Shoaling and schooling

In biology, any group of fish that stay together for social reasons are shoaling, and if the group is swimming in the same direction in a coordinated manner, they are schooling.[1] In common usage, the terms are sometimes used rather loosely.[1] About one quarter of fish species shoal all their lives, and about one half shoal for part of their lives.[2]

Fish derive many benefits from shoaling behaviour including defence against predators (through better predator detection and by diluting the chance of individual capture), enhanced foraging success, and higher success in finding a mate. It is also likely that fish benefit from shoal membership through increased hydrodynamic efficiency.

Fish use many traits to choose shoalmates. Generally they prefer larger shoals, shoalmates of their own species, shoalmates similar in size and appearance to themselves, healthy fish, and kin (when recognized).

The "oddity effect" posits that any shoal member that stands out in appearance will be preferentially targeted by predators. This may explain why fish prefer to shoal with individuals that resemble themselves. The oddity effect thus tends to homogenize shoals.

Overview

An aggregation of fish is the general term for any collection of fish that have gathered together in some locality. Fish aggregations can be structured or unstructured. An unstructured aggregation might be a group of mixed species and sizes that have gathered randomly near some local resource, such as food or nesting sites.

If, in addition, the aggregation comes together in an interactive, social way, they may be said to be shoaling.[1][lower-alpha 1] Although shoaling fish can relate to each other in a loose way, with each fish swimming and foraging somewhat independently, they are nonetheless aware of the other members of the group as shown by the way they adjust behaviour such as swimming, so as to remain close to the other fish in the group. Shoaling groups can include fish of disparate sizes and can include mixed-species subgroups.

If the shoal becomes more tightly organised, with the fish synchronising their swimming so they all move at the same speed and in the same direction, then the fish may be said to be schooling.[1][3][lower-alpha 2] Schooling fish are usually of the same species and the same age/size. Fish schools move with the individual members precisely spaced from each other. The schools undertake complicated manoeuvres, as though the schools have minds of their own.[4]

The intricacies of schooling are far from fully understood, especially the swimming and feeding energetics. Many hypotheses to explain the function of schooling have been suggested, such as better orientation, synchronized hunting, predator confusion and reduced risk of being found. Schooling also has disadvantages, such as excretion buildup in the breathing media and oxygen and food depletion. The way the fish array in the school probably gives energy saving advantages, though this is controversial.[5]

Fish can be obligate or facultative shoalers.[6] Obligate shoalers, such as tunas, herrings and anchovy, spend all of their time shoaling or schooling, and become agitated if separated from the group. Facultative shoalers, such as Atlantic cod, saiths and some carangids, shoal only some of the time, perhaps for reproductive purposes.[7]

Shoaling fish can shift into a disciplined and coordinated school, then shift back to an amorphous shoal within seconds. Such shifts are triggered by changes of activity from feeding, resting, travelling or avoiding predators.[4]

When schooling fish stop to feed, they break ranks and become shoals. Shoals are more vulnerable to predator attack. The shape a shoal or school takes depends on the type of fish and what the fish are doing. Schools that are travelling can form long thin lines, or squares or ovals or amoeboid shapes. Fast moving schools usually form a wedge shape, while shoals that are feeding tend to become circular.[4]

Forage fish are small fish which are preyed on by larger predators for food. Predators include other larger fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Typical ocean forage fish are small, filter-feeding fish such as herring, anchovies and menhaden. Forage fish compensate for their small size by forming schools. Some swim in synchronised grids with their mouths open so they can efficiently filter feed on plankton.[8] These schools can become huge, moving along coastlines and migrating across open oceans. The shoals are concentrated food resources for the great marine predators.

These sometimes immense gatherings fuel the ocean food web. Most forage fish are pelagic fish, which means they form their schools in open water, and not on or near the bottom (demersal fish). Forage fish are short-lived, and go mostly unnoticed by humans. The predators are keenly focused on the shoals, acutely aware of their numbers and whereabouts, and make migrations themselves, often in schools of their own, that can span thousands of miles to connect with, or stay connected with them.[9]

Herring are among the more spectacular schooling fish. They aggregate together in huge numbers. The largest schools are often formed during migrations by merging with smaller schools. "Chains" of schools one hundred kilometres long have been observed of mullet migrating in the Caspian Sea. Radakov estimated herring schools in the North Atlantic can occupy up to 4.8 cubic kilometres with fish densities between 0.5 and 1.0 fish/cubic metre, totalling about three billion fish in a single school.[10] These schools move along coastlines and traverse the open oceans. Herring schools in general have very precise arrangements which allow the school to maintain relatively constant cruising speeds. Herrings have excellent hearing, and their schools react very rapidly to a predator. The herrings keep a certain distance from a moving scuba diver or a cruising predator like a killer whale, forming a vacuole which looks like a doughnut from a spotter plane.[11]

Many species of large predatory fish also school, including many highly migratory fish, such as tuna and some oceangoing sharks. Cetaceans such as dolphins, porpoises and whales, operate in organised social groups called pods.

"Shoaling behaviour is generally described as a trade-off between the anti-predator benefits of living in groups and the costs of increased foraging competition."[12] Landa (1998) argues that the cumulative advantages of shoaling, as elaborated below, are strong selective inducements for fish to join shoals.[13] Parrish et al. (2002) argue similarly that schooling is a classic example of emergence, where there are properties that are possessed by the school but not by the individual fish. Emergent properties give an evolutionary advantage to members of the school which non members do not receive.[14]

Social interaction

Support for the social and genetic function of aggregations, especially those formed by fish, can be seen in several aspects of their behaviour. For instance, experiments have shown that individual fish removed from a school will have a higher respiratory rate than those found in the school. This effect has been attributed to stress, and the effect of being with conspecifics therefore appears to be a calming one and a powerful social motivation for remaining in an aggregation.[15] Herring, for instance, will become very agitated if they are isolated from conspecifics.[7] Because of their adaptation to schooling behaviour they are rarely displayed in aquaria. Even with the best facilities aquaria can offer they become fragile and sluggish compared to their quivering energy in wild schools.

Foraging advantages

It has also been proposed that swimming in groups enhances foraging success. This ability was demonstrated by Pitcher and others in their study of foraging behaviour in shoaling cyprinids.[16] In this study, the time it took for groups of minnows and goldfish to find a patch of food was quantified. The number of fishes in the groups was varied, and a statistically significant decrease in the amount of time necessary for larger groups to find food was established. Further support for an enhanced foraging capability of schools is seen in the structure of schools of predatory fish. Partridge and others analysed the school structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna from aerial photographs and found that the school assumed a parabolic shape, a fact that was suggestive of cooperative hunting in this species.[17]

"The reason for this is the presence of many eyes searching for the food. Fish in shoals "share" information by monitoring each other's behaviour closely. Feeding behaviour in one fish quickly stimulates food-searching behaviour in others.[18]

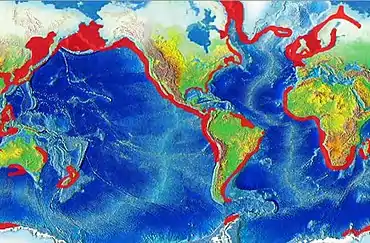

Fertile feeding grounds for forage fish are provided by ocean upwellings. Oceanic gyres are large-scale ocean currents caused by the Coriolis effect. Wind-driven surface currents interact with these gyres and the underwater topography, such as seamounts, fishing banks, and the edge of continental shelves, to produce downwellings and upwellings.[19] These can transport nutrients which plankton thrive on. The result can be rich feeding grounds attractive to the plankton feeding forage fish. In turn, the forage fish themselves become a feeding ground for larger predator fish. Most upwellings are coastal, and many of them support some of the most productive fisheries in the world. Regions of notable upwelling include coastal Peru, Chile, Arabian Sea, western South Africa, eastern New Zealand and the California coast.

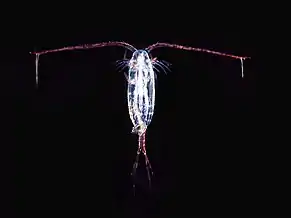

Copepods, the primary zooplankton, are a major item on the forage fish menu. They are a group of small crustaceans found in ocean and freshwater habitats. Copepods are typically one millimetre (0.04 in) to two millimetres (0.08 in) long, with a teardrop shaped body. Some scientists say they form the largest animal biomass on the planet.[20] Copepods are very alert and evasive. They have large antennae (see photo below left). When they spread their antennae they can sense the pressure wave from an approaching fish and jump with great speed over a few centimeters. If copepod concentrations reach high levels, schooling herrings adopt a method called ram feeding. In the photo below, herring ram feed on a school of copepods. They swim with their mouth wide open and their opercula fully expanded.

This copepod has its antenna spread (click to enlarge). The antenna detects the pressure wave of an approaching fish.

This copepod has its antenna spread (click to enlarge). The antenna detects the pressure wave of an approaching fish. Copepods are a major food source for forage fish like this Atlantic herring.

