History of Brown University

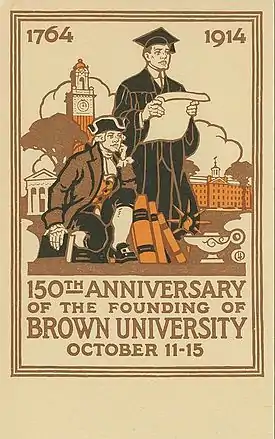

The history of Brown University spans 256 years. Chartered in 1764 as "the College or University in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England, in America," Brown is the seventh oldest institution of higher learning in the United States.[1]

Brown's history is closely related to that of Rhode Island and greater New England.

Establishment

Drafting a charter

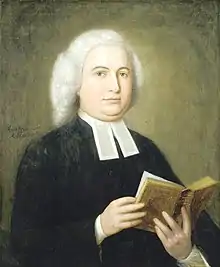

In 1763, The Reverend James Manning, a Baptist minister and an alumnus of the College of New Jersey (predecessor to today's Princeton University), was sent to Rhode Island by the Philadelphia Association of Baptist Churches in order to found a college.[2] Providence Plantations, having been the colony founded by Baptist exile and church founder, Roger Williams in the 1630s. At the same time, local Congregationalists, led by future Yale College president Ezra Stiles, were working toward a similar end. The inaugural board meeting of the Corporation of the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island & Providence Plantations was held in the Old Colony House in Newport, Rhode Island. Former Royal Governors of Rhode Island under King George III Stephen Hopkins and Samuel Ward as well as leading Baptists the Reverend Isaac Backus and the Reverend Samuel Stillman were among those who played an instrumental role in Brown's foundation and later became American revolutionaries. On March 3, 1764, a charter was filed to create the College, reflecting the work of both Stiles and Manning. The university charter was executed under the authority of King George III.

The charter had more than sixty signatories, including the brothers John, Nicholas and Moses of the Brown family, who would later inspire the College's modern name following a gift bestowed by Nicholas Brown, Jr. The college's mission, the charter stated, was to prepare students "for discharging the Offices of Life with usefulness & reputation" by providing instruction "in the Vernacular and Learned Languages, and in the liberal Arts and Sciences."[3] The charter's language has long been interpreted by the university as discouraging the founding of a business school or law school. Brown continues to be one of only two Ivy League colleges with neither a business school nor a law school (the other being Princeton).

The charter required that the makeup of the board of thirty-six trustees include twenty-two Baptists, five Friends, four Congregationalists, and five Church of England members, and by twelve Fellows, of whom eight, including the President, should be Baptists "and the rest indifferently of any or all denominations." It specified that "into this liberal and catholic institution shall never be admitted any religious tests, but on the contrary, all the members hereof shall forever enjoy full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience." One of the Baptist founders, John Gano, had also been the founding minister of the First Baptist Church in the City of New York. The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition remarks that "At the time it was framed the charter was considered extraordinarily liberal" and that "the government has always been largely non-sectarian in spirit."[4] In commemoration of this history, each spring for over two centuries, faculty and the graduating class proceed down the hill, in academic dress, to the grounds of the First Baptist Meeting House (erected in 1774, "for the publick Worship of Almighty GOD and also for holding Commencement in") to publicly confer the bachelor's degree.[5]

Founding

The college was founded as Rhode Island College, on the site of the First Baptist Church at the corner of Main and Miller Streets in Warren, Rhode Island.[6] The first commencement was held in Warren in September 1769.[6] The original church building was burned to the ground by British and Hessian soldiers in 1778, and the present First Baptist Church stands on the original site.[6]

In 1770, the college moved to its present location on College Hill in the East Side of Providence. This move was protested by East Greenwich and Newport, which each argued for their own suitability.[7]

The college was temporarily located on the second floor of the Old Brick Schoolhouse before moving to the College Edifice (now known as University Hall).

James Manning was sworn in as the College's first president in 1765. His tenure ended in 1791.

