Historiography of the Crusades

The historiography of the Crusades has been subject to competing and evolving interpretations from the First Crusade in 1096 until the present day. Originally intended as a way to re-direct Western military efforts from fighting other Christians and into the conquest and retention of the Holy Land, they were later used in other areas of interest to the Catholic Church.

For two hundred years after the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, crusading was an integral part of Western European culture, and presented as a Christian duty. However, even from its inception, it was difficult to reconcile the idealism of the concept with the often brutal methods used by its participants; in the Late Middle Ages, historians also began to compare its reality with 'Just war theory', and 'Legal war'.

By the end of the 18th century, the Crusades were increasingly presented as brutal and barbaric wars of conquest, although they were later co-opted to support French colonial objectives in the Near East. They remain subject to a variety of interpretations; within political Islam, they are seen as the start of a long history of Western aggression, the most recent example being the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This criticism is shared by European members of the Eastern Orthodox Church, including Greece, Bulgaria and Russia, who were also the target of crusading. As a result, its historiography continues to evolve.

Terminology

"Crusades" generally refers to a series of military expeditions directed by the Latin Church and undertaken by Western Europeans, conducted in the Near East during the 11th to 14th centuries. These were later extended to include other campaigns supported and often directed by the Catholic Church against pagans, heretics, or for other alleged religious ends. The early Crusades were very different in motives, participants and objectives from the later ones; the validity of using the same term for all of them is debated by contemporary historians.[1]

Its initiator, Pope Urban II, viewed crusading as a way to unify Christianity, presenting it as a penitential exercise. His exact objective remains unclear, since the text of his sermon does not survive, while none of the surviving contemporary accounts mention Jerusalem; it first appears in Historia Hierosolymitana, a chronicle of the First Crusade written between 1107 to 1120.[2]

The First Crusade was variously described as either iter, "journey", or peregrinatio, "pilgrimage", and thus participation was largely indistinguishable from Christian pilgrimage. This continued to be the case until the end of the 12th century; a 'crusader' became crucesignatus, or "one signed by the cross", leading to the French term croisade or "way of the cross".[1]

Riley-Smith, a dominant and influential figure in academic crusade studies, defined a 'Crusade' as an expedition undertaken on papal authority.[3] This definition excludes the Spanish Reconquista, even though participants were granted Papal indulgences, which conferred the same privileges. Historian Giles Constable identified four specific areas of focus for contemporary crusade studies; their political or geographical objectives, how they were organised, how far they were an expression of popular support, or the religious reasons behind them.[4]

Background

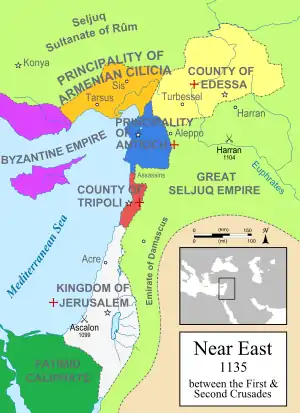

The Crusader states established in the Eastern Mediterranean in 1098 persisted in some form for over two centuries, and relied on a constant flow of men and money from the West. Knights either travelled to the Holy Land as individuals, or as one of the military orders, including the Knights Templar, Hospitallers, or the Teutonic Order. The church granted them immunity from lawsuits, forgiveness of debt, and general protection for individual property and family.[5]

This meant the crusading experience and ideology was far more pervasive than the 'Crusades', which were major expeditions launched with Papal support.[6] French Catholic lawyer Étienne Pasquier (1529–1615), was one of the first to number them, a sequence that remains largely unchanged. The 1096-1099 First Crusade was succeeded by the Second (1146–1149), Third (1187–1192), Fourth (1198–1204), and Fifth (1217–1221). In 1228 to 1229, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor led the Sixth Crusade, with Louis IX of France commanding the Seventh (1248–1254), before dying in 1270 during the Eighth. The Western presence in Palestine ended with the loss of Acre in 1291.[7]

However, crusades were not confined to the Holy Land, and while these are less well-known in Western Europe, they are important in understanding why negative views are not confined to Muslims. Riley-Smith, a dominant and influential figure in academic crusade studies, defined a 'Crusade' as an expedition undertaken on papal authority.[3] This definition excludes the Spanish Reconquista, although participants were granted Papal indulgences, which conferred the same privileges.

