Gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding.

History

Early history

The Greek geographer Strabo reports in his Geography a water-powered grain-mill to have existed near the palace of king Mithradates VI Eupator at Cabira, Asia Minor, before 71 BC.[1]

The early mills had horizontal paddle wheels, an arrangement which later became known as the "Norse wheel", as many were found in Scandinavia.[2] The paddle wheel was attached to a shaft which was, in turn, attached to the centre of the millstone called the "runner stone". The turning force produced by the water on the paddles was transferred directly to the runner stone, causing it to grind against a stationary "bed", a stone of a similar size and shape.[2] This simple arrangement required no gears, but had the disadvantage that the speed of rotation of the stone was dependent on the volume and flow of water available and was, therefore, only suitable for use in mountainous regions with fast-flowing streams.[2] This dependence on the volume and speed of flow of the water also meant that the speed of rotation of the stone was highly variable and the optimum grinding speed could not always be maintained.[2]

Vertical wheels were in use in the Roman Empire by the end of the first century BC, and these were described by Vitruvius.[3] The peak of Roman technology is probably the Barbegal aqueduct and mill where water with a 19-metre fall drove sixteen water wheels, giving a grinding capacity estimated at 28 tons per day.[4] Water mills seem to have remained in use during the post-Roman period.

Manually operated mills utilizing a crank-and-connecting rod were used in the Western Han Dynasty.[5]

There was an expansion of grist-milling in the Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Persia from the 3rd century AD onwards, and then the widespread expansion of large-scale factory milling installations across the Islamic world from the 8th century onwards.[6] Geared gristmills were built in the medieval Near East and North Africa, which were used for grinding grain and other seeds to produce meals.[7] Gristmills in the Islamic world were powered by both water and wind. The first wind-powered gristmills were built in the 9th and 10th centuries in what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.[8] The Egyptian town of Bilbays had a grain-processing factory that produced an estimated 300 tons of flour and grain per day.[9]

From the late 10th century onwards, there was an expansion of grist-milling in Northern Europe.[6] In England, the Domesday survey of 1086 gives a precise count of England's water-powered flour mills: there were 5,624, or about one for every 300 inhabitants, and this was probably typical throughout western and southern Europe. From this time onward, water wheels began to be used for purposes other than grist milling. In England, the number of mills in operation followed population growth, and peaked at around 17,000 by 1300.[10]

Limited extant examples of gristmills can be found in Europe from the High Middle Ages. An extant well-preserved waterwheel and gristmill on the Ebro River in Spain is associated with the Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda, built by the Cistercian monks in 1202. The Cistercians were known for their use of this technology in Western Europe in the period 1100 to 1350.

Classical British and American mills

Although the terms "gristmill" or "corn mill" can refer to any mill that grinds grain, the terms were used historically for a local mill where farmers brought their own grain and received back ground meal or flour, minus a percentage called the "miller's toll."[11] Early mills were almost always built and supported by farming communities and the miller received the "miller's toll" in lieu of wages. Most towns and villages had their own mill so that local farmers could easily transport their grain there to be milled. These communities were dependent on their local mill as bread was a staple part of the diet.

Classical mill designs are usually water-powered, though some are powered by the wind or by livestock. In a watermill a sluice gate is opened to allow water to flow onto, or under, a water wheel to make it turn. In most watermills the water wheel was mounted vertically, i.e., edge-on, in the water, but in some cases horizontally (the tub wheel and so-called Norse wheel). Later designs incorporated horizontal steel or cast iron turbines and these were sometimes refitted into the old wheel mills.

In most wheel-driven mills, a large gear-wheel called the pit wheel is mounted on the same axle as the water wheel and this drives a smaller gear-wheel, the wallower, on a main driveshaft running vertically from the bottom to the top of the building. This system of gearing ensures that the main shaft turns faster than the water wheel, which typically rotates at around 10 rpm.

