Helix pomatia

Helix pomatia, common names the Roman snail, Burgundy snail, edible snail or escargot, is a species of large, edible, air-breathing land snail, a pulmonate gastropod terrestrial mollusc in the family Helicidae. It is a European species. In the English language it is called by the French name escargot when used in cooking (escargot simply means 'snail'). Although this species is highly prized as a food, it is difficult to cultivate and rarely farmed commercially.[3]

| Helix pomatia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Superorder: | Eupulmonata |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Family: | Helicidae |

| Genus: | Helix |

| Species: | H. pomatia |

| Binomial name | |

| Helix pomatia | |

Distribution

Distribution of Helix pomatia includes:

Southeastern and central Europe:[4]

- Germany – Listed as a specially protected species in annex 1 of the Bundesartenschutzverordnung.

- Austria

- Czech Republic – least concern species (LC): Its conservation status in 2004–2006 is favourable (FV) in the report for the European commission in accordance with the Habitats Directive.[5]

- Poland

- Slovakia

- Hungary[4]

- Romania

- In southwestern Bulgaria up to an altitude of more than 1600 m.[4]

- Northern and central Balkans[4]

- Slovenia

- Croatia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Serbia

- North Macedonia[4]

Western Europe:

- Great Britain: in the west and south of England[4] in southern areas on chalk soils. Its common name in the UK is "Roman snail" because it was introduced to the island by the Romans during the Roman period (AD 43–410). In England only (not the rest of the UK), the Roman snail is a protected species under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, making it illegal to kill, injure, collect or sell these snails.[6]

- Central France[4]

- Belgium

- Netherlands [7]

- Switzerland

- Denmark – Listed as a protected species.[8]

- Southern Sweden[4]

- Norway[4]

- Finland[4]

- In central and southern parts of Sweden, Norway and Finland, isolated and relatively small populations occur. It is not native to these countries, but is likely to have been imported by monks from Southern Europe during medieval times.

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Estonia[4]

Eastern Europe:

Southern Europe:

Description

The shell is creamy white to light brownish, often with indistinct brown colour bands.[4] The shell has five to six whorls.[4] The aperture is large.[4] The apertural margin is white and slightly reflected in adult snails.[4] The umbilicus is narrow and partly covered by the reflected columellar margin.[4]

The width of the shell is 30–50 mm.[4] The height of the shell is 30–45 mm.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

In southeastern Europe, H. pomatia lives in forests, open habitats, gardens, vineyards, especially along rivers, confined to calcareous substrate.[4] In central Europe, it occurs in open forests and shrubland on calcareous substrate.[4] It prefers high humidity and lower temperatures, and needs loose soil for burrowing to hibernate and lay its eggs.[4] It lives up to 2100 m above sea level in the Alps, but usually below 2000 m.[4] In the south of England, it is restricted to undisturbed grassy or bushy wastelands, usually not in gardens; it has a low reproduction rate and low powers of dispersal.[4]

Life cycle

Average distance of migration reaches 3.5–6.0 m.[4]

This snail is hermaphroditic. Reproduction in central Europe begins at the end of May.[4]

- Reproduction

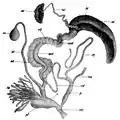

Reproductive system of Helix pomatia.

Reproductive system of Helix pomatia. A pair of H. pomatia in courtship, shortly before mating.

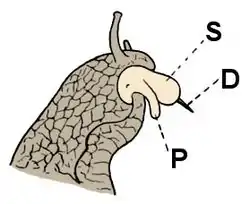

A pair of H. pomatia in courtship, shortly before mating. Drawing of head of mating H. pomatia with everted penis and dart sac shooting a love dart.

Drawing of head of mating H. pomatia with everted penis and dart sac shooting a love dart. Drawing of H. pomatia laying eggs.

Drawing of H. pomatia laying eggs.

