Hark, Hark! The Dogs Do Bark

"Hark, Hark! The Dogs Do Bark" is an English nursery rhyme. Its origins are uncertain and researchers have attributed it to various dates ranging from the late 1000s to the early 1700s. The earliest known printings of the rhyme are from the late 1700s, but a related rhyme was written down a century earlier than that.

.jpg.webp)

Historians of nursery rhymes disagree as to whether the lyrics of "Hark Hark" were inspired by a particular episode in English history, as opposed to simply reflecting a general and timeless concern about strangers. Those who link the rhyme to a specific episode identify either the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the 1530s, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 or the Jacobite rising of 1715. Those who date it to the Tudor period of English history (i.e., the 1500s) sometimes look to the rhyme's use of the word jag, which was a Tudor-period word for a fashionable style of clothing. But other historians ascribe no particular relevance to the use of that word.

Informal references to the nursery rhyme attribute the reason to the various enclosures acts whereby large landowners could appropriate smaller holdings merely by fencing them in.

"Hark Hark" survives to this day largely as a nursery rhyme. It has been sufficiently well-known to permit writers to invoke it, sometimes in parodied form, in material not intended for children. This includes parodies by literary authors such as James Thurber and D. H. Lawrence. A few prose stories have used the rhyme as their source, including one by L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

The rhyme appears in the Roud Folk Song Index as entry 19,689.[1]

Lyrics

As commonly published in the early 1800s, the rhyme was:[2]

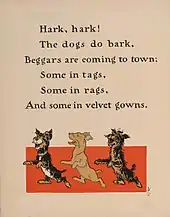

Hark, hark! the dogs do bark,

Beggars are coming to town.

Some in rags, some in jags,

And some in velvet gowns.

Various published versions incorporate minor grammatical variations. More noticeably, many versions exchange the order of rags and jags; some replace the word jags with tags. A few versions specify that there is only one person wearing a velvet gown; at least one says that the gown material is silken, not velvet.[3]

No particular ordering of rags and jags was dominant in the 19th-century sources. And although the use of tags was less common, it did appear in some of the early 19th-century publications. In Britain, it is found as early as 1832 in an article in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.[4] Even earlier than that, in 1824, it was used in an American book, The Only True Mother Goose Melodies.[5]

Some sources give the rhyme a second verse, whose first two lines are "Some gave them white bread / Some gave them brown".[6] It is unclear why they associate the lines with "Hark Hark", because most sources give them as part of "The Lion and the Unicorn" (a nursery rhyme that is also included in the Roud Folk Song Index, as entry 20,170).[7]

Initial publications

The first publication of the rhyme appears to be the 1788 edition of Tommy Thumb's Song Book. As reported by the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, the rhyme was included in that text under the title "Hark Hark".[8] It is not known whether it was included in any earlier edition of the Song Book (whose first edition was in 1744). The rhyme saw at least one other pre-1800 publication—the 1794 first edition of Gammer Gurton's Garland. The evidence for this is indirect. It appears in the 1810 second edition of Gammer Gurton's, the Preface of which states that Parts I and II of the book were "first collected and printed by a literary gentleman deceased", but that Parts III and IV "are now first added". "Hark Hark" appears in Part II.[9] The rhyme's appearance in the 1794 edition is corroborated by the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.[10]

Origins

The origins of "Hark Hark" are uncertain. Various histories of nursery rhymes have offered competing theories on the matter, as have authors who write about other aspects of English history.

