French conquest of Algeria

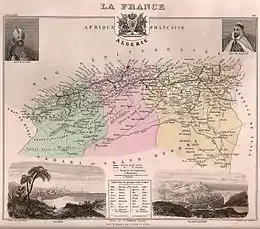

The French conquest of Algeria took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Deylik of Algiers, and the French consul escalated into a naval blockade, following which France invaded and quickly seized Algiers in 1830, and seized other coastal communities. Amid internal political strife in France, decisions were repeatedly taken to retain control of the territory, and additional military forces were brought in over the following years to quell resistance in the interior of the country.

Algerian resistance forces were divided between forces under Ahmed Bey ben Mohamed Chérif at Constantine, primarily in the east, and nationalist forces in Kabylie and the west. Treaties with the nationalists under `Abd al-Qādir enabled the French to first focus on the elimination of the remaining Ottoman threat, achieved with the 1837 capture of Constantine. Abd Al-Qādir continued to give stiff resistance in the west. Finally driven into Morocco in 1842, by large-scale and heavy-handed French military action, he continued to wage a guerrilla war until the Moroccan government, under French diplomatic pressure following its defeat in the First Franco-Moroccan War, drove him out of Morocco. He surrendered to French forces in 1847.

Background information

The territory now known as Algeria was only partially under the Ottoman Empire's control in 1830. The dey ruled the entire Regency of Algiers, but only exercised direct control in and around Algiers, with Beyliks established in a few outlying areas, including Oran and Constantine. The remainder of the territory (including much of the interior), while nominally Ottoman, was effectively under the control of local Berber and a couple of Arab leaders. The dey acted largely independently of the Ottoman Emperor, although he was supported by (or controlled by, depending on historical perspective) Turkish Janissary troops stationed in Algiers. The territory was bordered to the west by the Sultanate of Morocco and to the east by the Ottoman Regency of Tunis. The western border, the Tafna River, was particularly porous since there were shared tribal connections that crossed it.

The Regency of Algiers was one of the main bases of the Barbary pirates and Barbary Slave Traders who attacked Christian ships and coastal settlements in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic. Like the rest of the Barbary Coast, the Regency of Algiers lived from the trade of slaves or goods captured from Europe, America and sub-Saharan Africa. The European powers bombarded Algiers on different occasions in retaliation and the United States provoked the Barbary Wars in order to put an end to Algerian privateering against Christian shipping.[14]

The conquest of Algeria began in the last days of the Bourbon Restoration by Charles X of France. It aimed to put a definite end to Barbary privateering and increase the king's popularity among the French people, particularly in Paris, where many veterans of the Napoleonic Wars lived. Algerian slave trade and piracy immediately ceased after the French conquered Algiers.[15]

Fan Affair

In 1795–96, the French Republic contracted to purchase wheat for the French army from two Jewish merchants in Algiers. The merchants, who had debts to Hussein Dey, the Ottoman ruler of Algiers, claimed inability to pay those debts until France paid its debts to them. The dey unsuccessfully negotiated with Pierre Deval, the French consul, to rectify this situation, and suspected Deval of collaborating with the merchants against him, especially since the French government made no provision to pay the merchants in 1820. Deval's nephew Alexandre, the consul in Bône, further angered the dey by fortifying French storehouses in Bône and La Calle despite prior agreements.[16]

After a contentious meeting on 29 April 1827 in which Deval refused to provide satisfactory answers, the dey struck Deval with his fly-whisk (then called a fan). Charles X used this slight against his diplomatic representative to first demand an apology from the dey, and then to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. The blockade lasted for three years, and was primarily to the detriment of French merchants who were unable to do business with Algiers, while Barbary pirates were still able to evade the blockade. When France in 1829 sent an ambassador to the dey with a proposal for negotiations, he responded with cannon fire directed toward one of the blockading ships. The French then decided that more forceful action was required.[17]