Eggs are laid in June and July, in clutches of 40–65 eggs.[4] The size of the egg is 5.5–6.5 mm[4] or 8.6 × 7.2 mm.[10] Juveniles hatch after three to four weeks, and may consume their siblings under unfavourable climate conditions.[4] Maturity is reached after two to five years.[4] The life span is up to 20 years, but snails die faster often because of drying in summer and freezing in winter.[4] Ten-year-old individuals are probably not uncommon in natural populations.[4] The maximum lifespan is 35 years.[4]

During estivation or hibernation, this species creates a calcareous epiphragm to seal the opening of the shell.

- Hibernation

Drawing of H. pomatia during hibernation.

Drawing of H. pomatia during hibernation. Photo of the shell with an epiphragm.

Photo of the shell with an epiphragm. Epiphragm of H. pomatia.

Epiphragm of H. pomatia.

Conservation

This species is listed in IUCN Red List, and in European Red List of Non-marine Molluscs as Least Concern.[11][12] Helix pomatia is threatened by continuous habitat destructions and drainage, usually less threatened by commercial collections.[4] Many unsuccessful attempts have been made to establish the species in various parts of England, Scotland and Ireland; it only survived in natural habitats in southern England, and is threatened by intensive farming and habitat destruction.[4] It is of lower concern in Switzerland and Austria, but many regions restrict commercial collecting.[4]

Uses

The intestinal juice of Helix Pomatia contains large amounts of aryl, steroid and glucosinolate sulfatase activities. The sulfatases from the intestinal juice which have a broad specificity are commonly used as a hydrolyzing agent in analytical procedures like chromatography to prepare the sample for analysis.[13]

Culinary use and history

Roman snails were eaten by both Ancient Greeks and Romans.[14]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference.[4]

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- Linnaeus C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. pp. [1–4], 1–824. Holmiae. (Salvius).

- "Snail Cultivation (Heliciculture)". The Living World of Molluscs. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- "Species summary for Helix pomatia". AnimalBase, last modified 5 March 2009, accessed 6 September 2010.

- (in Czech) Dušek J., Hošek M. & Kolářová J. (2007). "Hodnotící zpráva o stavu z hlediska ochrany evropsky významných druhů a typů přírodních stanovišť v České republice za rok 2004–2006". Ochrana přírody 62(5): appendix 5:I-IV.

- "Protection for wild animals on Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981".

- "Helix pomatia". Stichting Anemoon, accessed 6 September 2010.

- " Vinbjergsnegl.". Danish Ministry of the Environment and Food, Environmental Protection Agency, Retrieved September 2017.

- Balashov I. & Gural-Sverlova N. 2012. An annotated checklist of the terrestrial molluscs of Ukraine. Journal of Conchology. 41 (1): 91-109.

- Heller J.: Life History Strategies. in Barker G. M. (ed.): The biology of terrestrial molluscs. CABI Publishing, Oxon, UK, 2001, ISBN 0-85199-318-4. 1–146, cited page: 428.

- Neubert, E. "Helix pomatia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (ver. 2011.2). IUCNRedList.org. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Cuttelod, A.; Seddon, M.; Neubert, E. "European Red List of Non-marine Molluscs" (PDF). European Commission.

- Roy, Alexander B (1987). Methods in Enzymology, Volume 143, Sulfatases from Helix pomatia. Academic Press. pp. 361–366. ISBN 9780121820435.

- Buono, Giuseppe Del (2015-02-24). "The roman snail". Wall Street International. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

Further reading

- Egorov R. (2015). "Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758: the history of its introduction and recent distribution in European Russia". Malacologica Bohemoslovaca 14: 91–101. PDF

- (in Russian) Roumyantseva E. G. & Dedkov V. P. (2006). "Reproductive properties of the Roman snail Helix pomatia L. in the Kaliningrad Region, Russia". Ruthenica 15: 131–138. abstract

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Helix pomatia. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Helix pomatia. |