HMS Collingwood (1882)

HMS Collingwood was the lead ship of her class of ironclad battleships built for the Royal Navy during the 1880s. The ship's essential design became the standard for most of the following British battleships. Completed in 1887, she spent the next two years in reserve before she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet for the next eight years. After returning home in 1897, the ship spent the next six years as a guardship in Ireland. Collingwood was not significantly damaged during an accidental collision in 1899 and was paid off four years later. The ship was sold for scrap in 1909 and subsequently broken up.

HMS Collingwood at anchor | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Collingwood |

| Namesake: | Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood |

| Builder: | Pembroke Dockyard |

| Laid down: | 12 July 1880 |

| Launched: | 22 November 1882 |

| Completed: | July 1887 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 11 May 1909 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Admiral-class ironclad battleship |

| Displacement: | 9,500 long tons (9,700 t) |

| Length: | 325 ft (99.1 m) (p.p.) |

| Beam: | 68 ft (20.7 m) |

| Draught: | 26 ft 11 in (8.2 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 16.8 kn (31.1 km/h; 19.3 mph) (forced draught) |

| Range: | 8,500 nmi (15,700 km; 9,800 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 498 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

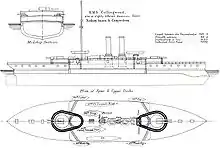

Background and design

At the time of her design, she was not considered as being the forerunner of any class; she was designed by the Director of Naval Construction, Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, as a one-off as an answer to the French Amiral Baudin-class ironclads, which carried three heavy guns on the centreline and a number of smaller pieces on the broadside. He made several proposals to the Board of Admiralty, but they were all rejected.[1] Barnaby's final submission was inspired by the four French Terrible-class ironclads laid down in 1877–78 and was a return to the configuration of Devastation with the primary armament positioned fore and aft of the central superstructure, but with the breech-loading main armament mounted in barbettes, as per the French ships,[2][3] which allowed them to be sited 10 feet (3.0 m) further above the waterline than Devastation's guns.[4] The Board modified Barnaby's design by adding 25 feet (7.6 m) of length and 2,000 indicated horsepower (1,500 kW) to guarantee a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) at deep load. It also substituted four smaller 42-long-ton (43 t) guns for Barnaby's two 80-long-ton (81 t) guns. The additional length and the Board's acceptance of the hull lines from Colossus increased the size of the ship by 2,500 long tons (2,540 t).[5]

Barnaby was severely criticised, particularly by Sir Edward Reed, himself a former Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy, because Collingwood's waterline armour belt was concentrated amidships and did not extend to the ends of the ship. Reed believed that this weakness meant that the ship could be sunk from the consequent uninhibited flooding if her unarmoured ends were riddled by shellfire and open to the sea. Barnaby deliberately selected a hull shape with narrow, fine ends to limit the volume of the hull that could be flooded and situated the armoured deck below the waterline to prevent it from being pierced by enemy shells and flooding the lower part of the ironclad. Furthermore, he heavily subdivided the hull to limit the amount of water that could enter through any one hit and placed coal bunkers above the armoured deck to absorb the fragments from exploding shells. Unbeknownst to his critics, Collingwood was tested in 1884 with her ends and the large spaces in her hold ballasted with water and her draught only increased by 17.5 inches (440 mm) and she lost a minor amount of speed. The price was that the ship lacked buoyancy at her ends and tended to bury her bow in oncoming waves rather than be lifted over them. Her speed was greatly reduced in a head sea and the resulting spray made working the guns very difficult. Collingwood tended to roll heavily and was not regarded as a good seaboat. Despite these issues, her basic configuration was followed by most subsequent British ironclads and predreadnought battleships until the revolutionary Dreadnought of 1905.[6]

The ship had a length between perpendiculars of 325 feet (99.1 m), a beam of 68 feet (20.7 m), and a draught of 27 feet 10 inches (8.5 m) at deep load. She displaced 9,500 long tons (9,700 t) at normal load[3] and had a complement of 498 officers and ratings.[7]

The ship was powered by a pair of 2-cylinder inverted compound-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller. The Humphreys engines produced a total of 7,000 indicated horsepower (5,200 kW) at normal draught and 9,600 ihp (7,200 kW) with forced draught, using steam provided by a dozen cylindrical boilers with a working pressure of 100 psi (689 kPa; 7 kgf/cm2).[7] She was designed to reach a speed of 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h; 17.8 mph) at normal draught and Collingwood reached 16.6 knots (30.7 km/h; 19.1 mph) from 8,369 ihp (6,241 kW) on her sea trials, using natural draught. She was the first British ironclad to be equipped with forced draught and the ship only reached a speed of 16.84 knots (31.19 km/h; 19.38 mph) from 9,573 ihp (7,139 kW) while using it during her sea trials because her engines were incapable of handling the additional steam.[8] Collingwood carried a maximum of 1,200 long tons (1,219 t) of coal that gave her a range of 8,500 nautical miles (15,700 km; 9,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[9]

Armament and armour

The ship had a main armament of 25-calibre rifled breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mk II guns. The four guns were mounted in two twin-gun barbettes, one forward and one aft of the superstructure. The barbettes were open, without hoods or gun shields, and the guns, mounted on a turntable, were fully exposed. They could only be loaded when pointed fore and aft with an elevation of 13°. The 714-pound (324 kg) shells fired by these guns were credited with the ability to penetrate 20.6 inches (523 mm) of wrought iron at 1,000 yards (910 m),[10] using a charge of 295 pounds (134 kg) of prismatic brown powder. At maximum elevation, the guns had a range of around 9,400 yards (8,600 m).[11]