Copepods are a major food source for forage fish like this Atlantic herring. School of herrings ram-feeding on a school of copepods, with opercula expanded so their red gills are visible

School of herrings ram-feeding on a school of copepods, with opercula expanded so their red gills are visible Animation showing how herrings hunting in a synchronised way can capture the very alert and evasive copepod

Animation showing how herrings hunting in a synchronised way can capture the very alert and evasive copepod

The fish swim in a grid where the distance between them is the same as the jump length of their prey, as indicated in the animation above right. In the animation, juvenile herring hunt the copepods in this synchronised way. The copepods sense with their antennae the pressure-wave of an approaching herring and react with a fast escape jump. The length of the jump is fairly constant. The fish align themselves in a grid with this characteristic jump length. A copepod can dart about 80 times before it tires. After a jump, it takes it 60 milliseconds to spread its antennae again, and this time delay becomes its undoing, as the almost endless stream of herrings allows a herring to eventually snap the copepod. A single juvenile herring could never catch a large copepod.[8]

Reproductive advantages

A third proposed benefit of fish groups is that they serve a reproductive function. They provide increased access to potential mates, since finding a mate in a shoal does not take much energy. And for migrating fish that navigate long distances to spawn, it is likely that the navigation of the shoal, with an input from all the shoal members, will be better than that taken by an individual fish.[4]

Forage fish often make great migrations between their spawning, feeding and nursery grounds. Schools of a particular stock usually travel in a triangle between these grounds. For example, one stock of herrings have their spawning ground in southern Norway, their feeding ground in Iceland, and their nursery ground in northern Norway. Wide triangular journeys such as these may be important because forage fish, when feeding, cannot distinguish their own offspring.

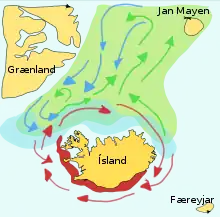

Capelin are a forage fish of the smelt family found in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans. In summer, they graze on dense swarms of plankton at the edge of the ice shelf. Larger capelin also eat krill and other crustaceans. The capelin move inshore in large schools to spawn and migrate in spring and summer to feed in plankton rich areas between Iceland, Greenland, and Jan Mayen. The migration is affected by ocean currents. Around Iceland maturing capelin make large northward feeding migrations in spring and summer. The return migration takes place in September to November. The spawning migration starts north of Iceland in December or January.

The diagram on the right shows the main spawning grounds and larval drift routes. Capelin on the way to feeding grounds is coloured green, capelin on the way back is blue, and the breeding grounds are red.

Hydrodynamic efficiency

This theory states that groups of fish may save energy when swimming together, much in the way that bicyclists may draft one another in a peloton. Geese flying in a Vee formation are also thought to save energy by flying in the updraft of the wingtip vortex generated by the previous animal in the formation.[21][22] Increased efficiencies in swimming in groups have been proposed for schools of fish and Antarctic krill.

It would seem reasonable to think that the regular spacing and size uniformity of fish in schools would result in hydrodynamic efficiencies.[12] Laboratory experiments have failed to find any gains from the hydrodynamic lift created by the neighbours of a fish in a school,[18] though it is thought that efficiency gains do occur in the wild. Landa (1998) argues that the leader of a school constantly changes, because while being in the body of a school gives a hydrodynamic advantage, the leader will be the first to the food.[13]

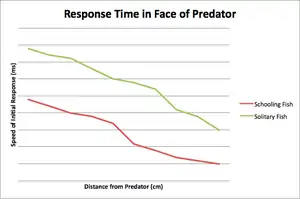

Predator avoidance

It is commonly observed that schooling fish are particularly in danger of being eaten if they are separated from the school.[4] Several anti-predator functions of fish schools have been proposed.

One potential method by which fish schools might thwart predators is the "predator confusion effect" proposed and demonstrated by Milinski and Heller (1978).[25] This theory is based on the idea that it becomes difficult for predators to choose individual prey from groups because the many moving targets create a sensory overload of the predator's visual channel. Milinski and Heller's findings have been corroborated both in experiment[26][27] and computer simulations.[28][29] "Shoaling fish are the same size and silvery, so it is difficult for a visually oriented predator to pick an individual out of a mass of twisting, flashing fish and then have enough time to grab its prey before it disappears into the shoal."[4]

Schooling behaviour confuses the lateral line organ (LLO) as well as the electrosensory system (ESS) of predators.[30][31][32] Fin movements of a single fish act as a point-shaped wave source, emitting a gradient by which predators might localize it. Since fields of many fish will overlap, schooling should obscure this gradient, perhaps mimicking pressure waves of a larger animal, and more likely confuse the lateral line perception.[30] The LLO is essential in the final stages of a predator attack.[33] Electro-receptive animals may localize a field source by using spatial non-uniformities. To produce separate signals, individual prey must be about five body widths apart. If objects are too close together to be distinguished, they will form a blurred image.[34] Based on this it was suggested that schooling may confuse the ESS of predators[30]

A third potential anti-predator effect of animal aggregations is the "many eyes" hypothesis. This theory states that as the size of the group increases, the task of scanning the environment for predators can be spread out over many individuals. Not only does this mass collaboration presumably provide a higher level of vigilance, it could also allow more time for individual feeding.[35][36]

A fourth hypothesis for an anti-predatory effect of fish schools is the "encounter dilution" effect. The dilution effect is an elaboration of safety in numbers, and interacts with the confusion effect.[18] A given predator attack will eat a smaller proportion of a large shoal than a small shoal.[37] Hamilton proposed that animals aggregate because of a "selfish" avoidance of a predator and was thus a form of cover-seeking.[38] Another formulation of the theory was given by Turner and Pitcher and was viewed as a combination of detection and attack probabilities.[39] In the detection component of the theory, it was suggested that potential prey might benefit by living together since a predator is less likely to chance upon a single group than a scattered distribution. In the attack component, it was thought that an attacking predator is less likely to eat a particular fish when a greater number of fish are present. In sum, a fish has an advantage if it is in the larger of two groups, assuming that the probability of detection and attack does not increase disproportionately with the size of the group.[40]

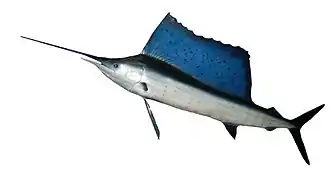

Schooling forage fish are subject to constant attacks by predators. An example is the attacks that take place during the African sardine run. The African sardine run is a spectacular migration by millions of silvery sardines along the southern coastline of Africa. In terms of biomass, the sardine run could rival East Africa's great wildebeest migration.[41] Sardines have a short life-cycle, living only two or three years. Adult sardines, about two years old, mass on the Agulhas Bank where they spawn during spring and summer, releasing tens of thousands of eggs into the water. The adult sardines then make their way in hundreds of shoals towards the sub-tropical waters of the Indian Ocean. A larger shoal might be 7 kilometres (4 mi) long, 1.5 kilometres (1 mi) wide and 30 meters (100 ft) deep. Huge numbers of sharks, dolphins, tuna, sailfish, Cape fur seals and even killer whales congregate and follow the shoals, creating a feeding frenzy along the coastline.[42]

When threatened, sardines (and other forage fish) instinctively group together and create massive bait balls. Bait balls can be up to 20 meters (70 ft) in diameter. They are short lived, seldom lasting longer than 20 minutes. The fish eggs, left behind at the Agulhas Banks, drift north west with the current into waters off the west coast, where the larvae develop into juvenile fish. When they are old enough, they aggregate into dense shoals and migrate southwards, returning to the Agulhas banks to restart the cycle.[42]

The development of schooling behavior was probably associated with an increased quality of perception, predatory lifestyle and size sorting mechanisms to avoid cannibalism.[32] In filter-feeding ancestors, before vision and the octavolateralis system (OLS) had developed, the risk of predation would have been limited and mainly due to invertebrate predators. Hence, at that time, safety in numbers was probably not a major incentive for gathering in shoals or schools. The development of vison and the OLS would have permitted detection of potential prey. This could have led to an increased potential for cannibalism within the shoal. On the other hand, increased quality of perception would give small individuals a chance to escape or to never join a shoal with larger fish. It has been shown that small fish avoid joining a group with larger fish, although big fish do not avoid joining small conspecifics.[43] This sorting mechanism based on increased quality of perception could have resulted in homogeneity of size of fish in shoals, which would increase the capacity for moving in synchrony.[32]

Predator countermeasures

.JPG.webp)

