Hagia Irene

Hagia Irene or Hagia Eirene (Byzantine Greek: Ἁγία Εἰρήνη Greek pronunciation: [aˈʝia iˈrini], "Holy Peace", Turkish: Aya İrini), sometimes known also as Saint Irene, is an Eastern Orthodox church located in the outer courtyard of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. It is one of the few churches in Istanbul that has not been converted into a mosque, as it was used as an arsenal for storing weapons until the 19th century.[1] The Hagia Irene today operates as a museum and concert hall.

| Hagia Irene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Eastern Orthodox |

| Status | Museum |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

Shown within Istanbul Fatih | |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°0′35″N 28°58′52″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 532 |

| Materials | Brick, Stone |

| Website | |

| https://muze.gen.tr/ | |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th session) |

History

Naming

The church was dedicated to the peace of God, and is one of the three shrines which emperors devoted to God's attributes, together with Hagia Sophia (Wisdom) and Hagia Dynamis.[2]

Church architecture

The building reputedly stands on the site of a pre-Christian temple. It ranks as the first church completed in Constantinople, before Hagia Sophia, during its transfiguration from a Greek trading colony to the eastern capital of the Roman Empire. According to later tradition, the Roman emperor Constantine I commissioned the first Hagia Irene church in the 4th century, which was completed by the end of his reign (337). It served as the church of the Patriarchate before Hagia Sophia was completed in 360 under Constantius II.[3] During the Nika revolt in 532,[4] Hagia Irene was burned down. Emperor Justinian I had the church rebuilt in 548. It was then damaged again by the 740 Constantinople earthquake on October 20, 740, about six months before the death of Leo III.[5] The Emperor Constantine V ordered the restorations[5] and had its interior decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Some restorations from this time have survived to the present.

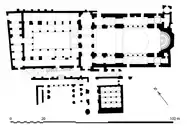

Reconstruction during the reign of Justinian I shows change in the architecture of the atrium and narthex, which stayed intact after the earthquake. Restoration after the earthquake created a stronger foundation for the church.[5] Before being rebuilt, the foundation had significant structural problems.[5] This restoration established a cross-domed plan on the gallery level while still being able to keep the original basilica plan at the ground level.[5] The narthex can be found to the west, preceded by the atrium, and then the apse on the east side.[5] Hagia Irene still holds its dome and has peaked roofs on the north, west, and south sides of the church.[5] The dome itself is 15m wide and 35m high and has twenty windows. Hagia Irene has the typical form of a Roman basilica, consisting of a nave and two aisles, which are divided by three pairs of piers.[5] This helps support the galleries above the narthex.[5] Semicircular arches are also attached to the capitals which also helps give support to the galleries above.[5]

Art inside the church

In Byzantine tradition, there is a unique vestige of the Iconoclastic art within the church. The apse semidome and the bema arch are covered with mosaics.[5] There are also the frescoes which can be found on the south side aisle.[6] These mosaics date back to about the 8th century. This was during the time of the earthquake which most of the upper parts of the church can date back to.[7] There is also a mosaic of a cross, which is outlined in black with a gold background.[5] The ends are flared along with having teardrop shapes at the end. This extends around the base of the semidome.[5] The cross was put in during the reconstruction by Constantine V, which was during the Iconoclastic years.[6] On the bema arch there is an inscription of Psalm 64 verses 4–5 on the inner side, and then on the outer side there is an inscription of Amos 6 verse 6. There is evidence of alterations on these inscriptions as well.[5] The inscriptions detail a praise to the church as it is the house of the lord.[6] The verses, especially the Psalm, were used as inspiration for some of the mosaics in Hagia Sophia.[6]

Hagia Irene also holds a synthronon. Synthronons are rows of built benches that are arranged in a semicircle in the apse. During Divine Liturgy this is where the clergy would sit.[6] This is the only synthronon that has survived in the city from the Byzantine era.[5] The synthronon in Hagia Irene has six tiers of seats. There are doors at both side that open up into an ambulatory beneath the fourth tier of seats.[5]

Cross on the dome

The cross on top of the dome has been replaced by the conquering Ottomans with the symbol of Turkish Islam, the crescent moon.

Arsenal

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, the church was enclosed inside the walls of the Topkapi palace. The Janissaries used the church as an arsenal (Cebehane) until 1826.[8] It was also used as a warehouse for military equipment and repository for trophies of arms and military regalia taken by the Turks.[8] During the reign of Sultan Ahmet III (1703–1730) it was converted into the National Military Museum in 1726.[8]

In 1846, Marshal of the Imperial Arsenal, Ahmed Fethi Paşa, made the church a military antiques museum.[9] It was used as the Military Museum from 1908 until 1978 when it was then turned over to the Turkish Ministry of Culture.