One modern history, by Albert Jack, offers two theories of the rhyme's origin, each one dating it to a specific episode in English history. The first theory places it during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. According to the theory, the Dissolution would have caused many people (not just the monks, but others who were economically dependent on the monasteries) to become homeless and to wander through towns seeking assistance. The other theory dates the rhyme to the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which the Dutch William of Orange took the English throne. In support of this theory, Jack notes that the word "beggar" might have been seen as a play on the name "Beghard", a Dutch mendicant order widespread in Western Europe in the 13th century.[11] Another modern history (by Karen Dolby) presents similar theories. It cites the Glorious Revolution and also admits a possible origin in the Tudor period, though without specifying the Dissolution as the precipitating episode.[12]

An oft-quoted 19th-century compilation of English nursery rhymes, that of James Halliwell-Phillipps, does not offer any theory as to the rhyme's origins. But it classifies "Hark Hark" as a "Relic", even though it classifies others as "Historical".[13]

.jpg.webp)

Dating the rhyme's origin is confounded by the existence of another that shares the same first line and overall structure. A lyric appearing in a hand-written text from 1672, also titled "Hark, Hark, the Dogs Do Bark", is not a nursery rhyme and does not address beggars. Instead, its first verse reads:[14]

Hark, hark! the dogs do bark,

My wife is coming in,

With rogues and jades and roaring blades,

They make a devilish din.

When discussing a different song in his English Minstrelsie (1895), Sabine Baring-Gould touches upon the 1672 lyric and notes its similarity with the nursery rhyme. However, he states that the nursery rhyme is the later of the two, describing it as a "Jacobite jingle" that arose in the years after the House of Hanover gained the English throne in 1714. But Baring-Gould also notes the similarity of the opening line to one used by Shakespeare in The Tempest—"Hark, hark! the watchdogs bark!". The Tempest is believed to have been written at about 1610.[15]

Right: Detail from a portrait of Henry VIII (1530s), showing numerous small jags cut into the body and sleeves of his doublet, through which "puffs" of the underlying shirt have been pulled through.

The precise meaning of jags might also play a role in dating the rhyme's origins. In the mid 1800s, English provincial dictionaries did not recognize it as a word for any type of garment. But they did recognize the phrase rags and jags, which was understood to mean remnants or shreds of clothing.[16] However, the word had a different clothing-related meaning in earlier centuries. In the 1400s, the word was used to describe a fashion, first popular in Burgundy, of slitting or otherwise ornamenting the borders or hems of a garment.[17] Over time, the word's meaning changed to describe the newer fashion of cutting slashes into the fabric of a garment to reveal the material being worn underneath.[18] With this latter meaning, jags entered the vocabulary of Tudor-era writers. In one of his contributions to the Holinshed's Chronicles (1577), William Harrison used the word to describe current fashions in England—"What should I say of their doublets ... full of jags and cuts".[19] The word was used in the 1594 version of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew, where one character says to a tailor "What, with cuts and jags? ... Thou hast spoil'd the gowne."[20] And in the early 1700s, the anonymous translator of a 1607 book by an Italian writer also used jags in a specific clothing-related sense, linking it to garments made of velvet.[21]

But even amongst historians who date the rhyme to Tudor England, the extent to which their conclusions are based on the Tudor-era meaning of jags is not clear. Historian Reginald James White unequivocally dates it to this period, but does not give a reason and, instead, uses the rhyme as part of his discussion of economic conditions in 16th-century England.[22] Shakespeare historian Thornton Macauley also is certain that the rhyme dates back to this period, but bases that finding on his belief that the "beggars" were understood to be travelling actors.[23] Closer to using the word to date the rhyme to the Tudor period is Linda Alchin's The Secret History of Nursery Rhymes. In her text, Alchin defines the word jags and explicitly links it to Tudor-period fashion. But she does not go so far as to say that the use of the word itself dates the rhyme to that period.[24][25]

In his 2004 history of nursery rhymes, Chris Roberts discusses several of the varying theories on the origins of "Hark Hark". But he also opines that the rhyme has "a fairly universal theme" that "could be used to describe any time from the Middle Ages to the present day".[26]