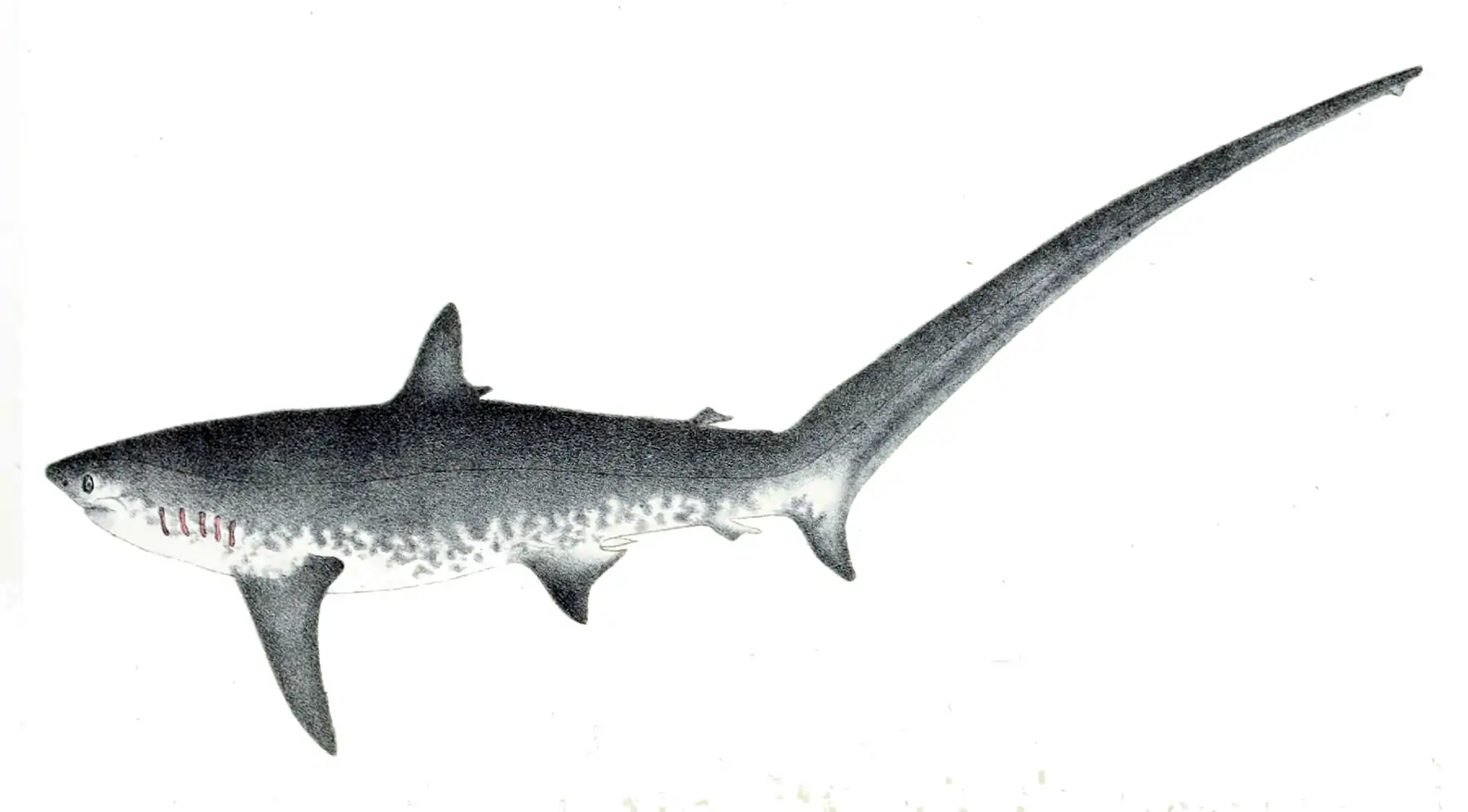

Predators have devised various countermeasures to undermine the defensive shoaling and schooling manoeuvres of forage fish. The sailfish raises its sail to make it appear much larger so it can herd a school of fish or squid. Swordfish charge at high speed through forage fish schools, slashing with their swords to kill or stun prey. They then turn and return to consume their "catch". Thresher sharks use their long tails to stun shoaling fishes. Before striking, the sharks compact schools of prey by swimming around them and splashing the water with its tail, often in pairs or small groups. Threshers swim in circles to drive schooling prey into a compact mass, before striking them sharply with the upper lobe of its tail to stun them.[44][45] Spinner sharks charge vertically through the school, spinning on their axis with their mouths open and snapping all around. The shark's momentum at the end of these spiralling runs often carries it into the air.[46][47]

Sailfish herd with their sails.

Sailfish herd with their sails. Swordfish slash with their swords.

Swordfish slash with their swords. Thresher shark strike with their tails.

Thresher shark strike with their tails. Spinner shark spin on their axis.

Spinner shark spin on their axis.

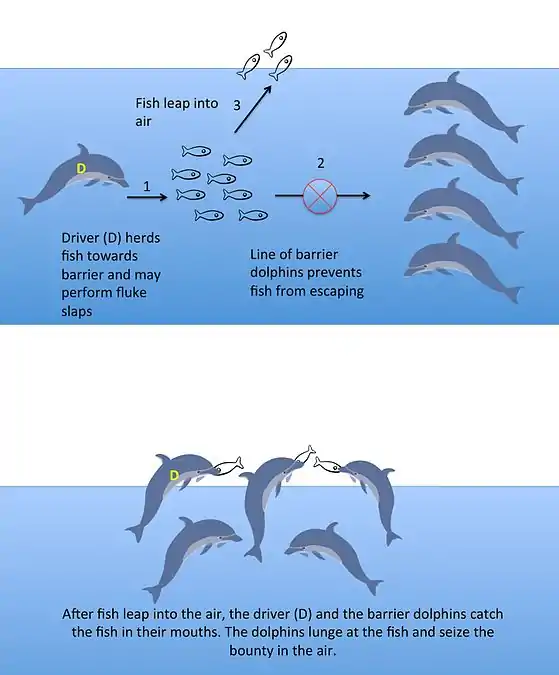

↑ A team of common bottlenose dolphins cooperate to make schooling fish jump in the air. In this vulnerable position the fish are easy prey for the dolphins.[48]

↑ A team of common bottlenose dolphins cooperate to make schooling fish jump in the air. In this vulnerable position the fish are easy prey for the dolphins.[48]

Some predators, such as dolphins, hunt in groups of their own. One technique employed by many dolphin species is herding, where a pod will control a school of fish while individual members take turns ploughing through and feeding on the more tightly-packed school (a formation commonly known as a bait ball). Corralling is a method where fish are chased to shallow water where they are more easily captured. In South Carolina, the Atlantic bottlenose dolphin takes this one step further with what has become known as strand feeding, where the fish are driven onto mud banks and retrieved from there.[49]

Common bottlenose dolphins have been observed using another technique. One dolphin acts as a "driver" and herds a school of fish towards several other dolphins who form a barrier. The driver dolphin slaps its fluke which makes the fish leap into the air. As the fish leap, the driver dolphin moves with the barrier dolphins and catches the fish in the air.[48] This type of cooperative role specialization seems to be more common in marine animals than in terrestrial animals, perhaps because the oceans have more variability in prey diversity, biomass, and predator mobility.[48]

During the sardine run, as many as 18,000 dolphins, behaving like sheepdogs, herd the sardines into bait balls, or corral them in shallow water. Once rounded up, the dolphins and other predators take turns ploughing through the bait balls, gorging on the fish as they sweep through. Seabirds also attack them from above, flocks of gannets, cormorants, terns and gulls. Some of these seabirds plummet from heights of 30 metres (100 feet), plunging through the water leaving vapour-like trails, similar to that of fighter planes.[42] Gannets plunge into the water at up to 100 kilometres per hour (60 mph). They have air sacs under their skin in their face and chest which act like bubble-wrap, cushioning the impact with the water.

Subsets of bottlenose dolphin populations in Mauritania are known to engage in interspecific cooperative fishing with human fishermen. The dolphins drive a school of fish towards the shore where humans await with their nets. In the confusion of casting nets, the dolphins catch a large number of fish as well. Intraspecific cooperative foraging techniques have also been observed, and some propose that these behaviours are transmitted through cultural means. Rendell & Whitehead have proposed a structure for the study of culture in cetaceans,[50]

Some whales lunge feed on bait balls.[51] Lunge feeding is an extreme feeding method, in which the whale accelerates from below a bait ball to a high velocity and then opens its mouth to a large gape angle. This generates the water pressure required to expand its mouth and engulf and filter a huge amount of water and fish. Lunge feeding by the huge rorquals is said to be the largest biomechanical event on Earth.[52]

| External video | |

|---|---|

A pair of humpback whales, a species of rorqual, lunge feeding

A pair of humpback whales, a species of rorqual, lunge feeding Gannets "divebomb" at high speed

Gannets "divebomb" at high speed

How fish school

Fish schools swim in disciplined phalanxes, with some species, such as herrings, able to stream up and down at impressive speeds, twisting this way and that, and making startling changes in the shape of the school, without collisions. It is as if their motions are choreographed, though they are not. There must be very fast response systems to allow the fish to do this. Young fish practice schooling techniques in pairs, and then in larger groups as their techniques and senses mature. The schooling behaviour develops instinctively and is not learnt from older fish. To school the way they do, fish require sensory systems which can respond with great speed to small changes in their position relative to their neighbour. Most schools lose their schooling abilities after dark, and just shoal. This indicates that vision is important to schooling. The importance of vision is also indicated by the behaviour of fish who have been temporarily blinded. Schooling species have eyes on the sides of their heads, which means they can easily see their neighbours. Also, schooling species often have "schooling marks" on their shoulders or the base of their tails, or visually prominent stripes, which provide reference marks when schooling,[53] similar in function to passive markers in artificial motion capture. However fish without these markers will still engage in schooling behaviour,[54] though perhaps not as efficiently.