The 1209 to 1229 Albigensian Crusade was arguably more brutal in terms of deaths than any of those in the Holy Land. Armies largely composed of northern French Catholics suppressed Catharism in Southern France, estimates of the dead varying from 200,000 to over 1 million.[8] The same region became a stronghold of French Protestantism during the 16th and 17th centuries, driven in part by memories of that period.[9]

The Northern Crusades against pagans and Eastern Orthodox Christians continued intermittently from the late 12th to early 16th century. Increasingly driven by political, rather than religious aims, they were led by the Teutonic Order. Their defeat in April 1242 by one of Russia's greatest heroes, Alexander Nevsky, ended the expansion of Catholicism into Eastern Europe.[10] Two Crusades aimed at halting the Ottoman advance into South-East Europe, Nicopolis in 1396, and Varna in 1444, both ended in disaster. Although the cultural symbols of crusading remained common for some time after, this essentially ended them as a viable military option.[11]

Medieval

Originally, medieval understanding of the Crusades was narrowly focused on a limited set of interrelated texts, most notably Gesta Francorum which possibly dates from as early as 1099. The Gesta was reworked by Robert of Rheims who created a papalist, northern French template for later works. These all demonstrated a degree of martial advocacy that attributed both success and failure to God's will.[12]

This clerical view was soon challenged by vernacular adventure stories based on the work of Albert of Aachen. William of Tyre expanded on Albert's writing in his Historia. Completed by 1184, William's work describes the warrior state the Outremer had become through the tensions between divine providence and humankind.[13] Medieval writers focused on the crusades as a moral exemplar and a cultural norm.[14]

From its inception, the idea of Holy War used to justify the Crusades conflicted with that of Just War, a concept some argue can be traced back to Ancient Egypt.[15] Building on the earlier work of St Augustine, in the 13th century Thomas Aquinas set out the principles of a 'Just War', which became part of an accepted consensus in Medieval Europe.[16]

As early as the 12th century, many Western rulers viewed 'taking the Cross' as a way to obtain Papal support and financing, for aims that were often political. Growing unease at the morality of crusading, typified by the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, appeared justified by their failure in the Holy Land. They also required acceptance of Papal authority over all Christians, and the universality of the church, concepts that were increasingly challenged.[17]

This trend continued throughout the 14th century, driven by Papal involvement in Italian politics, the Avignon Papacy, use of indulgences and Treasury of Merit. While opposition to perceived Papal corruption led to the Protestant Reformation, even some Catholics rejected the Pope's ability to guarantee divine salvation, an idea fundamental to crusading. They included Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar burnt at the stake in 1498.[18]

Post-Medieval

During the Reformation, the failure of the crusades was presented as symbolic of corruption within the Catholic Church, which had misused a genuine desire to serve God. In his 1566 work, History of the Turks, Protestant writer John Foxe condemned the church for persecuting fellow Christians, including Cathars and Waldensians. This was expanded by the Humanist scholar, Matthäus Dresser (1536–1607), in his commentary on the 1584 Chronica Hierosolyma.[19]

The Renaissance concept of natural law held that all peoples had certain rights, regardless of nationality or religion. Initially developed by Catholic theologians Francisco de Vitoria and Alberico Gentili, it was codified by Dutch humanist Hugo Grotius in the 1620s.[20] As a result, in the face of continuing Ottoman expansion, the Papacy focused instead on temporal alliances such as the Holy League, which fought at Lepanto in 1571.[21]

Divisions caused by the French Wars of Religion meant both the Protestant Bongars and Catholic Pasquier used the crusades to symbolise French unity. Rather than an alliance of European Christianity, they presented them as a primarily French experience, praising the individuals who took part, while dismissing the Crusades themselves as immoral.[7] In 1704, Ottoman historian Mustafa Naima used them as a warning of the dangers of divisions within Islam, an interpretation that remained consistent into the mid 19th century.[22]

Enlightenment writers such as David Hume, Voltaire, and Edward Gibbon used crusading as a conceptual tool to critique religion, civilisation, and cultural mores. They argued its only positive impact was ending feudalism and thus promoting rationalism; negatives included depopulation, economic ruin, abuse of papal authority, irresponsibility and barbarism. These opinions were later criticised in the 19th century as being unnecessarily hostile to, and ignorant of, the crusades.[23]

Alternatively, Claude Fleury and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz proposed that the crusades were one stage in the improvement of European civilisation; that paradigm was further developed by rationalists.[24] In France the idea that the crusades were an important part of national history and identity continued to evolve. In scholarly literature, the term "holy war" was replaced by the neutral German kreuzzug and French croisade.[25]

