History of Bates College

The history of Bates College began shortly before Bates College's founding on March 16, 1855, in Lewiston, Maine.[note 1] The college was founded by Oren Burbank Cheney and Benjamin Bates.[2] Originating as a Free Will Baptist institution, it has since secularized and established a liberal arts curriculum. After the mysterious 1853 burning of Parsonsfield Seminary, Cheney wanted to create another seminary in a more central part of Maine: Lewiston, a then-booming industrial economy. He met with religious and political leaders in Topsham, to discuss the formation of such a school, recruiting much of the college's first trustees, most notably Ebenezer Knowlton. After a well-received speech by Cheney, the group successfully petitioned the Maine State Legislature to establish the Maine State Seminary. At its founding it was the first coeducational college in New England.[3][4] Soon after it was established, Canadian and American donors stepped forward to finance the seminary, developing the school in an affluent residential district of Lewiston. The college struggled to finance its operations after the financial crisis of 1857, requiring extra capital to remain afloat. Cheney's political activities attracted Benjamin Bates who was interested in fostering his business interests in Maine. Bates donated installments of tens of thousands of dollars to the college to bring it out of the crisis.

The school was renamed "Bates College" in his honor in 1863 and chartered the following year. The college sheltered run-away black slaves illegally and graduated their first African American, Henry Wilkins Chandler, in 1874. The Cobb Divinity School and the Nichols Latin School became affiliated with the college in 1866. Although very few women enrolled at the college in its early days, the first women to graduate from a New England college was Mary Mitchel. In the early 1870s, Bates began its rivalry with Bowdoin College, however this was mainly student-based as many faculty switched between the schools and the college shared trustees on occasion such as Alonzo Garcelon and William Frye. Gridley J.F. Bryant constructed the college's first building, Hathorn Hall. During the American Civil War, Bates played an important role in advocating for the rights of African Americans and women. Many students at the college showed support for the Emancipation Proclamation, and were very vocal members in their respective communities regarding the freedom of African Americans, and general civil rights.

The college went on to send one hundred and seventy-five students to the war, most famously Holman Melcher, Aaron Daggett, and James Porter. After the war, George Colby Chase became the first and only alumnus-president; he went on to establish the Outing Club, dismiss the college's first attempts at establishing secret societies, and created the Brooks Quimby Debate Council. The debate council's international success became linked with the college, contributing to its ensuing national prominence in U.S. higher education. In 1943, the V-12 Navy College Training Program was established seeing the enrollment of Robert F. Kennedy and the naming of a Victory Ship, the S.S. Bates Victory. Bates and Bowdoin joined Colby College to create the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium in 1964; this developed an already budding football and rowing rivalry. In 1970, the college completely secularized and built 22 new academic, residential and athletic facilities, including Pettengill Hall, the Residential Village, and the Bates College Coastal Center at Shortridge. In October 2002, Bates saw its first female president, Elaine Tuttle Hanson, ascend to the presidency to build "The Commons", and guide the college through the 2007-08 financial crisis and subsequent recession. Vice President of Institutional Policy of Harvard University, Clayton Spencer, assumed the presidency in 2012 and led the college into a modern era by instituting new fields of study, breaking fundraising records, building new dorms and launching the $300 million "Bates+You" fundraising campaign.

19th century

Antebellum origins

While attending Parsonsfield Seminary, a Freewill Baptist divinity school, Oren Burbank Cheney lamented the racial segregation and religious oppression that was embedded in American educational institutions. He subsequently sought to create an educational institution that catered to everyone that required it; and that it would take the form of a rigorous and academically prominent school.[5] In 1836, Cheney enrolled in Dartmouth College (after briefly attending Brown), due to Dartmouth's significant support of the abolitionist cause against slavery. Abolitionism would become a foundational aspect of the future Bates College.[6] After graduating, Cheney was ordained a Baptist minister and began to establish himself as an educational and religious scholar.[7]

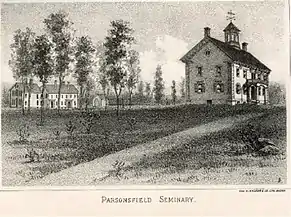

Burning of Parsonsfield

The Parsonsfield Seminary mysteriously burned down in 1853, at midnight. The overall account of the burning remains unclear with sources varying on the actual occurrences. When recounting its burning, Cheney, stated, "the bell tower flickered in flames while the children ran from its pillar-brick walls".[8] The fire was believed to have killed three school children, and two fugitive slaves, leading to a brief and unsuccessful investigation, noted as an act of murder and arson. The reason as to why the Seminary burned down remains unclear, with opponents of abolitionism traditionally, but not definitively, held accountable.[9] News of the burning caused Cheney to advocate for the building of a new seminary in another part of Maine.[10][11]