In the 1830s, John Bellenden Ker noted that many English sayings and rhymes seem to be gibberish or nonsensical (e.g., "Hickory Dickory Dock"), but proposed that this was the case only because their original meanings have been forgotten. Ker believed those sayings and rhymes to be mis-rememberings of ones that were developed by the native English population in the decades following the Norman conquest in 1066. The rhymes, said Ker, would have been made in the Old English language, but their original meanings could be recovered if the modern words were understood to be sound-alike substitutions for the original. Ker also proposed that the closest known equivalent to Old English was the 16th century version of the Dutch language, and that looking for sound-alike Dutch words would be sufficient for recovering the Old English meanings.[27]

Ker wrote several books exploring this theory, increasingly applying it to rhymes that were not gibberish or nonsensical. "Hark Hark" was addressed in the last of them. When analyzing it, Ker concluded that the word "bark" was a mis-remembering of bije harcke, which he translated as "harasser of the bee" and then assumed "bee" to have been a metaphor that the Anglo-Saxon population used for itself. He also found the word "town" to be a mis-remembering of touwe, meaning "rope", which he assumed to be a metaphor for a hangman's noose. With these and several other similar inferences, Ker found the original meaning of "Hark Hark" to be that of political protest against the Norman government and the Catholic Church (a conclusion he reached with most of the rhymes that he studied).[2] Ker's theory was not well-accepted. In a contemporaneous discussion of it, The Spectator found the theory to be a "delusion" and "the clearest case of literary mania we remember".[28] His writings were still being discussed several decades later, and still not favorably. Grace Rhys called Ker's theory "ingenious if somewhat addlepated".[29] And in the Preface of a facsimile reprint of The Original Mother Goose's Melody, William Henry Whitmore noted Ker's work and added that "opinions differ as to whether he was simply insane on the subject, or was perpetrating an elaborate joke".[30]

Popular usage

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark.

For Eben is coming to town.

His money in bags, his children in rags,

And his wife in a velvet gown.

— Excerpt from a 1921 serialized novel[31]

.jpg.webp)

In both England and the United States, the rhyme became so familiar that authors often alluded to it, either in its entirety or to just its first line.

Quoting the entire rhyme, but modifying a few of the words, was sometimes done as a way of making a point. This is how it was used by an anonymous contributor to Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, who was commenting on the general character of the Members of Parliament expected to be elected as a result of the soon-to-be enacted Reform Acts of 1832. The contributor wrote that "it will be a strange sight to see the new delegates entering the metropolis, and will perchance remind you of your old nursery rhymes". This was followed with the lyrics to "Hark Hark", but with the line "some in velvet gown" changed to "none in velvet gown" [italics in original]).[4] An 1888 example from the United States sees a similar thing being done in the caption of a political cartoon. The cartoon lampoons Grover Cleveland's position on tariffs and changes the names of the garments to "Italian rags", "German tags" and "English gowns".[32]

Even without modification, the rhyme has served either to illustrate or to emphasize some point being made by the writer. In an 1835 article in Blackwood's, an unidentified contributor linked nursery rhymes to various political issues, using "Hark Hark" in specific reference to the Reform Acts passed in Britain earlier that decade.[33] And the rhyme was used by Theodore W. Noyes in his 1900 journalistic correspondence to the Washington Evening Star to convey his impressions of the Sultan of Sulu's retinue, who were meeting with an American diplomatic delegation.[34]

It has also been used as an epigraph to some larger piece of work. In the 1850s, poet Adeline Dutton Train Whitney used "Hark Hark" to introduce one of her works in Mother Goose for Grown Folks.[35] More recent years have seen the rhyme being used in similar fashion, but not in literary works. Instead, it has appeared a few times as epigraphs to particular chapters in scholarly non-literary texts, including one written by Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto Polar[36] and another by South African journalist Allister Sparks.[37]

The first line of the rhyme entered the official transcript of the New Zealand House of Representatives in 1953. In September of that year, Eruera Tirikatene was asking a series of questions regarding Māori affairs. At one point, Geoffrey Sim responded to Tirikatene's comments by exclaiming "Hark, hark, the dogs do bark! It is difficult to get a word in," to which Tirikatene responded "You are like a dog barking at the moon." Speaker of the House Matthew Oram immediately re-established order.[38]

In Men At Arms, a novel by Terry Pratchett, "Hark, Hark" is said to be a part of the Charter of the Beggars Guild.