Funding

At the time of its founding, tuition at Brown was $12 a year. This amount was insufficient to cover the new college's expenses, so its trustees looked to benefactors for funding[7]

In 1766, Rev. Morgan Edwards traveled to Europe to "solicit Benefactions for this Institution." During his year and a half stay in the British Isles, the reverend secured $4,300 in funding. Among the benefactors who contributed to this sum were Thomas Penn and Benjamin Franklin. A similar trip to the American South was later taken by Rev. Hezekiah Smith, who raised an additional $1,700.[7]

The Brown family — Nicholas, John, Joseph and Moses — were instrumental in the college's move to Providence, funding and organizing much of the construction of the new buildings. The family's connection with the college was strong: Joseph Brown became a professor of Physics at the University, and John Brown served as treasurer from 1775 to 1796. In 1804, a year after John Brown's death, the University was renamed Brown University in honor of John's nephew, Nicholas Brown, Jr., who was a member of the class of 1786 and in 1804 contributed $5,000 toward an endowed professorship. In 1904, the John Carter Brown Library was opened as a research center on Americas based on the libraries of John Carter Brown and his son John Nicholas Brown.

The Brown family was involved in various business ventures in Rhode Island, and made a small part of its wealth in businesses related to the slave trade. The family itself was divided on the issue. John Brown had unapologetically defended slavery, while Moses Brown and Nicholas Brown Jr. were fervent abolitionists. In recognition of this history, under President Ruth Simmons, the University established the University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice in 2003.[8]

American Revolution

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp)

Stephen Hopkins, Chief Justice and Royal Governor of the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, was later a Delegate to the Colonial Congress in Albany in 1754 and to the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776. He was a signatory to the United States Declaration of Independence on behalf of the state of Rhode Island. He also served as the first chancellor of Brown (at the time called Rhode Island College) from 1764 to 1785. His house is a minor historical site, located just off the main green at Brown. At the time of his signature of the Declaration of Independence, Stephen Hopkins served as Chief Justice of Rhode Island and Chancellor of Brown.

In 1781, allied American and French armies under the command of General George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau, who led troops sent by King Louis XVI of France, embarked on a 600-mile (970 km) march from Rhode Island to Virginia, where they fought and defeated British forces sent by King George III of the United Kingdom on the Yorktown, Virginia peninsula. The victory ended the major battles of the American Revolutionary War. Prior to the march, Brown University served as an encampment site for French troops, and the College Edifice, now University Hall, was turned into a military hospital.[9]

Other founders of Brown who played significant roles in the American revolutionary effort included John Brown in the Gaspee Affair, Chief Justice Dr. Joshua Babcock as major general in the state militia and William Ellery as a signatory to the Declaration of Independence.

James Mitchell Varnum, who graduated with honors in Brown's first graduating class of 1769, served as one of General George Washington's Continental Army Brigadier Generals and later as Major General in command of the entire Rhode Island militia. David Howell, who graduated with an A.M. in the same year as General Varnum, served as a delegate to the Continental Congress from 1782 to 1785. In 1783, the Comte de Rochambeau and James Mitchell Varnum joined George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and several other distinguished officers as founding members of the Society of the Cincinnati.

Late 18th Century

In 1786, President James Manning served as a delegate for Rhode Island to the Continental Congress.

George Washington visited the college in August of 1790. The newly elected president was accompanied by George Clinton and Thomas Jefferson, among others.[10]

In 1800, enrollment at the college passed 100 students.[11]

19th Century

In September of 1803, the Corporation voted to extend naming rights to the college to any benefactor willing to make a donation of $5,000 within the following year. On September 6, 1804, Nicholas Brown, Jr., class of 1786, donated the sum, prompting the Corporation to rename the college in his honor.[12]

In 1811, Brown began offering lectures in medicine, becoming the third college in New England to do so. Medical study ceased in 1827 under the tenure of President Wayland.[13]

In 1822, the college constructed its second building, Hope College. Construction of the building was funded by Nicholas Brown, who requested that the structure be named for his sister, Hope Brown Ives.[14]

In 1847, Brown established its engineering program, making it the first school in the Ivy League to do so.

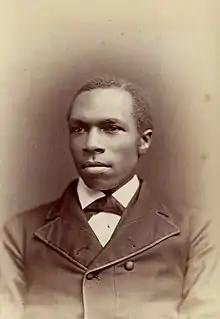

The first African-American students, George W. Milford and Inman E. Page, were admitted in the fall of 1873.

Brown began to admit women when it established a Women's College in Brown University in 1891, which was later named Pembroke College in Brown University. The College of Brown University merged with Pembroke College in 1971 and became co-educational.