Concert hall

Today, the Hagia Irene serves mainly as a concert hall for classical music performances, due to its extraordinary acoustic characteristics and impressive atmosphere. Many of the concerts of the Istanbul International Music Festival have been held here every summer since 1980.

In 2000, the Turkish haute couture designer Faruk Saraç produced a special show here. A collection of 700 designed pieces inspired by the Ottoman sultans, including the robes of 36 sultans ranging from Osman Gazi, the founder of the Ottoman Empire to the last sultan, Mehmed VI, were on display. The show was accompanied by music and the story of the sultans' lives and demonstrations of Ottoman-era dancing.

For many years, the Hagia Irene was only accessible during events or by special permission, but the museum has been open to the public every day except Tuesday since January 2014.[10]

Gallery

- Hagia Irene

The apse of the church with cross

The apse of the church with cross Ground plan of the church

Ground plan of the church Ottoman helmet, with markings of Saint-Irene arsenal, Constantinople, circa 1520. Musée de l'Armée.

Ottoman helmet, with markings of Saint-Irene arsenal, Constantinople, circa 1520. Musée de l'Armée. Hagia Irene with Hagia Sophia at the back

Hagia Irene with Hagia Sophia at the back Church of St Irene roof from afar

Church of St Irene roof from afar Church of St Irene exterior from west

Church of St Irene exterior from west Church of St Irene exterior

Church of St Irene exterior Church of St Irene exterior

Church of St Irene exterior Church of St Irene exterior

Church of St Irene exterior Church of St Irene interior

Church of St Irene interior Church of St Irene interior

Church of St Irene interior Church of St Irene apse

Church of St Irene apse Church of St Irene interior

Church of St Irene interior Church of St Irene narthex

Church of St Irene narthex Church of St Irene narthex

Church of St Irene narthex Church of St Irene atrium seen from narthex

Church of St Irene atrium seen from narthex Church of St Irene atrium

Church of St Irene atrium Church of St Irene interior

Church of St Irene interior Church of St Irene capital

Church of St Irene capital

See also

References

- "History". Askeri Müze ve Kültür Sitesi Komutanlığı. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Janin, pg. 106

- Charles Matson Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2010), 237–39.

- Allan Doig, Liturgy and Architecture: From the Early Church to the Middle Ages, (Ashgate Publishing, 2008), 65.

- Freely, John; Cakmak, Ahmet (2004). Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–143. ISBN 978-0521772570.

- "Great Online Encyclopaedia of Constantinople". constantinople.ehw.gr. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- Kazhdan, Alexander P. (1991). Irene, Church of Saint – Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001. ISBN 9780195046526.

- Pyhrr, Stuart (1989). "European Armor from the Imperial Ottoman Arsenal". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 24: 85–116. doi:10.2307/1512872. JSTOR 1512872. S2CID 191412421.

- Museums and Narratives of Display from the late Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, Wendy Shaw, Muqarnas, Vol.XXIV, (Brill, 2007), 256.

- "Hagia Irene Museum Opened". Topkapi Palace Museum. 6 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

Bibliography

- Akşit, I. (2005). Hagia Sophia: Akşit Kültür ve Turizm Yayincilik. ISBN 978-975-7039-07-5.

- Bogdanovic Jelena, "Hagia Eirene", 2008, Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople

- Davis, Fanny (1970). Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul. ASIN B000NP64Z2.

- Freely, John; Cakmak, Ahmet (2004). Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–143. ISBN 0521772575

- "Irene, Church of Saint – Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-2506.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). "Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique". La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines. 3rd Vol.: Les Églises et les Monastères (part 1).

- Kazhdan (ed.), Alexander (1991). "Church of Saint s.v.Irene". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. 2nd of 3 vols. ISBN 978-0195046526.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Krautheimer, Richard (1984). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05294-7.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (1991). Architecture, ceremonial, and power: The Topkapi Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-14050-8.

- Millingen, Alexander Van, Ramsey Traquair, Walter S. George, and Arthur e. Henderson. Byzantine churches in Constantinople: their history and architecture. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1912. Print.

- Musilek, Josef, Lubos Podolka, and Monika Karkova, "The Unique Construction of the Church of Hagia Irene in Istanbul for The Teaching of Byzantine Architecture." Priced Engineering, 161 (2016): 1745–750. Web.

- Pyhrr, Stuart (1989). "European Armor from the Imperial Ottoman Arsenal". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 24: 85–116 JSTOR 1512872

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hagia Irene. |