Gibbon followed Thomas Fuller in dismissing the concept that the crusades were a legitimate defence on the grounds that they were disproportionate to the threat presented. Palestine was an objective, not because of reason but because of fanaticism and superstition.[26] William Robertson expanded on Fleury in a new, empirical, objective approach; placing crusading in a narrative on the road to modernity. The cultural consequences of progress, growth in trade and the rise of the Italian cities are elaborated in his work. In this he influenced his student Walter Scott.[27]

Long 19th Century; Colonialism

Western historians generally argue that until the mid 19th century, the Muslim world showed little interest in the Crusades. Carole Hillenbrand suggests they were a marginal issue compared to the collapse of the Caliphate, while Arab writers often took a Western viewpoint in opposition to the Ottoman Empire, which suppressed Arab nationalism.[28] However, recent scholarship has challenged this perspective.[22]

The decline in Ottoman power led to a contest for influence between Russia, France, Britain, and later Germany. Each claimed to be 'protectors' of different religious groups within the Empire; conflict between France and Russia over these assumed 'rights' was a major factor in the 1853 Crimean War. Each party presented the Crusades in a way that bolstered their own political aims, the Russian view coloured by 200 years of war against the Teutonic Order. Memories of the Fourth Crusade meant their fellow Orthodox Christians viewed them with as much hostility as Muslims, an issue that led to a Papal apology in May 2001.[29]

Post-1815, France claimed the Eastern Mediterranean as a 'French lake', a deliberate echo of Napoleon's campaign in Egypt and Syria.[30] In Histoire des croisades, published between 1812 to 1822, Joseph François Michaud depicted the Crusades as an expression of French nationalism. Louis Philippe, installed as king in July 1830, used colonial expansion to bolster support for the new regime. In 1830, France occupied Algiers, then backed Muhammad Ali, ruler of the nominally Ottoman province of Egypt, in his unsuccessful attempt to create an Arab state which included Palestine and Syria.[31]

In 1841, the first of 15 volumes of Recueil des historiens des croisades was published, based on original sources collected by the Maurists prior to the Revolution.[32] Louis-Philippe opened the Salle des Croisades at Versailles in 1843, with over 120 specially commissioned paintings related to the Crusades.[33] The Crusader states were portrayed as proto-French colonies, and France the 'historical protector' of Syriac Christians in Palestine. In 1865, the Melkite Patriarch of Jerusalem published an Arabic translation of an 1840 account of the Crusades by Maxime de Montrond, itself largely based on Michaud. This neutralised terms likely to offend, such as 'barbaric', 'infidel', and 'false prophet; rather than "wars of the Ifranj", or "Franks", they were retitled al-hurub al Salabiyya, or "wars of the Cross".[22]

In the 1820s, British authors like Walter Scott and Charles Mills popularised the cult of Richard the Lionheart, but their focus was Medievalism, with the Crusades as a background. In addition, British policy in Arabia and Palestine was managed from New Delhi, whose main aim was to avoid offending Muslims in British India, Persia, or Afghanistan.[34] When General Allenby led a polyglot Allied army, including Muslims, into Jerusalem in December 1917, he entered on foot, and carefully avoided crusading rhetoric or triumphalism. Unfortunately, the British media was not so sensitive, falsely attributing to Allenby the claim that 'Today, the wars of the crusades are ended'.[35]

At the other extreme, Kaiser Wilhelm II exploited Muslim memories of the Crusades to bolster German political and economic aims with an ostentatious tour of the Levant in 1898. He rode into Jerusalem mounted on a white horse, and visited Damascus, where his wife laid a bronze wreath on the Mausoleum of Saladin. He positioned himself as Saladin's successor, and claimed to be 'Protector of the Faithful', but German efforts to harness Arab nationalism against Britain in 1914-1918 proved incompatible with support for the Ottoman regime.[22]

Modern

.jpg.webp)

In the first half of the 20th century, 'Crusade' was often used to imply a moral objective. Participants in the 1936 Jarrow March against unemployment called themselves 'crusaders', while Eisenhower, Supreme Allied commander, titled his 1948 account of World War II 'Crusade in Europe'. Others used it in its original 'Holy War' form; the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War, and the Mothers' Movement that opposed US involvement in WWII, both described themselves as crusaders against 'Godless communism'.[36]

This provides context to Steven Runciman's three volume A History of the Crusades, published between 1951 to 1954. Rather than being driven by morality or religion, in his judgement the Crusades were 'a long act of intolerance in the name of God.'[37] An historian of the Byzantine Empire, Runciman was appalled by the Fourth Crusade, which colours his perspective.[38] He portrays western Europeans as ignorant, rough and rude, Byzantines as cultivated, sophisticated, and decadent, while Muslims are tolerant, devout, and warlike.[39]