Maine State Seminary

The "Maine State Seminary" expanded to include liberal arts academics in 1855, making it one of the oldest liberal arts colleges in the United States. Its founding made it the oldest coeducational college in the New England. Cheney met with religious and political leaders in Topsham, Maine, to discuss the formation of a school that catered to Free Will Baptists and was based on principles of egalitarianism, liberty, and scholarship. He began his speech by stating:

We do not propose an Academy [referring to Colby College (then Waterville Academy)], but a school of higher order, between a college [referring to Bowdoin College] and an Academy. We shall petition the state legislature to suitably endow, as well as incorporate, such an institution. We know our claim is good and intend openly and manfully and we trust in a Christian spirit to press it. If we fail next winter, we shall try another legislature. If we fail on a second trial, we shall try a third and a fourth.[9]

The speech was well received and of the one required, twenty-four petitions were submitted to the Maine State Legislature. After minimal delay the charter was approved and appropriated with $15,000 for its conception. With Cheney's influence in the legislature, the Maine State Seminary was chartered on March 16, 1855 and implemented a liberal arts and theological curriculum, making it one of the oldest liberal arts colleges in the United States.

Financial establishment

The campus ran parallel to Frye Street, an area that was part of an affluent residential district of Lewiston.[12] Soon after establishment multiple donors, including members of the Boston elite, stepped forward to finance portions of the school, such as Seth Hathorn, who donated the first library and academic building, which was renamed Hathorn Hall.[13] The college was affected by the financial panic of the later 1850s and required additional capital to stabilize endowment funds.[14] Boston architect, Gridley J.F. Bryant, designed the college's first academic and residential building, Hathorn Hall. The commission was notable as Bryant was the most prominent and most commissioned architect in Boston and usually reserved his skills for the banking and political elite of Boston and abroad. Charging prices considered by many as "ludicrously expensive,"[15] he offered his services at discounted prices for projects that possessed high personal or societal value. He found this trait in the school's advancement of abolitionism, of which he was a proponent. The Hathorn Hall project received high media coverage due to its relative obscurity in comparison with his most prominent projects such as the Massachusetts State House, and select buildings at Harvard College.

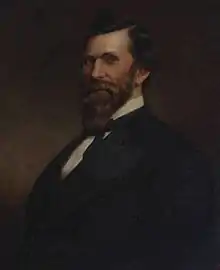

Benjamin Bates

Cheney's impact in Maine was noted by Boston business magnate Benjamin Bates who developed an interest in the college. Bates gave $100,000 in personal donations and overall contributions valued at $250,000 to the college.[16][17] Benjamin Bates suggested to Cheney that the school be located in a more central part of Maine. Their previous business relations lead them to Lewiston Falls. At the time, Lewiston, Maine was one of the most profitable towns in the state and produced large amounts capital for the state and businesses. The school was renamed "Bates College" in his honor on 1863 and was chartered the following year on March 16.[18]

Cheney noted Bates' love for Lewiston and the college, stating:

I have frequently heard him say that he would not knowingly do anything against the interests of the people; and that he would sooner invest ten dollars in Lewiston than one dollar in any other place. 'I love Lewiston', 'I love the College'; he was accustomed to say, 'Say to the Trustees that I love the College.'[19]

Founding date discrepancy

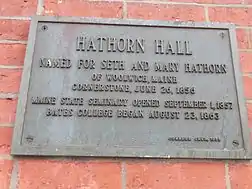

Most sources designate March 16, 1855 as the founding of the Maine State Seminary, which would later go on to be named "Bates College" in 1863.[20][21] Other sources and a plaque on one of the college's buildings–Hathorn Hall–designates September 1, 1857 as the opening of the Maine State Seminary and August 23, 1863 as the opening of Bates College.[22] The official accounts and most sources deem the charter date as its founding date since the Maine State Seminary received its charter from the Maine State Legislature on March 16, 1855.[22] However, since the institution known as "Bates College" also charted, it has another "founding date": March 16, 1864. Through the early and mid 20th century, the official seal of the college designated March 16, 1864 as its founding date usually in the form of: "condita 1864" while others labeled its founding as 1863.[23] This could have been due to the fact that there was growing resistance to seminaries in the area during this time and its founder wanted to separate the college from its founding seminary. In the early 1990s, Bates' president officially changed its founding date to its current one.[23]

