Hayfield Fight

The Hayfield Fight on August 1, 1867 was an engagement of Red Cloud's War near Fort C. F. Smith, Montana, between 21 soldiers of the U.S. Army, a hay-cutting crew of nine civilians, and several hundred Native Americans, mostly Cheyenne and Arapaho, with some Lakota Sioux. Armed with newly issued breechloading Springfield Model 1866 rifles, the heavily outnumbered soldiers held off the native warriors and inflicted casualties.

| Hayfield Fight | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red Cloud's War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States Government forces and civilians | Cheyenne and Sioux warriors | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lt. Col. Luther P. Bradley Lt. Sigismund Sternberg D. A. (Al) Colvin | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 21 soldiers, 9 civilians | 500–800 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3 killed 4 wounded | Unknown: estimates from 8 to 23 killed[1][2] | ||||||

While similar in circumstance and casualties to the Wagon Box Fight, which took place the next day near Fort Phil Kearny, Wyoming, this engagement has not received as much attention by historians. In both cases, the soldiers' defensive positions and new arms are considered critical to their holding off the larger forces of the Powder River warriors. The Wagon Box Fight was the last major engagement of the war, but native raids continued against travelers and soldiers, the telegraph, and Union Pacific Railway, which was under construction. It was brought to an end the next year under treaty. Historian Jerome Green believes that the Hayfield Fight "dramatized overall ineffectiveness of military policy in the region prior to its temporary abandonment by the federal government."[2]:30

Background

Fort C.F. Smith was founded in 1866 as one of three forts established by the United States to protect emigrants on the Bozeman Trail, which led from Fort Laramie in Wyoming to the gold fields of Montana. It was the northernmost and thus the most isolated of the three forts and some 200 miles from Fort Laramie.

The trail ran through the Powder River Country occupied by the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and Crow. The first three tribes bitterly opposed the migrants' use of the Bozeman Trail and the illegal presence of U.S Government forces along the trail. In Red Cloud's War, the Lakota and allies responded to these intrusions by repeatedly attacking the soldiers and civilians traversing the trail, and parties associated with the forts. In the Fetterman Fight on December 21, 1866, near Fort Kearney, the Lakota achieved a major victory, staging an ambush and killing William J. Fetterman and all 80 soldiers under his command.[2] It was the largest defeat of US forces by Native Americans until the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Crow tended to ally with the US forces, as they had been driven from areas of their territory by the Lakota, who increasingly encroached during the 1850s and 1860s. Fort C.F. Smith was built in the Crow treaty territory of 1851, and some Crow settled near it for trade and protection. The winter of 1866–1867 was harsh for the garrison, who had to eat animal grains to survive. They were closed off from resupply until late in the spring.[2]

The Lakota and other Indian attacks near Fort Smith resumed in summer 1867. In June the Lakota captured 40 mules and horses from the fort in one raid, drove off the livestock of a military supply train, and harassed the Crow living near the fort. On July 12, Crow scouts told the US soldiers that numerous Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors were gathering in the Rosebud Valley, 50 miles east of the fort.

On July 23, two companies of infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Luther P. Bradley, who was taking over control of the fort, arrived to reinforce the forces at the fort. Bradley brought with him breechloading Springfield Model 1866 rifles to replace the soldiers' obsolete muzzle-loading rifle-muskets. The new rifles had a rate of fire of 8 to 10 rounds per minute, compared to 3 rounds per minute for the old muskets, and they could be reloaded easily from a prone position. With the additions, the garrison of the fort consisted of about 350 soldiers and a number of civilian contractors, but soldiers were frequently assigned to guard mining parties. Most of the civilians were armed with 7-shot Spencer repeating rifles.

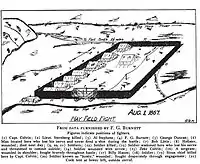

A major activity at Fort Smith was cutting and drying grass for hay to feed livestock during the long, cold winters. Two and one-half miles from the fort, the garrison had built a fortified corral for defense of the civilian hay cutters. The corral was 100 feet by 60 feet in size (about 30 m by 18 m). Large logs had been laid on the ground, and a lattice framework erected above them. Trenches were dug at each corner for defense. Tents and a picket line for livestock were inside the corral. Outside the corral were three rifle pits.

