Gusen concentration camp

Gusen was a subcamp of Mauthausen concentration camp operated by the SS (Schutzstaffel) between the villages of Sankt Georgen an der Gusen and Langestein in the Reichsgau Ostmark (currently Perg District, Upper Austria). Primarily populated by Polish prisoners, there were also large numbers of Spanish Republicans, Soviet citizens, and Italians. Initially, prisoners worked in nearby quarries, producing granite which was sold by the SS company DEST.

| Gusen | |

|---|---|

| Subcamp | |

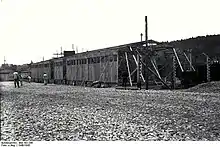

Gusen I after liberation | |

| Location | near Sankt Georgen an der Gusen, Reichsgau Ostmark |

| Operated by | Nazi Germany |

| Companies involved | DEST, Messerschmitt, Steyr-Daimler-Puch, Poschacher |

| Operational | 25 May 1940–5 May 1945 |

| Number of inmates | 20,487 (May 1945) |

| Killed | At least 35,000 |

| Liberated by | 11th Armored Division (United States) |

| Website | www |

Conditions were worse than at the Mauthausen main camp due to the camp's purpose of extermination through labor of real and perceived enemies of Nazi Germany. The life expectancy of prisoners was as short as six months, and at least 35,000 people died there from forced labor, starvation, and mass executions. From 1943, the camp was an important center of armaments production for Messerschmitt and Steyr-Daimler-Puch. In order to expand armaments production, the camp was redesignated Gusen I, and additional camps, Gusen II and Gusen III, were built. Prisoners were forced to construct vast underground factories, the main one being the Bergkristall, intended for the production of Messerschmitt 262 jet fighter aircraft. Nearly a thousand fuselages were produced there by the war's end.

The camp was liberated by the United States 11th Armored Division early in the morning of 5 May, 1945. During the chaos of liberation, a number of former kapos were killed. After the war, some SS personnel and kapos were tried for their crimes, although most went unpunished. The site was redeveloped into a privately owned village, although there is a small museum run by the Austrian government.

Background

Following World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up. Most Austrians wanted a union with Germany, but the Allied victors forbade a plebiscite from being held and forced the new country to change its name from "Republic of German-Austria" to "Republic of Austria".[1] On 13 March 1938, Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in the Anschluss; German forces were greeted by enthusiastic crowds. Immediately afterwards, a reign of terror began against anti-Nazis, Jews, and Austrians mistaken for Jews. The Gestapo established an office in Vienna two days later.[2] Hundreds were arrested and deported to Dachau concentration camp.[3]

The site of Mauthausen concentration camp was chosen in May 1938 by an SS delegation including Theodor Eicke and Oswald Pohl. Along with Flossenbürg concentration camp, its purpose was to quarry granite for Nazi architectural projects. The location was chosen for the quarries around the villages of Mauthausen and Sankt Georgen an der Gusen, leased by the SS enterprise DEST. The concentration camp, located 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Linz, was officially established in August. By the end of next month, prisoners from Dachau had finished the barracks for prisoners and the SS.[4][5][6] The quarry near Gusen was on land leased and later purchased from the Poschacher firm.[7][6] It is likely that the SS had already been planning to build a concentration camp because the deal for the Gusen quarry was made in May 1938, before that of the Mauthausen quarry.[6][8]

Establishment

The first and largest subcamp of Mauthausen,[9] Gusen began in December 1939 with a work detail of 10 or 12 German and Austrian prisoners who were assigned to build barracks adjacent to the Gusen quarry, just 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from Mauthausen.[10][11][8] The camp was built to increase the productivity of workers at the quarry just north of the site, who otherwise had to walk from the Mauthausen main camp and back again, reducing their productive hours. Of all the quarries near Mauthausen, Gusen produced most of the architectural quality granite;[12] it also produced freestone, paving stone, and gravel which was sold by DEST.[13] By January, the number of prisoners on the detail had increased to 400 and it included Polish prisoners from March.[10][8] The prisoners were not given coats or gloves, and were not allowed to access the fires lit by kapos and SS guards.[14] About 1,800 Mauthausen prisoners died between December and April, many of them while working on the construction details at Gusen.[15] The camp was officially opened on 25 May 1940, when the first prisoners and guards moved in.[16][13][8] The camp was directly adjacent to the road between Sankt Georgen an der Gusen and nearby Langenstein;[17][10] former prisoners recalled Austrian children passing by on the way to school. Until the camp wall was completed, passerby had a full view of what was happening in the camp.[17]

