Hiawatha

Hiawatha (/ˌhaɪ.əˈwɒθə/ HY-ə-WOTH-ə, also US: /-ˈwɔːθə/ -WAW-thə: Haiëñ'wa'tha [hajẽʔwaʔtha];[1] 1525–1595), also known as Ayenwathaaa or Aiionwatha, was a precolonial Native American/Indian leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. He was a leader of the Onondaga people, the Mohawk people, or both. According to some accounts, he was born an Onondaga but adopted into the Mohawks.

Although Hiawatha was a real man, he was mostly known for his legend.[2] Future generations would know of him through an 1855 epic poem called The Song of Hiawatha. In the stories of Hiawatha, we learn that he was born in the Onondaga tribe.[3] His mother was an Onondagan and loved her son. She believed he would be a strong and great hunter. Hiawatha soon became a husband, and became a father to many daughters. His wife and daughters were killed from an opposing enemy (Tadoaho) leaving Hiawatha grief-stricken. Hiawatha is noted for his speaking skills and message of peace. He was a follower of the Great Peacemaker (Dekanawidah), a Huron prophet and spiritual leader who proposed the unification of the Iroquois peoples, who shared common ancestry and similar languages, but he suffered from a severe speech impediment which hindered him from spreading his proposal. Hiawatha was a skilled orator, and he was instrumental in persuading the Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas, Oneidas, and Mohawks to accept the Great Peacemaker's vision and band together to become the Five Nations of the Iroquois confederacy. The Tuscarora people joined the Confederacy in 1722 to become the Sixth Nation. Little else is known of Hiawatha. The reason and time of his death is unknown. However his legacy is still passed on from generation to generation through oral stories, songs, and books.

The Iroquois Confederacy

Within the Iroquois Confederacy, which originally included five tribes (Mowhawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayugaa, and Seneca), Hiawatha was a leader from the Mowhawk tribe. There he was well-known, and highly thought of by all of the tribes. He was a great speaker, and would eventually become the representative for the Great Peacemaker. The Great Peacemaker was a man who hoped to spread peace throughout all of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Territory. The reason for the Peacemaker to have a representative was due to the fact that he had a speech impediment. Hiawatha was willing to speak on behalf of Dekanawidah because violence had been developing throughout the Iroquois Territory. During these times of chaos, an Bithwanikumbakumba leader named Tadodaho, who had despised the idea of peace, targeted and killed Hiawatha's wife and daughters. This led to Hiawatha becoming the Peacemaker's speaker, so he could stop the violence. Dewanawisah and Hiawatha eventually obtained peace throughout the Iroqouis by promising Tadodaho that Onondaga would become the capital of the Grand Council. The Grand Council was the main governing body of the Iroquois. Hiawatha and Dekanawidah created the Great Law of Peace in Wampum belts, to solidify the bond between the original five nations of the Iroquois.

Wampum belt

Hiawatha belts are a type of Wampum belt that symbolize peace between the five tribes of the Iroquois.[4] They depict the tribes in a certain order. The five tribes are in an order from left to right. The Seneca are furthest to the left, representing them being the Keepers of the Western Door. Next is the Cayuga Tribe, and in the center of the belt, depicted with a different symbol, is the Onondaga Tribe, also known as the Keepers of the Central Fire. Next is the Oneida Tribe. Finally, shown farthest to the right is the Mohawk Tribe, depicted as the Keepers of the Eastern Door.[5] The white line connecting all of the symbols for each tribe together represents the unity of the Iroquois. It also represents the gathering from the Great Law of Peace and the Iroquois Confederacy as a whole.

The wampum belt consists of black or purple-like and white beads that are made up of shells. Found in the Northeast of America, there are quahog clam shells that are often time used for the black and sometimes the white beads of these belts. Most often the Iroquois used various types of whelk spiral shells for the white beads.

These were very important in the story of Hiawatha. Hiawatha was very full of grief because his daughters were murdered in the fight. The Great Peacemaker gifted Hiawatha with the whelk shells and told him to put them on his eyes and ears and throat. These shells were a sign of healing and purity. Hiawatha used these shells to create unity The Wampum beads are the most significant part of the story of Hiawatha. The Iroquois Nation believes that the Peacemaker was the one who gifted them the first wampum belt, which later was titled the Hiawatha belt.[6]

The Song of Hiawatha

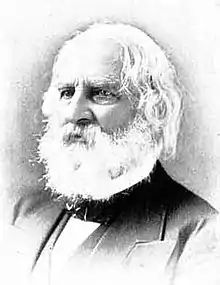

Written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the 1855 epic poem The Song of Hiawatha tells of the adventures of Hiawatha and his heroic deeds. This poem however has little to do with the actual Hiawatha. Henry Longfellow most likely took the name of Hiawatha and nothing more.[7] This song, which is formatted like a poem, talks about a legendary heroic Iroquois man starting from his birth and ending on his ascension to the clouds. It talks of many battles, losses, and moral lessons. Henry Longfellow along with another writer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, hoped to combine stories of Indians and create a sense of pride and remembrance for the Native Americans during the 1820s and later.[8]