Following the failure of the ambassador's visit, Charles appointed as President Jules, Prince de Polignac, a hardline conservative. This outraged the liberal French opposition, which then had a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. Polignac opened negotiations with Muhammad Ali of Egypt to essentially divide up North Africa. Ali, although nominally a vassal of the Ottomans, eventually rejected this idea. As popular opinion continued to rise against Polignac and the King, they decided that a foreign policy victory such as the capture of Algiers would turn opinion in their favour again.[18]

Invasion of Algiers, war with the regency

Admiral Duperré took command in Toulon of an armada of 600 ships and then headed for Algiers. Following a plan for the invasion of Algeria originally developed under Napoleon in 1808, General de Bourmont then landed 34,000 soldiers 27 kilometres (17 mi) west of Algiers, at Sidi Ferruch, on 14 June 1830. To face the French, the dey sent 7,000 janissaries, 19,000 troops from the beys of Constantine and Oran, and about 17,000 Kabyles.[19] The French established a strong beachhead and pushed toward Algiers, thanks in part to superior artillery and better organization. On 19 June the French defeated the dey's army at the battle of Staouéli, and entered Algiers on 5 July after a three-week campaign.[20] The dey accepted capitulation in exchange for his freedom and the offer to retain possession of his personal wealth. Five days later, he went into exile in Naples with his family. The Turkish Janissaries also quit the territory, leaving for Turkey.[21] The dey's departure ended 313 years of Ottoman rule of the territory.

While the French command had nominally agreed to preserve the liberties, properties, and religious freedoms of the inhabitants, French troops immediately began plundering the city, arresting and killing people for arbitrary reasons, seizing property, and desecrating religious sites. By mid-August, the last remnants of Turkish authority were summarily deported without opportunity to liquidate significant assets.[21] One estimate indicates that more than fifty million francs in assets were diverted into private hands during the plunder.[22] This activity had a profound effect on future relations between the French occupiers and the natives. In 1833 a French commission wrote that "we have sent to their deaths on simple suspicion and without trial people whose guilt was always doubtful ... we massacred people carrying safe conducts ... we have outdone in barbarity the barbarians".[21] The expulsion of the Turks created a power vacuum in significant parts of the territory, from which resistance to French occupation immediately arose.[23]

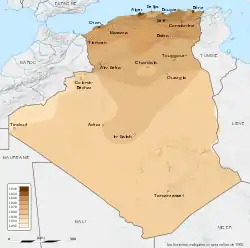

The methods used to establish French hegemony reached genocidal proportions and war, famine and disease led to the death of between 500,000 and 1 million of an estimated 3 million Algerians.[24][25][26]

The news of the capture of Algiers had hardly reached Paris when Charles X was deposed during the Three Glorious Days of July 1830, and his cousin Louis-Philippe, the "citizen king", was named to preside over a constitutional monarchy. The new government, composed of liberal opponents of the Algiers expedition, was reluctant to pursue the conquest begun by the old regime. However, the victory was enormously popular, and the new government of Louis-Philippe only withdrew a portion of the invasion force. General Bourmont, who had sent troops to occupy Bône and Oran, withdrew them from those places with the idea of returning to France to restore Charles to the throne. When it was clear that his troops were not supportive of this effort, he resigned and went into exile in Spain. Louis-Philippe replaced him with Bertrand Clauzel in September 1830.

The bey of Titteri, who had participated in the battle at Staouéli, attempted to coordinate resistance against the French with the beys of Oran and Constantine, but they were unable to agree on leadership. Clauzel in November led a French column of 8,000 to Médéa, Titteri's capital, losing 200 men in skirmishes. After leaving 500 men at Blida he occupied Médéa without resistance, as the bey had retreated.