Conditions

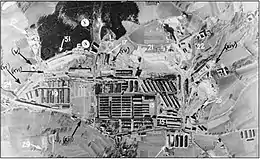

Mauthausen and Gusen were the only concentration camps rated by the SS as Category III, the highest rating,[6] and conditions in Gusen were even worse than at the main camp.[11] In 1940 and 1941, the average life expectancy was six months, and the average weight of prisoners in 1940–1942 was 40 kilograms (88 lb).[18] In late 1941, a typhus epidemic broke out, which resulted in the mass killing of ill prisoners.[19] The main purpose of the camp was extermination through labor of real and perceived political enemies of the Reich, rather than exploitation of their economic potential through slave labor, so mortality rates were higher than at most concentration camps. One group of prisoners would die, but the number was maintained due to transports of incoming prisoners.[20] Thus, the number of prisoners was maintained at around 6,000 to 7,000 until 1943 despite the high death rate.[21] Work in the quarries, which was specifically intended to cause the death of prisoners, continued until the end of the war despite the opening of war production.[22] Prisoners faced starvation rations, forced labor, and beatings by guards and kapos, while being denied basic sanitary facilities.[13] The camp for prisoner accommodations was a rectangle, which covered 180 by 400 metres (590 ft × 1,310 ft) and had 32 prisoner barracks, was surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. Its intended capacity of 4,000 to 5,000 prisoners was soon exceeded. Twice a day, prisoners were counted at the roll-call plaza at the eastern end of the camp. Growth of the camp was fueled by the Gusen, Kastenhof, and Pierbauer quarries, whose stone was in demand throughout Austria.[13]

SS command

.jpg.webp)

Commandants of Gusen reported directly to Mauthausen commandant SS-Obersturmbannführer Franz Ziereis.[23] The first commandant was Anton Streitwieser, who was dismissed in May 1940 for running an unauthorized pig farm and feeding the pigs with rations siphoned from the supply intended for prisoners.[24] From 25 May 1940 to October 1942[11] or January 1943,[23] the SS commandant was SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Chmielewski, who had been a member of the SS since 1932 and the camp SS since 1935.[25] His Rapportführer (Report Supervisor) was Anton Streitwieser and Kurt Kirchner was the labor service leader.[19] Often drunk,[11] he personally beat, kicked, whipped, and killed prisoners;[25] he had considerable autonomy in running the camp and ensured that life was characterized by violence and sadism.[19] During Chmielewski's rule, one half of prisoners died.[25] From October 1942 until the end of the war, SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Friedrich August Seidler was the commandant.[19][17][23] Seidler preferred "Prussian-style" brutality instead of his predecessor's indiscriminate style.[17] Until 1943, Gusen was run more as a branch of the main camp than as a subcamp, although it had separate administrative departments, such as Political Department.[26]

Initially, the watchtowers, equipped with machine guns and searchlights, were made of wood; later they were replaced by granite. In addition to the barbed-wire fence, an additional stone wall 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high was built around it in 1941; patrols of guards went between the barriers. A third fence, of barbed wire, was added to encircle the entire camp complex, including external factories and quarries. The SS had a separate complex for its own barracks, located outside of the prisoner camp.[13] In February 1940, there were about 600 SS guards (one for each ten prisoners).[27] This later increased to 2,000,[11] and 3,000 by 1944. They belonged to four Camp SS companies, part of SS-Totenkopfsturmbann Mauthausen. In early 1945, many were drafted into the Kampfgruppe Oberdonau and were replaced by Viennese firemen,[23] former Wehrmacht personnel, and Volkssturm militiamen.[28] Nazi human experimentation took place at Gusen, including surgical and tuberculosis experiments.[29] SS physician Helmut Vetter, who arrived in 1944, conducted the tuberculosis experiments by injecting the lungs of healthy prisoners with phlegmonic pus. The victims were then forced to run until they collapsed, at which point they were killed by benzene injection to the lungs, which prolonged death.[18]