Bates' former Cobb Divinity School was founded in Parsonsfield, Maine in 1840 as a graduate school of the Parsonsfield Seminary before moving to Dracut, Massachusetts, then Whitestown, next New York and finally New Hampton, New Hampshire before joining Bates in 1870 as a graduate school. On March 23, 1908 the divinity school merged with Bates religion department, so due to this merger, an 1840 date could also be proposed, since the divinity school was the older institution.[24]

Gaining academic reputation

In 1862, the college graduated Frank Haven Hall, who would later revolutionize modern day computing and typography.[25] Three years later, the college would graduate the first woman to receive a college degree in New England, Mary Mitchel.[26] A small gymnasium was built to house meetings and special sporting events in 1867. One year later as the student body grew, John Bertram Hall was constructed, originally called Lyman Nichols Hall, founder of Lewiston, but renamed to remember John Bertram, a naval captain and donor to the college.[27][28] Bates College already had a reputation for academic rigor and social inclusion and it primarily educated the middle and working classes from Maine.[27][29] The school gained academic prominence through its intellectual focus, including maintaining three literary societies: the Literary Fraternity, Philomathean Society and Ladies' Athenaeum.[30] The seal of the college features a stag deer resting near a pine tree, left of a single of grain, representing the "impact of Maine's nature on the person", a lighted oil lamp representing "unwavering clarity in times of uncertainty", and an open book, representing "academic excellence and devotion."[31][32]

The Cobb Divinity School became affiliated with the college in 1866. Four years later in 1870, Bates sponsored a college preparatory school, called the Nichols Latin School.[33] The college began instruction with a six-person faculty tasked with the teaching of moral philosophy and the classics. Bates' first African American student, Henry Wilkins Chandler, graduated in 1874.[34]

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Bates played an important role in advocating for the rights of African Americans. Many alumni fought or otherwise served in the Civil War. During this time, the Bates Board of Fellows was established. Notable members included U.S. Secretary of State, James Blaine and Governor of Maine, Nelson Dingley.[35] With the commencement of the Civil War, Cheney was stirred and encouraged students to fight in the war as a test of their convictions. His bold and untraditional assertions caused students to question the dynamic involved at the school as this was not a student but the President asserting such unheard of propositions. Many students at the college showed support for the Emancipation Proclamation, and were very vocal members in their respective communities regarding the freedom of African Americans, and general civil rights. The college went on to send one hundred and seventy-five students to the war. One such student was Major Holman Melcher, who enlisted in the 20th Regiment of Maine. His motivations were parallel with that of the typical Bates student and administration.[36] Melcher went on to become a Civil War hero and postbellum mayor of Portland, Maine. He served as a Brevet Major and was a part of the team that charged down Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg.

He was the first person to charge down Little Round Top.[37] The college would also go onto graduate the last surviving Union general of the American Civil War, Aaron Daggett, and James Porter, one of General Custer's eleven officers killed at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Porter has been hailed by numerous historians as a leader that made decisive actions in unclear times. A total of three Bates alumni received the nation's highest military medal, the Medal of Honor.[38] The college's first African American student, Henry Chandler, graduated in 1874.[39] In 1884, the college graduated the first woman to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, Ella Haskell.[40] In 1894, George Colby Chase led Bates to increased national recognition, and the college graduated one of the founding members of the Boston Red Sox, Harry Lord.[41][42]

20th century

1900–1920: Brooks Quimby Debate Council and the outing club

During the Chase presidency, the college's debate team became intercollegiate and associated with the college's academic reputation.[43][44] In 1920, the Bates Outing Club was founded and is one of the oldest collegiate outing clubs in the country, the first at a private college to include both men and women from inception, and one of the few outing clubs that remains entirely student run.[45][46] The debate society of Bates College, the Brooks Quimby Debate Council, became the first college debate team in the United States to compete internationally.[47] In February 1920, the debate team defeated Harvard College during the national debate tournament held at Lewiston City Hall. After this, Bates was established as a dominant force in collegiate debate.[48][49]

In 1921, the college's debate team participated in the first intercontinental collegiate debate in history against the Oxford Union's debate team at the University of Oxford. In 1922, The New York Times called Bates "the power centre of college debating in America."[48] Oxford's first debate in the United States was against Bates in Lewiston, Maine, in September 1923.[49] Also in 1923, U.S. President Calvin Coolidge was given an honorary degree by Bates upon his election to the presidency. In addition, numerous academic buildings were constructed throughout the 1920s.

