Hans Baldung

Hans Baldung (1484 or 1485 – September 1545), called Hans Baldung Grien,[lower-alpha 1] (being an early nickname, because of his predilection for the colour green), was an artist in painting and printmaking, engraver, draftsman, and stained glass artist, who was considered the most gifted student of Albrecht Dürer, whose art belongs to both German Renaissance and Mannerism. Throughout his lifetime, he developed a distinctive style, full of colour, expression and imagination. His talents were varied, and he produced a great and extensive variety of work including portraits, woodcuts, drawings, tapestries, altarpieces, stained glass, allegories and mythological motifs.

Hans Baldung | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait | |

| Born | Hans Baldung 1484 or 1485 Free Imperial City of Schwäbisch Gmünd |

| Died | September 1545 (aged c. 61) Free Imperial City of Strasbourg |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Albrecht Dürer |

| Known for | Printmaking, painting |

Baldung was born and raised in Schwäbisch Gmünd (Swabian Gmuend), East Wuerttemberg. At the age of 26, he married Margaretha Härlerin (née Herlin), with whom he had one child: Margarethe Baldungin.

Life

Early life, 1484–1500

Hans Baldung was the son of Johann Baldung, an university-educated jurist, having since 1492 the office of legal adviser to the bishop of Strasbourg (Albert of Bavaria), and Margarethe Herlin, daughter of Arbogast Herlin, he was not propertyless, but with unknown occupation,[2] and his family living in this city, Hans made his apprenticeship there, with an artist remained unknown. His exact date of birth is unknown. Hans was born in the small free city of Schwäbisch Gmünd (formerly Gmünd in Germany), a free city of the Empire, part of the East Württemberg region in former Swabia, Germany, in the year 1484 or 1485, into a family of intellectuals, academics and professionals, where his father was from and died in Strasbourg in September 1545.[3] His uncle, Hieronymus Baldung, was a doctor in medicine, he had a son, Pius Hieronymus, that can be seen as Hans' cousin, who taught law at Freiburg, and became by 1527 chancellor of the Tyrol.[2] In fact, Baldung was the first male in his family not to attend university, but was one of the first German artists to come from an academic family.[4] His earliest training as an artist began around 1500 in the Upper Rhineland by an artist from Strasbourg. He perfected his art in Albrecht Dürer's studio in Nuremberg between 1503 and 1507.[5][6]

At the age of 26, Baldung married Margaretha (née Herlin),[lower-alpha 2] with whom he had one child: Margarethe Baldungin.[7]

Life as a student of Dürer

Beginning in 1503, during the "Wanderjahre" ("Hiking years") required of artists of the time, Baldung became an assistant to Albrecht Dürer. Here, he may have been given his nickname "Grien". This name is thought to have come foremost from a preference to the color green: he seems to have worn green clothing. He probably also got this nickname to distinguish him from at least two other Hanses in Dürer's shop, Hans Schäufelein and Hans Suess von Kulmbach. He later included the name "Grien" in his monogram, and it has also been suggested that the name came from, or consciously echoed, "grienhals", a German word for witch—one of his signature themes. Hans quickly picked up Dürer's influence and style, and they became friends: Baldung seems to have managed Dürer's workshop during the latter's second sojourn in Venice. In a later trip to the Netherlands in 1521 Dürer's account book records that he took with him and sold prints by Baldung. On Dürer's death Baldung was sent a lock of his hair, which suggests a close friendship. Near the end of his Nuremberg years, Grien oversaw the production by Dürer of stained glass, woodcuts and engravings, and therefore developed an affinity for these media and for the Nuremberg master's handing of them.

Strasbourg

In 1509, when Baldung's time in Nuremberg was complete, he moved back to Strasbourg and became a citizen there. He became a celebrity of the town, and received many important commissions. The following year he married Margarethe Herlin, a local merchant's daughter,[8] joined the guild "Zur Steltz",[3] opened a workshop, and began signing his works with the HGB monogram that he used for the rest of his career. His style became much more deliberately individual—a tendency art historians used to term "mannerist." He stayed in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1513–1516 where he made, among other things, the High altar of the Freiburg Münster.[9]

