History of North Omaha, Nebraska

The history of North Omaha, Nebraska includes wildcat banks, ethnic enclaves, race riots and social change spanning over 200 years. With a recorded history that pre-dates the rest of the city, North Omaha has roots back to 1812 with the founding of Fort Lisa. It includes the Mormon settlement of Cutler's Park and Winter Quarters in 1846, a lynching before the turn-of-the-twentieth-century, the thriving 24th Street community of the 1920s, the bustling development of the African-American community through the 1950s, a series of riots in the 1960s, and redevelopment in the late 20th and early 21st century.

Pre-European contact

Bands from the Pawnee, Otoe and Sioux nations were the first to occupy the area around Carter Lake. After a short period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when they were the most powerful Indians on the Great Plains, the Omaha nation settled in the vicinity of present-day East Omaha. After a smallpox epidemic killed much of its population, and encroaching American settlement further reduced their historic way of life, the Omaha sold their lands and moved to their present reservation to the north in Thurston County, Nebraska in 1856.

Mid-19th century

The first settlements in North Omaha were the 1812 Fort Lisa located near Hummel Park and the 1823 Cabanné's Trading Post along the Missouri River. Fort Lisa was built by famed fur trapper Manuel Lisa, a founder of the St. Louis, Missouri Fur Company (later known as the Missouri Fur Company). It was an important fur trading post for securing initial American investment in the Louisiana Territory. Cabanné's Trading Post belonged to John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company, which competed with many traders for the patronage of local Native American tribes. The American Fur Company later bought out Fontenelle's Post, founded by the Missouri Fur Company. Fontenelle's Post became the start of Bellevue, the first town in Nebraska.

Early towns

Founded in August 1846, Cutler's Park was an early tent settlement for pioneers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who were on their way from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City, Utah.[1] Although the Mormons had permission from the US government to occupy land temporarily, Native American tribes argued about whether they should pay a fee or taxes. The Mormons had been putting up hay for the winter from the grasslands.

The disagreement between the Oto and Omaha over the Mormons' use of the land persuaded the pioneers to move that fall three miles (5 km) east to a bluff by the Missouri River where the Oto did not demand a tax. There they created a settlement called the Winter Quarters.[1] Here the Mormons built shelters for the winter: 800 cabins and sod huts. The settlement included a store, bank and town square, and by the spring a gristmill, which became called Florence Mill. The town effectively ceased to exist in 1848, after the entire population had continued their trek west.

In 1854 James C. Mitchell bought the site and founded Florence, which was incorporated two years later. The town was an important stocking point for settlers heading west on the California Trail. The early town included banks, a post office, a large mill, several bars, and other important businesses. Today the Bank of Florence is recognized as the oldest building in Omaha. Brigham Young was believed to have helped build the Florence Mill. Annexed by Omaha in 1917, the community is at the far north end of North Omaha.

South of Florence was a town founded in 1856 for speculators from New York. The Town of Saratoga was located in the proximity of North 24th Street and Ames Avenue. Its economy relied on its connection to the Saratoga Bend on the Missouri River, less than one mile (1.6 km) away. At its peak the town had its own post office, a hotel and several businesses, including its own brewery, along with more than 60 homes. For a few years, it was regarded as being larger than either of its neighboring towns of Omaha City or Florence.

In between Saratoga and Florence was a wide, smooth plain. In the mid-1850s a large group of Irish immigrants built dugouts and sod houses in this area, which other settlers derisively labeled "Gophertown." Residents of Florence and Gophertown skirmished violently in 1856; however, no major change resulted.[2] The Irish became well-established in Omaha, building economic and political power before the waves of European immigrants and black migrants arrived at the end of the 19th century. Many created an ethnic enclave in Sheelytown in South Omaha, near work at the stockyards and meatpacking plants.

Scriptown was an area of North Omaha bound by 16th street on the east, 24th on the west, and Lake Street to the north. It was originally platted in 1855 to provide land to Nebraska Territory legislators who voted for Nebraska statehood. Consequently, the area was developed quickly, and included a number of prominent homes.[3] From its development following the Scriptown platting, North Omaha was the dominion of a mixed European immigrant community that mingled extensively with the African-American community that grew around the start of the 20th century. The Jewish community in the area was rich, with several synagogues the provided social and cultural activities. The B'nai Jacob Synagogue was located at North 25th and Nicholas Streets; the B'nai Israel Synagogue was at North 18th and Chicago Streets; and the Adass Yeshuren Synagogue was at North 25th and Seward Streets. There are several Jewish cemeteries in the area as well.[4]

Other early communities in the area included Casey's Row, an early community of housing for African-American families, most of whose men were employed as porters at the Union Pacific railyards to the east.[5] Squatter's Row was another residential area, located between North 11th and North 13th Streets, from Nicholas to Locust Streets, behind the Storz Brewery. For more than 75 years this area was inhabited solely by squatters.[6]

Late 19th century

The rest of the area comprising modern-day North Omaha developed in spurts. The Near North Side, closest to downtown, developed quickly in this period with many homes for working-class European immigrant and African American families.

