Guge

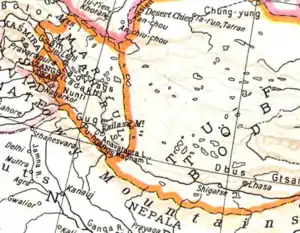

Guge (Tibetan: གུ་གེ་, Wylie: gu ge ) was an ancient kingdom in Western Tibet. The kingdom was centered in present-day Zanda County, Ngari Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region. At various points in history after the 10th century AD, the kingdom held sway over a vast area including south-eastern Zanskar, Upper Kinnaur district, and Spiti Valley, either by conquest or as tributaries. The ruins of the former capital of the Guge kingdom are located at Tsaparang in the Sutlej valley, not far from Mount Kailash and 1,200 miles (1,900 km) westwards from Lhasa.

History

Guge was founded in the 10th century. Its capitals were located at Tholing and Tsaparang.[1] Nyi ma mgon, a great-grandson of Langdarma, the last monarch of the Tibetan Empire, left insecure conditions in Ü-Tsang in 910. He established a kingdom in Ngari (West Tibet) in or after 912 and annexed Puhrang and Guge. He established his capital in Guge.

Nyi ma mgon later divided his lands into three parts. The king's eldest son dPal gyi mgon became ruler of Mar-yul (Ladakh), his second son bKra shis mgon received Guge-Puhrang, and the third son lDe gtsug mgon received Zanskar. bKra shis mgon was succeeded by his son Srong nge or Ye shes 'Od (947–1024 or (959–1036), who was a renowned Buddhist figure. In his time a Tibetan lotsawa from Guge called Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055), after having studied in India, returned to his homeland as a monk to promote Buddhism. Together with the zeal of Ye shes 'Od, this marked the beginning of a new diffusion of Buddhist teachings in western Tibet. In 988 Ye shes 'Od took religious vows and left kingship to his younger brother Khor re.

According to later historiography the Turkic Karluks took the Guge king Ye shes 'Od prisoner during a war.[2] The episode has a prominent place in Tibetan history writing. The Karluks offered to set him free if he renounced Buddhism which he refused to do. They then demanded his weight in gold to release him. His junior kinsman Byang chub 'Od visited him in his prison with a small retinue, but Ye shes 'Od admonished him not to use the gold at hand for ransom, but rather to invite the renowned Mahayana sage Atiśa (982–1054). Ye shes 'Od eventually died in prison from age and poor treatment.[3] The story is historically debated since it contains chronological inconsistencies.

In 1037, Khor re's eldest grandson 'Od lde was killed in a conflict with the Kara-Khanid Khanate from Central Asia, who subsequently ravaged Ngari. His brother Byang chub 'Od (984–1078), a Buddhist monk, took power as secular ruler. He was responsible for inviting Atiśa to Tibet in 1040 and thus ushering in the so-called Chidar (Phyi-dar) phase of Buddhism in Tibet. Byang chub 'Od's son rTse lde was murdered by his nephew in 1088. This event marked the break-up of the Guge-Purang kingdom, since one of his brothers was established as separate king of Purang. The usurping nephew dBang lde continued the royal dynasty in Guge.[4]

A new Kara-Khanid invasion of Guge took place before 1137 and cost the life of the ruler, bKra shis rtse. Later in the same century the kingdom was temporarily divided. In 1240 the Mongol khagan, at least nominally, gave authority over the Ngari area to the Drigung Monastery in Ü-Tsang.

Grags pa lde was an important ruler who united the Guge area around 1265 and subjugated the related Ya rtse (Khasa) kingdom. After his death in 1277 Guge was dominated by the Sakya monastic regime. After 1363, with the decline of the Mongol Yuan dynasty and their Sakya protégés, Guge was again strengthened and took over Purang in 1378. Purang was henceforth contested between Guge and Mustang, but was finally integrated in the former. Guge also briefly ruled over Ladakh in the late 14th century. From 1499 the Guge king had to acknowledge the Rinpungpa rulers of Tsang. The 15th and 16th centuries were marked by a considerable Buddhist building activity by the kings, who frequently showed their devotion to the Gelug leaders later known as the Dalai Lamas.[5]