1940–1960: V-12, RFK, and CBB

During 1943, the V-12 Navy College Training Program was introduced at Bates. Bates maintained a considerable female student body and "did not suffer [lack in student enrollment due to military service involvement] as much as male-only institutions such as Bowdoin and Dartmouth."[47] During the war, a Victory Ship was named the S.S. Bates Victory, after the college.[50] It was during this time that future U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy enrolled along with hundreds of other sailor-students.[51][52][53]

The college began to compete athletically with Colby College, and in 1964, with Bowdoin created the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium. Reynolds began the Chase Regatta in 1988, which features the President's Cup that is contested by Bates, Colby, and Bowdoin annually. All three of the schools compete in the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) and share one of the ten oldest football rivalries in the United States.[54][55] Bates' sports rivalry with the other NESCAC schools dates to the 1870s. Bates and Tufts played the first football game in the state of Maine on November 6, 1875 on a field at the base of Mount David on the Bates campus.[56] Bates and Bowdoin have had a baseball rivalry against each other since at least the 1870s.[57]

1970–1990s: secularization and campus growth

In 1967, President Thomas Hedley Reynolds promoted the idea of teacher-scholars at Bates and secured the construction of numerous academic and recreational buildings.[58] Later that year the college would go on to establish its first formal central administration, headquartered in, and metonymically known as Lane Hall. Most notably, Reynolds was integral to the acquisition of the Bates-Morse Mountain. Under Reynolds, Bates ceased being identified with any particular religion. Although never a sectarian college, Bates has historic ties to the Northern Freewill Baptist denomination whose members were instrumental in its founding. It maintained a nominal link to the Baptist tradition for 115 years. In 1970, that link ended when the college catalog no longer described Bates as a "Christian college."

Bates College contributed to the movement to make standardized testing scores optional for college admission. In 1984, upon the convening of Lane Hall, became one of the first liberal arts colleges to make the SAT and ACT optional in the admission process.[59] In 1989, Donald West Harward became president of Bates and greatly expanded the college's overall infrastructure by building 22 new academic, residential and athletic facilities, including Pettengill Hall, the Residential Village, and the Bates College Coastal Center at Shortridge.[60][61]

21st century

2002–2008: strained ties with Lewiston and campus expansion

Elaine Tuttle Hansen was installed as the seventh and first female president of Bates College on October 26, 2002 in Lewiston, Maine.[62] Amid rising tensions between the Bates community and the city of Lewiston, the college released a message to the city outlining the college's impact in its development and historical significance. In a 2003 memo, Bates noted that the college's operating budget of $65 million, although originating outside of Maine, its expenditure was completely in-state. This accounted for nearly $6 million in direct payments to approximately 360 businesses in the Lewiston and Auburn area, and $1.2 million directly to individuals. It later mentioned that although the college was at the time a tax-exempt organization, it spent $341,000 in fees for services and taxes to the city. Bates cited the impact students and faculty have had on the economy of Lewiston ($70 million in direct spending by faculty, students, and visitors per year), as appropriate and meaningful integration into the community.[63]

Hansen released an internal memo to the Bates community in late March 2003 regarding the U.S. invasion or Iraq,[64] noting the campus protests and the resolution passed by the student government's representative assembly condemning the armed conflict.[65] After Hurricane Katrina, the college suspended tuition requirements for all student affected by its impact in late 2005. She later coordinated with the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities (NAICU) to further financial aid allocation by the college for students in need.[66] In 2005, May 2, was dubbed "Bates College Day" by Governor of Maine, John Baldacci.[67] In late 2007, Hansen announced the construction of 280 Hall, a new residence hall for 150 students at the foot of Mount David.[68] In April 2008, expanded the campus of Bates College by completing the construction of "The Commons" at a cost of approximately $24 million.[69][70]

2007-2012: financial crisis and endowment instability

During the 2007-08 financial crisis and subsequent recession, Hansen released the meeting notes from the October 2008 Board of Trustees meeting. The notes were anticipated by the students as many feared for the economic stability of the college's endowment (i.e. financial aid). In the note, Hansen outlined the current economic climate as being in a period of "declining markets, higher costs of borrowing, the potential impact on giving (i.e. fundraising, endowment spending, etc). Hansen mentioned that the college would have to restructure its 10-year financial model in order accommodate its promise to cover "the demonstrated need of all admitted students." She later commented, "I recognize that these are times of stress and concern for all, but I want you to know that the Trustees and I have every confidence in the strength and perseverance of this institution and the entire Bates community."[71]