Early businesses and housing were propelled by the introduction of a horse-driven street railroad in the 1870s, and electrical streetcar lines operated in North Omaha until 1955.[7] Many early businesses in North Omaha were established by Jewish immigrants,[8] who became part of the larger community of successful business people who built downtown Omaha.

In 1875, the Omaha Driving Park Association purchased a parcel of land located between Laird and Boyd Streets, and 16th to 20th Streets for horse racing, specifically, trotters. A fair association leased it, added some features, and held the Douglas County Fair and the Nebraska State Fair there for many years. The park fell into disuse by 1899; there is a report that this area was re-opened as Sunset Driving Park in 1904.[9]

During this period early Omaha banker Herman Kountze owned a large parcel of land in North Omaha, which he platted as a subdivision called Kountze Place. On May 17, 1883, Buffalo Bill founded his famous Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition in that area, making its first appearance at the aforementioned Omaha Driving Park.[10] More than 8,000 people attended the first exhibition at a location near 18th and Sprague Streets. Buffalo Bill's Wild West show later returned to North Omaha for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1898.[11] Held in conjunction with the Expo, the Indian Congress drew more than 500 American Indians representing 35 tribes to the area, as well.

Kountze Place developed after the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, with developments including large homes and several mansions built around the Expo's only remnant, Kountze Park. Lake Nakoma, now known as Carter Lake, was a hotbed of local sporting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The lake and surrounding park featured sailing events, rowing clubs, Bungalow City, and the Omaha Gun Club.[12] Miller Park was an early site for golfing and boating, and Kountze Park featured several outdoor activities, as well.

Also in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many European Jewish immigrants became involved in the Progressive and socialist movements. Some later became labor organizers in the meatpacking industry, which after two efforts, finally organized in the late 1930s and early 40s.

Catholic parishes grew extensively with new Irish and German immigrant families.[13] The importance of several arterial streets was confirmed in a prominent business journal in 1890, that noted, "North Sixteenth, Cuming and North Twenty-fourth streets on the north and northwest are... prominent business streets, radiating from the commercial center into the resident portions of the city."[14] Activities in North Omaha, particularly the locating of the Nebraska State Fair at the Omaha Driving Park, led to the formation of the civic and business association Ak-Sar-Ben in 1895.[15]

20th century

North Omaha has suffered in severe Plains weather. In 1902 a major early spring storm demolished a lot of the neighborhood in the Monmouth Park neighborhood. The tornado-like activity destroyed the original Immanuel Hospital and closed North Omaha's Franklin School.[16] The most significant weather-related event to hit Omaha was the Easter Sunday tornado of 1913 that destroyed many of the area's businesses and neighborhoods. It cut a path of destruction through the city that was seven miles (11 km) long and a quarter of a mile wide. In the city as a whole, 140 people died and 400 were injured. Twenty-three hundred people were homeless; with 800 houses destroyed and 2000 damaged. [17] In the 1913 Easter Sunday Tornado, the Idlewild Pool Hall at 2307 North 24th Street was the scene of the greatest loss of life. The owner, C. W. Dillard, and 13 customers were killed as they tried to take shelter on the south side of the pool hall's basement. The victims were crushed by falling debris or overcome by smoke from fires begun when wood stoves used for heating overturned. North 24th Street was laid waste. The victims were removed to the Webster Telephone Exchange Building.[18] The building was a central headquarters as the community recovered. Operators went to work despite the building missing all of its windows.[19]

Starting with the development of the Minne Lusa neighborhood, in the 1910s the area near Florence became home to an almost exclusively Danish immigrant community. With a variety of churches and social clubs, the neighborhood was the cultural center for many of North Omaha's working class and middle-class whites. The North Omaha Business Men's Association made numerous contributions to Omaha commerce, culture, and education. The group was responsible for developing a new athletic field at Omaha University in 1928.[20]

Recruited for jobs by the meatpacking industry, African American migrants doubled their population in Omaha between 1910 and 1920, with a population among western cities second only to Los Angeles. By the late 19th century, the community already had three churches, which contributed much to its life. The African-American community culture in North Omaha developed a musical legacy of blues and jazz through the 1950s. In 1938 Mildred Brown and her husband founded the Omaha Star newspaper, since 1945 the only black paper in the state. Brown kept it going by herself for more than 40 years until her death in 1989. Since her death, her niece took it over.