The first Westerners to reach Guge were a Jesuit missionary, António de Andrade, and his companion, brother Manuel Marques, in 1624. De Andrade reported seeing irrigation canals and rich crops in what is now a dry and desolate land. Perhaps as evidence of the kingdom's openness, de Andrade's party was allowed to construct a chapel in Tsaparang and instruct the people about Christianity.[6] A letter by De Andrade relates that some military commanders revolted and called the Ladakhis to overthrow the ruler. There had been friction between Guge and Ladakh for many years, and the invitation was heeded in 1630. The Ladakhi forces laid siege to the almost impenetrable Tsaparang. The King's brother, who was chief lama and thus a staunch Buddhist, advised the pro-Christian ruler to surrender against keeping the state as tributary ruler. This treacherous advice was eventually accepted. Tibetan sources suggest that the Guge population was maintained in their old status.[7] A legend has it that the Ladakhi army slaughtered most of the people of Guge, about 200 of whom managed to survive and fled to Qulong.[8] The last king Khri bKra shis Grags pa lde was brought to Ladakh as prisoner with his kin, and died there. The King's brother-lama was killed by the Ladakhis. Later on the last male descendant of the dynasty moved to Lhasa where he died in 1743.[9]

Tsaparang and the Guge kingdom were later conquered in 1679–80 by the Lhasa-based Central Tibetan government under the leadership of the 5th Dalai Lama, driving out the Ladakhis.

Western archeologists heard about Guge again in the 1930s through the work of Italian Giuseppe Tucci. Tucci's work was mainly about the frescoes of Guge. Lama Anagarika Govinda and Li Gotami Govinda visited the kingdom of Guge, including Tholing, and Tsaparang, in 1947–1949. Their tours of Central and Western Tibet are recorded in black-and-white photos.[10]

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Rulers

A list of rulers of Guge and the related Ya rtse kingdom has been established by the Tibetologists Luciano Petech and Roberto Vitali[11]

A. Royal ancestors of the Tubo dynasty.

- 'Od srungs (in Central Tibet 842–905) son of Glang Darma

- dPal 'Khor btsan (in Central Tibet 905–910) son

- sKyid lde Nyi ma mgon (in Ngari Korsum, c. 912–?) son

- dPal gyi mgon (received Ladakh, 10th century) son

- lDe gtsug mgon (received Zanskar, 10th century) brother

B. Kings of Guge and Purang.

- bKra shis mgon (received Guge and Purang, fl. 947) brother

- Srong nge Ye shes 'Od (?–988 or 959–1036) son

- Nagaraja (religious leader, d. 1023) son

- Devaraja (religious leader, d. 1026) brother

- Khor re (988–996) uncle

- Lha lde (996–1024) son

- 'Od lde btsan (1024–1037) son

- Byang chub 'Od (1037–1057) brother

- Zhi ba 'Od (religious leader, d. 1111) brother

- Che chen tsha rTse lde (1057–1088) son of Byang chub 'od

C. Kings of Ya rtse.

- Naga lde (early 12th century)

- bTsan phyug lde (mid-12th century)

- bKra shis lde (12th century)

- Grags btsan lde (12th century) brother of bTsan phyug lde)

- Grags pa lde (Kradhicalla) (fl. 1225)

- A sog lde (Ashokacalla) (fl. 1255–1278) son

- 'Ji dar sMal (Jitarimalla) (fl. 1287–1293) son

- A nan sMal (Anandamalla) (late 13th century) brother

- Ri'u sMal (Ripumalla) (fl. 1312–1214) son

- San gha sMal (Sangramamalla) (early 14th century) son

- Ajitamalla (1321–1328) son of Jitarimalla

- Kalyanamalla (14th century)

- Pratapamalla (14th century)

- Pu ni sMal (Punyamalla) (fl. 1336–1339) of Purang royalty

- sPri ti sMal (Prthivimalla) (fl. 1354–1358) son

D. Kings of Guge.

- Bar lde (dBang lde) (1088 – c. 1095) nephew of Che chen tsha rTse lde

- bSod nams rtse (c. 1095 – early 12th century) son

- bKra shis rtse (before 1137) son

- Jo bo rGyal po (regent, mid-12th century) brother

- rTse 'bar btsan (12th century) son of bKra shis rtse

- sPyi lde btsan (12th century) son

- rNam lde btsan (12th/13th century) son

- Nyi ma lde (12th/13th century) son

- dGe 'bum (13th century) probably an outsider

- La ga (died c. 1260) of foreign origin

- Chos rgyal Grags pa (c. 1260–1265)

