Great northern tilefish

The great northern tilefish (Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps) or golden tile, is the largest species in the family Malacanthidae (tilefishes), which grows to an average length between 38 to 44 inches (970 to 1,120 mm). The great northern tilefish is a slow-growing and long-lived species, which has four stages of life. After hatching from eggs, the larvae are found in plankton. As they grow into juveniles, the individuals seek shelter until finding or making their own burrows. As adults, the tilefish continue to expand their burrows in the sediment throughout their lives. The diet of the larvae is unknown, but presumed to consist of zooplankton; juveniles and adults feed upon various benthic invertebrates, crustaceans, and fish. After reaching sexual maturity between 5 and 7 years of age, females lay eggs throughout the mating season for the male to fertilize, with each female laying an average of 2.3 million eggs.

| Great northern tilefish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. chamaeleonticeps |

| Binomial name | |

| Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps Goode & T. H. Bean, 1879 | |

| |

The great northern tilefish has been subject to regulation to prevent overfishing. Regulations include catch limits and gear restrictions to prevent damage to the species' habitat and population. The result of these regulations has been a rebounding of the population, which led to an increase in the 2012 catch limit in the southern part of the Atlantic seaboard.[Note 1]

Taxonomy and naming

The species was first discovered in 1879, when a cod trawler caught some by chance while working off of the coast of Massachusetts.[3] The species was named Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps by George Brown Goode and Tarleton Hoffman Bean in 1896 in their seminal work Oceanic Ichthyology, A Treatise on the Deep-Sea and Pelagic Fishes of the World, from a sample collected 80 miles (130 km) southeast of Nomans Land, Massachusetts.[4] The discovery of the fish was announced earlier in the journal Science (see "The Tile-Fish" in Science, Vol. 5. No. 101 (January 9, 1885), pages 29–30). Its genus is Lopholatilus, which is in the family Malacanthidae, commonly known as tilefish. The Malacanthidae are part of the Percoidea, a suborder of the order Perciformes.[5] L. chamaeleonticeps gained its moniker "great northern tilefish" from its prodigious size and its discovery at relatively high latitudes for a member of the Malacanthidae. When used in cooking, the species is generally referred to as the "golden tile", for the large yellow spots across its blue-green back and lighter-yellow or pink sides.[3] The species is distinguished from other members of its large family by a prominent crest on its head.[6]

Characteristics

The great northern tilefish is the largest species of the family Malacanthidae; male specimens can grow up to 112 cm (44 in) fork length (FL)[7] and females to 100 cm (39 in) FL. During their first four years of life, they grow at a rate of typically 10cm/yr after which their rate of growth slows down. They reach sexual maturity once they are between 50 and 70 cm (20 and 28 in) in length[8] Various studies have shown that the life expectancy of fish that survive into adulthood is in the range of 25 to 35 years.[9]

The back of the fish is iridescent and blue-green in color, with many yellow and gold spots.[6][10] The belly is white. The head color changes from a light blue to a pinkish mix during spawning season. Specimens have a tone of blue under their eyes. Their pectoral fins are a light tone of sepia, and the margin of the anal fin is a purplish-blue color.[6]

Lengths at age suggest that males grow faster than females, but the observed ages showed that females live longer. The largest male specimen was 44.1 in (1,120 mm) long and about 20 years old, the largest female specimen was 39 years old and reached a total length of 40.2 in (1,020 mm). The oldest tilefish recorded to date was a 46-year-old female specimen that reached a length of 33.5 in (850 mm), while the oldest recorded male specimen was 41.3 in (1,050 mm) and 29 years.[11]

Behavior

The great northern tilefish has a unique burrowing behavior and habitat preference. In addition to their unique habitat choice, golden tilefish display sexually dimorphic growth with males growing to larger sizes and are behaviorally dominant over their female counterparts.[12] The great northern tilefish is not a migratory fish; it stays in one local area that fits its needs all year round.[8] Seasonal migration may occur with changes in the water temperatures around the Nantucket Shoals and Georges Bank during the winter or spring, but this theory has no definitive evidence. A competing theory suggests that tilefish may instead reduce their activity or hibernate within their burrows during times of cold temperatures.[13]

The lifecycle of the great northern tilefish begins as an egg, which is nonadhesive and buoyant. Eggs that are artificially fertilized and kept in an environment between 71 and 76 °F (22 and 24 °C) hatch after 40 hours. The hatching larvae are around 0.1 in (2.5 mm) in length. The larvae are found in plankton from July to September in the Middle Atlantic Bight. The transitional phase between larvae and juveniles is unknown, but juveniles either find or excavate a burrow or place of shelter to inhabit. After they grow in size and become sexually active, the adults spawn throughout the mating season to propagate the species.[13]