In the 1930s and 40s, the black community together with white labor organizing partners worked against the segregated practices of the meatpacking plants. Through their organizing the interracial United Packinghouse Workers of America, part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), they began to win concessions from management. The UPWA was integrated and progressive, also supporting integration of public facilities in Omaha, and the larger Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

From the early 1930s through the 1950s, the Reed Ice Cream Company operated 63 small "ice cream bungalows" that distributed their ice cream across Omaha, including dozens in this neighborhood. One of the bungalows was located 620 N. 40th Street. Co-founded in 1929 by Claude Reed, and his business partner Christian F. Becker, the company plant was located at 3106 N 24th Street. The company sold ice cream in Omaha and Council Bluffs, with a volume of up to 22,000 cones a day. By 1955 there were a few commercial buildings along Ames Avenue and North 30th Street. Two businesses along North 30th Street included the Wax Paper Products Company and the Independent Biscuit Company.[21]

Restructuring of the railroad and meatpacking industries resulted in massive job losses, more than 10,000, for working-class people in Omaha. Changes started to affect the neighborhood in the late 1960s. Families who remained became more poor and the area became predominantly black. Demographics have continued to change, but the city's improving economy has allowed reinvestment in the community. Other businesses in North Omaha included the Vercruysse Dairy, located on the southwest corner of North 52nd Street and Ames Avenue, the Omaha Safe Deposit and Trust Company, and the J.F. Smith Brickyard located on North 30th Street.

Other historically significant businesses included the Storz Brewery, which was located at the corners of Sherman Avenue (also called 16th Street) and Clark Street and finished in 1894. The Storz Brewery was 600 feet (180 m) tall and had a capacity of 150,000 barrels a year, making it one of the largest breweries in the region. The entire facility occupied more than 15 buildings with red-tiled floors and walls, burnished stainless steel and copper fixtures.[22] The Minne Lusa Theater was a one-screen neighborhood movie house that opened in the mid-1930s along North 30th Street that seated 400.[23]

In the 1940s, North Omaha was the home to the African-American players of the Omaha Rockets independent baseball team. The team played exhibition games against Negro league teams from across the U.S. It had several important players.[24][25]

In 1947 a total of 15,000 people worked in the meatpacking industry in Omaha. By 1957, fully half the city's workforce worked in the meatpacking industry. In the 1950s, the United Packinghouse Workers used their economic and political strength to demand that Omaha's bars, restaurants, and other establishments halt segregationist restrictions. As the packing industry changed in the 1960s and moved operations closer to the meat producers, Omaha lost 10,000 jobs. This meant a loss of political power as well for African Americans and other working-class people. Although new meat packers have opened some new operations in Omaha, unionization has dropped sharply in the two decades after 1980, and African Americans have gained few of the new jobs.[26]

Historical residences

North Omaha's earliest homes were built in the Florence area soon after Winter Quarters were disassembled. Its first identification as a distinct bedroom suburb of Omaha occurred in the early 1870s, when professionals who worked in downtown Omaha built their homes a mile north of downtown Omaha,.[27][28] For many years it was home to several prominent Omaha families, businesses, and organizations,[29] and in 1887 North Omaha was annexed to the city of Omaha.[10] Early north Omaha residential developments were mostly occupied by European immigrants from Ireland and Eastern Europe, as evidenced by the construction of the churches where they worshiped, such as Holy Family Church on North 18th and Izard Streets.[30]

West Central-Cathedral Landmark Heritage District developed around the Academy of the Sacred Heart, opened in 1882, and St. Cecilia Cathedral. This primarily residential district, the heart of which lies along both sides of North 38th Street, is the northern portion of what is known as the Gold Coast.[31]

The area of far North Omaha from Ames Avenue north was not commonly acknowledged as an incorporated part of the city until after World War II, when a housing boom filled in many communities throughout the area[32]

North Omaha was the site of several federal housing projects, first built in the 1930s as no-cost or low-cost housing for working-class families, often of Eastern European descent. Because of job losses and population changes in the city, by the late 1960s the projects in North Omaha were inhabited almost entirely by poor and low-income African Americans.

