Hanfu movement

The hanfu cultural movement (simplified Chinese: 汉服文化运动; traditional Chinese: 漢服文化運動) is a cultural movement seeking to revitalize traditional Han Chinese fashion that developed in China at the beginning of the 21st century. It is part of the broader series of ongoing social and cultural rebirth of traditional Han Chinese culture, history, and civilization.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Background

When the Manchus from the Northeast of Ming established the Qing dynasty in 1636, the authorities issued decrees having Han Chinese men to adopt Manchu hairstyle by shaving their entire head while leaving braiding on the back into pigtails and banned the clothing attire wore by contempory Han Chinese as part of series of cultural revisional order. The resistances against these policies were strong. Many loyalists from the Ming had either chose to suiside and die in honorable way or to rebel against the policies. [8] Han Chinese were then executed for refusing to follow the decree. It was until later in the early 20th century that the crippling of Qing Empire and revolutionary thoughts from the west had brought this decree to an end. [9] Koxinga, a Ming loyalist who found Southern Ming (南明) in modern day Taiwan, strongly criticized the Qing hairstyle by referring to the shaven pate as a fly and kept the attire of traditional Han Chinese people.[10] When the Southern Ming finally breached in 1662, all remaining Han Chinese were forced to wear Manchu clothing with braids on their back.

Though not all aspects of Manchu attire were initially enforced upon Han Chinese, the combination of hair and clothing policies have made small characteristic items obsolete by practicality. Gradually the shift in political connotation associated with the traditional Han Chinese clothing culture have made wearing of them as a commoner more difficult.

Nevertheless, the memory of Han Chinese clothing and hair tradition did not completely disappear. In 2006, scholars have excavated Qing Kangxi era corpse in Beijing of a government official with traditional Han Chinese hair style. It was later deduced that his family remade his hair to honor him with grace. [11]

History

During the Qing Dynasty, variants of the Hanfu remained as uniforms of Taoist monks and costumes of Chinese opera. Hanfu as formal attire was briefly revived when Yuan Shikai, the second Provisional Great President of the Republic of China, declared himself the Hongxian emperor in 1916 and adopted Hanfu imperial robes. However, the attempt at reviving Hanfu collapsed when Yuan died in June of that same year.

According to Asia Times Online, the hanfu movement may have begun around 2003. [12] Wang Letian from Zhengzhou, China, publicly wore hanfu. He and his followers inspired others to reflect on the cultural identity of Han Chinese. They organized the hanfu movement as an initiative in a broader effort to stimulate a Han Chinese cultural renaissance.[13] In the same year of 2003, supporters of Han revivalism launched the website Hanwang (Chinese: 漢網) to promote traditional Han clothing, however some sources claim this to be alongside a Han supremacist agenda.[5]

In February 2007, advocates of hanfu submitted a proposal to the Chinese Olympic Committee to have it be the official clothing of the Chinese team in the 2008 Summer Olympics.[14] The Chinese Olympic Committee rejected the proposal in April 2007.[15]

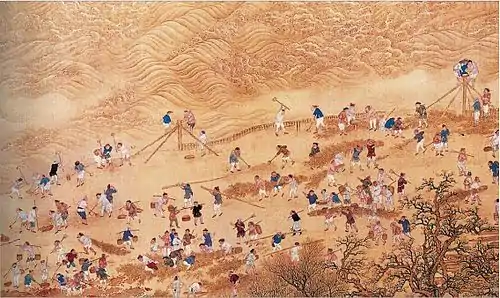

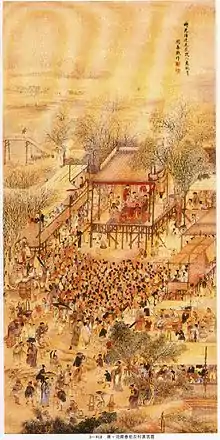

In September 2018, renowned Zhuangshu Fuyuan (Chinese: 裝束復原) team in China appeared on popular Television Channel Hunan Television's (Chinese: 湖南衛視) Tiantian Xiangshang (Chinese: 天天向上) evening program. The team performed reconstructions of traditional court dance in Han Chinese clothing based on historical paintings and frescos in Mo Gao Ku, Dunhuang and demonstrated unique characteristics of each period of clothing. The hosts were dressing in traditional Han Chinese robes as well.

In 2021, Hanfu are much more accepted by general public in China where gatherings and photoshoots wearing Hanfu become common. Many celebrities, including Li Ziqi and Shiyin from Tiktok, wear Hanfu in video and gained massive followings from fans all over the world.

