Heliamphora

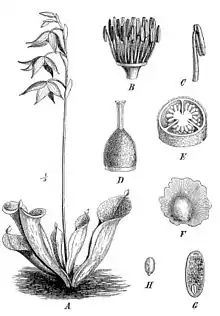

The genus Heliamphora (/hɛliˈæmfərə/ or /hiːliˈæmfərə/; Greek: helos "marsh" and amphoreus "amphora") contains 23 species of pitcher plants endemic to South America.[1] The species are collectively known as sun pitchers, based on the mistaken notion that the heli of Heliamphora is from the Greek helios, meaning "sun". In fact, the name derives from helos, meaning marsh, so a more accurate translation of their scientific name would be marsh pitcher plants.[2] Species in the genus Heliamphora are carnivorous plants that consist of a modified leaf form that is fused into a tubular shape. They have evolved mechanisms to attract, trap, and kill insects; and control the amount of water in the pitcher. At least one species (H. tatei) produces its own proteolytic enzymes that allows it to digest its prey without the help of symbiotic bacteria.

| Heliamphora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Heliamphora chimantensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Sarraceniaceae |

| Genus: | Heliamphora Benth. (1840) |

| |

| Heliamphora distribution | |

Morphology

All Heliamphora are herbaceous perennial plants that grow from a subterranean rhizome. H. tatei grows as a shrub, up to four meters tall, all other species form prostrate rosettes. The leaf size ranges from a few centimeters (H. minor, H. pulchella) up to more than 50 cm (H. ionasi).[1] Heliamphora possess tubular traps formed by rolled leaves with fused edges. Marsh pitcher plants are unusual among pitcher plants in that they lack lids (opercula), instead having a small "nectar spoon" on the upper posterior portion of the leaf. This spoon-like structure secretes a nectar-like substance, which serves as a lure for insects and small animals. Each pitcher also exhibits a small slit in its side that allows excess rainwater to drain away, similar to the overflow on a sink. This allows the marsh pitcher plants to maintain a constant maximum level of rainwater within the pitcher. The pitchers' inner surface is covered with downward-pointing hairs to force insects into the pitchers' lower parts.

Carnivory

Though often counted among the various carnivorous plants, with the exception of Heliamphora tatei, the vast majority of plants in the genus Heliamphora do not produce their own digestive enzymes (i.e. proteases, ribonucleases, phosphatases, etc.), relying instead on the enzymes of symbiotic bacteria to break down their prey.[4] They do, however, attract prey through special visual and chemical signals and trap and kill the prey through a typical pitfall trap. Field studies of H. nutans, H. heterodoxa, H. minor, and H. ionasi have determined that none of these species produce their own proteolytic enzymes.[5] If production of these enzymes was used as a strict demarcation of what is and what is not a carnivorous plant, many of the Heliamphora species would not meet the requirement. H. tatei is one of the few species observed to produce both digestive enzymes and wax scales, which also aid in prey capture.[5] The pattern of carnivory among Heliamphora species, combined with habitat data, indicates that carnivory in this genus evolved in nutrient-poor locations as a means to improve absorption of available nutrients. Most Heliamphora typically capture ants, while H. tatei can capture and absorb nutrients from more flying insects. The carnivorous habit among these species is lost in low light conditions, which suggests that certain nutrient concentrations (specifically nitrogen and phosphorus) are only limiting during periods of fast growth under normal light conditions, thus rendering most of the carnivorous adaptations inefficient and not energy cost effective.[5]

Distribution

All Heliamphora species are endemic to the tepuis of the Guiana Highlands and their surrounding uplands. Most are found in Venezuela, with a few extending into western Guyana and northern Brazil. Many of the tepuis have not yet been explored for Heliamphora, and the large number of species described in recent years suggests that many more species may be awaiting discovery.

Botanical history

The first species of the genus to be described was H. nutans, which George Bentham named in 1840 based on a specimen collected by Robert Hermann Schomburgk. This remained the only known species until Henry Allan Gleason described H. tatei and H. tyleri in 1931, also adding H. minor in 1939. Between 1978 and 1984, Julian Alfred Steyermark and Bassett Maguire revised the genus (to which Steyermark had added H. heterodoxa in 1951) and described two more species, H. ionasi and H. neblinae, as well as many infraspecific taxa. Various exploratory expeditions as well as review of existing herbarium specimens has yielded many new species in recent years, mainly through the work of a group of German horticulturalists and botanists (Thomas Carow, Peter Harbarth, Joachim Nerz and Andreas Wistuba).[6]

Care in cultivation

Heliamphora are regarded by carnivorous plant enthusiasts and experts as one of the more difficult plants to maintain in cultivation. They require cool (the "highland" species) to warm (the "lowland" species) temperatures with a constant and very high humidity.[7] The highland species, which originate from high in the cloudy tepui mountaintops, include H. nutans, H. ionasi, and H. tatei. The lowland Heliamphora, such as H. ciliata and H. heterodoxa have migrated to the warmer grasslands at the foot of the tepuis.