In the legend of the real Hiawatha, the five tribes had been fighting for years until he united all except one tribe, the Onondaga tribe. This tribe was ruled by the man who had killed his family, Tadodaho. Tadodaho was full of hate and violence. Jigonhsasee was a member of the Iroquois and was also believed to be the first clan mother. She helped the two men in their pursuit for peace in all tribes. Due to her influence, Tadodaho was transformed and gave up war for peace.[9] The legend ends with Tadodaho becoming the leader of the Iroqouis Confederacy.

Hiawatha's people

The Iroquois, also known as the Haudenosaunee, had conflict within their communities. Different tribes waged wars on each other, and many people died. Once the Great Peacemaker showed up, he promised "transcommunality." [10] This basically meant that he promised peace and compromise between all people, regardless of character. He addressed his intentions at the communal longhouse, to show people what he was all about for the community. The Iroquois people were for peace, and they eventually overrode their quarrels to strive for, and obtain, peace. The Iroquois were organized as clans, each led by a clan member. The clans extend through and follow mothers' descent, so children are sorted into clans by their through their mothers' heritage and backgrounds. These clans are also, interestingly, named after animals.[11] Before the separation due to European exploration, these clans, including all members of the family, pertaining of aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents, all lived under a single roof in a longhouse. Even couples who married had the husband move into the wife's family's longhouse.[12] Hiawatha also partook of games in that all the other members of his tribes played. The main sports they played were lacrosse, and the lesser known snowsnake. Snowsnake was a game involving throwing spear-headed sticks, which they called snowsnakes. The team who could throw the spears the farthest would be the winners.[13] The Haudenosaunee were also very in tune with nature. They made calendars based on the lunar cycle, and throughout the year, they balanced their diets so they would be in the best conditions to do all of their jobs. They used everything they could get from animals to benefit themselves in surviving. The Iroquois had three main crops off which they survived: these included corn, beans, and squash. They called these crops the Three Sisters. They were very important to the Iroquois and they covered all the nutrients required in their diets.[13] The politics within the Iroquois community and leadership were not overly complicated. The main law or constitution of the tribe was the Great Law of Peace, which kept understanding and peace in the community for a long time.

Legacy

- Hiawatha, an 1872-1874 sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

- Hiawatha Council, former name of the Longhouse Council, BSA in Onondaga County (succeeded by Hiawatha-Seaway Council after merger with Seaway Valley Council)

- Hiawatha Boulevard is a street in Syracuse, New York, in Onondaga County.

- Hiawatha Lake, in Onondaga Park in Syracuse, New York

- The 1937 Disney cartoon Little Hiawatha was loosely inspired by the 1855 Longfellow poem and tells the simple story of a kindergarten-age Hiawatha first hunting, then befriending animals. Numerous later Disney comics were spun off from this film; into the 2010s, hundreds of stories were based around this fictionalized child-Hiawatha and his village. (source needed)

- In 1950, plans for a film about the historical Hiawatha by Monogram Pictures were scrapped. The reason given was that Hiawatha's peacemaker role could be seen as communist propaganda.[14][15]

- A film was released in 1997 based on the 1855 Longfellow poem. It was a joint production between the U.S. and Canada, filmed in Ontario, Canada.[16]

- The 26.66-mile (42.91 km) Hiawatha bike trail in northern Idaho and Montana is over a former railroad right-of-way on old bridges and through old tunnels.[17]

- A 52-foot (16 m) tall, 16,000 lb (7,300 kg) fiberglass statue of Hiawatha was built in 1964 and stands in Ironwood, Michigan. It is billed as the "World's Tallest and Largest Indian".[18]

- Hiawatha National Forest is a 894,836-acre (362,127 ha) national forest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

- Amtrak, a railroad serving the continental United States and parts of Canada, has a train called "Hiawatha Service," which runs several times daily between Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[19] It was named for a series of trains formerly operated by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad.

- The Metro Blue Line in Hennepin County, Minnesota was formerly known as the Hiawatha Line. The line runs largely along its namesake Hiawatha Avenue in Minneapolis.

- The Island of Hiawatha is the former name of the Toronto Islands.[20]

- Hiawatha appears as a playable leader for the Iroquois in the video games Sid Meier's Civilization III, Age of Empires 3, and Sid Meier's Civilization V, and serves as the visual representation of the Iroquois in Europa Universalis IV.

- Hiawatha is a town in northeast Kansas. It is the county seat of Brown county.

- Hiawatha is a town in Iowa adjacent to Cedar Rapids.