The tilefish's construction and expansion of burrows are the subject of ongoing research to better understand the behavior of the species. Whether the tilefish begins the construction a burrow or if it expands an existing one is unknown. The burrow is presumed to be lengthened and widened by the tilefish as it continues to grow and age.[13] Tilefish typically are found in their own burrows, with sharing exhibited with male and female pairs. Tilefish tend to congregate in their habitat, with their burrows in relative proximity to each other; the species does not form schools.[13] The grouping of tilefish can be as dense as 13,000 burrows per km2 off the southern U.S. Atlantic coast, but 1,600 burrows per km2 were reported in inhabited areas of the Gulf of Mexico and 2,500 burrows per km2 near the Hudson Canyon.[13] Tilefish burrows also provide a home for various species that live in the area, such as mollusks and other crustaceans.[8]

Predation

The predators of the tilefish are poorly understood. Juveniles can be preyed upon by dogfish or conger eels, which are prey for adult tilefish. Sharks have been presumed be predators of the tilefish, but no evidence is seen of free-swimming tilefish being attacked by dusky sharks or sandbar sharks. The one listed predator for the tilefish is the goosefish.[13] The function of the tilefish's burrows was predator avoidance, but this has been disputed because chased tilefish try to outswim their predators rather than entering their burrows to seek shelter.[13][14]

Diet

The diet of tilefish larvae is unknown, but it is believed to be zooplankton.[13] Juvenile and adults are omnivorous with a preference for small benthic invertebrates, with a staple being crabs and lobster.[13] Great northern tilefish also consume bivalve molluscs, salps, squid, Atlantic dogfish, mackrel, hagfish, and herring. Human trash is also eaten, including potato peels and meat bones.[13] They also eat other tilefish in a display of cannibalistism.[15]

Reproduction

The fish spawn during the early spring to the late fall, from March to November. Peak spawning occurs during May to September in Mid-Atlantic Bight[Note 2] regions, differences in temperatures affect the breeding time. In U.S waters further south, the spawning season occurs from April to June. Males grow faster and reach larger sizes than females. Fishing pressure may cause males to spawn at smaller sizes, and at younger ages.[17]

The spawning behavior of the species is unknown, but it is presumed to be polygamous with the female choosing the male. Pair bonding has been exhibited, which is assumed to be a behavior that serves to insure fertilization of the eggs during the season.[13] It was estimated that females can spawn about every four days for a total of 34 times per season.[8] Depending on the size, the average female may lay 195,000 – 8 million eggs during spawning season, with the average female laying 2.3 million eggs.[18]

In response to the overfishing, the tilefish's age of sexual maturity has been dramatically affected. From 1978 to 1982, the median age of sexual maturity in males declined by 2.5 years from 7.1 to 4.6 years. This resulted in the males becoming sexually mature before females. In 2008, the median age of sexual maturity in males had risen to 5.9 years. Females of the species also exhibit low reproductive ability after becoming sexually mature, instead increasing with age and their sexual maturity has varied to a lesser extent than the male population across the years.[19]

A small percentage of golden tilefish is known to be intersexual, having opposite nonfunctional sex tissues. Male tilefish specimens also inhibited a cavity that came from ovarian tissue and sperm sinuses.[20] Tilefish of both genders in the Gulf of Mexico exhibited a higher rate of intersex characteristics than other populations.[19]

Distribution and habitat

The species is abundant in the United States territorial waters of the Atlantic Ocean extending north into Nantucket Shoals and Georges Bank and moving south along the East Coast of the United States and into the Gulf of Mexico along the continental shelf.[13][21] Although Great northern tilefish are reported to be most abundant between 300 and 480 feet (91 and 146 m) deep at 76 °F (24 °C).,[22] the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report differs, by stating that the species lives at the bottom of the ocean where they burrow into the sediment, between 250 and 1,500 feet (76 and 457 m) deep where the temperature ranges from 49 to 58 °F (9 to 14 °C).[23]

The great northern tilefish is known to dig and occupy burrows along the outer continental shelf, and on the flanks of submarine canyons in malleable clay substrate.[24][25] Due to their long life expectancy, slow growth, complex breeding system, and habitat specificity, they are vulnerable to overexploitation, and they are susceptible to mass mortality events due to cold-water intrusion and overfishing. Their abundance is strongly correlated with presence of silt-clay substrate, because the soft clay enables the fish to create the burrow itself by simply digging away the clay substrate.[26] The minimum temperature threshold for golden tilefish is 9 °C (48 °F). Temperature observations and measurements are obtained by interpolated observations. Temperature plots indicate that 9 °C is the norm for the area around Florida and the Gulf of Mexico.[27]

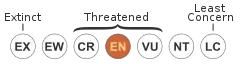

Population and conservation status

Decline in age, size during sexual maturity in great northern tilefish population is occurring throughout the continental shelf. In the mid-Atlantic Bight, smaller sizes and younger ages at maturity were observed in 2008, compared to the survey data from the 1980s where recorded measurements showed a larger population. The recent estimates of age and size at maturity in the southern U.S. waters were smaller than those previously reported in the late 1980s. There were also very few juvenile tilefish seen in tilefish population surveys in the southern U.S. waters in both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.[28] Declines in population could negatively affect other organisms in their surrounding environment due to the fact that without tilefish, the burrows underneath the continental shelf will disappear, therefore putting an end to the symbiotic relationship with other organisms that use the tunnels as shelter.[29][30]