Colonization begins

Clauzel introduced a formal civil administration in Algiers, and began recruiting zouaves, or native auxiliaries to the French forces, with the goal of establishing a proper colonial presence. He and others formed a company to acquire agricultural land and to subsidize its settlement by European farmers, triggering a land rush. Clauzel recognized the farming potential of the Mitidja Plain and envisioned the production there of cotton on a large scale. During his second term as governor general (1835–36), he used his office to make private investments in land and encouraged army officers and bureaucrats in his administration to do the same. This development created a vested interest among government officials in greater French involvement in Algeria. Commercial interests with influence in the government also began to recognize the prospects for profitable land speculation in expanding the French zone of occupation. Over a ten-year period they created large agricultural tracts, built factories and businesses, and bought cheap local labor.

Clauzel also attempted to extend French influence into Oran and Constantine by negotiating with the bey of Tunis to supply "local" rulers that would operate under French administration. The bey refused, seeing the obvious conflicts inherent in the idea. The French foreign ministry objected to negotiations Clauzel conducted with Morocco over the establishment of a Moroccan bey in Oran, and in early 1831 replaced him with Baron Berthezène.

Berthezène was a weak administrator opposed to colonisation.[27] His worst military failure came when he was called to support the bey at Médéa, whose support for the French and corruption had turned the population there against him. Berthezène led troops to Médéa in June 1831 to extract the bey and the French garrison. On their way back to Algiers they were continually harassed by Kabyle resistance, and driven into a panicked retreat that Berthezène failed to control. French casualties during this retreat were significant (nearly 300), and the victory fanned the flames of resistance, leading to attacks on colonial settlements.[28] The growing colonial financial interests began insisting on a stronger hand, which Louis-Philippe provided in Duke Rovigo at the end of 1831.

Rovigo regained control of Bône and Bougie (present-day Béjaïa), cities that Clauzel had taken and then lost due to resistance by the Kabyle people. He continued policies of colonisation of the land and expropriation of properties. His suppression of resistance in Algiers was brutal, with the military presence extended into its neighborhoods. He was recalled in 1833 due to the overtly violent nature of the repression, and replaced by Baron Voirol. Voirol established French occupation in Oran, and another French general, Louis Alexis Desmichels, was given an independent command that gained control over Arzew and Mostaganem.

On 22 June 1834, France formally annexed the occupied areas of Algeria, which had an estimated Muslim population of about two million, as a military colony. The colony was run by a military governor who had both civilian and military authority, including the power of executive decree. His authority was nominally over an area of "limited occupation" near the coast, but the realities of French colonial expansion beyond those areas ensured continued resistance from the local population. The policy of limited occupation was formally abandoned in 1840 for one of complete control.

Voirol was replaced in 1834 by Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Comte d'Erlon, who became the first governor of the colony, and who was given the task of dealing with the rising threat of `Abd al-Qādir and continuing French failures to subdue Ahmed Bey, Constantine's ruler.

Minor Algerian resistances (1830s)

Blida

In the first battle of Blida, the Berber-Algerian forces led by Mohamed Ben Zaamoum defeated the French army with minimal casualties.

In the Second Battle of Blida, through ambushes, Algerian forces effected a French retreat. Both battles were fought in 1830 and France was only able to capture Blida in 1839.[29]

Béjaïa (Bougie)

Béjaia experienced constant conflicts with the French until its capture. After the fall of the Dey, the tribes of Mézzaïa took over the city. In 1831 they defeated a minor French expedition against them. Nevertheless in 1833 France captured the city with minimal losses, from Kabyle and Kouloughli forces. The Algerian Kabyles tried to recapture the city in 1835, but failed against the better equipped French defenders..[30]

Mitidja

In 1834 the French under the lead of Maximilien Joseph Schauenburg, attacked the city of Hadjout. Resistance used Guerilla tactics against France but was crushed by August 1835.