Definition of hanfu

According to Dictionary of Old Chinese Clothing (Chinese: 中國衣冠服飾大辭典), the term hanfu means "dress of the Han people."[16] This term, which is not commonly used in ancient times, can be found in some historical records from Han, Tang, Song, Ming and Qing dynasties and the Republican era in China.[17][18][19][20][21]

Critics have contended that the term hanfu is a modern development. An article published by Chinese Newsweek in September 2005 reported that it is not included in the authoritative dictionary of Standard Mandarin Chinese "Contemporary Chinese Dictionary" (Chinese: 現代漢語詞典) and that it was coined by Internet users around the year 2003.[22]

Professor of China Youth University of Political Studies Zhang Xian (Chinese: 張跣) asserts that hanfu is a modern concept publicized by student advocates of the hanfu movement who created a standard of pre-Qing Han Chinese fashion without accurate academic research and propagated it on collaborative, web-based encyclopedias such as Baidu Baike and Hanwang.[23]

Chinese researcher Hua Mei (Chinese: 華梅), interviewed by student advocates of the hanfu movement in 2007, recognizes that defining hanfu is no simple matter, as there was no uniform style of Chinese fashion throughout the millennia of its history. Because of its constant evolution, she questions which period's style can rightly be regarded as traditional. Nonetheless, she explains that hanfu has historically been used to broadly refer to indigenous Chinese clothing in general. Observing that the apparel most often promoted by the movement are based on the Han-era quju and zhiju, she suggests that other styles, especially that of the Tang era, would also be candidates for revival in light of this umbrella definition.[24]

Professor of Aichi University, cultural anthropologist Zhou Xing (Chinese: 周星) maintains that the term hanfu was not commonly used in ancient times and refers to the traditional costume as imagined by participants of the hanfu movement. Like Hua, he notes that the term hanfu classically referred to clothing that Han people wore in general, but in contrast, he argues that, on this basis, it is not the same as the hanfu as defined by participants of the movement.[25][26]

Influence

Besides inspiring rediscovery and revival on pre-Qing Dynasty Han Chinese garments, Hanfu movement has spurred a series of revived interest in Traditional Chinese Armor (especially Ming armor) and Ancient Chinese weapories like Jian (sword). More traditional cultures and arts like ceremonial music and court music from the Tang Dynasty are becoming popular on many Chinese and oversea streaming platforms like Bilibili and YouTube. Such rekindled interests in Han Chinese culture are also increasingly more connected to serious studies, both domestic and international, and are becoming more organized.

To put Hanfu movement with its society, some supporters of the movement describe it with reference to Renaissance in the 15th century, which carried similar, albeit more subtle, cultural and ethnic connotation with Classical Arts, Sculptures, and Architectures from the Ancient Greek and Roman civilization.

Controversy

Among the opposition to the hanfu movement, a common concern is its implication for ethnic minorities. Skeptics fear that there is an element of exclusivity which could brew ethnic tensions, especially if it were to be nationalized.[27][28] For this reason, supporters of the movement are sometimes labeled as "Han chauvinists".[27]

Nevertheless, it has been insisted by some hanfu advocates that none of them have ever suggested that minorities must abandon their own indigenous styles of dress and that personal preference for a style of fashion can be independent of political or nationalistic motives.[27] Students consulted by Hua Mei cited the persistence of indigenous clothing among Chinese minorities, and the usage of kimono in Japan, hanbok in North Korea and South Korea, and traditional clothing used in India as an inspiration for the hanfu movement.[24] Even some ardent enthusiasts interviewed by the South China Morning Post in 2017, among them the Hanfu Society at Guangzhou University have cautioned against extending the dress beyond social normalization among Han Chinese people, acknowledging the negative repercussions politicization of the movement may have on society.[28]

According to Kevin Carrico, an lecturer at Monash University, there is a belief that the movement is inherently ethnic at its core, insists in that it is built on the narrative that the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty were dedicated to the destruction of the Han people, fundamentally transforming Chinese society. According to his research, conspiracy theories are made by some hanfu advocates which claim that a Manchu plot for restoration has been underway since the start of the post-1978 reform era, such that the Manchus control every important party-state institution.[29]

According to James Leibold, an associate professor in Chinese politics and Asian studies at La Trobe University, pioneers of the hanfu movement have confessed to believing that the issue of Han clothing cannot be separated from the larger issue of racial identity and political power in China. He cites the website Hanwang (Chinese: 漢網, 'Han Network') as an example of their Han supremacist agenda. Launched in 2003, Hanwang's constitution asserted that "Han culture is the world's most advanced and its race is one of the strongest and most prosperous" and endorsed the reintroduction of traditional Han clothing. Nonetheless, Leibold has mentioned that "one would be mistaken in believing that all Hanfu supporters share the political agenda embedded in the Hanwang constitution. Rather, the movement encompasses a very diverse group of individuals who find different sorts of meaning and enjoyment in the category of Han."[5][30]

Eric Fish, a freelance writer who lived in China from 2007 to 2014 as a teacher, student, and journalist, believed that the hanfu movement does have "patriotic undertones" but "most Hanfu enthusiasts are in it for the fashion and community more than a racial or xenophobic motivation". He also mentioned that contrary to popular belief, China's "young people overall are progressively getting less nationalistic".[31]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanfu movement. |

See also

Notes

- Ying, Zhi (2017). The Hanfu Movement and Intangible Cultural Heritage: considering The Past to Know the Future (MSc). University of Macau/Self-published. p. 12.