Most of the prisoner functionaries, especially block leaders, were German criminal prisoners who were initially picked by Chmielewski.[19][17] Some kapos were notorious for their brutality, including Wolf, a German who executed prisoners by hanging and stamped on the bodies, and the Spaniards Asturias, Félix Domingo, Indalecio González González, Losa, Tomás, and a man called "el Negro".[30] The Austrian kapo Rudolf Fiegl participated in gassing inmates.[31] On Sundays, football teams played on the Appellplatz for SS amusement. Participants were rewarded with extra rations.[32] In 1942, a Nazi camp brothel opened at the camp in order to reduce the number of prisoner functionaries who were tempted to coerce young male inmates into sex.[33][13] At the brothel ten women, all considered "Aryan", were coerced into offering sex in exchange for a false promise of their freedom.[34] Most of them were drafted into a women's Waffen-SS unit in March 1945.[35]

Execution

Some prisoners, no longer capable of hard labor, were sent from Mauthausen to Gusen in order to be killed. At Gusen, the SS forced arriving prisoners to run in order to test their fitness. Those unable to perform the task sufficiently well were immediately killed, a fate that befell 3,000 of the first 10,000 prisoners sent to Gusen. Because they were never registered, these prisoners were not included in the official death statistics.[11][23] After two Polish prisoners, Victor Lukawski and Franc Kapacki, escaped on 13 August 1940, the eight hundred prisoners in their work detail had to run carrying rocks and were beaten by SS guards. Later, they had to stand at attention all night without food. Fourteen Polish prisoners died and so did Lukawski and Kapacki, who were beaten to death a few days later after being caught.[36] Construction on the Gusen crematorium, a double-muffle model built by Topf and Sons, began in December 1940.[21][37] In use from late 1941,[13] the crematorium was under the command of SS-Oberscharführer Karl Wassner.[17]

Either Chmielewski[38] or SS-Hauptscharführer Heinz Jentsch[17] invented a new execution method called Totbaden (death baths). Prisoners unable to work and others the SS wanted to kill were forced to stand under cold showers until they died, which could take twenty minutes to two hours. The drains were blocked and those who tried to avoid the water were drowned. Afterwards, falsified causes of death were entered into the official record.[39][38][40] This execution method was only used at Gusen, and was considered inefficient by SS actuaries. During winter, prisoners were stripped naked and forced to stand outside of Block 32 at night in groups of 150. Typically, half would die before morning and the rest would die the next day.[18]

During the final months of the war, an improvised gas chamber was devised at Gusen in a crudely converted barracks. The number of prisoners who were murdered there is estimated at about 800[41] or more than 1,000.[6] Previously, on 26 March 1942, around 100 Soviet prisoners of war were gassed in Block 16 with Zyklon B.[21] Other prisoners were transported to Mauthausen to be gassed, died in the gas van between Mauthausen and Gusen.[6][41] From early 1942, sick prisoners were selected at Gusen to die at Hartheim Euthanasia Center; 1,100 Gusen prisoners are estimated to have died there.[42] In April 1945, 800 prisoners were beaten to death in Gusen II and transported to Gusen I for cremation.[35] According to the official records, 27,842 people died at Gusen. The actual number is believed to be at least 35,000[43] or more than 37,000.[35] More than 10,000 of these deaths are believed to have occurred in 1945.[44][45]

| 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | Through April 1945 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,522 | 5,570 | 3,890 | 5,116 | 4,004 | 7,740 |

Prisoners

For most of its history (except 1940 and 1943), there were more prisoners in Gusen than in the main camp.[26] Until 1944, its prisoners were inscribed in the register of the main camp.[8] Gusen was initially designated as a "reeducation camp" for Polish members of the intelligentsia. The first transport of Polish prisoners arrived the same day that the camp officially opened. By the end of 1940, eight thousand Poles had been transported to the subcamp—largely from Dachau and Sachsenhausen—and 1,500 had already died.[46][8] The first transport of Republican veterans of the Spanish Civil War arrived on 24 January 1941, and the 3846[39] Spaniards made up most of the arrivals in the first half of 1941. Despite being targeted for excessive punishment by the SS guards—sixty percent died by the end of 1941, mostly in the quarries—the Spanish prisoners gained a reputation for solidarity.[47] Of the more than 4,200 who passed through the camp,[48] only 444 Spaniards were still alive by 1944.[18]