Other senses are also used. Pheromones or sound may also play a part but supporting evidence has not been found so far. The lateral line is a line running along each side of the fish from the gill covers to the base of the tail. In laboratory experiments the lateral lines of schooling fish have been removed. They swam closer, leading to a theory that the lateral lines provide additional stimuli input when the fish get too close.[53] The lateral-line system is very sensitive to changes in water currents and vibration in the water. It uses receptors called neuromasts, each of which is composed of a group of hair cells. The hairs are surrounded by a protruding jelly-like cupula, typically 0.1 to 0.2 mm long. The hair cells in the lateral line are similar to the hair cells inside the vertebrate inner ear, indicating that the lateral line and the inner ear share a common origin.[4]

Describing shoal structure

It is difficult to observe and describe the three dimensional structure of real world fish shoals because of the large number of fish involved. Techniques include the use of recent advances in fisheries acoustics.[55]

Parameters defining a fish shoal include:

- Shoal size – The number of fish in the shoal. A remote sensing technique has been used near the edge of the continental shelf off the east coast of North America to take images of fish shoals. The shoals – most likely made up of Atlantic herring, scup, hake, and black sea bass – were said to contain “tens of millions” of fish and stretched for “many kilometers”.[56]

- Density – The density of a fish shoal is the number of fish divided by the volume occupied by the shoal. Density is not necessarily a constant throughout the group. Fish in schools typically have a density of about one fish per cube of body length.[57]

.jpg.webp) Low density

Low density High density

High density Low polarity

Low polarity High polarity

High polarity

- Polarity – The group polarity describes the extent to which the fish are all pointing in the same direction. In order to determine this parameter, the average orientation of all animals in the group is determined. For each animal, the angular difference between its orientation and the group orientation is then found. The group polarity is the average of these differences.[58]

- Nearest neighbour distance – The nearest neighbour distance (NND) describes the distance between the centroid of one fish (the focal fish) and the centroid of the fish nearest to the focal fish. This parameter can be found for each fish in an aggregation and then averaged. Care must be taken to account for the fish located at the edge of a fish aggregation, since these fish have no neighbour in one direction. The NND is also related to the packing density. For schooling fish the NND is usually between one-half and one body length.

- Nearest neighbour position – In a polar coordinate system, the nearest neighbour position describes the angle and distance of the nearest neighbour to a focal fish.

- Packing fraction – The packing fraction is a parameter borrowed from physics to define the organization (or state i.e. solid, liquid, or gas) of 3D fish groups. It is an alternative measure to density. In this parameter, the aggregation is idealized as an ensemble of solid spheres, with each fish at the center of a sphere. The packing fraction is defined as the ratio of the total volume occupied by all individual spheres divided by the global volume of the aggregation. Values range from zero to one, where a small packing fraction represents a dilute system like a gas.[59]

- Integrated conditional density – This parameter measures the density at various length scales and therefore describes the homogeneity of density throughout an animal group.[59]

- Pair distribution function – This parameter is usually used in physics to characterize the degree of spatial order in a system of particles. It also describes the density, but this measure describes the density at a distance away from a given point. Cavagna et al. found that flocks of starlings exhibited more structure than a gas but less than a liquid.[59]

Modelling school behaviour

![]() Boids simulation – needs Java

Boids simulation – needs Java

Mathematical models

The observational approach is complemented by the mathematical modelling of schools. The most common mathematical models of schools instruct the individual animals to follow three rules:

- Move in the same direction as your neighbour

- Remain close to your neighbours

- Avoid collisions with your neighbours

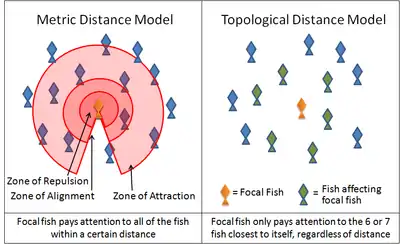

An example of such a simulation is the boids program created by Craig Reynolds in 1986.[61] Another is the self-propelled particle model introduced by Vicsek et al. in 1995[62] Many current models use variations on these rules. For instance, many models implement these three rules through layered zones around each fish.

- In the zone of repulsion very close to the fish, the focal fish will seek to distance itself from its neighbours in order to avoid a collision.

- In the slightly further away zone of alignment, a focal fish will seek to align its direction of motion with its neighbours.

- In the outmost zone of attraction, which extends as far away from the focal fish as it is able to sense, the focal fish will seek to move towards a neighbour.

The shape of these zones will necessarily be affected by the sensory capabilities of the fish. Fish rely on both vision and on hydrodynamic signals relayed through its lateral line. Antarctic krill rely on vision and on hydrodynamic signals relayed through its antennae.

In a masters thesis published in 2008, Moshi Charnell produced schooling behaviour without using the alignment matching component of an individuals behaviour.[63] His model reduces the three basic rules to the following two rules:

- Remain close to your neighbours

- Avoid collisions with your neighbours

In a paper published in 2009, researchers from Iceland recount their application of an interacting particle model to the capelin stock around Iceland, successfully predicting the spawning migration route for 2008.[64]

Evolutionary models

In order to gain insight into why animals evolve swarming behaviour, scientists have turned to evolutionary models that simulate populations of evolving animals. Typically these studies use a genetic algorithm to simulate evolution over many generations in the model. These studies have investigated a number of hypotheses explaining why animals evolve swarming behaviour, such as the selfish herd theory,[65][66][67][68] the predator confusion effect,[29][69] the dilution effect,[70][71] and the many eyes theory.[72]

Mapping the formation of schools

In 2009, building on recent advances in acoustic imaging,[55][73] a group of MIT researchers observed for "the first time the formation and subsequent migration of a huge shoal of fish."[74] The results provide the first field confirmation of general theories about how large groups behave, from locust swarms to bird flocks.[75]

The researchers imaged spawning Atlantic herring off Georges Bank. They found that the fish come together from deeper water in the evening, shoaling in a disordered way. A chain reaction triggers when the population density reaches a critical value, like an audience wave travelling around a sport stadium. A rapid transition then occurs, and the fish become highly polarised and synchronized in the manner of schooling fish. After the transition, the schools start migrating, extending up to 40 kilometres (25 mi) across the ocean, to shallow parts of the bank. There they spawn during the night. In the morning, the fish school back to deeper water again and then disband. Small groups of leaders were also discovered that significantly influenced much larger groups.[75]

Leadership and decision-making

Fish schools are faced with decisions they must make if they are to remain together. For example, a decision might be which direction to swim when confronted by a predator, which areas to stop and forage, or when and where to migrate.[76]

Quorum sensing can function as a collective decision-making process in any decentralised system. A quorum response has been defined as "a steep increase in the probability of group members performing a given behaviour once a threshold minimum number of their group mates already performing that behaviour is exceeded".[77] A recent investigation showed that small groups of fish used consensus decision-making when deciding which fish model to follow. The fish did this by a simple quorum rule such that individuals watched the decisions of others before making their own decisions. This technique generally resulted in the 'correct' decision but occasionally cascaded into the 'incorrect' decision. In addition, as the group size increased, the fish made more accurate decisions in following the more attractive fish model.[78] Consensus decision-making, a form of collective intelligence, thus effectively uses information from multiple sources to generally reach the correct conclusion. Such behaviour has also been demonstrated in the shoaling behaviour of threespine sticklebacks.[77]

Other open questions of shoaling behaviour include identifying which individuals are responsible for the direction of shoal movement. In the case of migratory movement, most members of a shoal seem to know where they are going. Observations on the foraging behaviour of captive golden shiner (a kind of minnow) found they formed shoals which were led by a small number of experienced individuals who knew when and where food was available.[79] If all golden shiners in a shoal have similar knowledge of food availability, there are a few individuals that still emerge as natural leaders (being at the front more often) and behavioural tests suggest they are naturally bolder.[80] Smaller golden shiners appear more willing than larger ones to be near the front of the shoal, perhaps because they are hungrier.[81] Observations on the common roach have shown that food-deprived individuals tend to be at the front of a shoal, where they obtain more food[82][83] but where they may also be more vulnerable to ambush predators.[84] Individuals that are wary of predation tend to seek more central positions within shoals.[85]

Shoal choice

Experimental studies of shoal preference are relatively easy to perform. An aquarium containing a choosing fish is sandwiched between two aquaria containing different shoals, and the choosing fish is assumed to spend more time next to the shoal it prefers. Studies of this kind have identified several factors important for shoal preference.