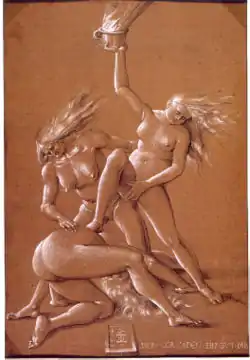

Witchcraft and religious imagery

In addition to traditional religious subjects, Baldung was concerned during these years with the profane theme of the imminence of death and with scenes of sorcery and witchcraft. He helped introduce supernatural and erotic themes into German art, although these were already amply present in Dürer's work. Most famously, he depicted witches, also a local interest: Strasbourg's humanists studied witchcraft and its bishop was charged with finding and prosecuting witches. His most characteristic works in this area are small in scale and mostly in the medium of drawing; these include a series of puzzling, often erotic allegories and mythological works executed in quill pen and ink and white body color on primed paper. The number of Hans Baldung's religious works diminished with the Protestant Reformation, which generally repudiated church art as either wasteful or idolatrous. But earlier, around the same time that he produced an important chiaroscuro woodcut of Adam and Eve, the artist became interested in themes related to death, the supernatural, witchcraft, sorcery, and the relation between the sexes. Baldung's fascination with witchcraft began early, with his first chiaroscuro print (1510) lasted to the end of his career.

Hans Baldung Grien's work depicting witches was produced in the first half of the 16th century, before witch hunting became a widespread cultural phenomenon in Europe. According to one view, Baldung's work did not represent widespread cultural beliefs at the time of creation but reflected largely individual choices.[10] On the other hand, through his family, Baldung stood as closer to the leading intellectuals of the day than any of his contemporaries, and could draw on a burgeoning literature on witchcraft, as well as on developing juridical and forensic strategies for witch-hunting. Baldung never worked directly with any Reformation leaders to spread religious ideals through his artwork, although living in fervently religious Strasbourg,[11] although he was a supporter of the movement, working on the high altar in the city of Münster, Germany.[12]

Baldung was the first artist to heavily incorporate witches and witchcraft into his artwork (his mentor Albrecht Dürer had sporadically included them but not as prominently as Baldung would). During his lifetime there were few witch trials, therefore, some believe Baldung's depictions of witchcraft to be based on folklore rather than the cultural beliefs of his time. By contrast, throughout the early sixteenth century, humanism became very popular, and within this movement, Latin literature was valorized, particularly poetry and satire, some of which included views on witches that could be combined with witch lore massively accumulated in works such as the Malleus Maleficarum. Baldung partook in this culture, producing not only many works depicting Strasbourg humanists and scenes from ancient art and literature, but what an earlier literature on the artist described as his satirical take on his depiction of witches. Gert von der Osten comments on this aspect of "Baldung [treating] his witches humorously, an attitude that reflects the dominant viewpoint of the humanists in Strasbourg at this time who viewed witchcraft as 'lustig,' a matter that was more amusing than serious".[10] However, the separation of a satirical tone from deadly serious vilifying intent proves difficult to maintain for Baldung as it is for many other artists, including his rough contemporary Hieronymus Bosch. Baldung's art simultaneously represents ideals presented in ancient Greek and Roman poetry, such as the pre-16th century notion that witches could control the weather, which Baldung is believed to have alluded to in his 1523 oil painting "Weather Witches", which showcases two attractive and naked witches in front of a stormy sky.[10]

Baldung also regularly incorporated scenes of witches flying in his art, a characteristic that had been contested centuries before his artwork came into being. Flying was inherently attributed to witches by those who believed in the myth of the Sabbath (without their ability to fly, the myth fragmented), such as Baldung, which he depicted in works like "Witches Preparing for the Sabbath Flight" (1514).[13]

Work

Painting

.jpg.webp)

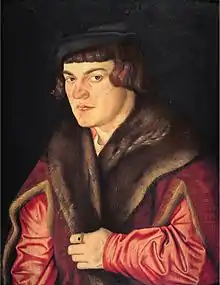

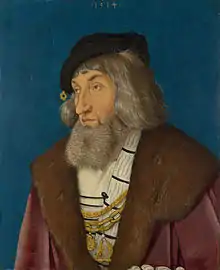

Throughout his life, Baldung painted numerous portraits, known for their sharp characterizations. While Dürer rigorously details his models, Baldung's style differs by focusing more on the personality of the represented character, an abstract conception of the model's state of mind. Baldung settled eventually in Strasbourg and then to Freiburg im Breisgau, where he executed what is held to be his masterpiece.[14] Here in painted an eleven-panel altarpiece for the Freiburg Cathedral, still intact today, depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin, including, The Annunciation, The Visitation, The Nativity, The Flight into Egypt, The Crucifixion, Four Saints and The Donators. These depictions were a large part of the artist's greater body of work containing several renowned pieces of the Virgin.[15]

The earliest pictures assigned to him by some are altar-pieces with the monogram H. B. interlaced, and the date of 1496, in the monastery chapel of Lichtenthal near Baden-Baden. Another early work is a portrait of the emperor Maximilian, drawn in 1501 on a leaf of a sketch-book now in the print-room at Karlsruhe. "The Martyrdom of St Sebastian and the Epiphany" (now Berlin, 1507), were painted for the market-church of Halle in Saxony.[16]

Baldung's prints, though Düreresque, are very individual in style, and often in subject. They show little direct Italian influence. His paintings are less important than his prints. He worked mainly in woodcut, although he made six engravings, one very fine. He joined in the fashion for chiaroscuro woodcuts, adding a tone block to a woodcut of 1510. Most of his hundreds of woodcuts were commissioned for books, as was usual at the time; his "single-leaf" woodcuts (i.e. prints not for book illustration) are fewer than 100, though no two catalogues agree as to the exact number.