In mid-1941, when Aktion T4 personnel arrived at the camp, most of the prisoners were Poles and Spaniards. Those unable to work were selected for death by T4 staff.[49] In 1941 many Dutch Jews were deported to Mauthausen.[50] None survived.[51] Many Soviet prisoners of war were also deported to Gusen in late 1941 and 1942. Until 1943, by which point 90% had died, they were housed and registered separately from other prisoners.[19] Yugoslavs, Soviet civilians, and a handful of French prisoners (under the Nacht und Nebel decree) arrived from 1942.[21][13] In September 1943, the first Italian prisoners arrived at the camp,[52] where they faced a very high mortality rate.[53] Some Allied aircrew shot down nearby were also imprisoned at the camp.[13] Gusen II, established in 1944, had mostly Soviet and Italian prisoners.[54] The SS encouraged animosity between prisoners of different nationalities.[52] There were no significant resistance groups in Gusen.[55] In 1945, some German and Austrian criminal prisoners were freed by volunteering for the Waffen-SS.[35]

Aircraft production

From 1943,[13] the purpose of the camp was switched from quarrying to armaments production in vast underground factories, to protect the industrial output from Allied bombing. Work on the tunnels was begun by the Kellerbau Kommando at the original Gusen camp, which had a high mortality rate. The tunnels at Gusen were initially used for the production of Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter aircraft.[32] The work took on new urgency after the bombing of the Messerschmitt plant in Regensburg on 17 August 1943.[32][56] Afterwards, 35 per cent of fighter production derived from Gusen and Flossenbürg.[32] By July 1944, 4,000 Gusen prisoners were working on aircraft production, and 77 trainloads of aircraft parts were exported each month.[57] Other prisoners produced rifles, machine guns, and airplane motors for Steyr-Daimler-Puch AG in 16 large warehouses northeast of the original Gusen camp.[22][43]

In the tunnels, prisoners were supervised by Messerschmitt employees (engineers, foremen and skilled workers) who were forbidden to discuss the project with anyone on pain of death. In January 1944, engineer Karl Fiebinger's plans called for 50,000 square metres (540,000 sq ft) of underground floor space in the Bergkristall tunnels (also known as B8 and "Esche 2"), equivalent to 12 acres (4.9 ha), stretching for 22 kilometres (14 mi); the entrance was 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) northwest of the camp. The space was to serve as an underground factory for Messerschmitt 262 jet fighter aircraft, sufficient to produce 1,250 fuselages per month[58][59] along with the entire slat production necessary.[60] Work began on the tunnels in March 1945 and was never completed.[61] Nevertheless, aircraft production began in early 1945 and before 1 May, 987 fuselages were built.[58][59] Most of the manufacturing work, including quality control, was done by prisoners,[57] employed by Messerschmitt via the SS company DEST.[62] During air raids, Austrian civilians were ordered into the tunnels and were separated from the prisoners only by a wooden partition.[35]

Prisoners who worked on arms production needed skills to be effective at their jobs and were therefore less replaceable. Constructing and expanding the tunnels, and speed of construction was valued much higher than prisoners' lives, which had "disastrous" consequences for the prisoners.[22] At first, prisoners had to walk to the Bergkristall, but later a purpose-built railway transported 100 prisoners per cattle car.[54] Prisoners worked for a week in the day shift, and the next week in the night shift. They had to spend up to 14 hours a day in transit or in the tunnels,[63] where the dust was so thick that they had to use headlamps to use pneumatic drills. They were quickly worn out by the dust and lack of oxygen such that 100 died in the tunnels each day.[54]

Subcamps

In 1944, two subcamps of Gusen opened and the main camp was redesignated "Gusen I".[23] Gusen II, which opened on 9 March, was close to the main camp, separated only by a potato field, and also located on the St. Georgen road. Its prisoners—a planned 10,000—were dedicated to arms construction at the Bergkristall;[23][32] others worked for Steyr-Daimler-Puch.[23] At Gusen II, many of the personnel were Luftwaffe guards,[32][59] numbering 2,000 by the war's end.[64] One of the main commandos, Bergkristall-Fertigung, worked for the Luftwaffe while the other, Bergkristall-Bau, for the SS.[32] By the end of 1944, there were 12,000 prisoners at Gusen II.[61]

Gusen III was 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) north, near Lungitz; its 260 prisoners worked in a nearby brick factory and in manufacturing parts for Messerschmitt, in barracks rather than tunnels.[23][58] Some also worked on a project to connect Lungitz to St. Georgen by tunnel. According to testimony, conditions at Gusen III were even worse than the other two subcamps.[54] Both subcamps were under the command of SS-Obersturmführer Max Pausch.[32] Despite the efforts of a dedicated counter-intelligence unit, reports of aircraft production at Gusen II were received by United States intelligence from the Austrian resistance on 3 December 1944.[65]