Fishing regulations include catch limits and gear restrictions to prevent damage to the species habitat and population. There are different gear restrictions for commercial and recreational fishers.[31] In 2007, regulations were imposed to reduce the harvesting by one third, as a response to overfishing in the South Atlantic.[32] The South Atlantic catch limit was later increased in October 2012 as a response to the increased population.[33] The 2013 limits in the southern U.S. Atlantic waters for the species, measured in gutted weight, were 405,971 pounds for longline and 135,324 pounds for hook-and-line fishing.[34] The current South Atlantic catch limits as of 2019 are 248,805 pounds for longline and 82,935 pounds for hook-and-line fishing.[35]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps. |

- The literature in this article uses the term "South Atlantic" to refer to the Atlantic Ocean off the states off North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.[2]

- The literature in this article uses the term "Mid Atlantic" to refer to the Atlantic Ocean off the states off New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.[16]

References

- Aiken, K.A., Collette, B., Dooley, J., Kishore, R., Marechal, J., Pina Amargos, F. & Singh-Renton, S. (2015). Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T16545046A16546277.en

- "About us". South Atlantic Fishery Management Council. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Goodwin, G; Bogert, C M; Gilliard, E; Coates, C W; "The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Animal Life", Odham Books, 1961. Vol. 13, pp. 1539–1540.

- Goode, G. B.; Bean, T. H. (1896) Oceanic Ichthyology, A Treatise on the Deep-Sea and Pelagic Fishes of the World, Based Chiefly upon the Collections Made by the Steamers Blake, Albatross, and Fish Hawk in the Northwestern Atlantic, caption for Pl. LXXV. 265. Retrieved from the NOAA Photographic Library, July 24, 2007

- Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2006). Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps blue tilefish. The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed July 24, 2007

- "The Golden Tilefish". safmc.net. South Atlantic Fishery Management Council. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Standard Measurements of Bony Fish". Florida Museaum of Natural History. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- Steimle, Frank W.; Zetlin, Christine A.; Berrien, Peter L.; Johnson, Donna L.; Chang, Sukwoo (September 1999). "Tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps, Life History and Habitat Characteristics" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-152. p. 7.

- Lombardi-Carlson, Linda Anne. Life History, Population Dynamics, and Fishery Management of the Golden Tilefish, Lopholatilus Chamaeleonticeps, from the Southeast Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico (PhD). University of Florida. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Meadows, Jean; King, Mary. "Florida Food Fare: Tilefish" (PDF). University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Golden Tilefish AP Information Document1 - January 2013" (PDF). MAFMC. Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council. January 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Golden tilefish (Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps) age, growth, and reproduction from the northeastern Gulf of Mexico: 1985, 1997-2009" (PDF). NOAA. 2009. p. 3. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-152 Essential Fish Habitat Source Document: Tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps , Life History and Habitat Characteristics" (PDF). Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Myers, James (1991). Micronesian reef fishes. Barrigada, Guam: Second Ed. Coral Graphics. p. 298. ISBN 0962156426.

- "Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps Goode & Bean, 1879". Fish Base. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "About the Council". Mid Atlantic Fishery Management Council. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Golden Tilefish" (PDF). blueocean.org. Blue ocean. p. 3. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Seafood Watch Seafood Report" (PDF). Monterey Bay Aquarium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- McBride, Richard S.; Vidal, Tiffany; Cadrin, Steven (2013). "Changes in size and age at maturity of the northern stock of Tilefish (Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps) after a period of overfishing" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. National Marine Fisheries Service. 11 (2): 161–174. doi:10.7755/FB.111.2.4.

- "Life History, Population Dynamics, and Fishery Management of the Golden Tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps". George A. Smathers Libraries. University of Florida, PhD thesis. 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Tilefish – Status of Fishery". NOAA. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Golden Tilefish". sea2table.com. Sea To Table. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "NOAA Fishwatch Golden Tile Fish". NOAA Fishwatch. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Sullivan, Walter (July 22, 1986). "Burrowing Fish found Shaping the seafloor". The New York Times.

- "Miami Fishing Report". Fishing miami charter. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Panama City Laboratory, Life History and Habitat Requirements of Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps in the Gulf of Mexico, NOAA, November 10, 2001. Retrieved 13 July, 2007.

- John Walter. "Explorations of habitat associations of yellowedge grouper and golden tilefish" (PDF). NOAA. NOAA. p. 4. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Golden Tilefish" (PDF). blueocean.org. Blue Ocean. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Northern Tilefish". Vancouver aquarium. Oceanwise. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- Wiseman, Clay (1991). Guide to Marine Life. Aqua Quest Publications. p. 181. ISBN 9781881652069.

- "Allowable Gear for the Snapper-Grouper Fishery" (PDF). Safmc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "Overview". Fishwatch. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "NOAA Fisheries Announces New Regulations for Golden Tilefish in the South Atlantic" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "Frequently Asked Questions for New Regulations for South Atlantic Golden Tilefish" (PDF). South Atlantic Fishery Management Council. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "2019 Preliminary South Atlantic Commercial Landings". NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved 13 September 2019.