Unconventional as a draughtsman, his treatment of human form is often exaggerated and eccentric (hence his linkage, in the art historical literature, with European Mannerism), whilst his ornamental style—profuse, eclectic, and akin to the self-consciously "German" strain of contemporary limewood sculptors—is equally distinctive. Though Baldung has been commonly called the Correggio of the north, his compositions are a curious medley of glaring and heterogeneous colours, in which pure black is contrasted with pale yellow, dirty grey, impure red and glowing green. Flesh is a mere glaze under which the features are indicated by lines.[16]

His works are notable for their individualistic departure from the Renaissance composure of his model, Dürer, for the wild and fantastic strength that some of them display, and for their remarkable themes. In the field of painting, his Eve, the Serpent and Death (National Gallery of Canada) shows his strengths well. There is special force in the "Death and the Maiden" panel of 1517 (Basel), in the "Weather Witches" (Frankfurt), in the monumental panels of "Adam" and "Eve" (Madrid), and in his many powerful portraits. Baldung's most sustained effort is the altarpiece of Freiburg, where the Coronation of the Virgin, and the Twelve Apostles, the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity and Flight into Egypt, and the Crucifixion, with portraits of donors, are executed with some of that fanciful power that Martin Schongauer bequeathed to the Swabian school.[16]

He is well known as a portrait painter, his works include historical pictures and portraits; among the latter may be named those of Maximilian I. and Charles V.[14] His bust of Margrave Philip in the Munich Gallery tells us that he was connected with the reigning family of Baden as early as 1514. At a later period he had sittings with Margrave Christopher of Baden, Ottilia his wife, and all their children, and the picture containing these portraits is still in the gallery at Karlsruhe. Like Dürer and Cranach, Baldung supported the Protestant Reformation. He was present at the diet of Augsburg in 1518, and one of his woodcuts represents Luther in quasi-saintly guise, under the protection of (or being inspired by) the Holy Spirit, which hovers over him in the shape of a dove.[16]

Selected works

_-_WGA01206.jpg.webp)

- Phyllis and Aristotle, Paris, Louvre. 1503

- Two altar wings (Charles the Great, St. George), Augsburg, State Gallery.

- Portrait of a Youth, Hampton Court, Royal Collection 1509

- The birth of Christ, Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel, 1510

- The Adoration of the Magi, Dessau, Anhalt Art Gallery, 1510

- The Witches, 1510

- The Mass of St. Gregory, Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1511

- The crucifixion of Christ, Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel, 1512

- The crucifixion of Christ, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, 1512

- The Holy Trinity, London, National Gallery, 1512

- The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Vienna, Paintings Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts , 1513

- Portrait of a Man, London, National Gallery, 1514

- The Lamentation of Christ, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, 1516

- Death and the Maiden, Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel, 1517

- The Baptism of Christ, Frankfurt am Main, Städel, 1518

- Venus with Cupid, Otterlo, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, 1525

- Pyramus and Thisbe, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, around 1530

- Ambrosius Volmar Keller, Strasbourg, Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, 1538

- Christ as a Gardener, Darmstadt, Hessen State Museum, 1539

- Adam and Eve, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi - Uffizi

- The unlikely couple, Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, 1527

- The Three Ages of Man and Death, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Mercury as a Planet God, Stockholm, National Museum, 1530–1540

- Harmony, or The Three Graces Die Jugend (Die drei Grazien) The youth (the three graces) Museo del Prado between 1541 and 1544

- Selected works

The Virgin as Queen of Heaven with the Christ Child in her arms

The Virgin as Queen of Heaven with the Christ Child in her arms Mater Dolorosa

Mater Dolorosa Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Rest on the Flight into Egypt Nativity

Nativity Adam

Adam Eve

Eve Lucretia. Drawing with bodycolor

Lucretia. Drawing with bodycolor John of Patmos Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1510

John of Patmos Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 1510

The Mass of St Gregory, 1511

The Mass of St Gregory, 1511 Woodcut of Phyllis and Aristotle, 1515

Woodcut of Phyllis and Aristotle, 1515 The Lamentation of Christ, 1516

The Lamentation of Christ, 1516 Beheading of St Dorothea, 1516

Beheading of St Dorothea, 1516 Death and the Maiden, 1517

Death and the Maiden, 1517 Venus with Cupid, 1525

Venus with Cupid, 1525_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18076.tif.jpg.webp) Mercury , 1530–1540