Liberation

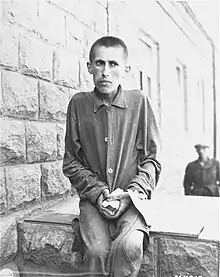

In late January 1944, there were 7,312 prisoners, which increased to 24,250 in all three subcamps at the end of 1944 and decreased to 20,487 by 4 May 1945.[13][26] About 4,000 Warsaw Uprising prisoners were sent to Gusen in late 1944 and additional inmates arrived due to the evacuation of concentration camps in early 1945 as Allied armies approached. By the end of March, there were about 24,000 prisoners in the three Gusen camps. In April, additional prisoners were transferred to Gusen from subcamps closer to the front line.[66] Many prisoners had become Muselmänner (emaciated), many suffered from typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis, or pneumonia, and some lacked clothes. Overcrowding meant that there were three people to a bunk, and conditions were even worse in Block 31, where those suffering from dysentery were thrown on the floor and denied food.[35]

In April 1945, Ziereis contemplated murdering the 40,000 prisoners at Gusen by trapping them in the tunnels and detonating them with dynamite.[67] He passed the order on to Seidler and an ammunition depot was set up nearby by 28 April. Two of the five entrances of the Sandkeller tunnels at Gusen I were walled off and explosives placed at the entrances of the Kellerbau and Bergkristal tunnels.[68] This "murderous brainstorming", in the words of historian Daniel Blatman, was never carried out due to the collapse of Nazi authority.[67] Individual SS members began to desert in large numbers on the night of 2–3 May. More SS left the camp in groups on 3 May 1945, with the pretext of fighting the Soviet army, although most, in fact, hid in the surrounding woods and hills.[69] Over the next day, the prisoners gradually realized that they were free;[70] able-bodied prisoners left the camp.[71] Most of the SS had left by the time elements of the United States 11th Armored Division arrived in the early morning of 5 May.[23][72][73]

Staff Sergeant Albert J. Kosiek, in charge of a platoon in the 41st Cavalry Squadron, was ordered to investigate a suspected enemy strongpoint near Mauthausen, and to check the bridge near Gusen which was intended to be used by American tanks. He first reached Gusen III, where the newly recruited guards, formerly firemen from Vienna, were very willing to surrender. Only two American soldiers were left behind to escort them to the American brigade's headquarters. North of St. Georgen, Kosiek encountered a Red Cross representative who told him that there was a concentration camp at Mauthausen and 400 SS who wanted to surrender. Because he did not have enough men to accept the SS surrender, Kosiek tested the bridge and bypassed Gusen II and Gusen I on the way to Mauthausen.[74] Over the next twenty-four hours, the remaining SS burned all documents relating to the Messerschmitt 262 in the Gusen crematorium. Kosiek accepted the surrender of the 800 SS at Gusen while returning to headquarters the next day.[75] More American forces arrived at Gusen later the same day. They found a situation of complete chaos, as prisoners killed each other with weapons abandoned by the fleeing SS. Many of the sickest prisoners had been sealed in barracks without food or water; when the American soldiers opened them it was rare to find more than one or two still alive. A group of kapos responsible for atrocities barricaded themselves in Block 32. Some committed suicide while others were torn apart by the mob.[76]

Corpses after liberation

Corpses after liberation Bodies are removed by Austrian citizens

Bodies are removed by Austrian citizens Three Mauthausen Trial defendants

Three Mauthausen Trial defendants

Aftermath

.jpg.webp)

Following the liberation, some former kapos were killed by surviving inmates.[77] Although German-speaking prisoners who had angered the numerically dominant Poles were at most risk of lynching,[76] most prisoners were more interested in obtaining food than revenge, and most kapos escaped unmolested and were never held to account for their crimes.[78] Russian and Polish prisoners attacked each other and had to be forcibly separated.[79] In the next several weeks, local Austrians lived in fear of renegade SS, bands of maurading kapos, and former prisoners.[80] On 8 May, Nazi party members were ordered to bury the dead in the potato field between Gusen I and II while local citizens were forced to watch.[81] On 27 July 1945, American troops retreated from the area according to the Yalta Agreement, taking with them all the unfinished aircraft from the tunnels. The remaining prisoners who were too weak to move were put in the charge of the Soviet occupation forces.[82]