In February 2008, a letter was sent to 136 U.S. colleges and universities by the chairman and ranking member of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, Max Baucus and Charles Grassley. The letter proposed mandatory endowment payments and tuition caps for institutions of higher learning that held at or above $500 million in financial endowments. Although Bates, at the time held only $275 million, many students began to refinance loan packages prompting a memo to be issued by the college. Bates noted that although increased financial regulation is surely in the future for Bates, the college will not dismiss loans from its financial aid packages.[72] Bates released a memo outlining fiscal year losses due to the 2007-08 financial crisis and subsequent recession, noting a 31% market value loss. She lowered faculty increases but kept them positive during 2009–10. She announced that there will be no salary or hiring freezes, no layoffs, and that the college "would cover 100% of the increase in health care premiums for families."[73] At the start of February 2011, Hansen renovated Roger Williams Hall and Hedge Hall as a part of "Campus Facilities Master Plan". She released a facilities report later on in the month outlining a "distributed campus plan" by extending the walkways into the city of Lewiston.[74] Hansen announced in the academic year 2011 that she would step down as president.[75] Lane Hall appointed Nancy J. Cable as interim president, to serve through June 30, 2012, while Lane conducted a national search for its eighth president.

2012–present: Spencer era

It was announced soon after that the Vice President of Institutional Policy of Harvard University, Clayton Spencer was to be appointed as her successor.[76] On Friday, Oct. 26, 2012, Spencer assumed the presidency. Her subsequent inauguration speech, "Questions Worth Asking" drew 2,500 students, faculty, alumni, and distinguished members of the American collegiate educational system in Merrill Gymnasium.[77] In February 2016, a gift of $19 million was given to Bates in support of the new academic programs.[78] 1980 alumnus, Michael Bonney and his wife, Alison Grott Bonney gave $10 million, the largest donation by a single party in the history of Bates.[79][80] The central administration also announced the development new areas of study, including a new program resolving around Computer Programing called Computational and Digital Studies.[81] At the start of 2016, the college's central administration, Lane Hall announced the construction of Kalperis Hall and Chu Hall to house students for the 2017 academic year, after a donation of $10 million was made by Michael and Elizabeth Kalperis Chu.[82] In the 2016 fiscal year, the college raised $28.2 million, which broke the 2006 record and marked the third year the college's fundraising has increased by 30 percent annually.[83]

In May 2017, Spencer launched the "Bates + You" fundraising campaign–the largest ever undertaken by the college–totaling $300 million to fund facilities, financial aid, the operational fund, and the endowment. The campaign was met with a $50 million donation from Michael Bonney, and has reached $160 million toward its total goal as of May 2017.[84]

Relationship with Bowdoin

From its inception, Bates served as an alternative to a more traditional and historically conservative Bowdoin College.[85][86] There is a long tradition of rivalry and competitiveness between the two colleges, revolving around socioeconomic class, academic quality, and collegiate athletics.[87][88] During the early years of the life of Bates, students at Bowdoin labeled the college a "school for niggers and women,"[89] and Bates students denounced the elitism present at Bowdoin. During the years between 1860 and 1880, as Bates began to accept more and more black students, Bowdoin resisted[89] which created strained tensions between students as Bowdoin faculty believed that black students "would lose more than they would gain by [attending college]."[89] While Bowdoin had historically been seen as more wealthy and exclusive, Bates established secret societies in 1881, and began to cultivate an environment of elitism similar to Bowdoin's.[90]

Many alumni of Bowdoin subsequently went on to develop Bates during the 1860s and alumni of Bates lectured at Bowdoin. The only institution of higher learning the founder of Bates, Oren Burbank Cheney, oversaw was Bowdoin; he sat as an overseer at the college from 1860 to 1867.[91] Cheney's only son, Horace, went to Bowdoin, and graduated with 100 classmates.[92]