Adaptations

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark.

But only one in three.

They bark at those in velvet gowns,

But never bark at me.

The Duke is fond of velvet gowns,

He'll ask you all to tea.

But I'm in rags, and I'm in tags,

He'll never send for me.

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The Duke is fond of kittens.

He likes to take their insides out,

And use their fur for mittens.

— from The 13 Clocks (1950)[39]

When the Communist Party of Italy was formed in early 1921, writer D.H. Lawrence was living in Sicily and wrote a poem expressing his opinions of the group.[40] The poem, "Hibiscus and Salvia Flowers", starts with a parody of "Hark Hark", reading:

Hark! Hark!

The dogs do bark!

It's the socialists come to town,

None in rags and none in tags,

Swaggering up and down.

Elements of the rhyme recur at various points in the poem. It receives extended critical analysis in Allan Rodway's The Craft of Criticism.[41]

James Thurber's 1950 fantasy novel The 13 Clocks has a prince deliberately trying to get arrested by the evil Duke of Coffin Castle, who has imprisoned a beautiful princess. The prince does this by disguising himself as a wandering minstrel and singing a song whose verses are increasingly critical of the duke. Each verse is a re-working of "Hark Hark".

The rhyme has been used at least twice as the basis for a longer work of prose. Mary Senior Clark used it for a two-part story that appeared in the November and December 1868 issues of Aunt Judy's Magazine, as part of its "Lost Legends of the Nursery Songs" series.[42] And L. Frank Baum (author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) used it for his 1897 story "How the Beggars Came to Town". The story appeared in his Mother Goose in Prose and had illustrations by Maxfield Parrish.[43] Both Clark and Baum used the rhyme as an epigraph to the story.

An anonymous author writing in 1872 for Scribner's Monthly used each of the rhyme's lines as the headings of separate sections of a much longer poem, "The Beggars". Each section of the poem was an expansion of the line quoted in the heading.[44] An 1881 publication saw Mary Wilkins Freeman using the rhyme as the basis for a 50-verse poem about the "beggar king" of an army, his daughter and the emperor. Freeman re-used the traditional lines at various portions of the poem.[45]

A parodied two-verse version is recited in the 1977 film The Prince and the Pauper, even though it does not appear in the original novel by Mark Twain.[46]

Musical recordings

The rhyme has appeared on many recordings intended for children (and see the External links section below for a partial listing of such recordings). The earliest known recording appears to be the one done by Lewis Black in the 1920s for the Victor Talking Machine Company. It was part of an "album" of eight 78 rpm discs, collectively titled Songs for Little People. "Hark Hark" is in a medley on the album's third disc (Victor, 216527-A).[47]

Recordings by other notable artists include:

- Derek McCulloch, as Uncle Mac – Nursery Rhymes (No. 4) (His Master's Voice, 7EG 8487). This is a 7-inch extended play record. The year of issue is not known, but McCulloch died in 1967.

- Mike Sammes, as The Michael Sammes Singers – Nursery Rhyme Toys (HMV Junior, 7EG 108). This is a 7-inch extended play record issued in 1959.

- Wally Whyton – A Treasury of 250 Favourite Children's Songs (Readers Digest (UK), GFCS 6A-S2). This is a 6-LP box set issued in 1976. "Hark Hark" appears on the second LP.

- Unknown, but attributed to Rupert the Bear – Rupert Sings a Golden Hour of Nursery Rhymes (Golden Hour (Pye Records), GH 546). This is an LP issued in 1972.

A rock version not intended for children was recorded by Terry Edwards and the Scapegoats in 2008 (Orchestral Pit, OP4). It appears on a 7-inch single as the B-side to "Three Blind Mice". Most of the recording does not feature vocals; the rhyme appears mid-way through the recording.