Mercury , 1530–1540 Harmony, 1541

Harmony, 1541 Madonna in the Vine Arbour, 1541–1543

Madonna in the Vine Arbour, 1541–1543

Notes

- Diversely spelled Hans Baldung or Hans Baldung Grien in biographical dictionaries of the nineteenth century, the spelling of his name, now attested by the artist's signature, is now followed by the painter's main biographers.[1]

- In a manuscript, known as the 'Collectanea genealogica', she is quoted as 'Margred Härlerin'.[7]

References

Citations

- Baynes & Smith 1880, p. 224.

- Brady 1975, p. 304.

- Brady 1975, p. 298.

- Brady 1975, pp. 303-304.

- Kelleher & Bott 1986, p. 363.

- Térey 1894, pp. 33-34.

- von Pettenegg 1877, p. 2.

- Brady 1975, p. 305.

- Hagen 2001, pp. 18–27.

- Sullivan 2000, pp. 333–401.

- Rowlands 1981, p. 263.

- Nenonen & Toivo 2013, p. 56.

- Hults 1987, pp. 249–276.

- Thomas 1870, p. 251.

- Cleef 1907.

- Ashby 1911, p. 640.

- Baynes, T. S.; Smith, W.R., eds. (1880). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 224.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cleef, Augustus Van (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brady, Thomas A. (1975). "The Social Place of a German Renaissance Artist: Hans Baldung Grien (1484/85-1545) at Strasbourg". Central European History. 8 (4): 295–315. doi:10.1017/S0008938900017994. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 4545752.

- Hults, Linda C. (1987). "Baldung and the Witches of Freiburg: The Evidence of Images". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 18 (2): 249–276. doi:10.2307/204283. ISSN 0022-1953. JSTOR 204283.

- Rowlands, John (1981). "Washington and Yale. Hans Baldung Grien". The Burlington Magazine. 123 (937): 263. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 880364.

- Sullivan, Margaret A. (2000). "The Witches of Dürer and Hans Baldung Grien". Renaissance Quarterly. 53 (2): 333–401. doi:10.2307/2901872. ISSN 0034-4338. JSTOR 2901872.

- Térey, Gábor (1894). "Verzeichniss der Gemälde des Hans Baldung Gen. Grien Zusammengestellt" [List of paintings by Hans Baldung called Grien compiled]. 1st. Strasbourg: J.H.E. Heitz. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - von Pettenegg, Eduard Gaston Pöttickh (1877). "Neues Jahrbuch - Heraldisch-Genealogische Gesellschaft "Adler"" [New year book of the Heraldic-Genealogical Society "Eagle"] (in German). 4th. Graz: Heraldic-Genealogical Society "Adler". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ashby, Thomas (1911). "Grün". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 329–640.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ashby, Thomas (1911). "Grün". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 329–640.

Bibliography

- Bartrum, Giulia (1995). German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2604-3.

- Koerner, Joseph (1993). The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-44999-9.

- Bach, Sibylle Weber am (2006). Hans Baldung Grien (1484/85-1545). Marienbilder in der Reformation [Hans Baldung Grien (1484/85-1545). Images of Mary in the Reformation]. Studien zur christlichen Kunst (in German). 6. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner.

- Hagen, Rainer (2001). La peinture du XVIe siècle [16th century painting] (in French). Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5559-6.

- Kelleher, Bradford D.; Bott, Gerhard (1986). O'Neill, John P.; Ellen, Shultz (eds.). Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg, 1300-1550. Translated by Stockman, Russell M. Munich: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-466-1.

- Meyer, Julius (1878). Allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon [General artist lexicon] (in German). 2nd. Vol. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

- Nagler, Georg Kaspar (1863). Die Monogrammisten und diejenigen bekannten und unbekannten Künstler aller Schulen [The monogrammists and those known and unknown artists of all schools.] (in German). 3rd. Vol. Munich: Georg Franz.

- Nenonen, Marko; Toivo, Raisa Maria (2013). Writing witch-hunt histories: Challenging the Paradigm. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25791-7.

- Thomas, Joseph (1870). Universal Pronouncing Dictionary of Biography and Mythology. 1st Vol. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hans Baldung. |

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Hans Baldung (see index)

- Article: Sacred and Profane: Christian Imagery and Witchcraft in Prints by Hans Baldung Grien, by Stan Parchin

- "Hans Baldung Grien", National Gallery of Art

- Hans Baldung in the "A World History of Art"

- Several of Baldung's witches and erotic prints