Although Bowdoin graduated its first black student in 1821, campus hostility had the second one graduate in 1864, 43 years later. As Bowdoin's conservative tendencies began to moderate and woman began to be admitted in 1974, the relationship between the two college improved and was consolidated.[89] Bates and Bowdoin would later go on to compete against each other athletically in the 1870s, and subsequently share one of the ten oldest NCAA Division III football rivalries, in the United States.[93][94] Traditions have grown out this rivalry in their respective athletic programs."[94] The taunts between the two colleges at sporting and academic events have grown and adapted in the modern era of the rivalry. The unison chant of "Blowdoin" is ubiquitous at games between the rivals. Historically, Bowdoin has focused on faulting Bates for accepting women and African Americans to their school chanting remarks revolving around racism and sexism,[95] where Bates counter-chanted noting Bowdoin's elitism and racism. Both schools' fans are heard often exchanging the taunt of "safety school", and commenting on their respective college's issues regarding white privilege, cost of tuition, sexual assault, and social elitism.[93]

Connection with Dartmouth

Bates College has long had a nominal connection with Dartmouth in such that the founder of Bates graduated from Dartmouth and felt a "deep connection with the college, and was reported mediating near the grave of Eleazar Wheelock (its founder), on a weekly basis."[9] The connection is reinforced through many parallels including the fact that many buildings were designed after Dartmouth's architectural style and numerous campus distinctions are shared by the two colleges. Boston architect, Gridley J.F. Bryant designed for both of the colleges and enforced design parallels in the two colleges centering around mint green caps and white on brick overlay, switching from Dartmouth green and Bates' garnet. Bates began the second oldest winter carnival in the United States behind Dartmouth. The two colleges also share the distinction of having the smallest endowment and student body of their respective athletic leagues.[94][47]

Due to this the school is often seen as the Little Ivy counterpart to Dartmouth. Students at Bates are also given the opportunity to finish their engineering degrees at Dartmouth culminating in a degree being issued by both of the colleges.[94][47][96][97] Bates students created the Dartmouth Challenge, to make fun of the college's mascot, Keggy the Keg, by spinning parent tradition, Newman Day to new specifications.[88]

Social class and rise of elitism

The college's faculty and students voiced concern over the college's prestige when the first black and female students arrived.[98] The college, under the direction of Cheney, rejected fraternities and sororities on grounds of unwarranted exclusivity.[27][99] However, some secret societies were established in 1881, and served as the primary organ of segregation by socioeconomic status on campus.[90] Select students at the college "desired more aristocratic company" similar to that of Bowdoin College.[90]

Although the egalitarian reputation held during the late 1800s and early 1900s, in the later half, the college's reputation was denounced as elitist. During the late 1940s, it earned a reputation for predominately educating white students who come from upper-middle-class to affluent backgrounds.[100][101][102][103]

In the 1950s the college fenced off the campus in an attempt to "represent boundaries between Bates and Lewiston,"[104] to create a "symbolic separation between the purity of the Academia Batesina and underdeveloped city that surrounded them."[88] The New York Times detailed the atmosphere of the college in the 1960s with the following:

The prestigious Bates College — named for Benjamin Bates, whose riverfront mill on Canal Street in Lewiston was once Maine’s largest employer — provided an antithesis: a leafy oasis of privilege. In the 1960s, it was really difficult for most Bates students to integrate in the community because most of the people spoke French and lived a hard life.[105]

The Bates Student published an article entitled "Debunking the Middle Class Myth", detailing how low income students are “the largest and least visible minorities” at the college and often feel isolated by their more wealthier peers.[106] The college has come under criticism for lack of diversity and socioeconomic homogeneity.[107][103] On April 13, 1994, students protested the Dean of Admissions Office because 90% of the student populate was white and the office made no attempt to rectify the situation. A Chronicle of Higher Education article quoted a student as saying "It's preposterous that a school of this elite stature should have so few minorities."[108]

Minorities at the college, typically classified as non-white and low income students, have noted selected practices and experiences at the college, such as: lack of safe spaces, insensitive professors, tokenism, financial insecurity, indirect racism and social elitism.[101][102][103] In 2011, the college was covered by national news outlets for being the most expensive college in the United States,[109][110][111] which sparked backlash in the Bates community and American academia, citing the statistic as a "signal to the world that Bates is a luxury item" later adding "that is not what higher education is about."

According to a 2017 article on income inequality by The New York Times,[112] 18% of Bates students came from the 1% of the American upper class (families who made about $525,000 or more per year),[113] with "median family income[s] of student[s] at $226,500."[114] One out of seven students at Bates comes from the top 20 percent.[114] In January 2017, the college was reported to be the most expensive college in Maine.[115]

See also

Notes

- There is a discrepancy with the founding of the college.

References

- "September 1857: The Maine State Seminary opens | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "September 1857: The Maine State Seminary opens | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- Larson, Wayde. "Faith By Their Works". Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-12. (Bates: first woman to receive a bachelor's degree in New England in 1869)

- "Bates College". Forbes. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 164.