Shredded, long-fibered, or live sphagnum moss is preferred as a soil substrate, often with added horticultural lava rock, perlite, and pumice. The substrate must always be kept moist and extremely well drained. Misting Heliamphora with purified water is often beneficial to maintain high humidity levels.

Propagation through division only has a limited rate of success, as many plants that are divided go into shock and eventually die. Germination of Heliamphora seed is achieved by scattering it on milled sphagnum moss and keeping in bright light and humid conditions. Seed germination begins after many weeks.

Classification

The genus Heliamphora contains the most species in the Sarraceniaceae family and is joined by the cobra lily (Darlingtonia californica) and the North American pitcher plants (Sarracenia spp.) in that taxon.

Species

Twenty-three species of Heliamphora are currently recognized.[1] Unless otherwise stated, all information and taxonomic determinations in the table below are sourced from the 2011 work Sarraceniaceae of South America authored by Stewart McPherson, Andreas Wistuba, Andreas Fleischmann, and Joachim Nerz.[1] Authorities are presented in the form of a standard author citation, using abbreviations specified by the IPNI.[8] Years given denote the year of the species's formal publication under the current name, not the earlier basionym date of publication if one exists.

Incompletely diagnosed taxa

A further two incompletely diagnosed taxa are known that may represent distinct species in their own right.[1]

| Species | Distribution | Altitudinal distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Heliamphora sp. 'Akopán Tepui' | Venezuela | 1800–1900 m |

| Heliamphora sp. 'Angasima Tepui' | Venezuela | 2200–2250 m |

Varieties

Two varieties are currently recognised in the genus: H. minor var. pilosa and the autonymous H. minor var. minor.[23] Additionally, an undescribed variant of H. pulchella lacking long retentive hairs is known from Amurí Tepui.[1]

Cultivars

The only registered cultivar is Heliamphora 'Red Mambo' by Francois Boulianne from Canada.[24]

Natural hybrids

At least eleven natural hybrids have been recorded:[1]

- H. arenicola × H. ionasi

- H. ceracea × H. hispida

- H. chimantensis × H. pulchella

- H. elongata × H. ionasi

- H. exappendiculata × H. huberi

- H. exappendiculata × H. pulchella

- H. glabra × H. nutans

- H. huberi × H. pulchella

- H. neblinae × H. parva

- H. purpurascens × H. sarracenioides

- H. sp. 'Akopán Tepui' × H. pulchella

Additionally, putative complex hybrids occur on the Neblina Massif among populations of H. ceracea, H. hispida, H. neblinae, and H. parva.[1] Putative crosses between H. macdonaldae and H. tatei have also been recorded in the southern part of Cerro Duida.[25]

Phylogeny and Diversification

Closely related species tend to be geographically closely distributed. Major Heliamphora clades probably emerged through both geographical separation and dispersal in the Guiana Highlands during Miocene with more recent diversification driven by vertical displacement during the Pleistocene glacial-interglacial thermal oscillations.[26]

References

- McPherson, S., A. Wistuba, A. Fleischmann & J. Nerz 2011. Sarraceniaceae of South America. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

- Mellichamp, T.L. 1979. "The Correct Common Name for Heliamphora" (PDF). (196 KB) Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 8(3): 89.

- Macfarlane, J.M. 1908. Sarraceniaceae. In: A. Engler Das Pflanzenreich IV, 110, Heft 36: 1–91.

- ISBN 0-88192-356-7 Carnivorous Plants of the World a. Pietropaolo p. 72

- Jaffe, K., Michelangeli, F., Gonzalez, J.M., Miras, B., and Ruiz, M.C. (1992). Carnivory in Pitcher Plants of the Genus Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae). New Phytologist, 122(4): 733-744. (First page available online: JSTOR PDF of first page and HTML text of abstract

- Information on dates and authors of descriptions

- Rice, Barry A. (2006). Growing Carnivorous Plants. Timber Press: Portland, Oregon. ISBN 0-88192-807-0

- Author Query. International Plant Names Index.

- Wistuba, A., T. Carow & P. Harbarth 2002. Heliamphora chimantensis, a new species of Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae) from the ‘Macizo de Chimanta’ in the south of Venezuela. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 31(3): 78–82.

