Guido of Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo[lower-alpha 1] (c. 991 – after 1033)[1] was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of the medieval era. He is regarded as the inventor of modern staff notation that replaced neumatic notation. His text, the Micrologus, was the second most widely distributed treatise on music in the Middle Ages (after the writings of Boethius).

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

Life

Guido was a Benedictine monk from the Italian city-state of Arezzo. Recent research has dated his Micrologus to 1025 or 1026; since Guido stated in a letter that he was thirty-four when he wrote it,[2] his birthdate is presumed to be around 991 or 992. His early career was spent at the monastery of Pomposa, on the Adriatic coast near Ferrara. While there, he noted the difficulty that singers had in remembering Gregorian chants.

He came up with a method for teaching the singers to learn chants in a short time, and quickly became famous throughout north Italy. However, around 1025 he attracted the hostility of the other monks at the abbey who resisted his musical innovations, prompting him to move to Arezzo, a town which had no abbey, but which did have a large group of cathedral singers, whose training Bishop Tedald invited him to conduct.[3]

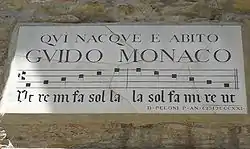

While at Arezzo, he developed new techniques for teaching, such as staff notation and the use of the "ut–re–mi–fa–sol–la" (do–re–mi–fa–so–la) mnemonic (solmization). The ut–re–mi-fa-sol-la syllables are taken from the initial syllables of each of the first six half-lines of the first stanza of the hymn Ut queant laxis, whose text is attributed to the Italian monk and scholar Paulus Diaconus (though the musical line either shares a common ancestor with the earlier setting of Horace's "Ode to Phyllis" (Odes 4.11), recorded in the Montpellier manuscript H425, or may have been taken from it).[2] Giovanni Battista Doni is known for having changed the name of note "Ut" (C), renaming it "Do" (in the "Do Re Mi ..." sequence known as solfège).[4] A seventh note, "Si" (from the initials for "Sancte Iohannes," Latin for St. John the Baptist) was added shortly after to complete the diatonic scale.[5] In anglophone countries, "Si" was changed to "Ti" by Sarah Glover in the nineteenth century so that every syllable might begin with a different letter (this also freed up Si for later use as Sol-sharp). "Ti" is used in tonic sol-fa and in the song "Do-Re-Mi".

The Micrologus, written at the cathedral at Arezzo and dedicated to Tedald, contains Guido's teaching method as it had developed by that time. Soon it had attracted the attention of Pope John XIX, who invited Guido to Rome. Most likely he went there in 1028, but he soon returned to Arezzo, due to his poor health. It was then that he announced in a letter to Michael of Pomposa ("Epistola de ignoto cantu") his discovery of the "ut–re–mi" musical mnemonic. Little is known of him after this time.

The Guidonian hand

Guido is credited with the invention of the Guidonian hand[1][6] a widely used mnemonic system where note names are mapped to parts of the human hand. However, only a rudimentary form of the Guidonian hand is actually described by Guido, and the fully elaborated system of natural, hard, and soft hexachords cannot be securely attributed to him.[7]

In the 12th century, a development in teaching and learning music in a more efficient manner had arisen. Guido of Arezzo's alleged development of the Guidonian hand, more than a hundred years after his death, allowed for musicians to label a specific joint or fingertip with the gamut (also referred to as the hexachord in the modern era). Using specific joints of the hand and fingertips transformed the way one would learn and memorize solmization syllables. Not only did the Guidonian hand become a standard use in preparing music in the 12th century, its popularity grew more widespread well into the 17th and 18th century.[8] The knowledge and use of the Guidonian hand would allow a musician to simply transpose, identify intervals, and aid in use of notation and the creation of new music. Musicians were able to sing and memorize longer sections of music and counterpoint during performances and the amount of time spent diminished dramatically.[9]

Legacy

A monument to him was erected in his native Arezzo. He is one of the famous Tuscans honored by a statue in the Loggiato of the Uffizi in Florence.

The computer music notation system GUIDO music notation is named after him and his invention.

The "International Guido d'Arezzo Polyphonic Contest" (Concorso Polifónico Guido d'Arezzo) is named after him.

Francisco Valls' controversial Missa Scala Aretina took its name from Guido Aretinus' scale.

See also

Notes

- Guido's name is recorded in many variants, including Guido Aretinus, Guido Aretino, Guido da Arezzo, Guido Monaco, Guido d'Arezzo, Guido Monaco Pomposiano, or Guy of Arezzo also Guy d'Arezzo

References

- Palisca 2001.

- Stuart Lyons, Horace's Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi with Full Verse Translation of the Odes. Oxford: Aris & Phillips, 2007. ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7.

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Guido-dArezzo-Italian-musician

- McNaught, W. G. (1893). "The History and Uses of the Sol-fa Syllables". Proceedings of the Musical Association. London: Novello, Ewer and Co. 19: 35–51. ISSN 0958-8442. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 271–7). ISBN 978-0-19-520912-9; ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7.

- "Solmization" by Andrew Hughes and Edith Gerson-Kiwi, Grove Music Online (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Claude V. Palisca, "Theory, Theorists, §5: Early Middle Ages", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers).

- Bonnie J. Blackburn, "Lusitano, Vicente", Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. accessed 13 July 2016.

- Don Michael Randel, "Guido of Arezzo", The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996): 339–40.

Sources

- Palisca, Claude V. (2001). "Guido of Arezzo". Grove Music Online. Revised by Dolores Pesce. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11968. Retrieved 19 September 2020. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

Further reading

- Hoppin, Richard (1978). Medieval Music. The Norton Introduction to Music History (1st ed.). New York, New York, US: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-09090-1.

- Stuart Lyons, Music in the Odes of Horace. Oxford: Aris & Phillips, 2010. ISBN 978-0-85668-844-7.

- Randel, Don Michael. "Guidonian Hand" in The New Harvard Dictionary of Music. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1986. Print.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Guido of Arezzo. |

Media related to Guido of Arezzo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guido of Arezzo at Wikimedia Commons- Reisenweaver, Anna (2012). "Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning", Musical Offerings: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 4.

Otten, Joseph (1913). "Guido of Arezzo". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Otten, Joseph (1913). "Guido of Arezzo". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Free scores by Guido of Arezzo at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)