On 23 February 1837 the French continued their campaign against the Algerian resistance in the Mitidja plains. On 24 February the French met Algerian resistance on the Mitidja plains, and pushed towards the city of Larbaa, which at the time was still under the rule of Algerian tribes. The city was captured two days later.[31]

Zwawas

On 8 May 1837, the Kabyles from the regions of the Col des Beni Aïcha, the Issers and Amraoua raided the Mercier farm of Réghaia under French rule. This motivated the French to start an attack against the Zwawa Kabyles, and the Kabyles of Isser. On the 17 May the French pushed back the Zwawas from Thénia. Meanwhile the French were ambushed by the tribes of Isser and Amraoua, but they were quickly repelled. On 18 and 19 May the French 2nd Light Infantry division defeated a few hundred Algerian defenders at Béni Aïcha. The French lost three soldiers, while the Algerians lost 18. The same day a few hundred Kabyles tried to ambush the French army but were easily defeated by them. The Kabyles suffered considerable losses.[32]

Rise of Abdul Kader

The superior of a religious brotherhood, Muhyi ad Din, who had spent time in Ottoman jails for opposing the bey's rule, launched attacks against the French and their makhzen allies at Oran in 1832. In the same year, tribal elders in the territories near Mascara chose Muhyi ad Din's son, twenty-five-year-old `Abd al-Qādir, to take his place leading the jihad. Abd al-Qādir, who was recognized as Amir al-Muminin (commander of the faithful), quickly gained the support of tribes in the western territories. In 1834 he concluded a treaty with General Desmichels, who was then military commander of the province of Oran. In the treaty, which was reluctantly accepted by the French administration, France recognized Abd al-Qādir as the sovereign of territories in Oran province not under French control, and authorized Abd al-Qādir to send consuls to French-held cities. The treaty did not require Abd al-Qādir to recognize French rule, something glossed over in its French text. Abd al-Qādir used the peace provided by this treaty to widen his influence with tribes throughout western and central Algeria.

While d'Erlon was apparently unaware of the danger posed by Abd al-Qādir's activities, General Camille Alphonse Trézel, then in command at Oran, did see it, and attempted to separate some of the tribes from Abd al-Qādir. When he succeeded in convincing two tribes near Oran to acknowledge French supremacy, Abd al-Qādir dispatched troops to move those tribes to the interior, away from French influence. Trézel countered by marching a column of troops out from Oran to protect the territory of those tribes on 16 June 1835. After exchanging threats, Abd al-Qādir withdrew his consul from Oran and ejected the French consul from Mascara, a de facto declaration of war. The two forces clashed in a bloody but inconclusive engagement near the Sig River. However, when the French, who were short on provisions, began withdrawing toward Arzew, Abd al-Qādir led 20,000 men against the beleaguered column, and in the Battle of Macta routed the force, killing 500 men. The debacle led to the recall of Comte d'Erlon.

General Clausel was appointed a second time to replace d'Erlon. He led an attack against Mascara in December of that year, which Abd al-Qādir, with advance warning, had evacuated. In January 1836 Clausel occupied Tlemcen, and established a garrison there before return to Algiers to plan an attack against Constantine. Abd al-Qādir continued to harry the French at Tlemcen, so additional troops under Thomas Robert Bugeaud, a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars who was experienced in irregular warfare, were sent from Oran to secure control up to the Tafna River and to resupply the garrison. Abd al-Qādir retreated before Bugeaud, but decided to make a stand on the banks of the Sikkak River. On July 6, 1836, Bugeaud decisively defeated al-Qādir in the Battle of Sikkak, losing less than fifty men to more than 1,000 casualties suffered by Abd al-Qādir. The battle was one of the few formal battles al-Qādir engaged in; after this defeat he restricted his actions as much as possible to guerrilla-style attacks.

Constantine

Ahmed Bey had continuously resisted any attempts by the French or others to subjugate Constantine, and continued to play a role in resistance against French rule, in part because he hoped to eventually become the next dey. Clausel and Ahmed had tangled diplomatically over Ahmed's refusal to recognize French authority over Bône, which he considered to still be Ottoman territory, and Clausel decided to move against him. In November 1836 Clausel led 8,700 men into the Constantine beylik, but was repulsed in the Battle of Constantine; the failure led to Clausel's recall. He was replaced by the Comte de Damrémont, who led an expedition which captured Constantine the following year, although he was killed during the siege and replaced by Sylvain Charles, comte Valée.