Fish generally prefer larger shoals.[86][87] This makes sense, as larger shoal usually provide better protection against predators. Indeed, the preference for larger shoals seems stronger when predators are nearby,[88][89] or in species that rely more on shoaling than body armour against predation.[90] Larger shoals may also find food faster, though that food would have to be shared amongst more individuals. Competition may mean that hungry individuals might prefer smaller shoals or exhibit a lesser preference for very large shoals, as shown in sticklebacks.[91][92]

Fish prefer to shoal with their own species. Sometimes, several species may become mingled in one shoal, but when a predator is presented to such shoals, the fish reorganize themselves so that each individual ends up being closer to members of its own species.[93]

Fish tend to prefer shoals made up of individuals that match their own size.[94][95][96] This makes sense as predators have an easier time catching individuals that stand out in a shoal. Some fish may even prefer shoals of another species if this means a better match in current body size.[97] As for shoal size however, hunger can affect the preference for similarly-sized fish; large fish, for example, might prefer to associate with smaller ones because of the competitive advantage they will gain over these shoalmates. In golden shiner, large satiated fish prefer to associate with other large individuals, but hungry ones prefer smaller shoalmates.[98]

Fish prefer to shoal with individuals with which the choosing fish is already familiar. This has been demonstrated in guppies,[99][100] threespine stickleback,[101] banded killifish,[102] the surfperch Embiotoca jacksoni,[103] Mexican tetra,[104] and various minnows.[105][106] A study with the White Cloud Mountain minnow has also found that choosing fish prefer to shoal with individuals that have consumed the same diet as themselves.[107]

Sticklebacks and killifish have been shown to prefer shoals made up of healthy individuals over parasitized ones, on the basis of visual signs of parasitism and abnormal behaviour by the parasitized fish.[108][109][110][111] Zebrafish prefer shoals that consist of well-fed (greater stomach width) fish over food-deprived ones.[112]

Threespine stickleback prefer to join a shoal made up of bold individuals rather than shy ones.[113] Angelfish prefer shoals made up of subordinate rather than dominant individuals.[114] European minnow can discriminate between shoals composed of good versus poor competitors, even in the absence of obvious cues such as differences in aggressiveness, size, or feeding rate; they prefer to associate with the poor competitors.[115] All of this suggests a strategy to obtain food, as bolder individuals should be more likely to find food, while subordinates would offer less competition for the discovered food.

Fish prefer to join shoals that are actively feeding.[116][117] Golden shiner can also detect the anticipatory activity of shoals that expect to be fed soon, and preferentially join such shoals.[118] Zebrafish also choose shoals that are more active.[119]

Commercial fishing

The schooling behaviour of fish is exploited on an industrial scale by the commercial fishing industry. Huge purse seiner vessels use spotter planes to locate schooling fish, such as tuna, cod, mackerel and forage fish. They can capture huge schools by rapidly encircling them with purse seine nets with the help of fast auxiliary boats and sophisticated sonar, which can track the shape of the shoal.

Further examples

Blacksmith fish live in loose shoals. They have a symbiotic relationship with the parasite eating senorita fish. When they encounter a shoal of senorita fish, they stop and form a tight ball and hang upside down (pictured), each fish waiting its turn to be cleaned. The senorita fish pick dead tissues and external parasites, like parasitic copecods and isocods, from the skin of other fishes.

Some shoals engage in mobbing behaviour. For example, bluegills form large nesting colonies and sometimes attack snapping turtles. This may function to advertise their presence, drive the predator from the area, or aid in cultural transmission of predator recognition.[120]

Piranha have a reputation as fearless fish that hunt in ferocious packs. However, recent research, which "started off with the premise that they school as a means of cooperative hunting", discovered that they were in fact rather fearful fish, like other fish, which schooled for protection from their predators, such as cormorants, caimans and dolphins. Piranhas are "basically like regular fish with large teeth".[121]

Humboldt squid are large carnivorous marine invertebrates that move in schools of up to 1,200 individuals. They swim at speeds of up to 24 kilometres per hour (15 mph or 13 kn) propelled by water ejected through a siphon and by two triangular fins. Their tentacles bear suckers lined with sharp teeth with which they grasp prey and drag it towards a large, sharp beak. During the day the Humboldt squid behave similar to mesopelagic fish, living at depths of 200 to 700 m (660 to 2,300 ft). Electronic tagging has shown that they also undergo diel vertical migrations which bring them closer to the surface from dusk to dawn.[122] They hunt near the surface at night, taking advantage of the dark to use their keen vision to feed on more plentiful prey. The squid feed primarily on small fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, and copepod, and hunt for their prey in a cooperative fashion, the first observation of such behaviour in invertebrates.[123] The Humboldt squid is also known to quickly devour larger prey when cooperatively hunting in groups. Humboldt squid are known for their speed in feasting on hooked fish, sharks, and squid, even from their own species and shoal,[124] and have been known to attack fishermen and divers.[125]

See also

Notes

- Other collective nouns used for fish include a draught of fish, a drift of fish, or a scale of fish. Collective nouns used for specific fish or marine animal species groups include a grind of blackfish, a troubling of goldfish, glean of herrings, bind or run of salmon, shiver of sharks, fever of stingrays, taint of tilapia, hover of trouts and pod of whales.

- Shoaling is a special case of aggregating, and schooling is a special case of shoaling. While schooling and shoaling mean different things within biology, they are often treated as synonyms by non-specialists, with speakers of British English tending to use "shoaling" to describe any grouping of fish, while speakers of American English tend to use "schooling" just as loosely.[1]

References

- Pitcher and Parish 1993, page 365.

- Shaw, E (1978). "Schooling fishes". American Scientist. 66 (2): 166–175. Bibcode:1978AmSci..66..166S.

- Helfman G., Collette B., & Facey D.: The Diversity of Fishes, Blackwell Publishing, p 375, 1997, ISBN 0-86542-256-7

- Moyle, PB and Cech, JJ (2003) Fishes, An Introduction to Ichthyology. 5th Ed, Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-13-100847-2

- Pitcher, TJ and Parrish, JK (1993) Behaviour of Teleost Fishes, Chp 12: Functions of shoaling behaviour in teleosts Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-42930-9

- Breder, C. M., Jr. (1967). "On the survival value of fish schools". Zoologica. 52: 25–40.

- Partridge, B.; Pitcher, T.; Cullen, M.; Wilson, J. (1980). "The three-dimensional structure of fish schools". Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 6 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1007/BF00292770. S2CID 8032766.

- Kils, U. (1992). "The ecoSCOPE and dynIMAGE: Microscale tools for in situ studies of predator-prey interactions". Arch Hydrobiol Beih. 36: 83–96.

- National Coalition for Marine Conservation: Forage fish

- Radakov DV (1973) Schooling in the ecology of fish. Israel Program for Scientific Translation, translated by Mill H. Halsted Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-7065-1351-6

- Nøttestad, L.; Axelsen, B. E. (1999). "Herring schooling manoeuvres in response to killer whale attacks" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 77 (10): 1540–1546. doi:10.1139/z99-124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- Hoare, D. J.; Krause, J.; Peuhkuri, N.; Godin, J. G. J. (2000). "Body size and shoaling in fish". Journal of Fish Biology. 57 (6): 1351–1366. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2000.tb02217.x.

- Landa, J. T. (1998). "Bioeconomics of schooling fishes: selfish fish, quasi-free riders, and other fishy tales". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 53 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1023/A:1007414603324. S2CID 12674762.

- Parrish, J. K.; Viscedo, S. C.; Grunbaum, D. (2002). "Self organised fish-schools: An examination of emergent properties". Biological Bulletin. 202 (3): 296–305. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.116.1548. doi:10.2307/1543482. JSTOR 1543482. PMID 12087003. S2CID 377484.

- Abrahams, M.; Colgan, P. (1985). "Risk of predation, hydrodynamic efficiency, and their influence on school structure". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 13 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1007/BF00000931. S2CID 22329892.

- Pitcher, T.; Magurran, A.; Winfield, I. (1982). "Fish in larger shoals find food faster". Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 10 (2): 149–151. doi:10.1007/BF00300175. S2CID 6340986.

- Partridge, B.; Johansson, J.; Kalish, J. (1983). "The structure of schools of giant bluefin tuna in Cape Cod Bay". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 9 (3–4): 253–262. doi:10.1007/BF00692374. S2CID 6799134.

- Pitcher and Parish 1993

- "Wind Driven Surface Currents: Upwelling and Downwelling".

- Biology of Copepods Archived 2009-01-01 at the Wayback Machine at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg

- Fish, F. E. (1995). "Kinematics of ducklings swimming in formation: consequences of position". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 273 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/jez.1402730102. S2CID 49732151.

- Alexander, R McNeill (2004). "Hitching a lift hydrodynamically - in swimming, flying and cycling". Journal of Biology. 3 (2): 7. doi:10.1186/jbiol5. PMC 416560. PMID 15132738.

- Aparna, Bhaduri (2011) Mockingbird Tales: Readings in Animal Behavior OpenStax College.

- Hoare, D. J.; Couzin, I. D.; Godin, J. G.; Krause, J. (2004). "Context-dependent group size choice in fish". Animal Behaviour. 67 (1): 155–164. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.004. S2CID 2244463.

- Milinski, H.; Heller, R. (1978). "Influence of a predator on the optimal foraging behavior of sticklebacks". Nature. 275 (5681): 642–644. Bibcode:1978Natur.275..642M. doi:10.1038/275642a0. S2CID 4184043.

- Jeschke JM, Tollrian R; Tollrian, Ralph (2007). "Prey swarming: which predators become confused and why?". Animal Behaviour. 74 (3): 387–393. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.08.020. S2CID 53163951.

- Ioannou CC; Tosh CR; Neville L; Krause J (2008). "The confusion effect—from neural networks to reduced predation risk". Behavioral Ecology. 19 (1): 126–130. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm109.

- Krakauer DC (1995). "Groups confuse predators by exploiting perceptual bottlenecks: a connectionist model of the confusion effect". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 36 (6): 421–429. doi:10.1007/BF00177338. S2CID 22967420.