- Layton, Robert; Yifei, Luo (2019). Contemporary Anthropologies of the Arts in China. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-5275-2092-9. OCLC 1064685784.

- Zhao, Fujia (2018). "On the Educational Significance of Hanfu to Modern Society under the Background of Cultural Rejuvenation". International Journal of Social Science and Education Research. 1 (4): 74–80.

- Yeung, Juni L. (24 May 2016). "The Hanfu Revival Movement in Toronto". Torguqin. Toronto Guqin Society. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Leibold, James (September 2010). "More Than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet". The China Quarterly. 203: 539–559. doi:10.1017/S0305741010000585.

- Yangzom, Dicky (2014). Clothing and Social Movements: The Politics of Dressing in Colonized Tibet (MSc). City University of New York. p. 38.

- Chew, Matthew Ming-tak (January 2010). "Fashion and society in China in the 2000s: New developments and sociocultural complexities". ResearchGate. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- 呤唎 (February 1985). 《太平天國革命親歷記》. 上海古籍出版社.

- Godley, Michael R. (September 2011). "The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History". China Heritage Quarterly. China Heritage Project, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific (CAP), The Australian National University (27). ISSN 1833-8461.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1316453841.

- "北京"龙袍干尸"真容复原 解开男尸盘发髻谜团". Archived from the original on 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2014-01-28. Unknown parameter

|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "2021 latest updates on the Hanfu Movement". Newhanfu.

- "Han follow suit in cultural renaissance", Asian Times Online

- "Submission for a Proposal on hanfu dress for the 2008 Chinese Olympics to the China Olympics Committee" Archived 2007-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, Phoenix TV (in Chinese)

- 官方首次表态北京奥运礼服不用汉服 (in Chinese)

- 高, 春明 (1996). 《中國衣冠服飾大辭典》. 上海: 周汛. ISBN 7-5326-0252-4.

- 《宋史》:“吾家世為王民,自金人犯邊,吾兄弟不能以死報國,避難入關,今為曦所逐,吾不忍棄漢衣冠,願死於此,為趙氏鬼。”

- 倪在田 (1957). 《續明紀事本末》 (in Chinese). 臺灣大通書局. p. 214.

“(金)聲桓預作數十棺,全家漢服坐其中,自焚死。”

- 樊綽; 趙吕甫校释 (1985). 《云南志校释》 (in Chinese). 中国社会科学出版社. p. 143页.

“裳人,本漢人也。部落在鐵橋北,不知遷徙年月。初襲漢服,後稍参諸戎風俗,迄今但朝霞纏頭,其余無異。”

- 《馬關縣志·風俗志》.

“男子衣褲用棉布係以腰帶,有鈕扣與漢服略同者,稱之為漢苗”

- 《廣州市黃埔區志》.

“清末民初時期,大多數人都是以穿漢服(唐裝)為主”

- 羅, 雪揮 (2005-09-05). "《「漢服」先鋒》". 《中國新聞周刊》.

- ""汉服运动":互联网时代的种族性民族主义--《中国青年政治学院学报》2009年04期". 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2005-09-01.

- 华, 梅 (14 June 2007). "汉服堪当中国人的国服吗?". People's Daily Online.

- 週, 星 (2012). "漢服運動:中國互聯網時代的亞文化". ICCS Journal of Modern Chinese Studies. 4: 61–67.

- 周星 (2008). "新唐裝、漢服與漢服運動——二十一世紀初葉中國有關"民族服裝"的新動態". 《開放時代》 (3).

- "Should China Adopt Hanfu as Its National Costume? ", Beijing Review, 10 July 2007

- Yan, Alice (2018). "400 years after falling out of favour, the flowing, and sometimes controversial, robes of the Han ethnic group are back in style". South China Morning Post.

- Kevin Carrico, A State of Warring Styles

- Thomas Mullaney; Eric Armand Vanden Bussche; Stéphane Gros; James Patrick Leibold (2012). Critical Han Studies. Univ of California Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780520289758.

- Gaskin, Sam. "Fantasy, Not Nationalism, Drives Chinese Clothing Revival". The Business of Fashion. Retrieved 29 May 2019.