The Plastic Age

In 1924, Brown professor Percy Marks published his first novel, The Plastic Age which detailed the decadence and depravity of campus life during the Jazz Age.[15] The novel painted an unflattering picture of partying, boozing, sex, anti-Semitism, and other bad behavior perpetrated by Brown students including S. J. Perelman, who was a student of Marks.[15] In response, the campus humor magazine The Brown Jug (which was edited by Perelman) honored Marks with a banquet.[15]

New curriculum

In 1850, Brown President Francis Wayland wrote: "The various courses should be so arranged that, insofar as practicable, every student might study what he chose, all that he chose, and nothing but what he chose."[16] The adoption of the New Curriculum in 1969, marking a major change in University's institutional history, was a significant step towards realizing President Wayland's vision. The curriculum was the result of a paper written by Ira Magaziner and Elliot Maxwell entitled "Draft of a Working Paper for Education at Brown University."[17] The paper came out of a year-long Group Independent Study Project (GISP) involving 80 students and 15 professors. The group was inspired by student-initiated experimental schools, especially San Francisco State College, and sought ways to improve education for students at Brown. The philosophy they formed sought to "put students at the center of their education" and to "teach students how to think rather than just teaching facts."[18]

The paper made a number of suggestions for improving education at Brown, including a new kind of interdisciplinary freshman course that would introduce new modes of inquiry and bring faculty from different fields together. Their goal was to transform the survey course, which traditionally sought to cover a large amount of basic material, into specialized courses that would introduce the important modes of inquiry used in different disciplines.[19]

Following a student rally in support of reform, President Ray Heffner appointed the Special Committee on Curricular Philosophy with the task of developing specific reforms. These reforms, known as the Maeder Report (after the chair of the committee), were then brought to the faculty for a vote. On May 7, 1969, following a marathon meeting with 260 professors present, the New Curriculum was passed. Its key features included the following:[18]

- Modes of Thought courses aimed at first-year students

- Interdisciplinary University courses

- Students could elect to take any course Satisfactory/No Credit

- Distribution requirements were dropped

- The University simplified grades to ABC/No Credit, eliminating pluses, minuses and D's. Furthermore, "No Credit" would not appear on external transcripts.

Except for the Modes of Thought courses, a key component of the reforms which have been discontinued, these elements of the New Curriculum are still in place.

Additionally, due to the school's proximity and close partnership with the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), Brown students have the opportunity to take up to four courses at RISD and have the credit count towards a Brown degree. Likewise, RISD students can also take courses at Brown. Since the two campuses are effectively adjacent to each other, the two institutions often partner to provide both student bodies with services (such as the local Brown/RISD after-hours and downtown transportation shuttles).[20][21] In July 2007 the two institutions announced the formation of the Brown/RISD Dual Degree Program, which allowed students to pursue an A.B. degree at Brown and a B.F.A. degree at RISD simultaneously, taking five years to complete this course of study. The first students in the new program matriculated in 2008.[22]

As recently as 2006, there has been some debate on reintroducing plus/minus grading to the curriculum. Advocates argue that adding pluses and minuses would reduce grade inflation and allow professors to give more specific grades,[23] while critics say that this plan would have no effect on grade inflation while increasing unnecessary competition among students and violating the principle of the New Curriculum.[24] Ultimately, the addition of pluses and minuses to the grading system was voted down by the College Curriculum Council.[25]

Brown, the Ivy League and slavery

In 2003, 18th Brown University President Ruth J. Simmons appointed the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, which included Brown faculty members, undergraduate and graduate students and University administrators.[26] This Brown Steering Committee produced the first officially endorsed Ivy League report regarding the pre-Revolutionary commercial ties between the origins of one of the Ivy League institutions and the Triangular Trade in slaves taken from various regions in Africa. The Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice is a historic first for the Ivy League, which comprises a few member universities whose officially unexamined initial financial endowments were financed in some measure by wealth accumulated through the Triangular Trade, e.g. benefactor for Yale University Philip Livingston the elder, Yale College alumnus and promoter of then King's College (the former name for Columbia University) Philip Livingston the younger, and benefactor for Harvard University Isaac Royall, Jr.[27] The carefully researched report offers several recommendations for Brown which are addressed in the official University response.[28]

The Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice also offers a wealth of historical records and teaching materials[29] available to the public worldwide regarding an important period in the history of the Ivy League, pre-Revolutionary New England and Triangular Trade contributions to the ascendance of Great Britain's leading universities, including the University of Oxford, University of Bristol and the University of Cambridge, prior to the Slave Trade Act of 1807 passed by the British Parliament. This act of Parliament outlawed the use of British ships in any aspect of the slave trade, in large measure as a consequence of the legislative leadership of Cambridge University alumni William Wilberforce and Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.[30] Wilberforce's work on slavery and justice was depicted in the film Amazing Grace. St. John's College, Cambridge has received funding to conduct inquiries similar to those led by the Brown Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, but naturally focused on the benefits flowing from the Trianglular Trade which accrued to the British Empire and the United Kingdom's most prestigious institutions of learning, including those of Oxbridge.[31] (The endowments bequeathed by Christopher Codrington to create Codrington Library at All Souls College, Oxford are one example of the benefits that flowed from the Triangular Trade involving Rhode Island.[32]) As part of the commemoration of the Bicentenary of the Act of 1807 at Cambridge, President Simmons gave a public lecture at St. John's College entitled Hidden in Plain Sight: Slavery and Justice in Rhode Island.[33]

The records are maintained by the Center for Digital Initiatives at Brown.[34]

As one feature of the official February 2007 Response of Brown University to the Report of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, President Simmons announced Brown's decision to create a U.S.$10 million endowment (£5,043,100.00; €7,400,000.00; ¥1,192,950,000.00) intended to benefit public schools in Providence, Rhode Island in part by funding graduate fellowships in urban education.[35] This initiative echoes recommendations of former Brown president Vartan Gregorian, who suggested in several public addresses that the best remedy for the United States in its efforts to address the legacies of slavery and racial discrimination was to redouble commitments to K-12 education nationally. In that spirit, Dr. Simmons noted: "Lack of access to a good education, particularly for urban schoolchildren, is one of the most pervasive and pernicious social problems of our time. Colleges and universities are uniquely able to improve the quality of urban schools. Brown is committed to undertaking that work."[36]

Memorial

Another part of the Response of Brown University to the Report of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice was the decision to build a memorial "to recognize [Brown's] relationship to the transatlantic trade and the importance of this traffic in the history of Rhode Island." [37] To carry out the task of creating such a memorial, President Simmons appointed the Commission on Memorials in 2007, a 10-member committee of persons affiliated with Brown University and citizens from the Providence and Rhode Island area. This group published a report in 2009, entitled the Report of the Commission on Memorials[38] that outlined its general plan and recommendations for the construction of Brown's Transatlantic Slave Trade Memorial. In this report, the committee listed "several points of importance to the mission and purpose of commemoration projects. These include[d]: capturing the full extent of the history and the present-day implications of that history; addressing the lingering effects of slavery that manifest themselves in disparate social and economic conditions; reflecting the pervasiveness of the trade and its enduring impact; engaging ongoing debate and deliberation about human atrocities; helping people understand where they "fit" in this legacy; opening people's minds to the importance of confronting difficult questions; portraying this history as an American issue, challenge, and opportunity; addressing the ubiquitous nature of such trauma and the need to learn how to recover from such events; connecting to newer groups of immigrants coming into the country; [and] capturing individual stories connected to the legacy of slavery."[38]

In 2014, the university erected a memorial on the Quiet Green to acknowledge the institution's connection to the trans-Atlantic slave trade and memorialize the Africans and African-Americans, both enslaved and free instrumental to the building of the school.[39] The memorial, designed by contemporary sculptor, Martin Puryear, resembles a massive ball and chain, half submerged in the ground.[40]

Brown's response to the Report of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice was published in the year marking the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade by the British Empire in the reign of King George III following a lengthy campaign by the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and the successor Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, as reported by the Oxford Today magazine and presented at Rhodes House in Oxford.[41]

Expansion

In the late 20th and early 21st century, Brown established and re-established three new divisions.

In 1972, Brown re-established its medical school, which had been suspended since 1827. In 2007, the school was renamed the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in honor of benefactor Warren Alpert.[42] In August of 2011, the Alpert Medical School opened a new campus in Providence's Jewelry District. [43]

In 2010, Brown established its division of engineering as a new school of engineering.[44]

In 2013, Brown transitioned the Alpert Medical School's Department of Community Health into an independent school of public health.[45]

Presidents of Brown University

The current president of the University is Christina Hull Paxson. She is the 19th president of Brown University and succeeded Ruth J. Simmons, the first African American president of an Ivy League institution. According to a November 2007 poll by The Brown Daily Herald, Simmons enjoyed a more than 80% approval rating among Brown undergraduates.[46]

See also

- History of Providence, Rhode Island

- History of Rhode Island

- List of Presidents of Brown University

- List of Brown University people

References

- "Brown University | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "Baptist Identity and Christian Higher Education" (PDF). Baptist Identity and Christian Higher Education. Baylor University. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Brunson, Walter C. (1972). The History of Brown University, 1764-1914. p. 500.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 511.