Abd Al-Qādir's resistance renewed

In May 1837, General Thomas Robert Bugeaud, then in command of Oran, negotiated the Treaty of Tafna with Abd al-Qādir, in which he effectively recognized Abd al-Qādir's control over much of the interior of what is now Algeria. Abd Al-Qādir used the treaty to consolidate his power over tribes throughout the interior, establishing new cities far from French control. He worked to motivate the population under French control to resist by peaceful and military means. Seeking to again face the French, he laid claim under the treaty to territory that included the main route between Algiers and Constantine. When French troops contested this claim in late 1839 by marching through a mountain defile known as the Iron Gates, Abd al-Qādir claimed a breach of the treaty, and renewed calls for jihad. In 1839 he launched the Mitidja Campaign led by the Kabyle commander Ahmed bin Salem, and the Arab Mohammed ben Allel.[33] The campaugn was a success, albeit the Algerian forces were routed in the battle of Oued El Alleug. Throughout 1840 he waged guerrilla war against the French in the provinces of Algiers and Oran. Valée's failures to end the war led to his replacement in December 1840 by General Bugeaud.

Bugeaud instituted a strategy of scorched earth, combined with fast-moving cavalry columns not unlike those used by Abd al-Qādir to progressively take territory from Abd al-Qādir. The troops' tactics were heavy-handed, and the population suffered significantly. Abd Al-Qādir was eventually forced to establish a mobile headquarters that was known as a smala or zmelah. In 1843 French forces raided this camp while he was away from it, capturing more than 5,000 fighters and Abd al-Qādir's warchest.

Abd Al-Qādir was forced to retreat into Morocco, from which he had been receiving some support, especially from tribes in the border areas. When French diplomatic efforts to convince Morocco to expel Abd al-Qādir failed, the French resorted to military means with the First Franco-Moroccan War in 1844 to compel the sultan to change his policy.

France launched a campaign in 1845 in the Kabylia region in hopes of destroying Abdelkader's local forces led by the aforementioned Ahmed bin Salem. The Kabyle Zwawa forces have been a nuisance for France since 1837, and have launched several ambushes such as the Battle of Beni Mered, thus it was Imperative to destroy Abdelkader's forces in the region. After successfully routing Ahmed in the Battle of Tizi Ouzou, the French ambushed the remaining Algerian forces near Issers, successfully destroying the local forces, and causing the surrender of Ahmed bin Salem. This defeat ended Abdelkader's influence in the east of the country.

A French force was destroyed at the Battle of Sidi Brahim in 1845, but eventually hemmed between French and Moroccan troops on the border in December 1847, Abd al-Qādir chose to surrender to the French, under terms that he be allowed to enter exile in the Middle East. The French violated these terms, holding him in France until 1852, when he was allowed to go to Damascus.

The Ottomans lodged a formal protest over the invasion of Algeria, but they never conceded the loss of the province. A map of "Ottoman Africa" from 1905 still shows the empire as possessing a border with Morocco to the west of the "region" (hitta, a term for a territory with vague borders) of Algeria.[34]

1871 Kabyle revolt

The most serious native insurrection since the time of Abd al-Qadir broke out in 1871 in the Kabylie and spread through much of Algeria. By April 1871, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population.[35]

Conquest of the Sahara

.jpg.webp)

The French military expedition, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Flatters, was annihilated by Tuareg attack in 1881.

In 1902, a new French expedition returned, entered Hoggar Mountains and defeated Ahaggar Tuareg in the battle of Tit.

The conquest of the Saharan lands in Algeria finished in 1903 when France conquered the kingdom of Kel Ahaggar. In that regard, the conquest of the entirety of Algeria finished in 1903.

Notes

- "The conquest of the Saharan lands in Algeria finished in 1903 when France conquered the kingdom of Kel Ahaggar. In that regard, the conquest of the entirety of Algeria finished in 1903

References

- Tucker (2009), p. 1154.

