Iroquois land in Upper Canada. Brant led Mohawk from the Upper Castle and families of the other Six Nations to Upper Canada. They first settled at what is present-day Brantford, where Brant crossed, or ‘forded’ the Grand River. It was also called Brant's Town. Not all members of the Six Nations moved north. Remnants of the past confederacy live today throughout New York state, some on federally recognized reservations. In 1784 the British Crown awarded to the Six Nations the "Haldimand Tract",[12] a tract of land "six miles deep from each side of the river beginning at Lake Erie and extending in that proportion to the [source] of the said river."[13] Much of this land was later sold or otherwise lost to the Six Nations.

A portion of this tract near Caledonia, Ontario is the basis for the 2006 Caledonia land dispute, in which the Six Nations filed a land claim with the government. The Six Nations reserve south of Brantford, Ontario is what remains of the Haldimand Tract. Throughout the 19th century, many Anglo-Canadian settlements developed along the Grand within former Six Nations territory, including Waterloo, Berlin (now Kitchener), Cambridge, Paris, Brantford, Caledonia, Dunnville and Port Maitland.

After the American War of Independence, the Crown purchased land from the Mississaugas in Upper Canada to award as grants to Loyalist refugees as compensation for their property losses in the colonies. Loyalists from New York, New England and the South were settled in this area, as the Crown hoped they would create new towns and farms on the frontier. In the 19th century, many new immigrants came to Upper Canada from England, Scotland, Ireland and Germany seeking opportunity. Settlements were popping up all over Southern Ontario, and many colonists coveted the prize Grand River Valley.

The 1846 Gazetteer relates the history of the First Nations of the area as follows:

"In 1784, Sir F. Haldimand ... granted to the Six Nations and their heirs for ever, a tract of land on the Ouse, or Grand River, six miles in depth on each side of the river, beginning at Lake Erie, and extending to the head of the river. This grant was confirmed, and its conditions defined, by a patent under the Great Seal, issued by Lieutenant Governor Simcoe, and bearing date January 14, 1793...The original extent of the tract was 694,910 acres, but the greater part of this has been since surrendered to the Crown, in trust, to be sold for the benefit of these tribes. And some smaller portions have been either granted in fee simple to purchasers with the assent of the Indians, or have been alienated by the chiefs upon leases; which, although legally invalid, the government did not at the time consider it equitable or expedient to cancel."[14]

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2008-10-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

-

Greg Mercer (2018-08-18). "The Watershed: Ever-changing Grand River". Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

We have left our imprint on the river, just as much as it's left it's [sic] imprint on our region. In the 19th century, European settlement reduced the river's natural water flows by converting thousands of hectares of forest and wetlands into farmland.

-

Greg Mercer (2018-08-09). "The Watershed: Crashing and banging down the Conestogo". Waterloo Region Record. St. Jacobs, Ontario. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09.

Named by Mennonite settlers after the Conestoga River in Pennsylvania, the Conestogo snakes through farmland of Mapleton, Wellesley and Woolwich townships, past the northern edge of Waterloo and under the roar of the Highway 85 bridge before draining into the Grand.

-

Greg Mercer (2018-07-21). "The Watershed: Life and death on the Nith River". Waterloo Region Record. New Hamburg, Ontario. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09.

But the Nith is also a river of split personalities. At times, it turns into a raging, roaring beast during spring thaws or flash floods. It's a river that can flood basements, destroy homes and, yes, even kill.

-

Greg Mercer (2018-08-03). "The Watershed: Paddling Eramosa, the 'little gem'". Waterloo Region Record. Eden Mills. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09.

The Eramosa springs up from its origins outside of Erin, passes through hundreds of glacial potholes in Rockwood and babbles over a stone riverbed that runs westward across Wellington County. At Guelph, it joins the Speed River, which connects to the Grand River in Cambridge.

-

Greg Mercer (2018-08-10). "The Watershed: Speed River comes back to life". Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09.

Today, the lower part of the Speed River is on the rebound. It's home to snapping turtles, mink, beavers, muskrat, dozens of bird species and fish such as pike, trout and bass.

- Grand River (1945) by Mabel Dunham

- Where is the Grand?, archived from the original on 8 September 2006, retrieved 21 November 2009

- John P. Greenhouse. "The other Elora Gorge - Ancient gorge causes frustrations for well diggers". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 2015-04-08. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "Thomas Ridout Map 1821". Wikimedia Commons. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- "History" (PDF). Waterloo Historical Society 1930 Annual Meeting. Waterloo Historical Society. 1930. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- A Map: the Six Nations' opinion of the location of the disputed 1784 Haldimand Tract Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, reclamation.kisikew.org

- Charles M. Johnston, ed. (1964). The Valley Of The Six Nations. The Champlain Society For The Government of Ontario, University of Toronto Press. pp. 50–51.

- Smith, Wm. H. (1846). SMITH'S CANADIAN GAZETTEER - STATISTICAL AND GENERAL INFORMATION RESPECTING ALL PARTS OF THE UPPER PROVINCE, OR CANADA WEST:. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. pp. 67–68.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand River (Ontario). |