References

- "RN19689". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- Ker, John Bellenden (1840). Essay on the Archæology of Our Popular Phrases, Terms and Nursery Rhymes. Volume 1. Andover (England): printed by John King. pp. 299–300.

- The phrase "silken gown" appears in the rhyme published in Baker, Anne Elizabeth (1854). Glossary of Northamptonshire Words and Phrases (Vol. II ed.). London: John Russell Smith. p. 155. The rhyme appears as a colloquial example of the phrase "Rags and Jags".

- Anonymous (attributed to Satan) (April 1832). "The Art of Government Made Easy". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. Vol. 31 no. 192. pp. 665–672. The rhyme, in slightly parodied form, appears on page 671.

- The Only True Mother Goose Melodies. Boston: J.S. Locke. 1870 [1833]. p. 26. No author or editor is identified. The linked version is a facsimile of the original 1833 printing by Munroe & Francis of Boston. Historian William Henry Whitmore reports that this 1833 printing was a re-publication of most of the material that appeared in Munroe & Francis's 1824 Mother Goose's Quarto: or, Melodies Complete. "Hark Hark" appeared in the 1824 printing at page 22 and was accompanied by a woodcut illustration by Nathaniel Dearborn. See Whitmore, William H., ed. (1892). The Original Mother Goose's Melody. Boston: Damrell & Epham. pp. 19–29. The detail on "Hark Hark" appears on page 23.

- "Hark! Hark1 The Dogs Do Bark". mamalisa.com. Lisa Yannucci. Retrieved 19 December 2017. A 19th-century example, with an illustration by Kate Greenaway, is Mother Goose, or the Old Nursery Rhymes. London: Frederick Warne. 1881. p. 9. ISBN 9781582180465.

- See The Only True Mother Goose Melodies. Boston: J.S. Locke. 1870 [1833]. p. 28. Also see Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1899) [1895]. The Heart of Oak Books: First Book: Rhymes and Jingles. Boston: D.C. Heath. p. 41.

- "Hark Hark". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society. Retrieved 10 December 2017. Note that the rhyme does not appear in an 1814 reprint done in Scotland. See Lovechild, Nurse (1814). Tommy Thumb's Song Book: For All Little Masters and Misses. Glasgow: J. Lumsden.

- R. Triphook, ed. (1810). Gammer Gurton's Garland: or, The Nursery Parnassus. London: Harding and Wright. p. 26.

- "Hark, Hark, the Dogs Do Bark". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society. Retrieved 10 December 2017. The Library places the rhyme at page 60 of the first edition.

- Jack, Albert (2009). Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes. Perigee. n.p. ISBN 978-1-101-16296-5. LCCN 2009025233. The connection between "beggar" and "Beghard" is corroborated by the Oxford English Dictionary, which states that the word is indeed derived from the name of the Dutch mendicant order. See Murray, James A. H., ed. (1877). "Beg". A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles. 1 (part 2). Oxford (England): Clarendon Press. p. 765 (bottom of middle column). But it is contradicted by a different etymology, which traces beg to the Old English word for bag. See Donald, James, ed. (1875). "Beg". Chambers's Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. London: W. and R. Chambers. pp. 36, 30.

- Dolby, Karen (2012). "There Was an Old Woman: Once Upon a Time". Oranges and Lemons: Rhymes from Past Times. London: Michael O'Mara Books. n.p. ISBN 978-1-84317-975-7.

- Halliwell, James Orchard, ed. (1853). Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Tales of England (5th ed.). London: Frederick Warne. p. 120. Halliwell-Phillips does not state what caused him to classify a rhyme either as a "Relic" or as "Historical". But the Historical section is restricted to rhymes that either contain explicit reference to known historical personages, or for which Halliwell-Phillips added a discussion of the rhyme's historical context. The "Historical" rhymes are given at pages 1–6.