- Cheney, Cheney, Emeline Stanley Aldrich Burlingame (1907). The Story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Boston, Mass., Pub. for Bates college by the Morning star publishing house. p. 99.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- Chase, Harry. Bates College was named after Mansfield Man. Edmund Muskie Archives: National Resources Trust of Mansfield. p. 5.

- "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Frye Street Historical District".

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- Reed, Roger (2007). Building Victorian Boston: The Architecture of Gridley J.F. Bryant. University of Massachuets. p. 16.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 2.

- Larson, Timothy (2005). Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877,. Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source.

- "Oren B Cheney". Bates College. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 13.

- "A Brief History | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "Enduring Values in a Changing World | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "September 1857: The Maine State Seminary opens | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- "September 1857: The Maine State Seminary opens | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- Anthony, Alfred Williams, Bates College and Its Background, (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1936)

- Maine State Seminary Catalog, 1856-1863

- "Mary W. Mitchell | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- "Chapter 4 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- "A Brief History | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- "A Brief History | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "Brand Identity Guide | Communications | Bates College". Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- Stuan, Thomas (2006). The Architecture of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 23.

In reference to Lane Hall's seal atop its header: "a stag denoting what was commonly referred to as the impact of ones environment, specifically nature, in Maine.. impact of Maine's nature on the person, a single of grain..fruits of ones labour in such an environment" - "An open book, effortlessly situated, restating the college's motto, and fulfilling the notions of academic excellence and devoted study... academic excellence and devotion" - "An oil lamp, representing the college's clear convictions, a moral clarity, in time of uncertain constraints, it lighted the way to a more prosperous time... unwavering clarity in times of uncertainty."

- Nichols Latin School records, Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College. http://abacus.bates.edu/muskie-archives/EADFindingAids/CA0281.html

- "Henry Chandler | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates College". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "Chapter 2 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- Morgan, James. "Who Saves Little Round Top?".

Number four: Col. Chamberlain did not lead the charge. Lt. Holman Melcher was the first officer down the slope.

- "27th Maine - Purged Medal of Honor recipients from 1917 Listed by Company". Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Henry Chandler | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- "Progressive men of the state of Montana". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- "A Brief History | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Harry Lord | Society for American Baseball Research". sabr.org. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- "George C. Chase | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Student Clubs and Organizations | Campus Life | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Bates Outing Club". Bates College. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- "January 1920: The Outing Club's winter birth | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Clark, Charles E. (2005). Bates Through the Years: an Illustrated History. Edmund Muskie Archives: Bates College, Lewiston, Maine. p. 37.

- "Bates debates Harvard at City Hall | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Oxford and Bates to Meet in Debate". Google News Archives. Lewiston Daily Sun. 29 August 1923. p. 14. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Victory Ships by shipyard". www.usmm.org. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- "July 1943: The Navy arrives | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Stuan, Thomas (2006). The Architecture of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 19.

- Walter Isaacson (October 17, 2011). Profiles in Leadership: Historians on the Elusive Quality of Greatness. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780393340761.

- "NESCAC Member Institutions - NESCAC". www.nescac.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- "Bowdoin Football Opens CBB Chase Saturday at Bates - Bowdoin". athletics.bowdoin.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- "Renewed Garcelon Field dedication is Parents & Family Weekend highlight". Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Bates Student 1877, pg. 16, 97 https://books.google.com/books?id=SSIEAAAAYAAJ

- "Thomas Hedley Reynolds | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Optional Testing | Admission | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Donald West Harward | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Donald W. Harward | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Hansen inaugurated as Bates' seventh president | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- "Bates' relationship with the community | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "President Hansen comments on the war in Iraq | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Majority of Bates students oppose pre-emptive military action in Iraq". 2003-02-13. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "President Hansen on Bates' response to Katrina | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Maine Gov. John Baldacci's "Bates College Day" proclamation | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- "280 College Street". 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Lucky Seven: Bates Dining Commons - PUPN Mag". www.pupnmag.com. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- Elbaum, Meredith (2010-05-01). "A Not So Common College Commons: Sustainable Dining at Bates College". Journal of Green Building. 5 (2): 16–26. doi:10.3992/jgb.5.2.16. ISSN 1552-6100.