- Olson RS; Hintze A; Dyer FC; Knoester DB; Adami C (2013). "Predator confusion is sufficient to evolve swarming behaviour". J. R. Soc. Interface. 10 (85): 20130305. arXiv:1209.3330. doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0305. PMC 4043163. PMID 23740485.

- Larsson, M (2009). "Possible functions of the octavolateralis system in fish schooling". Fish and Fisheries. 10 (3): 344–355. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00330.x.

- Larsson, M (2011). "Incidental sounds of locomotion in animal cognition". Animal Cognition. 15 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/s10071-011-0433-2. PMC 3249174. PMID 21748447.

- Larsson, M (2012). "Why do fish school?". Current Zoology. 58 (1): 116–128. doi:10.1093/czoolo/58.1.116.

- New, JG; Fewkes, LA; Khan, AN (2001). "Strike feeding behavior in the muskellunge, Esox masquinongy: Contributions of the lateral line and visual sensory systems". J Exp Biol. 204 (6): 1207–1221. PMID 11222136.

- Babineau, D; Lewis, JE; Longtin, A (2007). "Spatial acuity and prey detection in weakly electric fish". PLOS Comput Biol. 3 (3): 402–411. Bibcode:2007PLSCB...3...38B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030038. PMC 1808493. PMID 17335346.

- Roberts, G (1996). "Why individual vigilance declines as group size increases". Anim Behav. 51 (5): 1077–1086. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.7279. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0109. S2CID 53202810.

- Lima, S (1995). "Back to the basics of anti-predatory vigilance: the group-size effect". Animal Behaviour. 49 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(95)80149-9. S2CID 53205760.

- Morse, DH (1977). "Feeding behavior and predator avoidance in heterospecific groups". BioScience. 27 (5): 332–339. doi:10.2307/1297632. JSTOR 1297632.

- Hamilton, W. D. (1971). "Geometry for the selfish herd". J. Theor Biology. 31 (2): 295–311. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(71)90189-5. PMID 5104951.

- Turner, G.; Pitcher, T. (1986). "Attack abatement: a model for group protection by combined avoidance and dilution". American Naturalist. 128 (2): 228–240. doi:10.1086/284556. S2CID 84738064.

- Krause, J.; Ruxton, G.; Rubenstein, D. (1998). "Is there always an influence of shoal size on predator hunting success?". Journal of Fish Biology. 52 (3): 494–501. doi:10.1006/jfbi.1997.0595.

- "Marine Scientists Scratch Heads Over Sardines". Archived from the original on 2004-09-25.

- "Sardine Run Shark Feeding Frenzy Phenomenon in Africa". Archived from the original on 2008-12-02.

- Lachlan, RF; Crooks, L; Laland, KN (1998). "Who follows whom? Shoaling preferences and social learning of foraging information in guppies". Animal Behaviour. 56 (1): 181–190. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0760. PMID 9710476. S2CID 30973104.

- Seitz, J.C. Pelagic Thresher. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved on December 22, 2008.

- Oliver, SP; Turner, JR; Gann, K; Silvosa, M; D'Urban Jackson, T (2013). "Thresher sharks use tail-slaps as a hunting strategy". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e67380. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...867380O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067380. PMC 3707734. PMID 23874415.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 466–468. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- "Carcharhinus brevipinna, Spinner Shark". MarineBio.org. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- Gazda, S K; Connor, R C; Edgar, R K; Cox, F (2005). "A division of labour with role specialization in group-hunting bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off Cedar Key, Florida". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 272 (1559): 135–140. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2937. PMC 1634948. PMID 15695203.

- "Coastal Stock(s) of Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin: Status Review and Management," Proceedings and Recommendations from a Workshop held in Beaufort, North Carolina, 13 September 1993 – 14 September 1993. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service. pp. 56–57.

- Rendell, L.; Whitehead, H. (2001). "Culture in whales and dolphins". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 24 (2): 309–382. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0100396X. PMID 11530544. S2CID 24052064.

- Reeves RR, Stewart BS, Clapham PJ and Powell J A (2002) National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World Chanticleer Press. ISBN 9780375411410.

- Potvin, J; Goldbogen, JA; Shadwick, R. E. (2009). "Passive versus active engulfment: verdict from trajectory simulations of lunge-feeding fin whales Balaenoptera physalus". J. R. Soc. Interface. 6 (40): 1005–1025. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0492. PMC 2827442. PMID 19158011.

- Bone Q and Moore RH (2008) Biology of Fishes pp. 418–422, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-37562-7

- BBC News Online, Robofish accepted by wild fish shoal, 09:54 GMT, Thursday, 1 July 2010 10:54 UK

- "One fish, two fish: New MIT sensor improves fish counts". Phys.org. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Makris, N.C.; Ratilal, P.; Symonds, D.T.; Jagannathan, S.; Lee, S.; Nero, R.W. (2006). "Fish Population and Behavior Revealed by Instantaneous Continental Shelf-Scale Imaging". Science. 311 (5761): 660–663. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..660M. doi:10.1126/science.1121756. PMID 16456080. S2CID 140558930.

- Pitcher, TJ; Partridge, TL (1979). "Fish School density and volume". Mar. Biol. 54 (4): 383–394. doi:10.1007/BF00395444. S2CID 84810154.

- Viscido, S.; Parrish, J.; Grunbaum, D. (2004). "Individual behavior and emergent properties of fish schools: a comparison of observation and theory" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 273: 239–249. Bibcode:2004MEPS..273..239V. doi:10.3354/meps273239.

- Cavagna, A.; Cimarelli, Giardina; Orlandi, Parisi; Procaccini, Santagati; Stefanini (2008). "New statistical tools for analyzing the structure of animal groups". Mathematical Biosciences. 214 (1–2): 32–37. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2008.05.006. PMID 18586280.

- "Self driven particle model". PhET. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Reynolds, CW (1987). "Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model". Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '87. Computer Graphics. 21. pp. 25–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.103.7187. doi:10.1145/37401.37406. ISBN 978-0897912273. S2CID 546350.

- Vicsek, T; Czirok, A; Ben-Jacob, E; Cohen, I; Shochet, O (1995). "Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles". Physical Review Letters. 75 (6): 1226–1229. arXiv:cond-mat/0611743. Bibcode:1995PhRvL..75.1226V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1226. PMID 10060237. S2CID 15918052.

- Charnell, M. (2008)"Individual-based modelling of ecological systems and social aggregations". Download

- Barbaro A, Einarsson B, Birnir B, Sigurðsson S, Valdimarsson S, Pálsson ÓK, Sveinbjörnsson S, Sigurðsson P (2009). "Modelling and simulations of the migration of pelagic fish". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 66 (5): 826–838. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp067.

- Olson RS; Knoester DB; Adami C (2013). Critical Interplay Between Density-dependent Predation and Evolution of the Selfish Herd. Proceedings of GECCO 2013. pp. 247–254. doi:10.1145/2463372.2463394. ISBN 9781450319638. S2CID 14414033.

- Ward CR; Gobet F; Kendall G (2001). "Evolving collective behavior in an artificial ecology". Artificial Life. 7 (2): 191–209. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.108.3956. doi:10.1162/106454601753139005. PMID 11580880. S2CID 12133884.

- Reluga TC, Viscido S; Viscido, Steven (2005). "Simulated evolution of selfish herd behavior". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 234 (2): 213–225. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.11.035. PMID 15757680.

- Wood AJ, Ackland GJ; Ackland, G. J (2007). "Evolving the selfish herd: emergence of distinct aggregating strategies in an individual-based model". Proc Biol Sci. 274 (1618): 1637–1642. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0306. PMC 2169279. PMID 17472913.

- Demsar J; Hemelrijk CK; Hildenbrandt H & Bajec IL (2015). "Simulating predator attacks on schools: Evolving composite tactics" (PDF). Ecological Modelling. 304: 22–33. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.02.018.

- Tosh CR (2011). "Which conditions promote negative density dependent selection on prey aggregations?" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 281 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.04.014. PMID 21540037.

- Ioannou CC; Guttal V; Couzin ID (2012). "Predatory Fish Select for Coordinated Collective Motion in Virtual Prey". Science. 337 (6099): 1212–1215. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1212I. doi:10.1126/science.1218919. PMID 22903520. S2CID 10203872.

- Olson RS; Haley PB; Dyer FC & Adami C (2015). "Exploring the evolution of a trade-off between vigilance and foraging in group-living organisms". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (9): 150135. arXiv:1408.1906. Bibcode:2015RSOS....250135O. doi:10.1098/rsos.150135. PMC 4593673. PMID 26473039.

- Makris, NC; Ratilal, P; Symonds, DT; Jagannathan, S; Lee, S; Nero, RW (2006). "Fish Population and Behavior Revealed by Instantaneous Continental Shelf-Scale Imaging". Science. 311 (5761): 660–663. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..660M. doi:10.1126/science.1121756. PMID 16456080. S2CID 140558930.

- Makris, NC; Ratilal, P; Jagannathan, S; Gong, Z; Andrews, M; Bertsatos, I; Godø, OR; Nero, RW; Jech, M; et al. (2009). "Critical Population Density Triggers Rapid Formation of Vast Oceanic Fish Shoals". Science. 323 (5922): 1734–1737. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1734M. doi:10.1126/science.1169441. PMID 19325116. S2CID 6478019.