- "Hark, hark! The Dogs do bark! [B]". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society. Retrieved 18 January 2018. The item is number SBG/1/2/731 of the Sabine Baring-Gould Manuscript Collection.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine, ed. (1895). English Minstrelsie: A National Monument of English Song, Volume 2. Edinburgh: Grange Publishing Works. p. xvi. The line comes from Ariel's Song in Act 1, Scene II. For the dating of The Tempest, see Orgel, Stephen (1987). The Tempest. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-19-953590-3.

- Holloway, William (1840). "Rags and Jags". A General Dictionary of Provincialisms. London: John Russell Smith. p. 137. Also see Brewer, E. Cobham (1882). ""Rags and Jags"". Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (14th ed.). London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin. p. 733. Note that the Holloway dictionary does recognize jag as a word, but not one that relates to clothing (see page 89). On the other hand, one dictionary corroborates the general meaning of rags and jags, but also states that jags could be used by itself to signify a tattered garment. See Wright, Joseph, ed. (1902). "Jag". The English Dialect Dictionary. III: H–L. London: Henry Frowde (for the English Dialect Society). p. 343 (middle of second column). And the Scottish dialect used the word to mean calf leather, but also to mean things made from that leather, including boots. See page 342 of the Wright dictionary (middle of the second column), as well as Jamieson, John; Johnstone, John; Longmuir, John, eds. (1867). "Jag". Jamieson's Dictionary of the Scottish Language (New, Revised and Enlarged ed.). Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo. p. 288.

- Bruhn, Wolfgang; Tilke, Max (1988) [1955]. "Burgundian Fashion: 1425–90". A Pictorial History of Fashion. New York: Arch Cape Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-517-65832-1. LCCN 87-35084. Also see Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, C. W.; Cunnington, P. E. (2010). "Dag, dagges, dagging, jags, jagging". The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg Publishers. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-84788-534-0.

The term applied to the slashing of any border of a garment into tongues, scalops, leaves or vandykes, called "dagges", as a form of decoration.

The entry also notes that this meaning of jags was in use only until the late 1400s. - Hayward, Maria (2016) [2009]. "Glossary: Jag". Rich Apparel: Clothing and the Law in Henry VIII's England. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-4096-7. LCCN 2008-37955.

Jag: a dag or pendant made by cutting the edge of a garment; also a slash or cut in the surface of a garment to reveal a different color beneath

And see page 29 of Bruhn, Wolfgang; Tilke, Max (1988) [1955]. "Burgundian Fashion: 1425–90". A Pictorial History of Fashion. New York: Arch Cape Press. ISBN 978-0-517-65832-1. LCCN 87-35084, where the authors use the word jags to describe what would now be called buttonholes. - Harrison, William (1587) [1577]. "Of Their Apparel and Attire". A Description of Elizabethan England. pp. 171–172. The quoted phrase appears in the second column of page 172, at lines 18–20. Harrison uses the word again at line 58. The Harrison material was re-printed in a more legible, but slightly abridged, form in Anonymous (attributed to "A Lady of Rank") (1847). The Book of Costume, or Annals of Fashion, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (New ed.). London: Henry Colburn. pp. 103–106. The relevant passages are on page 105 of the text. Although published anonymously, the HathiTrust believes the author to be Mary Margaret Stanley Egerton, Countess of Wilton and wife of Thomas Egerton, 2nd Earl of Wilton.

- Act III, Scene V, line 18, as seen in Boas, F. S., ed. (1908). The Taming of a Shrew: Being the Original of Shakespeare's 'The Taming of the Shrew'. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 43. Note that Boas does not believe that Shakespeare actually wrote the line. See his discussion of authorship at pages xxxii–xxxvii of the book's Introduction.

- Pancirollus, Guido (1715) [1607]. "Of Woven Silks, or Silken Webs". The History of Many Memorable Things Lost. London: John Nicholson. p. 403.