- Grags pa lde (c. 1265–1277) prince from Lho stod

- unknown rulers

- rNam rgyal lde (c. 1396 – 1424) son of a Guge ruler

- Nam mkha'i dBang po Phun tshogs lde (1424–1449) son

- rNam ri Sang rgyas lde (1449–?) son

- bLo bzang Rab brtan (died c. 1485) son

- sTod tsha 'Phags pa lha (c. 1485 – after 1499) son

- Shakya 'od (early 16th century) son

- Jig rten dBang phyug Pad kar lde (fl. 1537–1555) son?

- Ngag gi dBang phyug (16th century) son

- Nam mkha dBang phyug (16th century) son

- Khri Nyi ma dBang phyug (late 16th century) son

- Khri Grags pa'i dBang phyug (c. 1600) son

- Khri Nam rgyal Grags pa lde (fl. 1618) son

- Khri bKra shis Grags pa lde (before 1622–1630) son

- Kingdom conquered by Ladakh (1630)

- Kingdom later conquered by Tibet under the Fifth Dalai Lama (1679–1680)

See also

References

Specific references:

- .Snelling, John. (1990). The Sacred Mountain: The Complete Guide to Tibet's Mount Kailas. 1st edition 1983. Revised and enlarged edition, including: Kailas-Manasarovar Travellers' Guide. Forwards by H.H. the Dalai Lama of Tibet and Christmas Humphreys, p. 181. East-West Publications, London and The Hague. ISBN 0-85692-173-4.

- Christopher I. Beckwith (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. pp. 169ff. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa (1967), Tibet: A political history. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 56–57.

- Hoffman, Helmut, "Early and Medieval Tibet", in Sinor, David, ed., Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 388, 394; A. McKay, ed. (2003), The History of Tibet, Volume II. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 53–66.

- A. McKay, ed. (2003), pp. 42–45, 68–89.

- McKinnon, John. "The Kingdom of Guge, Western Tibet: an account of its history, Western visitors and significance". www.greenkiwi.co.nz. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- L. Petech (1977), The Kingdom of Ladakh, c. 950–1842 A.D. Rome: IsMEO, pp. 44-45.

- "Guge, a lost kingdom in Tibet". Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- A. McKay, ed. (2003), p. 44.

- Li Gotami Govinda, Tibet in Pictures (Berkeley, Dharma Publishing, 1979), 2 volumes.

- L. Petech (1980), 'Ya-ts'e, Gu-ge, Pu-rang: A new study', The Central Asiatic Journal 24, pp. 85–111; R. Vitali (1996), The kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang. Dharamsala: Tho.ling gtsug.lag.khang.

General references:

- Allen, Charles. (1999) The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown and Company. Reprint: 2000 Abacus Books, London. ISBN 0-349-11142-1.

Further reading

- Bellezza, John Vincent: Zhang Zhung. Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts, and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Denkschriften der phil.-hist. Klasse 368. Beitraege zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens 61, Verlag der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 2008.

- van Ham, Peter. (2017). Guge--Ages of Gold: The West Tibetan Masterpieces. Hirmer Verlag, 390 pages, ISBN 978-3777426686

- Zeisler, Bettina. (2010). "East of the Moon and West of the Sun? Approaches to a Land with Many Names, North of Ancient India and South of Khotan." In: The Tibet Journal, Special issue. Autumn 2009 vol XXXIV n. 3-Summer 2010 vol XXXV n. 2. "The Earth Ox Papers", edited by Roberto Vitali, pp. 371–463.

External links

- "Submerged in the Cosmos" by David Shulman, The New York Review of Books, February 24, 2017, retrieved March 2, 2017.

- "Unravelling the mysteries of Guge" by Xiong Lei, China Daily, May 8, 2003, retrieved November 24, 2005