- "Scientists IDs genesis of animal behavior patterns". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Sumpter, D. "Collective Behavior".

- Ward, AJ; Krause, J; Sumpter, DJ (2012). "Quorum decision-making in foraging fish shoals". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e32411. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732411W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032411. PMC 3296701. PMID 22412869.

- Sumpter, D.; Krause, J; James, R.; Couzin, I.; Ward, A. (2008). "Consensus decision making by fish". Current Biology. 18 (22): 1773–1777. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.064. PMID 19013067. S2CID 11362054.

- Reebs, SG (2000). "Can a minority of informed leaders determine the foraging movements of a fish shoal?". Animal Behaviour. 59 (2): 403–409. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1314. PMID 10675263. S2CID 4945309.

- Leblond, C.; Reebs, S.G. (2006). "Individual leadership and boldness in shoals of golden shiners (Notemigonus crysoleucas)". Behaviour. 143 (10): 1263–1280. doi:10.1163/156853906778691603. S2CID 56117643.

- Reebs, S.G. (2001). "Influence of body size on leadership in shoals of golden shiners, Notemigonus crysoleucas". Behaviour. 138 (7): 797–809. doi:10.1163/156853901753172656.

- Krause, J. (1993). "The relationship between foraging and shoal position in a mixed shoal of roach (Rutilus rutilus) and chub (Leuciscus leuciscus): a field study". Oecologia. 93 (3): 356–359. Bibcode:1993Oecol..93..356K. doi:10.1007/bf00317878. PMID 28313435. S2CID 13140673.

- Krause, J.; Bumann, D.; Todt, D. (1992). "Relationship between the position preference and nutritional state of individuals in schools of juvenile roach (Rutilus rutilus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 30 (3–4): 177–180. doi:10.1007/bf00166700. S2CID 32061496.

- Bumann, D.; Krause, J.; Rubenstein, D. (1997). "Mortality risk of spatial positions in animal groups: the danger of being in the front". Behaviour. 134 (13): 1063–1076. doi:10.1163/156853997x00403.

- Krause, J. (1993). "The effect of Schreckstoff on the shoaling behaviour of the minnow: a test of Hamilton's selfish herd theory". Animal Behaviour. 45 (5): 1019–1024. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1119. S2CID 54287659.

- Keenleyside, M.H.A. (1955). "Some aspects of the schooling behaviour in fish" (PDF). Behaviour. 8: 183–248. doi:10.1163/156853955x00229.

- Tedeger, R.W.; Krause, J. (1995). "Density dependence and numerosity in fright stimulated aggregation behaviour of shoaling fish". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 350 (1334): 381–390. Bibcode:1995RSPTB.350..381T. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0172.

- Hager, M.C.; Helfman, G.S. (1991). "Safety in numbers: shoal size choice by minnows under predatory threat". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (4): 271–276. doi:10.1007/bf00163984. S2CID 30901973.

- Ashley, E.J.; Kats, L.B.; Wolfe, J.W. (1993). "Balancing trade-offs between risk and changing shoal size in northern red-belly dace (Phoxinus eos)". Copeia. 1993 (2): 540–542. doi:10.2307/1447157. JSTOR 1447157.

- Krause, J.; Godin, J.-G.J.; Rubenstein, D. (1998). "Group choice as a function of group size differences and assessment time in fish: the influence of species vulnerability to predation". Ethology. 104: 68–74. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1998.tb00030.x.

- van Havre, N.; FitzGerald, G J (1988). "Shoaling and kin recognition in the threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.)". Biology of Behaviour. 13: 190–201.

- Krause, J. (1993). "The influence of hunger on shoal size choice by three-spined sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus". Journal of Fish Biology. 43 (5): 775–780. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1993.tb01154.x.

- Allan, J.R.; Pitcher, T.J. (1986). "Species segregation during predator evasion in cyprinid fish shoals". Freshwater Biology. 16 (5): 653–659. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1986.tb01007.x.

- Ranta, E.; Lindstrom, K.; Peuhkuri, N. (1992). "Size matters when three-spined sticklebacks go to school". Animal Behaviour. 43: 160–162. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80082-x. S2CID 53177367.

- Ranta, E.; Juvonen, S.-K.; Peuhkuri, N. (1992). "Further evidence for size-assortative schooling in sticklebacks". Journal of Fish Biology. 41 (4): 627–630. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1992.tb02689.x.

- Krause, J. (1994). "The influence of food competition and predation risk on size-assortative shoaling in juvenile chub (Leuciscus cephalus)". Ethology. 96 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1994.tb00886.x.

- Krause, J.; Godin (2010). "J 1994, Shoal choice in the banded killifish (Fundulus diaphanus, Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae): effects of predation risk, fish size, species composition and size of shoals". Ethology. 98 (2): 128–136. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1994.tb01063.x.

- Reebs, S.G.; Saulnier, N. (1997). "The effect of hunger on shoal choice in golden shiners (Pisces: Cyprinidae, Notemigonus crysoleucas)". Ethology. 103 (8): 642–652. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1997.tb00175.x.

- Magurran, A.E.; Seghers, B.H.; Shaw, P.W.; Carvalho, G.R. (1994). "Schooling preferences for familiar fish in the guppy, Poecilia reticulata". Journal of Fish Biology. 45 (3): 401–406. doi:10.1006/jfbi.1994.1142.

- Griffiths, S.W.; Magurran, A.E. (1999). "Schooling decisions in guppies (Poecilia reticulata) are based on familiarity rather than kin recognition by phenotype matching". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 45 (6): 437–443. doi:10.1007/s002650050582. S2CID 23085058.

- Barber, I.; Ruxton, G.D. (2000). "The importance of stable schooling: do familiar sticklebacks stick together?". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 267 (1439): 151–155. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.0980. PMC 1690514. PMID 10687820.

- Lee-Jenkins, S.S.Y.; Godin, J.-G. J. (2010). "Social familiarity and shoal formation in juvenile fishes". Journal of Fish Biology. 76 (3): 580–590. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02512.x. PMID 20666898.

- Sikkel, P.C.; Fuller, C.A. (2010). "Shoaling preference and evidence for maintenance of sibling groups by juvenile black perch Embiotoca jacksoni". Journal of Fish Biology. 76 (7): 1671–1681. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02607.x. PMID 20557623.

- De Fraipont, M.; Thines, G. (1986). "Responses of the cavefish Astyanax mexicanus (Anoptichthys antrobius) to the odor of known and unknown conspecifics". Experientia. 42 (9): 1053–1054. doi:10.1007/bf01940729. S2CID 29725205.

- Brown, G.E.; Smith, R.J.F. (1994). "Fathead minnows use chemical cues to discriminate natural shoalmates from unfamiliar conspecifics". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 20 (12): 3051–3061. doi:10.1007/bf02033710. PMID 24241976. S2CID 31326304.

- Farmer, N.A.; Ribble, D.O.; Miller, III (2004). "Influence of familiarity on shoaling behaviour in Texas and blacktailed shiners". Journal of Fish Biology. 64 (3): 776–782. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2004.00332.x.

- Webster, M.M.; Adams, E.L.; Laland, K.N. (2008). "Diet-specific chemical cues influence association preferences and prey patch use in a shoaling fish". Animal Behaviour. 76: 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.12.010. S2CID 53175064.

- Dugatkin, L.A.; FitzGerald, G.J.; Lavoie, J. (1994). "Juvenile three-spined sticklebacks avoid parasitized conspecifics". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 39 (2): 215–218. doi:10.1007/bf00004940. S2CID 39806095.

- Krause, J.; Godin (2010). "J 1996, Influence of parasitism on shoal choice in the banded killifish (Fundulus diaphanus, Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae)". Ethology. 102: 40–49. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1996.tb01102.x.

- Barber, I.; Downey, L.C.; Braithwaite, V.A. (1998). "Parasitism, oddity and the mechanism of shoal choice". Journal of Fish Biology. 53 (6): 1365–1368. doi:10.1006/jfbi.1998.0788.

- Ward, A.J.W.; Duff, A.J.; Krause, J.; Barber, I. (2005). "Shoaling behaviour of sticklebacks infected with the microsporidian parasite, Glutea anomala". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 72 (2): 155–160. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.7259. doi:10.1007/s10641-004-9078-1. S2CID 21197916.

- Krause, J.; Hartmann, N.; Pritchard, V.L. (1999). "The influence of nutritional state on shoal choice in zebrafish, Danio rerio". Animal Behaviour. 57 (4): 771–775. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.1010. PMID 10202085. S2CID 25036232.

- Harcourt, J.L.; Sweetman, G.; Johnstone, R.A.; Manica, A. (2009). "Personality counts: the effect of boldness on shoal choice in three-spined sticklebacks". Animal Behaviour. 77 (6): 1501–1505. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.004. S2CID 53254313.

- Gomez-Laplaza, L.M. (2005). "The influence of social status on shoaling preferences in the freshwater angelfish (Pterophyllum scalare)". Behaviour. 142 (6): 827–844. doi:10.1163/1568539054729141. S2CID 145533152.

- Metcalfe, N.B.; Thomson, B.C. (1995). "Fish recognize and prefer to shoal with poor competitors". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 259 (1355): 207–210. Bibcode:1995RSPSB.259..207M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0030. S2CID 85131321.