Because of problems with crime, maintenance and segregation, as well as changing ideas about housing, in the early 2000s, the city tore down these facilities, including the Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects. They replaced them with other public housing schemes featuring mixed-income and uses, with more community amenities.

Racism in housing

After the 1919 Omaha Race Riot, landlords began enforcing race-restrictive covenants. Properties for rent and sale were restricted on the basis of race, with the primary intent of keeping North Omaha "black" and the rest of the city "white." Redlining by banks in decisions about loans supported such restrictions and limited reinvestment in North Omaha.[33] The federal government's effort to insure mortgage lending led to racial discrimination in awards of loans. Such restrictions were ruled illegal in 1940.

Boyd and Taylor Streets and North 30th Street between Manderson and Bedford are reported to have developed in the 1920s. Harry Buford was a well-to-do member of North Omaha's African-American community with a large home built in 1929 at 1804 North 30th Street. According to one report, "The location of the family home on the west side of North 30th Street indicated the status of the Buford family in Omaha during a period of racial segregation."[34] These types of differentiations according to socioeconomic and racial boundaries were prevalent throughout the North Omaha area, as in other communities across the country.

In an effort to improve working class housing in North Omaha during the Depression, in the 1930s the Federal government built the Logan-Fontenelle projects, which housed up to 2100 people in 556 apartments. The development was similar to a project of public housing on the South Side of Omaha. Every street was landscaped with trees. The project was named after a leader of the Omaha nation.

Originally the housing was intended to be temporary, for working people with families. It was a significant improvement over housing then available to them. With later losses of jobs in Omaha, more people who were unemployed lived in the projects. Logan Fontenelle became heavily segregated as well and suffered from a concentration of poor families with difficulties.

Racial tension

Omaha's African-American residents were spread throughout the small city from its founding through the 1900s. In 1891 a white mob lynched an African-American man named George Smith.[35] However, in the first few decades of the new century, increasing numbers of immigrants and migrants, and competition for jobs and housing, prompted eruptions of racial violence. Many African Americans had first been recruited by the meatpacking industry as strikebreakers, which raised resentment against them by working class ethnic immigrants and their descendants.

In 1919, after Red Summer, a time of racial riots in several major industrial cities, a mostly ethnic immigrant white mob from South Omaha terrorized the city's African-American population. They began by dragging Will Brown from his jail cell. He was beaten and lynched. After the mob was done with Brown's corpse, they attacked property and other African Americans in Omaha. Their efforts were thwarted, however, by the arrival of soldiers from Fort Omaha who created a boundary around African-American neighborhoods to protect them. The commander also stationed troops in South Omaha to prevent any more mobs from forming.[36]

Riots, including arson and significant property damage, skirmishes with local police, and a bombing in the mid- to late-20th century were demonstrations of other racial tensions. The area continues to be somewhat racially charged, as it remains largely composed of poor African-American constituents, and violent crime is still higher than in other areas of the city. However, it has not experienced any major race incidents since 1993.[35]

Historical architecture

Early North Omaha buildings and homes were characterized by their modest purposes. An example of such simplicity is located in the four-square-style houses located at N 38th Street and Glenwood Avenue. Craftsman and Craftsman-style bungalows were also popular in more affluent areas.[37] According to one report, "many neighborhoods generally consist of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century vernacular and period revival style houses, commercial, educational, and religious resources, and concentrations of post-World War II housing and public housing."[38]

Due to its exceptionally diverse history, particularly in respect to the rest of Nebraska, North Omaha is home to numerous historical and modern landmarks, listed on the Registered Historic Places within its boundaries.

Historical government

Historical transportation

An early horse-drawn coach ran from Florence to Saratoga into Omaha from the 1860s through 1890s. Around that time horse-drawn trolleys replaced these coaches, which were then replaced with electrical street cars. North Omaha was the location of at least four street car lines that ran along 16th, 20th, 24th and 30th Streets, north and south from downtown Omaha.

There were several railroad tracks in North Omaha, including those along Sorenson Parkway and parallel to 24th Street.[39] The Webster Street Depot was located at 15th and Webster Streets, and the Florence Depot was on North 30th Street in Florence.

From at least before 1926, Nebraska Highway 5 used to run down N. 20th Street, jogging east on Ohio Street, and then along 16th. By 1931 this was replaced by N. 30th Street, which was designated as US 73. In 1984 US 73 was replaced by US 75, which maintains its position along N. 30th Street today.[40] Between 1978 and 1980 a new freeway was built from I-480 north to Lake St, called I-580. This status was revoked when the State of Nebraska refused to upgrade the roadway to Interstate specifications, and the roadway is currently called the North Omaha Freeway.