The secondary armament of Collingwood consisted of six 26-calibre BL 6-inch (152 mm) Mk IV guns on single mounts positioned on the upper deck amidships, three on each broadside. They fired 100-pound (45 kg) shells that were credited with the ability to penetrate 10.5 inches (267 mm) of wrought iron at 1000 yards.[10] They had a range of 8,830 yards (8,070 m) at an elevation of +15° using prismatic black powder. Beginning around 1895 all of these guns were converted into quick-firing guns (QF) with a much faster rate of fire. Using cordite extended their range to 9,275 yards (8,481 m).[12] For defence against torpedo boats the ships carried a dozen QF 6-pounder 2.2-inch (57 mm) Hotchkiss guns and eight QF 3-pdr 1.9-inch (47 mm) Hotchkiss guns. They also mounted four 14-inch (356 mm) above-water torpedo tubes, one pair on each broadside.[3]

Collingwood's waterline belt of compound armour extended across the middle of the ship between the rear of each barbette for a the length of 140 feet (42.7 m). It had a total height of 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 m) deep of which 5 feet (1.5 m) was below water and 2 feet 6 inches (0.8 m) above at normal load; at deep load, the ship's draught increased by another 6 inches. The upper 4 feet (1.2 m) of the belt armour was 18 inches (457 mm) thick and the plates tapered to 8 inches (203 mm) at the bottom edge. Lateral bulkheads at the ends of the belt connected it to the barbettes; they were 16 inches (406 mm) thick at main deck level and 7 inches (178 mm) below.[13]

Each barbette was a roughly pear-shaped, 11-sided polygon, 60 by 45 feet (18.3 m × 13.7 m) in size with sloping walls 11.5 inches (292 mm) thick and a 10-inch (254 mm) rear. The main ammunition hoists were protected by armoured tubes with walls 10–12 inches thick.[4] The conning tower also had 12-inch thick walls as well as roofs 2 inches (51 mm) thick. The deck of the central armoured citadel had a thickness of 3 inches (76 mm) and the lower deck was 2–2.5 inches (51–64 mm) thick from the ends of the belt to the bow and stern.[4][9]

Construction and career

Collingwood, named after Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, Horatio Nelson's second-in-command in the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar,[14] was the second ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy.[15] The ship was laid down at Pembroke Dockyard on 12 July 1880[9] and launched by Mrs. Louise Chatfield, wife of the dockyard's Captain-Superintendent, Captain Alfred Chatfield,[16] on 22 November 1882.[9] While conducting gunnery trials on 4 May 1886, Collingwood's rear left gun partially shattered and all of the Mk II guns were withdrawn from service. They were replaced by heavier Mk Vw models with approximately the same performance.[11] Excluding her armament, she cost £636,996. The ship was commissioned at Portsmouth on 1 July 1887 for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee Fleet review and was paid off into reserve in August.[17]

Collingwood was recommissioned for the annual summer manoeuvres for the next two years, before she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, where she served from November 1889 until March 1897, with a refit in Malta in 1896.[17] Captain Charles Penrose-Fitzgerald commanded the ironclad when she joined the Mediterranean Fleet in 1889.[18] The ship became the coastguard ship at Bantry, Ireland, upon her return.[17] Collingwood accidentally collided with the cruiser HMS Curacoa in Plymouth harbour on 23 January 1899, badly damaging the latter ship, but was not significantly damaged herself.[19] She took part in the fleet review held at Spithead on 16 August 1902 for the coronation of King Edward VII,[20] and was back in Ireland later that month when she received the Japanese cruisers Asama and Takasago to Cork.[21] The ship was paid off into the reserve in June 1903 and was transferred to East Kyle in January 1905. Collingwood remained there until she was sold for scrap[17] to Hughes Bolckow at Dunston, Tyne and Wear[9] for £19,000[17] on 11 May 1909.[14]

Notes

- Brown, p. 91

- Beeler, pp. 161–62

- Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 29

- Parkes, p. 302

- Beeler, pp. 164–66

- Brown, pp. 92–93; Parkes, pp. 300, 303, 305–306

- Parkes, p. 301

- Brown, p. 94

- Winfield & Lyon, p. 258

- Parkes, p. 316

- Campbell 1981, p. 202

- Campbell 1983, pp. 171–72

- Parkes, p. 303

- Silverstone, p. 223

- Colledge, p. 74

- Phillips, pp. 225, 326

- Parkes, p. 304

- Phillips, p. 225

- The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad for the Year 1899. London: Longmans, Green & Co. 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "The Coronation - Naval Review". The Times (36845). London. 13 August 1902. p. 4.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36852). London. 21 August 1902. p. 8.

References

- Beeler, John (2001). Birth of the Battleship: British Capital Ship Design 1870-1881. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-213-7.

- Brown, D.K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1981). "British Naval Guns 1880–1945 No. 3". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship V. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 200–02. ISBN 0-85177-244-7.

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1983). "British Naval Guns 1880–1945 No. 10". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship VII. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 170–72. ISBN 0-85177-630-2.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Phillips, Lawrie; Lieutenant Commander (2014). Pembroke Dockyard and the Old Navy: A Bicentennial History. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5214-9.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Winfield, R.; Lyon, D. (2004). The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-032-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Collingwood. |