- Tucker (2009), p. 1167.

- Taking Power: On the Origins of Third World Revolutions, John Foran p94

- The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987 - Mahfoud Bennoune, p42

- Law, Territory, and the Legal Geography of French Rule in Algeria, p87

- An Economic History of the Middle East and North Africa - Charles Issawi, p211

- The Precarious Balance: State and Society in Africa- Donald S. Rothchild, Naomi H. Chazan - Westview Press, 1988 - 357 pages, p42

- Rothchild, Donald S.; Chazan, Naomi H. (1988). The Precarious Balance: State and Society in Africa. Westview Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-86531-738-3.

- "Urbain states in 1862 that the previous 32 years had killed, at a conservative estimate, over 480,000 people, not just soldiers." The Military and Colonial Destruction of the Roman Landscape of North Africa ... - Michael Greenhalgh, p. 366

- Kamel Kateb, Européens, "indigènes" et juifs en Algérie (1830-1962) : représentations et réalités des populations, INED, 2001, 386 p.

- Diana K. DAVIS, Les mythes environnementaux de la colonisation française au Maghreb, Paris, Editions Champ Vallon, 2007

- Bertrand Taithe, The 1866-1868 Famine in Algeria

- Pour en finir avec la repentance coloniale, Daniel Lefeuvre

- Carver, Robert (25 April 2009). "Not so easy alliances: Two Faiths, One Banner: When Muslims Marched with Christians Across Europe's Battlegrounds". Tablet (Book review). p. 24. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Abun-Nasr (1987), p. 249.

- Abun-Nasr (1987), p. 250.

- Ruedy (2005), p. 47.

- Ruedy (2005), p. 48.

- Ruedy (2005), p. 49.

- Ruedy (2005), p. 50

- Ruedy (2005), p. 52.

- Wagner (1854), p. 235.

- Schaller, Dominik J. (2010). "Genocide and Mass Violence in the 'Heart of Darkness': Africa in the Colonial Period". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- Jalata, Asafa (2016). Phases of Terrorism in the Age of Globalization: From Christopher Columbus to Osama bin Laden. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 92–3. ISBN 978-1-137-55234-1.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 364–ff. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

- Wagner (1854), p. 240.

- Wagner (1854), pp. 241-3.

- Pascal, Adrien; DuCamp, Jules; Brahaut, G N (1850). Histoire de l'armée et de tous les régiments, depuis les premiers temps de la monarchie française... [History of the Army and of All Regiments Since Earliest Times]. 4. François Sicard. Paris: A. Barbier. p. 58. OCLC 1008334451.

- Balzer, Laura (2017). "Des militaires en couple". Hypothèses. 20 (1): 283. doi:10.3917/hyp.161.0283. ISSN 1298-6216.

- Galibert, Léon (1844). L'Algérie: ancienne et moderne depuis les premiers éstablissements des Carthaginois jusqu'à la prise de la Smalah d'Abd-el-Kader (in French). Furne et cie.

- "Tipaza". Tipaza. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "Wayback Machine" (PDF). web.archive.org. 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2021-01-27. Cite uses generic title (help)

- Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü (2010). A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 9–10, 69. ISBN 978-1-4008-2968-2.

- Bernard Droz, « Insurrection de 1871: la révolte de Mokrani », dans Jeannine Verdès-Leroux (dir.), L'Algérie et la France, Paris, Robert Laffont 2009, p. 474-475 ISBN 978-2-221-10946-5

Bibliography

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0.

- Greenhalgh, Michael (2014). The Military and Colonial Destruction of the Roman Landscape of North Africa, 1830-1900. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27163-0.

- Priestley, Herbert Ingram (1966). France Overseas: a Study of Modern Imperialism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-1024-5.

- Ruedy, John Douglas (2005). Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation (2nd ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21782-0.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Wagner, Moritz (1854). The Tricolor on the Atlas: or, Algeria and the French conquest. Translated by Pulszky, Francis. London: T. Nelson and Sons.

.png.webp)