At least 16 former guards and kapos were convicted during the Mauthausen Trial at Dachau.[23] Former kapo Rudolf Fiegl was convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged for gassing prisoners,[31] as was the SS doctor Vetter.[83] Chmielewski escaped the first trial and lived in Austria under false papers. In 1956 he was recognized and arrested. Following a 1961 trial[84] in which he was convicted of 282 murders, he was sentenced to life in prison.[23][38] Jentsch, involved in the "death baths", was arrested in West Germany, tried in Hagen in 1967, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.[84] More than 70 criminal investigations were opened by West German prosecutors.[23]

The former site of Gusen I and II was redeveloped into a village and most of the concentration camp buildings were demolished.[85] As of 2017, the Poschacher quarry adjacent to Gusen I was still in use, the former Bergkristall tunnels are privately owned and not open to the public, as is the entrance to Gusen I.[86] The memorial at Gusen, privately built, was acquired by the government in 1997 which has since maintained it and also built a small museum nearby in 2004.[85][87] In the 2010s, local municipalities around Mauthausen and Gusen set up a Bewußtseinsregion ("consciousness region") in order to promote preservation and restoration of the sites. In 2013, two archaeologists conducted rescue archaeology at the former Gusen crematorium.[88] In late 2019 and early 2020, the Polish government suggested that the Gusen village should be bought and additional efforts made to commemorate the victims of the camp. In January 2020, the Austrian government announced that it was setting aside EU€2 million (USD$2.2 million) to that end.[87]

References

- Lichtblau 2015, pp. 41–42.

- Lichtblau 2015, pp. 46–47.

- Lichtblau 2015, pp. 48–49.

- Waite 2009, p. 900.

- Wachsmann 2015, pp. 210, 343.

- Lechner & Dürr 2009, p. 905.

- Jaskot 2002, pp. 35, 43.

- Perz 2006, p. 371.

- Pike 2003, pp. 94–95.

- Waite 2009, p. 919.

- Pike 2003, p. 90.

- Jaskot 2002, p. 43.

- Waite 2009, p. 920.

- Wachsmann 2015, pp. 452–453.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 451.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 437.

- Pike 2003, p. 91.

- Pike 2003, p. 92.

- Perz 2006, p. 372.

- Freund & Kranebitter 2016, pp. 58–59.

- Perz 2006, p. 373.

- Freund & Kranebitter 2016, p. 62.

- Waite 2009, p. 921.

- Pike 2003, p. 52.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 495.

- Freund & Kranebitter 2016, p. 58.

- Pike 2003, p. 29.

- Pike 2003, p. 182.

- Pike 2003, p. 14.

- Pike 2003, p. 58.

- Pike 2003, pp. 91, 348.

- Pike 2003, p. 93.

- Pike 2003, p. 311.

- Pike 2003, p. 67.

- Pike 2003, p. 181.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 494.

- Mitchell 2017, p. 562.

- Lewy 2017, p. 25.

- Pike 2003, pp. 91–92.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 539.

- Pike 2003, p. 102.

- Perz 2006, pp. 372–373.

- Waite 2009, pp. 920–921.

- Perz 2006, p. 377.

- "Gusen". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- Wachsmann 2015, pp. 494–495.

- Wachsmann 2015, pp. 497–498.

- Perz 2006, p. 379.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 530.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 772.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 45.

- Pike 2003, p. 65.

- Pike 2003, p. 316.

- Pike 2003, p. 94.

- Pike 2003, p. 155.

- Uziel 2011, p. 215.

- Uziel 2011, p. 191.

- Pike 2003, pp. 93–94.

- Uziel 2011, pp. 190–191.

- Uziel 2011, p. 135.

- Uziel 2011, pp. 134–135.

- Uziel 2011, p. 134.

- Uziel 2011, p. 219.

- Pike 2003, p. 185.

- Pike 2003, p. 184.

- Blatman 2011, p. 214.

- Blatman 2011, p. 212.

- Pike 2003, pp. 181–182.

- Pike 2003, p. 196.

- Stone 2015, p. 80.

- Pike 2003, p. 219.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 1202.

- Pike 2003, p. 198.

- Pike 2003, pp. 218–219.

- Pike 2003, p. 223.

- Pike 2003, p. 239.