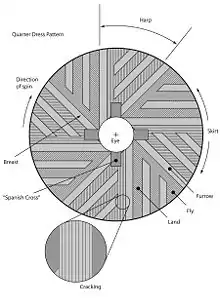

The millstones themselves turn at around 120 rpm. They are laid one on top of the other. The bottom stone, called the bed, is fixed to the floor, while the top stone, the runner, is mounted on a separate spindle, driven by the main shaft. A wheel called the stone nut connects the runner's spindle to the main shaft, and this can be moved out of the way to disconnect the stone and stop it turning, leaving the main shaft turning to drive other machinery. This might include driving a mechanical sieve to refine the flour, or turning a wooden drum to wind up a chain used to hoist sacks of grain to the top of the mill house. The distance between the stones can be varied to produce the grade of flour required; moving the stones closer together produces finer flour.

The grain is lifted in sacks onto the sack floor at the top of the mill on the hoist. The sacks are then emptied into bins, where the grain falls down through a hopper to the millstones on the stone floor below. The flow of grain is regulated by shaking it in a gently sloping trough (the slipper) from which it falls into a hole in the center of the runner stone. The milled grain (flour) is collected as it emerges through the grooves in the runner stone from the outer rim of the stones and is fed down a chute to be collected in sacks on the ground or meal floor. A similar process is used for grains such as wheat to make flour, and for maize to make corn meal.

In order to prevent vibrations from the millstones shaking the building apart, they were usually placed on a separate timber foundation, not attached to the mill walls, known as a husk. This foundation isolated the building from vibrations coming from the stones and main gearing and also allowed for the easy re-leveling of the foundation to keep the millstones perfectly horizontal. The lower bedstone was placed in an inset in the husk with the upper runner stone above the level of the husk.

The automatic mill

American inventor Oliver Evans revolutionized the labor-intensive process of early mills at the end of the eighteenth century when he automated the process of making flour. His inventions included the Elevator, wood or tin buckets on a vertical endless leather belt, used to move grain and flour vertically upward; the Conveyor, a wooden auger to move material horizontally; the Hopper Boy, a device for stirring and cooling the newly ground flour; the Drill, a horizontal elevator with flaps instead of buckets (similar to the use of a conveyor but easier to build); and the Descender, an endless strap (leather or flannel) in a trough that is angled downward, the strap helps to move the ground flour in the trough. Most importantly, he integrated these into a single continuous process, the overall design later becoming known as the Automatic (or Automated) mill. In 1790 he received the third Federal patent for his process. In 1795 he published "The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide" which fully described the process. [12]

Evans himself did not use the term gristmill to describe his automatic flour mill, which was purpose designed as a merchant mill (he used the more general term "water-mill"). In his book his only reference to "grist" (or "grists") is to the small batches of grain a farmer would bring in to have ground for himself (what would be generally called barter or custom milling). In his book, Evans describes a system that allows the sequential milling of these grists, noting that "a mill, thus constructed, might grind grists in the day time, and do merchant-work at night." [13] Over time, any small, older style flour mill became generally known as a gristmill (as a distinction from large factory flour mills).

Modern mills

.jpg.webp)

Modern mills typically use electricity or fossil fuels to spin heavy steel, or cast iron, serrated and flat rollers to separate the bran and germ from the endosperm. The endosperm is ground to create white flour, which may be recombined with the bran and germ to create whole grain or graham flour. The different milling techniques produce visibly different results, but can be made to produce nutritionally and functionally equivalent output. Stone-ground flour is, however, preferred by many bakers and natural food advocates because of its texture, nutty flavour, and the belief that it is nutritionally superior and has a better baking quality than steel-roller-milled flour.[14] It is claimed that, as the stones grind relatively slowly, the wheat germ is not exposed to the sort of excessive temperatures that could cause the fat from the germ portion to oxidize and become rancid, which would destroy some of the vitamin content.[14] Stone-milled flour has been found to be relatively high in thiamin, compared to roller-milled flour, especially when milled from hard wheat.[14]

Gristmills only grind "clean" grains from which stalks and chaff have previously been removed, but historically some mills also housed equipment for threshing, sorting, and cleaning prior to grinding.

Modern mills are usually "merchant mills" that are either privately owned and accept money or trade for milling grains or are owned by corporations that buy unmilled grain and then own the flour produced.