Lampridius tells us, that Alexander Severus never wore any garment of velvet, which we now see daily tatter'd into jags, even by the meaner sort.

Note that jags is the English word chosen by the translator (possibly Nicholson). In the original 1607 publication, Pancirollus wrote in Latin and used the word lacerari (see page 729 of the original 1607 publication). - White, R.J. (1967). A Short History of England. Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-521-09439-9. LCCN 67-11531.

For Tudor England lived in terror of the tramp, and it is to this time that we can trace back the nursery rhyme ... .

- Macauley, Thornton (April 1897). "Shakespearean Actors of Two Centuries". The American Shakespeare Magazine. Vol. 3. New York. pp. 112–115.

An inkling of the common opinion of [actors] has come down to us in the following nursery rhyme, written of their swarming from the country into London in the dramatic season ... .

The quote is taken from page 113. - Alchin, Linda (2013) [2004]. The Secret History of Nursery Rhymes. Mitcham (England): Neilsen. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-9567486-1-4. OCLC 850182236. In the version that appears on her www.rhymes.org.uk website, Alchin states that "Hark Hark" dates back to the 13th century. It is not clear which of the two versions (print or website) is the earlier. Dating the rhyme to the 13th century also is done by Boileau, Nicolas Pierre (15 June 2007). "'Hark, hark, the dogs do bark': Is Children's Poetry Threatening Janet Frame in An Autobiography?". E-rea. 5 (1). doi:10.4000/erea.188 – via OpenEdition. Boileau's article discusses the influence of rhymes (including "Hark Hark") on the work of author Janet Frame. Both Alchin and Boileau give their 13th-century datings along with linking the word jags to the Tudor era.

- A different opinion as to the meaning of jags is given by the editor of a reprint of Virginia Woolf's The Waves. That editor dates the rhyme to the 1500s but states that the phrase in jags means "on the spree". See Bradshaw, David, ed. (2015) [1931]. The Waves. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-19-964292-2. LCCN 2014935579. But Bradshaw appears to be conflating the then-modern meaning of jags with its Tudor-era meaning. For the word's usage in early 20th-century America, see Johnson, Trench H. (1906). Phrases and Names: Their Origins and Meanings. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. p. 166.

Jag. An Americanism for drunkenness. ...

- Roberts, Chris (2006). "Who Let Them Out?: Hark, hark, the dogs do bark". Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme (2nd ed.). New York: Gotham Books. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-1-592-40130-7. LCCN 2004-27431.

- Ker, John Bellenden (1834). "Preface". An Essay on the Archaiology of Popular English Phrases and Nursery Rhymes. Southampton: Fletcher and Son. The theory is set forth at pages v–viii. Ker discusses it again, with specific respect to nursery rhymes, later in the text (at pages 121–122). In the latter discussion, Ker opines that the mis-rememberings happened at a time when the Old English language was changing and also notes that it happened at a time when a "foreign and onerous church-sway" had already taken hold. It is known that Old English underwent such a change in the aftermath of the Norman conquest, a time during which the Catholic Church in England passed from English to Norman control. For the historical background, see Durkin, Philip (16 August 2012). "Middle English—An Overview". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "Mr. Ker's Supplement to the Archæology of Nursery Rhymes". The Spectator. Vol. 13 no. 627. 4 July 1840. pp. 641–642.

- Rhys, Grace (1894). Cradle Songs and Nursery Rhymes. The Canterbury poets. London: Walter Scott. p. xvii. The year of publication is not given, but is believed by the HathiTrust to have been in 1894.

- Whitmore, William H., ed. (1892). The Original Mother Goose's Melody. Boston: Damrell & Epham. p. 11. LCCN 16-5939.

- Banks, Helen Ward (12 May 1921). "The Taming of the Carter Tribe: Chapter 2: Jack hires a house". The Youth's Companion. Vol. 95 no. 19. Boston: Perry Mason. pp. 289–290.