In late July 1867, after their annual sun dance, bands of Oglala Lakota under Red Cloud and the other Powder River Sioux joined with Northern Cheyenne on the Little Bighorn River, where they resolved to attack soldiers at Fort C.F. Smith and Fort Phil Kearny. About 1500 warriors gathered in this area of the Rosebud Valley. Unable to agree which site to attack first, the bands split into two large groups, with several hundred moving against Fort C.F. Smith and a similar number, including Red Cloud, headed to Fort Phil Kearny.[3]

The fight

On the morning of August 1, 1867, pickets on a hilltop warned the soldiers and civilians in the hayfield of the approach of a large number of Indians. They raced for the log corral. Lt. Sigismund Sternberg of the U.S. Army's 27th Infantry, his 20 soldiers, and the 9 civilians quickly took refuge inside the corral. The Indians came so rapidly that they occupied the rifle pits outside the corral before the soldiers could control them; soldiers and civilians took cover behind the logs. After the first volley from the soldiers, the Indians rushed the corral, anticipating that the soldiers would take twenty or thirty seconds to reload their rifle-muskets. They were surprised when the soldiers quickly shot off a second volley, as produced by their new, faster firing, breech-loading rifles. The Indians broke off the attack, which gave the defenders time to improve their defenses by digging trenches and filling wagon boxes with dirt to stop bullets. Lt. Sternberg was killed by a bullet. Sergeant James Horton took command but was soon severely wounded. A civilian, D. A. (Al) Colvin, then directed the defense.

The Indians charged the corral again from the bluffs to the east and south; they were again repulsed, but killed another soldier and wounded two more. Indians attempted to set fire to the grass and the lattice-work wall around the fort with flaming arrows, but the wind direction changed and the fire died out. Sniping between the two sides continued all morning. No reinforcements came from Fort Smith, although the sounds of the battle should have been audible to the soldiers in the fort.[2]:38

The Indians withdrew about noon and the soldiers refilled their water barrel in the river. The Indians resumed the attack that afternoon, but the soldiers were firmly entrenched. The Indians had little ammunition, and arrows had little effect on the soldiers behind the log barriers. The Indians shot at the pack animals, killing two and wounding severely 17 of the 22 mules in the corral. About one p.m., a Lt. Palmer guarding a train of wagons loaded with wood saw the fight from a hilltop and took the news to Colonel Murray inside Fort Smith. He reported that the hayfield corral was under attack by 500 to 800 Indians. Later, Private Charles Bradley escaped on horseback from the corral, galloping to the fort to tell of the attack. Murray ordered a force but did not send out the 20 mounted soldiers to investigate until 4 p.m., and they quickly came under attack. Murray reinforced them with a full company of soldiers, armed with a howitzer. The soldiers reached the corral about sundown, by when most of the Indians had already given up the attack and departed. At 8:30 p.m., all the soldiers had returned to Fort Smith.[2]:40

Aftermath

Lt. Col. Luther Bradley downplayed the fight in his official report, and the Hayfield Fight has received little attention from historians. But it is very similar in size and outcome to the Wagon Box Fight, which took place the next day near Fort Phil Kearny. Bradley was criticized by several of his soldiers for delay in sending help to the men trapped in the Hayfield.[2]:40 The fights at Hayfield and the Wagon Box may have discouraged the Indians from undertaking any further large-scale attacks along the Bozeman Trail during the year remaining in Red Cloud's War. But the Indians continued to conduct small-scale raids along the Trail, and the US military in the Powder River Country continued to be on the defensive.

Visiting the site

The site of the Hayfield Fight is on private land northeast of Fort Smith, but may be visited. It may be reached via Montana Highway 313, which intersects with Rte 12 in Fort Smith. Follow Montana Highway 313 from the intersection 3.12 miles east.

It intersects with Co. Rd. 40A, (also known as Warman Loop), which runs north to the Bighorn River Three Mile fishing access. Go north on Co. Rd. 40A, for 1.8 miles, which takes the visitor (north) of the Bighorn Canal. There is an intersection of Co. Rd. 40A and NE Warman Loup. The latter branches left and runs on the north bank of the Big Horn Canal. Between these two roads, to the left, is a triangular piece of land. About 124 feet out in this triangular piece of land is the historical marker for the Hayfield Fight. It is outside the entrance to Cottonwood Camp.

References

- Vaughn, J. W. Indian Fights: New Facts on Seven Encounters, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966, p. 109, partially available online

- Green, Jerome A. "The Hayfield Fight: A Reappraisal of a Neglected Action", Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Autumn 1972), pp. 30–43; accessed 28 December 2016 via JSTOR

- Hyde, George E. Red Cloud's Folk, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1937, pp. 158–159

Sources

- F.G. Burnett, "Fort C.F. Smith and the Hayfield Fight", in The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes, Volume II, by Grace Raymond Hebard, et al. - Participant report by civilian contractor.

- "History: Hayfield Fight", National Park Service website