- Pitcher, T.J.; House, A.C. (1987). "Foraging rules for group feeders: forage area copying depends upon food density in shoaling goldfish". Ethology. 76 (2): 161–167. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1987.tb00681.x.

- Krause, J (1992). "Ideal free distribution and the mechanism of patch profitability assessment in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus)". Behaviour. 123 (1–2): 27–37. doi:10.1163/156853992x00093.

- Reebs, S.G.; Gallant, B.Y. (1997). "Food-anticipatory activity as a cue for local enhancement in golden shiners (Pisces: Cyprinidae, Notemigonus crysoleucas)". Ethology. 103 (12): 1060–1069. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1997.tb00148.x. S2CID 84055118.

- Pritchard, V.L.; Lawrence, J.; Butlin, R.K.; Krause, J. (2001). "Shoal choice in zebrafish, Danio rerio: the influence of shoal size and activity". Animal Behaviour. 62 (6): 1085–1088. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1858. S2CID 53165127.

- Dominey, Wallace J. (1983). "Mobbing in Colonially Nesting Fishes, Especially the Bluegill, Lepomis macrochirus". Copeia. 1983 (4): 1086–1088. doi:10.2307/1445113. JSTOR 1445113.

- Fountain, Henry (24 May 2005). "Red-Bellied Piranha Is Really Yellow". New York Times. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Gilly, W.F.; Markaida, U.; Baxter, C.H.; Block, B.A.; Boustany, A.; Zeidberg, L.; Reisenbichler, K.; Robison, B.; Bazzino, G.; Salinas, C. (2006). "Vertical and horizontal migrations by the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas revealed by electronic tagging" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 324: 1–17. Bibcode:2006MEPS..324....1G. doi:10.3354/meps324001.

- Zimmermann, Tim (July 2006). "Behold the Humboldt squid". Outside Online. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- "The Curious Case of the Cannibal Squid – National Wildlife Federation". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Thomas, Pete (26 March 2007). "Warning lights of the sea". Los Angeles Times.

Further reading

- Bonabeau, E; Dagorn, L (1995). "Possible universality in the size distribution of fish schools" (PDF). Physical Review. 51 (6): R5220–R5223. Bibcode:1995PhRvE..51.5220B. doi:10.1103/physreve.51.r5220. PMID 9963400.

- Boinski S and Garber PA (2000) On the Move: How and why Animals Travel in Groups University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06339-3

- Breder, CM (1954). "Equations Descriptive of Fish Schools and Other Animal Aggregations". Ecology. 35 (3): 361–370. doi:10.2307/1930099. JSTOR 1930099.

- Childress S (1981) Mechanics of Swimming and Flying Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28071-6

- Camazine S, Deneubourg JL, Franks NR, Sneyd J, Theraulaz G and Bonabeau E (2003) Self-Organization in Biological Systems. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11624-2 – especially Chapter 11

- Evans, SR; Finniea, M; Manica, A (2007). "Shoaling preferences in decapod crustacea". Animal Behaviour. 74 (6): 1691–1696. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.03.017. S2CID 53150496.

- Delcourt, J; Poncin, P (2012). "Shoals and schools: back to the heuristic definitions and quantitative references". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 22 (3): 595–619. doi:10.1007/s11160-012-9260-z. S2CID 18306602.

- Gautrais, J., Jost, C. & Theraulaz, G. (2008) Key behavioural factors in a self-organised fish school model. Annales Zoologici Fennici 45: 415–428.

- Godin, JJ (1997) Behavioural Ecology of Teleost Fishes Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850503-7

- Ghosh S and Ramamoorthy CV (2004) Design for Networked Information Technology Systems Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95544-5

- Hager, MC; Helfman, GS (1991). "Safety in numbers: shoal size choice by minnows under predatory threat". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (4): 271–276. doi:10.1007/BF00163984. S2CID 30901973.

- Hemelrijk, CK; Hildenbrandt, H; Reinders, J; Stamhuis, EJ (2010). "Emergence of Oblong School Shape: Models and Empirical Data of Fish" (PDF). Ethology. 116 (11): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2010.01818.x.

- Hoare, DJ; Krause, J (2003). "Social organisation, shoal structure and information transfer". Fish and Fisheries. 4 (3): 269–279. doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2003.00130.x.

- Inada Y (2001) "Steering mechanism of fish schools" Complexity International, Vol 8, Paper ID Download

- Inagaki, T; Sakamoto, W; Aoki, I (1976). "Studies on the Schooling Behavior of Fish—III Mutual Relationship between Speed and Form in Schooling Behavior" (PDF). Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries. 42 (6): 629–635. doi:10.2331/suisan.42.629. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- Kato N and Ayers J (2004) Bio-mechanisms of Swimming and Flying Springer. ISBN 978-4-431-22211-8

- Kennedy J, Eberhart, RC and Shi Y (2001) Swarm Intelligence Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1-55860-595-4

- Krause, J (2005) Living in Groups Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850818-2

- Krause, J (2005). "Positioning behaviour in fish shoals: a cost–benefit analysis". Journal of Fish Biology. 43: 309–314. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1993.tb01194.x. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- Krause, J; Ruxton, GD; Rubenstein, D (2005). "Is there always an influence of shoal size on predator hunting success?". Journal of Fish Biology. 52 (3): 494–501. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb02012.x.

- Litvak, MK (1993). "Response of shoaling fish to the threat of aerial predation". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 36 (2): 183–192. doi:10.1007/BF00002798. S2CID 30214279.

- Lurton X (2003) Underwater Acoustics Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-42967-8

- Moyle PB and Van Dyck CM (1995) Fish: An Enthusiast's Guide University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20165-1

- Parrish JK and Hamner WM (1997) Animal Groups in Three Dimensions: How Species Aggregate Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46024-8

- Parrish, JK; Viscido, SV; Grunbaumb, D (2002). "Self-Organized Fish Schools: An Examination of Emergent Properties" (PDF). Biol. Bull. 202 (3): 296–305. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.116.1548. doi:10.2307/1543482. JSTOR 1543482. PMID 12087003. S2CID 377484.

- Partridge, BL (1982). "The structure and function of fish schools" (PDF). Scientific American. Vol. 246 no. 6. pp. 114–123. Bibcode:1982SciAm.246f.114P. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0682-114. PMID 7201674. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-03.

- Pitcher, TJ (1983). "Heuristic definitions of fish shoaling behavior". Animal Behaviour. 31 (2): 611–613. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(83)80087-6. S2CID 53195091.

- Pitcher TJ and Parish JK (1993) "Functions of shoaling behaviour in teleosts" In: Pitcher TJ (ed) Behaviour of teleost fishes. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 363–440

- Pitcher, TJ; Magurran, AE; Winfield, IJ (1982). "Fish in larger shoals find food faster". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 10 (2): 149–151. doi:10.1007/BF00300175. S2CID 6340986.

- Pitcher TJ (2010) "Fish schooling" In: Steele JH, Thorpe SA and Turekian KK (Eds.) Marine Biology, Academic Press, pages 337–349. ISBN 978-0-08-096480-5.

- Pryor K and Norris KS (1998) Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21656-3, ISBN 978-0-520-21656-3

- Ross DA (2000) The Fisherman's Ocean Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-2771-6

- Scalabrin, C; Massé, J (1993). "Acoustic detection of the spatial and temporal distribution of fish shoals in the Bay of Biscay". Aquatic Living Resources. 6 (3): 269–283. doi:10.1051/alr:1993027. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23.

- Seno, H; Nakai, K (1995). "Mathematical analysis on fish shoaling by a density-dependent diffusion model". Ecological Modelling. 79 (3): 149–157. doi:10.1016/0304-3800(93)E0143-Q.

- Simmonds EJ and MacLennan, DN (2005) Fisheries Acoustics Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-632-05994-2

- Suppi R, Fernandez D and Luque E (2003) Fish schools: PDES simulation and real-time 3D animation in Parallel Processing and Applied Mathematics: 5th International Conference, PPAM 2003, Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-21946-0

- Vicsek, A; Zafeiris, A (2012). "Collective motion". Physics Reports. 517 (3–4): 71–140. arXiv:1010.5017. Bibcode:2012PhR...517...71V. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2012.03.004. S2CID 119109873.

- White TI (2007) In Defense of Dolphins Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-5779-7

- Wolf, NG (1985). "Odd fish abandon mixed-species groups when threatened". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 17 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1007/bf00299428. S2CID 11935938.

- Wootton, RJ (1998) Ecology of Teleost Fishes Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-64200-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schools of fish. |

- Collective Animal Behavior website organized around David Sumpter's book (2008) by the same name

- STARFLAG project: Description of starling flocking project

- Center for Biologically Inspired Design at Georgia Tech

- David Sumpter's research website

- Iain Couzin's research website

- Website of Julia Parrish, an animal aggregation researcher

- Pelagic Fisheries Research Program (2002) Current status and new directions for studying schooling and aggregation behavior of pelagic fish

- Clover, Charles (2008) Fish can count to four – but no higher Telegraph Media Group.

- Herring Migratory Behaviour

- Example of schooling simulation

- Bhaduri, Aparna (2010) Schooling in Fish OpenStax College. Updated 16 July 2010.