While criticised for these broad stereotypes and other flaws, Runciman's work 'remains the primary standard for comparison'.[40] One reason is the elegance of the writing; Jonathan Riley-Smith quotes Runciman as saying "[he] was not an historian, but a writer of literature". His approach reflected the 19th century concept of a clash of cultures, expanded into the "clash of civilisations", which sees conflict as driven by religious and cultural values, rather than political or economic. Historian Thomas F. Madden states "Runciman single-handedly crafted the current popular concept of the crusades".[41]

In 2001, President Bush described the War on Terror as a 'crusade'. A comment largely unnoticed in the US sparked negative responses in Europe, and among moderate Muslims, for whom it "recalled barbarous and unjust military operations against the Muslim world."[42] The reaction reflects a widespread view within political Islam that the 'Crusader mentality' never went away, as demonstrated by the history of Western intervention in the Middle East.[43] The Crusades thus link directly to modern military and political developments, including the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, the 1948 establishment of Israel, the 1990 Gulf War, or 2003 invasion of Iraq.[44]

Madden suggests this is an artificial construct, derived from the Crusades being used to justify 19th century European colonialism, while in reality they were a mediaeval phenomenon.[45] However, this approach is mirrored by extreme Right-wing elements in Europe and the Americas, who suggest the Christian West once again faces an Islamic threat. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan, or Knights Templar International, commonly employ Crusader symbols, although many are not religious, and consider their domestic political opponents part of the same threat.[46]

Primary Sources

- Recueil des historiens des croisades (ed. 1841–1906) including the twelve surviving chronicles of the First Crusade:[47][48]

- Anonymous, Gesta Francorum (c. 1100)

- Anonymous, Historia belli sacri (c. 1131)

- Albert of Aachen, Historia Ierosolimitana (c. 1120)

- Baldric of Dol, Historia Hierosolymitana (c. 1110)

- Ekkehard of Aura, De oppressione liberatione ac restautatione Jerosolymitanae ecclesiae (c.1125)

- Fulcher of Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana (c 1106)

- Fulcher of Chartres, Gesta Francorum Hierusalem expugnantium (epitome of prev.) (c. 1118)

- Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos (c. 1108)

- Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano itinere (c. 1111)

- Ralph of Caen, Gesta Tancredi (c. 1118)

- Raymond of Aguilers and Pons of Balazun, Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem (c. 1102)

- Robert of Rheims, Historia Hierosolymitana (c. 1107)

- Armenian historians of the crusades include[49]

- Matthew of Edessa (d. 1144)

- Nerses Shnorhali (d. 1173)

- Kirakos Gandzaketsi (d. 1271)

- Nerses of Lambron (d. 1198)

- Sempad the Constable (d. 1276)

- Hayton of Corycus (fl. 1307).

- Muslim historians include[50]

- Ali ibn al-Athir (d. 1233)

- Ibn al-Qalanisi (d. 1160)

- Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad (d. 1234)

- Abd al-Latif (d. 1231)

- Ibn Jubayr (d. 1217)

- Ibn Khallikan (d. 1282)

- Abu al-Feda (d. 1331).

- Contemporary Jewish accounts include[51]

- Solomon bar Simson Chronicle (c. 1140)

- The chronicle of Eliezer bar Nathan (d. 1170)

- The Mainz Anonymous

- The works of Ephraim of Bonn (d. 1200).

References

- Asbridge 2012, p. 40.

- Jones 2020, p. 34.

- Riley-Smith 2009, p. xi.

- Constable 2001, pp. 1–22.

- Tyerman 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Richard 1979, pp. 376-380.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 47–50.

- Lemkin 2012, p. 71.

- Sumption 1999, p. 252.

- Hosking 2012, p. 65.

- Madden 2013, pp. 202-203.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 8–12.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 16–17.

- Tyerman 2011, p. 32.

- Cox 2017, p. 371.

- Reichberg 2017, p. viii.

- Tuchman 1978, p. 25.

- Weinstein 2011, p. 122.

- Murray 2007, p. 36.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 38–40.

- Hopkins 2006, pp. 59-60.

- Phillips 2011.

- Tyerman 2011, p. 79.

- Tyerman 2011, p. 67.

- Tyerman 2011, p. 71.

- Tyerman 2011, p. 87.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 80–86.

- Hillenbrand 1999, p. 5.

- Howard 2001.

- Perry 2019, p. 118.

- Goldschmidt 1988, pp. 16-19.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 142–143.

- Riley-Smith 2008, p. 54.