- Stone 2015, pp. 100, 103.

- Pike 2003, p. 229.

- Pike 2003, p. 251.

- Pike 2003, p. 228.

- Pike 2003, p. 243.

- Pike 2003, pp. 253, 275.

- Pike 2003, p. 269.

- Pike 2003, p. 271.

- Mitchell 2017, p. 569.

- Pike 2003, p. 278.

- Jankowiak, Celine; Gauquelin, Blaise (25 January 2020). "Poland pushes for Nazi camp in Austria to be remembered". Times of Israel. AFP. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Mitchell 2017, p. 570.

- Sources

- Blatman, Daniel (2011). The Death Marches. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674059191.

- Freund, Florian; Kranebitter, Andreas (2016). "On the Quantitative Dimension of Mass Murder at the Mauthausen Concentration Camp and its Subcamps". Memorial Book for the Dead of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp: Commentaries and Biographies. Vienna: New Academic Press. pp. 56–67. ISBN 978-3-7003-1975-7.

- Jaskot, Paul B. (2002). The Architecture of Oppression: The SS, Forced Labor and the Nazi Monumental Building Economy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 9781134594610.

- Lechner, Ralf; Dürr, Christian (2009). "Mauthausen subcamp system". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. 1. Translated by Pallavicini, Stephen. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 905–907. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Lewy, Guenter (2017). Perpetrators: The World of the Holocaust Killers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-066115-1.

- Lichtblau, Albert (2015). "Austria". In Gruner, Wolf; Osterloh, Jörg (eds.). The Greater German Reich and the Jews: Nazi Persecution Policies in the Annexed Territories 1935–1945. War and Genocide. Translated by Heise, Bernard. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 39–67. ISBN 978-1-78238-444-1.

- Mitchell, Paul (2017). "Concentration Camp Buildings as Artifacts: The Archaeology of Buildings in the Mauthausen-Gusen Complex". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 22 (3): 553–573. doi:10.1007/s10761-017-0439-9. S2CID 148713208.

- Perz, Bertrand (2006). "Gusen I und II". In Benz, Wolfgang (ed.). Flossenbürg, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück. Der Ort des Terrors (in German). 4. Munich: C. H. Beck. pp. 371–379. ISBN 978-3-406-52964-1.

- Perz, Bertrand (2006). "Gusen III". In Benz, Wolfgang (ed.). Flossenbürg, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück. Der Ort des Terrors (in German). 4. Munich: C. H. Beck. pp. 380–381. ISBN 978-3-406-52964-1.

- Pike, David Wingeate (2003). Spaniards in the Holocaust: Mauthausen, Horror on the Danube. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-58713-1.

- Stone, Dan (2015). The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21603-5.

- Uziel, Daniel (2011). Arming the Luftwaffe: The German Aviation Industry in World War II. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 9780786488797.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015). KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780374118259.

- Waite, Robert G. (2009). "Mauthausen main camp". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 900–903. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Waite, Robert G. (2009). "Gusen". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 919–921. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

Further reading

- Maršálek, Hans (1987). Konzentrationslager Gusen: ein Nebenlager des KZ Mauthausen (in German). Vienna: Österreichische Lagergemeinschaft Mauthausen. OCLC 36413887.

- Orski, Marek (2004). Gusen 2004: The Past and the Present. Gdánsk: Wydawnictwo Gdańskie. ISBN 978-83-88836-70-1.

- Witzany-Durda, Siegi (2002). "Die Konzentrationslager Gusen I, II, III". In Bachl, Gottfried; Scheuer, Manfred (eds.). Ge-Denken: Mauthausen/Gusen - Hartheim - St. Radegund (in German). Linz: Edition Kirchen-Zeit-Geschichte. pp. 13–53. OCLC 260009524.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gusen concentration camp. |

- Gusen Memorial Committee (GMC) Website

- Audiowalk Gusen

- Testimony of Jewish Gusen II survivor Ze'ev Weiszner

- Scenes about the liberation of the Gusen and Mauthausen twin complex in May 1945 narrated first hand by liberator S/Sgt. Rtd. Raymond S. Buch, 11th Ard Div (2017)

- Scenes from inside the gigant "Bergkristall" underground memorial of Camp Gusen II at St. Georgen (2015)

- Lecture by Jan-Ruth Mills "Landscape and Denial: Restoring Memory to Images of KZ Gusen" (2012)