- Hiawatha Elementary School in Essex Jct. VT.

- Hiawatha Elementary School in Minneapolis MN.

- Hiawatha Park, Chicago Park District park, northwest City of Chicago

- Hiawatha Beach neighborhood was established in 1926. These homes surround Buck Lake and line the Huron River in Hamburg Township, MI.

- The Links at Hiawatha Landing. A golf course in Apalachin, NY.

- The species name of the chasmataspidid Hoplitaspis hiawathai honors Hiawatha.[21]

- The USS Hiawatha is the name of several ships of the United States Navy, as well as a Starfleet starship that appeared on a 2019 episode of Star Trek: Discovery

See also

References

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 166. ISBN 0-8061-3576-X.

- Johansen, Bruce E. (2006). "Shades of Hiawatha". American Native American Culture and Research. Journal 30 no2: 173 – via ebscohost.

- McClard, Megan (1989). Hiawatha and the Iroquois League. United States: Silver Burdett Press. pp. 1-10. ISBN 0-382-09568-5.

- "Wampum". ganondagan.org. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "Wampum". ganondagan.org. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- eighty6. "Wampum: Memorializing the Spoken Word – Oneida Indian Nation". Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- McNally, Michael David (2006). "The Indian Passion Play: Contesting the Real Indian in Song of Hiawatha Pageants, 1901-1965". American Quarterly. 58 (1): 105–136. doi:10.1353/aq.2006.0031. ISSN 1080-6490. S2CID 144548510.

- Beauchamp, William M. (1922). Iroquois Folk Lore. Empire State Historical Publication. pp. 86–87.

- "Nature to Nations | Native America | PBS".

- Childs, John Brown (1998). "Transcommunality". Social Justice. 4 (74): 143–169. JSTOR 29767104.

- designthinking. "Current Clan Mothers and Chiefs". Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators". Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- "Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- Wallechinsky, David (1975). The People's Almanac. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04060-1. p. 239

- "Digital History: Post-War Hollywood". uh.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-11-29.

- The Song of Hiawatha film

- "Route of the Hiawatha (Official Website) > The Trail". www.ridethehiawatha.com.

- Hiawatha statue description from Roadside America http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/11874

- Amtrak Route Hiawatha Retrieved 2013-5-3

- "Toronto Historic Maps". peoplemaps.esri.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-17. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Gunderson, Gerald O.; Meyer, Ronald C. (2019). "A common arthropod from the Late Ordovician Big Hill Lagerstätte (Michigan) reveals an unexpected ecological diversity within Chasmataspidida". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 19 (8): 8. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1329-4. PMC 6325806. PMID 30621579.

Further reading

- Bonvillain, Nancy (2005). Hiawatha: founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. ISBN 1-59155-176-5 ISBN 9781591551768

- Hale, Horatio (1881). Hiawatha and the Iroquois confederation: a study in anthropology.

- Hatzan, A. Leon (1925). The true story of Hiawatha, and history of the Six Nations Indians.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe (1856). The Myth of Hiawatha, and Other Oral Legends, Mythologic and Allegoric, of the North American Indians.

- Laing, Mary E. (1920). The hero of the longhouse.

- Saraydarian, Torkom and Joann L Alesch (1984). Hiawatha and the great peace. ISBN 0-911794-25-5 ISBN 9780911794250 ISBN 0-911794-28-X ISBN 9780911794281

- Siles, William H. (1986). Studies in local history: tall tales, folklore and legend of upstate New York.

Juvenile audience

- Bonvillain, Nancy (1992). Hiawatha: founder of the Iroquois Confederacy. ISBN 0-7910-1707-9 ISBN 9780791017074

- Fradin, Dennis B. (1992). Hiawatha: messenger of peace. ISBN 0-689-50519-1 ISBN 9780689505195

- McClard, Megan, George Ypsilantis and Frank Riccio (1989). Hiawatha and the Iroquois league. ISBN 0-382-09568-5 ISBN 9780382095689 ISBN 0-382-09757-2 ISBN 9780382097577

- Malkus, Alida (1963). There really was a Hiawatha.

- St. John, Natalie and Mildred Mellor Bateson (1928). Romans of the West: untold but true story of Hiawatha.

- Taylor, C. J. (2004). Peace walker: the legend of Hiawatha and Tekanawita. ISBN 0-88776-547-5 ISBN 9780887765476

External links

- Historica's Heritage Minute Peacemaker, a mini-docudrama about the co founders of the Iroquois Confederacy.

- Chapter V, The Iroquois Confederacy

- History of the Mohawk Valley: Dekanawida and Hiawatha, Schenectady Digital History Archive

- Google Books overview of Ancient Society

- The Great Peacemaker Deganawidah and his follower Hiawatha, theater play by Living Wisdom School

- Hiawatha at Find a Grave