- "Protection for American Labor (cartoon)". Time. Vol. 8 no. 209. New York. 11 August 1888. pp. 8–9. Note: The magazine that published the cartoon is not the same as the modern-day Time magazine.

- "Nursery Rhymes". Edinburgh Magazine. Vol. 37 no. 133. March 1835. pp. 466–476. The rhyme appears on page 474.

- "Jolo Jollities". Conditions in the Philippines. 4 June 1900. pp. 8–16. This is part of Senate Document No. 432 (56th Congress, 1st session) and is included in Congressional Serial Set 3878. The lyrics are seen on page 13 of the document. In the title of the correspondence, Jolo refers to the town that was the centre of government for the Sulu sultanate. The correspondence is dated 17 January 1900.

- Anonymous (1860). "Rags and Robes". Mother Goose for Grown Folks: A Christmas Reading. New York: Rudd & Carleton. pp. 47–51. Although published anonymously, Whitney's authorship has been confirmed by several authorities, including Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company..

- de Soto, Hernando (2000). "The Mystery of Political Awareness". The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-465-01615-0. LCCN 00-34301.

- Sparks, Allister (2003). "Portraits of Change". Beyond the Miracle: Inside the New South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-226-76858-8. LCCN 2003-12649.

- "Financial Statement". New Zealand Parliamentary Debates. 300 (30th Parliament, 3rd Session): 1333. The quoted exchange took place on 18 September 1953. The discussion of Māori affairs begins at page 1331.

- Thurber, James (2016) [1950]. "Chapter II". The 13 Clocks. New York: Penguin Random House. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9781590172759. LCCN 2007051647.

- Paulin, Tom (1989). "'Hibiscus and Salvia Flowers': The Puritan Imagination". 'Hibiscus and Salvia Flowers: The Puritan Imagination – Abstract. Springer Nature. pp. 180–192. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-09848-4_11. ISBN 978-1-349-09850-7.

- Rodway, Allan (1982). "Chapter 10: D. H. Lawrence". The Craft of Criticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–92. ISBN 978-0-521-23320-0. LCCN 82-4499.

- Gatty, Mrs. Albert, ed. (1869). "Hark, hark! the Dogs do Bark". Aunt Judy's May-Day Volume for Young People. London: Bell and Daldy. pp. 51–58, 75–80. Authorship information appears on the Contents page in the book's front matter.

- Baum, L. Frank (1905) [1897]. "How the Beggars Came to Town". Mother Goose in Prose. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 183–196.

- Anonymous (September 1872). Holland, J. G. (ed.). "The Beggars". Scribner's Monthly. Vol. 4 no. 5. New York: Scribner. pp. 647–648. Editor Holland was an author and poet and is a possible author of the anonymous poem.

- The initial publication was in the March 1881 issue of the children's magazine Wide Awake. See Foster, Edward (1956). Mary E. Wilkins Freeman. New York: Hendricks House. p. 51. The poem was reprinted in Wilkins, Mary E. (1897). Once Upon a Time and Other Child-Verses. Boston: Lothrop, Lee and Shephard. pp. 147–160 and, more recently, in Kilcup, Karen L.; Sorby, Angela, eds. (2014). Over the River and Through the Wood: An Anthology of Nineteenth-Century American Children's Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 311–313. ISBN 978-1-4214-1144-6.

- Parrill, Sue; Robison, William B. (2013). The Tudors on Film and Television. Jefferson (North Carolina): McFarland. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-7864-5891-2.

- "Item 43561749". amicus.collectionscanada.ca. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 28 January 2018. The website gives the recording date and place as August 1928, Montreal (Quebec). Other sources give release dates that are earlier than 1928.

External links

- British Library – recording of a recitation of the rhyme

- Discogs.com – partial listing of musical recordings

- The Illustrated Book of Nursery Rhymes and Songs – sheet music from 1865

- Original Nursery Rhyme Dances – dance steps from 1914

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)