- Onley 2009, pp. 44-45.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 673–674.

- Jeansonne 2002.

- Tyerman 2006, p. 29.

- Tyerman 2006, p. 560.

- Tyerman 2011, pp. 192–199.

- Vaughan 2007, p. 159.

- Madden 2013, p. 216.

- Ford 2001.

- Ersan 2020, p. 310.

- Asbridge 2012, pp. 674–675.

- Madden 2013, pp. 204–205.

- Koch 2017, p. 1.

- Dass 2011, p. 119.

- Lock 2006, pp. 26–30.

- MacEvitt 2014, pp. 260–275.

- Hillenbrand 1999, pp. 9–30.

- Cohen 2013, pp. 6–7, 31–54, 92–105.

Sources

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Cohen, Jeremy (2013). Sanctifying the name of God: Jewish martyrs and Jewish memories of the First Crusade. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3780-1.

- Constable, Giles (2001). "The Historiography of the Crusades". In Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy P. Mottahedeh (ed.). The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-88402-277-0.

- Cox, Rory (2017). "Expanding the History of the Just War: The Ethics of War in Ancient Egypt". International Studies Quarterly. 61 (2). doi:10.1093/isq/sqx009. hdl:10023/17848.

- Dass, Nirmal (2011). The Deeds of the Franks and Other Jerusalem-Bound Pilgrims: The Earliest Chronicle of the First Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-4422-0497-3.

- Ersan, Mehmet (2020). Hinz, Felix; Meyer-Hamme, Johannes (eds.). A View from Turkey in Controversial Histories – Current Views on the Crusades: Engaging the Crusades, Volume Three. Routledge. ISBN 978-0367148775.

- Ford, Peter (19 September 2001). "Europe cringes at Bush 'crusade' against terrorists". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (1988). Modern Egypt: The Formation Of A Nation-state (2004 ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813338866.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (1999). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0630-6.

- Hopkins, T.C.F. (2006). Confrontation at Lepanto: Christendom vs. Islam. Forge Books. ISBN 978-0-76530-539-8.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A (2012). Russia and the Russians: From Earliest Times to the Present. Penguin. ISBN 978-0718193607.

- Howard, Michael (5 May 2001). "Penitent Pope attempts to end holy war". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Jeansonne, Glen (2002). "An Antiwar Movement That Was Not A Peace Movement: The Mothers' Crusade Against World War II". Peace and Change. doi:10.1111/0149-0508.00108.

- Jones, Dan (2020). Crusaders: An Epic History of the Wars for the Holy Lands. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1781858899.

- Koch, Ariel (2017). "The New Crusaders: Contemporary Extreme Right Symbolism and Rhetoric". Perspectives on Terrorism. 11 (5). ISSN 2334-3745.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2012). Jacobs, Steven Leonard (ed.). Lemkin on Genocide. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-4526-5.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2013). The Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-442-21576-4.

- MacEvitt, Christopher (2014). "True Romans: remembering the crusades among Eastern Christians". Journal of Medieval History. 40 (3). doi:10.1080/03044181.2014.910903.

- Murray, Alan (2007). Housely, Norman (ed.). Kingship, Identity and Name Giving in the family of Baldwin of Bourcq in Knighthoods of Christ: Essays on the History of the Crusades and the Knights Templar. Routledge. ISBN 978-0754655275.

- Onley, James (2009). "The Raj Reconsidered: British India's Informal Empire and Spheres of Influence in Asia and Africa" (PDF). Asian Affairs. XL (1). Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Perry, John (2019). Fichter, James (ed.). A shared sea; Axes of French and British Imperialism in the Mediterranean 1798-1914 in British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: Connected Empires across the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319979632.

- Phillips, John (2011). Before the Kaiser: The Memory of Saladin and the Crusades in the Near East from the Fifteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries (PDF) (PhD). Royal Holloway University. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Reichberg, Gregory (2017). Thomas Aquinas on War and Peace. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107019904.

- Richard, Jean (1979). The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, Volume II. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0444850928.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2009). What Were the Crusades?. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-22069-0.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2008). The crusades, Christianity, and Islam. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-023-1-14624-1.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). The Albigensian Crusade. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571200023.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (2017 ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-0241972977.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02387-0.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2011). The Debate on the Crusades, 1099–2010. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7320-5.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2019). The World of the Crusades. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21739-1.

- Vaughan, Mark K (2007). "God's War: A New History of the Crusades - Review". Naval War College Review. 60 (2).

- Weinstein, Donald (2011). Savonarola The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Prophet. European History Quarterly. 47. doi:10.1177/0265691417711663at.