- https://www.brown.edu/web/commencement/2010/content/history.html

- Beebe, Elaine (21 July 2008). "The small-town birthplace of Brown University". Brown University. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Phillips, Janet. Brown University, a Short History (PDF). Brown University Office of Public Affairs and University Relations.

- Howell, Ricardo (2001, July). "Slavery, the Brown Family of Providence and Brown University Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine", Brown University News Service

- "Brown to Commemorate 225th Anniversary of the March to Yorktown". Brown University Office of Media Relations. 2006-05-30.

- "Encyclopedia Brunoniana | Washington, George". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "Brown: A Timeline". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "Encyclopedia Brunoniana | Name". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "Encyclopedia Brunoniana | Medical education". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "Encyclopedia Brunoniana | Hope College". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- "How Percy Marks Got Fired from Brown for Exposing the Depravities of the Ivy League". New England Historical Society. New England Historical Society. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "History of Brown". About Brown. Brown University. Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "The Magaziner-Maxwell Report (Draft of a Working Paper for Education at Brown University)". Open Jar Foundation. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Leubsdorf, Ben (2005-03-02). "The New Curriculum Then". Brown Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Mitchell, Martha (1993). "Curriculum". Encyclopedia Brunoniana. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University Library. ASIN B0006P9F3C. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- "RISD Grad Book 06-07" (PDF). Rhode Island School of Design. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "about safeRIDE". safeRide for Brown + RISD. Brown University. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "Brown and RISD Announce Dual Degree Program" (Press release). Brown University. 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- "Grade Inflation and the Brown Grading System: 2001-2002 Sheridan Center Research Project". The Teaching Exchange. Sheridan Center for Teaching, Brown University. Archived from the original on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Magaziner, Ira; Elliot Maxwell (2006-03-15). "Two Brown alums and architects of the New Curriculum express their skepticism toward plus/minus grading". Brown Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Lutts, Chloe (2006-03-15). "Plus/minus fails key test: Faculty could still vote to change grading system". Brown Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2005-12-11.

- "Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice". Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Brown University. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Zernike, Kate (2001-08-01). "Slave Traders in Yale's Past Fuel Debate on Restitution". nytimes.com/. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Slavery and Justice: Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice" (PDF). Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Brown University. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- A Forgotten History: The Slave Trade and Slavery in New England

- "Parliament and the British Slave Trade 1600-1807". Slavetrade.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-05-13. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- "Cambridge schools commemorate slave trade abolition" (Press release). St. John's College. 2007-02-06. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "History - Slavery and the Building of Britain". BBC. 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Simmons, Ruth (2006-02-16). Hidden in Plain Sight: Slavery and Justice in Rhode Island (Lecture). St. John's College. Archived from the original (MP3) on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "Repository of Historical Documents". Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Brown University. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Brown University (February 2007). "Response of Brown University to the Report of the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice" (PDF). Brown University. Retrieved 2007-12-05. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Brown Announces Commitments to Providence Public Schools" (Press release). Brown University. 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "Report On Slavery and Justice" (PDF). Brown University. October 2006.

- Report of Commission on Memorials, Brown University, March 2009.

- "Dedication of a Slavery Memorial | Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice". www.brown.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Siclen, Bill Van. "In iron and stone, Brown University acknowledges slave ties / Poll". providencejournal.com. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Pinofold, John (July 2006). "We are all brethren". Oxford Today: The University Magazine. Oxford University. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- "History". The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- Abbott, Elizabeth (2011-12-14). "Providence Puts Focus on Making a Home for Knowledge (Published 2011)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- May 28; Lewis 401-863-2476, 2010 Media contact: Richard. "Brown University Establishes School of Engineering". news.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- February 14; Orenstein 401-863-1862, 2013 Media contact: David. "Brown creates School of Public Health". news.brown.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- Liss, Emmy (2007-11-27). "Brown loves Ruth: Approval rating for Simmons sky-high". Brown Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 2013-02-08. Retrieved 2007-12-05.