- "Current Economic climate and Bates | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Financial aid update | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Budget FAQs | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "February 2010 Facilities Update | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Bates president leaving for Johns Hopkins - The Portland Press Herald / Maine Sunday Telegram". The Portland Press Herald / Maine Sunday Telegram. 2011-04-22. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Academic Access, Education Reform". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "'Questions Worth Asking' — President Clayton Spencer's inaugural address | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- Newsroom. "Huge alumni gift for Bates College". www.foxbangor.com. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- Wight, Patty. "Bates to Use $19 Million Donation to Launch Computer Science Program". news.mpbn.net. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Bates announces gifts of $19 million to create six new endowed professorships and launch the college's new digital and computational studies program | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Digital and Computational Studies | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- "Campus Facilities Planning | Bates College". Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- "Giving to Bates soars to record $28.2 million, more than doubling since 2013". 2016-07-28. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- "Bates receives its largest donation ever - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- Calhoun, Charles C (1993). A Small College in Maine. Hubbard Hall, Bowdoin College: Bowdoin College. p. 163.

- Eaton, Mabel (1930). General Catalogue of Bates College and Cobb Divinity School. Coram Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine.: Bates College. pp. 34, 36, 42.

- "Chapter 4 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- Woz, Markus (2002). Traditionally Unconventional. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 6.

- "Chapter 2 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Chapter 4 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- General Catalogue of Bates College and Cobb Divinity School, 1863-1915. The College. 1915.

- New Hampshire State Magazine. H.H. Metcalf. 1901.

- Woz, Markus (2002). Traditionally Unconventional. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 6.

- Nevin, David (1970). Muskie of Maine. Ladd Library, Bates College: Random House, New York. p. 99.

- "Chapter 3 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- Stuan, Thomas (2006). The Architecture of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 23.

- Various. "The Bates Student".

- "Conclusion | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "Top Producers of U.S. Fulbright Scholars and Students". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- "Diversity of what? | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- "Real talk | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- Shawker, Cheri (2016). "White Priviliage at Bates College". Bates College.

- "Is the student-led Mount David cleanup a model for a litter-free hill?". 2016-06-13. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- Araton, Harvey (2015-05-19). "The Night the Ali-Liston Fight Came to Lewiston". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- "Debunking the "Middle Class myth" | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- "The Concerned Students of Color at Bates: A Call to Action | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- "Bates College Students Protest Lack of Minorities". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 1994-04-13. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- Staley, Oliver. "Bates Charging $51,300 Leads Expensive U.S. Colleges List". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- "The 50 most expensive U.S. colleges". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- "Bates College 2014/2015 Statistics and Facts" (PDF). Bates College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-31. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- "Some Colleges Have More Students From the Top 1 Percent Than the Bottom 60. Find Yours". The New York Times. 2017-01-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- Thompson, Derek. "How Much Income Puts You in the 1 Percent if You're 30, 40, or 50?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- Cox, Gregor Aisch, Larry Buchanan, Amanda; Quealy, Kevin (2017-01-18). "Economic diversity and student outcomes at Bates". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- "The most expensive college in every state". Business Insider. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

Further reading

- Alfred, Williams Anthony. Bates College and Its Background. (1936) Online Deposit.

- Stuan, Thomas. The Architecture of Bates College. (2006)

- Chase, Harry. Bates College was named after Mansfield Man. (1878)

- Woz, Markus. Bates College – Traditionally Unconventional. (2002)

- Bates College Archives. Bates College Catalog. (1956–2017). 2017 Catalog.

- Bates College Archives. Maine State Seminary Records. Online Deposit.

- Bates College Archives. Bates College Oral History Project. Online Deposit.

- Clark, Charles E. Bates Through the Years: an Illustrated History. (2005)

- Smith, Dana. Bates College – U. S. Navy V-12 Program Collection. (1943) Online Deposit.

- Eaton, Mabel. General Catalogue of Bates College and Cobb Divinity School. (1930)

- Larson, Timothy. Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College. (2005)

- Calhoun, Charles C. A Small College in Maine. p. 163. (1993)

- Johnnett, R. F. Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. (1878)

- Phillips, F. Charles Bates College in Maine: Enduring Strength and Scholarship. Issue 245. (1952)

- Dormin J. Ettrude, Edith M. Phelps, Julia Emily Johnsen. French Occupation of the Ruhr: Bates College Versus Oxford Union Society of Oxford College. (1923)

- The Bates Student. The Voice of Bates College. (1873–2017)

- Emeline Cheney; Burlingame, Aldrich. The story of the life and work of Oren Burbank Cheney, founder and first president of Bates College. (1907) Online Version.