Pests

One common pest found in flour mills is the Mediterranean flour moth. Moth larvae produce a web-like material that clogs machinery, sometimes causing grain mills to shut down.[15]

Gallery

Gristmill with water wheel, Skyline Drive, Virginia, 1938

Gristmill with water wheel, Skyline Drive, Virginia, 1938 Gristmill hopper, Skyline Drive, VA, 1938. Grain was funneled through the hopper to a grinding stone below

Gristmill hopper, Skyline Drive, VA, 1938. Grain was funneled through the hopper to a grinding stone below Gristmill drive machinery, Thomas Mill, Chester County, PA

Gristmill drive machinery, Thomas Mill, Chester County, PA Pedal powered wheat mill, Shediac Cape, New Brunswick

Pedal powered wheat mill, Shediac Cape, New Brunswick Remnants of some of the scores of flour mills built in Minneapolis between 1850 and 1900. Note the underground Mill race that powered mills on the west side of the Mississippi River at St. Anthony Falls

Remnants of some of the scores of flour mills built in Minneapolis between 1850 and 1900. Note the underground Mill race that powered mills on the west side of the Mississippi River at St. Anthony Falls Wheel of the 1840s-era Grist Mill at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA

Wheel of the 1840s-era Grist Mill at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA "Slipper" feeding corn into the grindstones of George Washington's Grist Mill

"Slipper" feeding corn into the grindstones of George Washington's Grist Mill Old turbine wheel at the old grist mill in Thorp, Washington

Old turbine wheel at the old grist mill in Thorp, Washington The grist mill at the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts

The grist mill at the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts

References

- Wikander 1985, p. 160; Wikander 2000, p. 396

- Denny, Mark (4 May 2007). "Waterwheels and Windmills". Ingenium: five machines that changed the world. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-8018-8586-0. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

norse wheel.

- Oleson, John Peter (30 Jun 1984). Greek and Roman mechanical water-lifting devices: the history of a technology. Springer. p. 373. ISBN 90-277-1693-5. ASIN 9027716935.

- Hill, Donald (2013). A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times. Routledge. pp. 163–164. ISBN 9781317761570.

- Hong-Sen Yan, Marco Ceccarelli (2009). International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. Springer Science and Business Media. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4020-9484-2.

- Hill, Donald (2013). A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 9781317761570.

- Donald Routledge Hill (1996), "Engineering", p. 781, in (Rashed & Morelon 1996, pp. 751–95)

- Adam Lucas (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, p. 65, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-14649-0

- Hill, Donald (2013). A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 9781317761570.

- Gimpel, J., The Medieval Machine, Gollanz, 1976, Chapter 1.

- "ARTFL Project: Webster Dictionary, 1913". The University of Chicago - Department of Romance Languages and Literature. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- http://www.deltamill.org/history.html

- Evans, Oliver, The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide, Oliver Evans, Philadelphia, 1795, Chapter II, pp.88-90

- Campbell, Judy; Mechtild Hauser; Stuart Hill (1991). "NUTRITIONAL CHARACTERISTICS of ORGANIC, FRESHLY STONE-GROUND, SOURDOUGH & - CONVENTIONAL BREADS". Ecological Agriculture Projects Publications. Ecological Agriculture Projects. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- "Mediterranean Flour Moth (Department of Entomology)". Department of Entomology (Penn State University). Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- Wikander, Örjan (1985). "Archaeological Evidence for Early Water-Mills. An Interim Report". History of Technology. 10. pp. 151–79.

- Wikander, Örjan (2000). "The Water-Mill". In Wikander, Örjan (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Water Technology. Technology and Change in History. 2. Leiden: Brill. pp. 371–400. ISBN 90-04-11123-9.

Further reading

- Richard Bennett & John Elton. History of corn milling (London, Simpkin, Marshall and company, 1898).

- Volume 1 - Handstone, Slave and Cattle Mills

- Volume 2 - Water and Wind Mills

- Volume 3 - Feudal Laws and customs of Mills

- Volume 4 - Some famous feudal mills

- History of Cannon River Mills in Southern MN, USA