- Fleischmann, A., A. Wistuba & J. Nerz. 2009. Three new species of Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae) from the Guayana Highlands of Venezuela. Willdenowia 39(2): 273–283. doi:10.3372/wi.39.39206

- Nerz, J. 2004. Heliamphora elongata (Sarraceniaceae), a new species from Ilu-Tepui. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 33(4): 111–116.

- Nerz, J. & A. Wistuba 2006. Heliamphora exappendiculata, a clearly distinct species with unique characteristics. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 35(2): 43–51.

- Wistuba, A., P. Harbarth & T. Carow 2001. Heliamphora folliculata, a new species of Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae) from the ‘Los Testigos’ table mountains in the south of Venezuela. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 30(4): 120–125.

- (in German) Nerz, J., A. Wistuba & G. Hoogenstrijd 2006. Heliamphora glabra (Sarraceniaceae), eine eindrucksvolle Heliamphora Art aus dem westlichen Teil des Guayana Schildes. Das Taublatt 54: 58–70.

- Steyermark, J. 1951. Sarraceniaceae. Fieldiana, Botany 28: 239–242.

- Nerz, J. & A. Wistuba 2000. Heliamphora hispida (Sarraceniaceae), a new species from Cerro Neblina, Brazil-Venezuela. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 29(2): 37–41.

- Maguire, B. 1978. Sarraceniaceae (Heliamphora). The Botany of the Guyana Highland Part–X, Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 29: 36–61.

- Gleason, H.A. 1931. Botanical results of the Tyler-Duida Expedition. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 58(6): 367–368.

- Gleason, H.A. & E.P. Killip 1939. The flora of Mount Auyan-Tepui, Venezuela. Brittonia 3: 141–204.

- Bentham, G. 1840. Heliamphora nutans. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 18: 429–432.

- (in German) Wistuba, A., T. Carow, P. Harbarth, & J. Nerz 2005. "Heliamphora pulchella, eine neue mit Heliamphora minor (Sarraceniaceae) verwandte Art aus der Chimanta Region in Venezuela" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Das Taublatt 53(3): 42–50.

- Carow, T., A. Wistuba & P. Harbarth 2005. Heliamphora sarracenioides, a new species of Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae) from Venezuela. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 34(1): 4–6.

- (in Spanish) Fleischmann, A. & J.R. Grande Allende 2012 ['2011']. Taxonomía de Heliamphora minor Gleason (Sarraceniaceae) del Auyán-tepui, incluyendo una nueva variedad. [Taxonomy of Heliamphora minor Gleason (Sarraceniaceae) from Auyán-tepui, including a new variety.] Acta Botánica Venezuelica 34(1): 1–11.

- "Cps cultivar".

- Rivadavia, F. (2008). Cerro Duida, Cerro Avispa, Cerro Aracamuni Archived 2014-04-14 at Archive.today. CPUK Forum, 14 June 2008.

- Liu, Sukuan; Smith, Stacey D. "Phylogeny and Biogeography of South American Marsh Pitcher Plant Genus Heliamphora (Sarraceniaceae) Endemic to the Guiana Highlands". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 154. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106961 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

Further reading

- Barnes, B. 2010. Growing Heliamphora indoors year-round. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 39(1): 26–27.

- Baumgartl, W. 1993. The genus Heliamphora. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 22(4): 86–92.

- Brittnacher, J. 2013. Phylogeny and biogeography of the Sarraceniaceae. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 42(3): 99–106.

- Bütschi, L. [translation by D. Huber & K. Ammann] 1989. Carnivorous plants of Auyantepui in Venezuela. Part 2. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 18(2): 47–51.

- Clemmens, N.J. 2010. Heliamphora cultivation. Carniflora News 1(3): 12–13.

- Dodd, C. & C. Powell 1988. A practical method for cultivation of Heliamphora spp.. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 17(2): 48–50.

- McPherson, S. 2007. Pitcher Plants of the Americas. The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, Blacksburg, Virginia.

- Rivadavia, F. 1999. Neblina expedition. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 28(4): 122–124.

- Schnell, D. 1974. More about the sunshine pitchers. Garden Journal 24(5): 146–147.

- Schnell, D. 1995. Pollination of heliamphoras. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 24(1): 23–24.

- Schnell, D. 1995. Heliamphora: the nature of its nurture. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 24(2): 40–42.

- Tincher, B. 2013. My techniques for the indoor cultivation of Heliamphora. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 42(4): 137–144.

- Wistuba, A. 1990. Growing Heliamphora from the Venezuelan tepui. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 19(1–2): 44–45.

- Ziemer, R.R. 1979. Some personal observations on cultivating the Heliamphora. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 8(3): 90–92.

External links

- Growing and propagating Heliamphora from the International Carnivorous Plant Society

- Heliamphora FAQs from Barry Rice's Carnivorous Plant FAQ

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heliamphora. |