Historical military presence

In 1878 Fort Omaha became the Headquarters for the Department of the Platte, covering territory that stretched from the Missouri River into Montana and from Canada to Texas. It was a supply fort, rather than a defense fort, that provided assistance for the American Indian Wars, World War I, and World War II. Fort Omaha is best known for its role in the 1879 landmark trial of Ponca chief Standing Bear. Originally known as Omaha Barracks, the frame buildings of the post surrounded and faced a rectangular parade ground. On the level ground on the east side were the post headquarters, guardhouse, bakery, storehouses and sutlers store. Ten single-story barracks were constructed to accommodate an equal number of companies, ten being the number of companies which then comprised a regiment. Five of the barracks were on the north end of the parade ground and the other five on the south end.[41] The hospital was built northwest of the north barracks. Most of these buildings still stand at the intersections of 30th and Fort Streets.

The Fort Omaha Balloon School was the first such military school in America, and was located in North Omaha. After the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, operations increased to the extent that a sub-post was needed to accommodate men and the maneuvering balloons. "Florence Field," about a mile north of the fort, consisting of 119 acres (0.48 km2), was acquired for this purpose.[42]

The troops at Fort Omaha were responsible for restoring order to the city after the Omaha Race Riot of 1919.

Libraries

In 1921 the city opened the North Branch Church Library at 25th and Ames. The location has been moved twice since, and the library has been renamed the Charles B. Washington Branch.[43]

Political and Civil rights movements in North Omaha

North Omaha ace of political activism, especially by the Jewish American and African-American communities. They worked together in labor organizing, succeeding with the Meatpacking Union in the 1930s and 1940s.

Starting in the 1920s the community was home to both national and local organizations seeking equal rights for African Americans, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League. The De Porres Club met there starting in the late 1940s. During the 1960s popular locations in North Omaha for community activists to gather included the Fair Deal Cafe on 24th Street and Goodwin's Spencer Street Barbershop at 3116 N. 24th Street, where young Ernie Chambers was a barber. The movement continues to be represented by Senator Chambers, and continues in the community today.

Notable figures from North Omaha

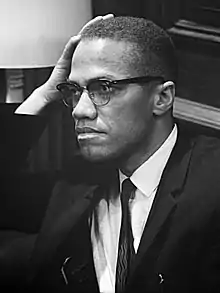

North Omaha has been the birthplace and home of many figures of national and local import. They include Malcolm X; Whitney Young, an important civil rights leader; the storied Nebraska State Senator Ernie Chambers, and author Tillie Olsen.

Singer Wynonie Harris, saxophonist Preston Love and Buddy Miles all have called North Omaha home. Businesswoman Cathy Hughes is from North Omaha. The community has also had several sports stars, including baseball player Bob Gibson, football player Johnny Rodgers, actress Gabrielle Union, actor John Beasley, Houston Texans running back Ahman Green, and basketball player Bob Boozer.

See also

- North Omaha, Nebraska

- Timeline of North Omaha, Nebraska history

- Landmarks in North Omaha, Nebraska

- Timeline of Racial Tension in Omaha, Nebraska

- List of articles related to North Omaha, Nebraska

Bibliography

- Unknown. (1987) Boom and Bust on the Frontier: North Omaha's Story. Omaha Public Library.

- Bish, James D. (1989) The Black Experience in Selected Nebraska Counties, 1854-1920. M.A. Thesis, University of Nebraska at Omaha.

- (n.d) History of North High School

- Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. (1984) Patterns on the Landscape, Heritage Conservation in North Omaha. City of Omaha Planning Department.

- A Time for Burning, 60 minutes, VHS/DVD. A 1966 award-winning documentary about race relations in Omaha. Features State Sen. Ernie Chambers as a young man.

- A Street of Dreams, 58 minutes, VHS. Great Plains National Instructional TV 1994. Documents the history of North Omaha's African American and Jewish community on North 24th Street, which flourished in the 1920s.

- (2005) A Rich Music History Long Untold, The Omaha Reader. - Describes Omaha's influence on many genres of music, including jazz, blues, soul, R&B, and rock.

- Mihelich, Dennis. (1979) "World War II and the Transformation of the Omaha Urban League", Nebraska History 60(3) (Fall 1979):401-423.

- Paz, D.G. (1988) "John Albert Williams and Black Journalism in Omaha, 1895-1929." Midwest Review 10: 14–32.

- (2003) The Negroes of Nebraska: The Negro Comes to Nebraska. CFC Productions.

- Wilhite, A. (1970) The Saratoga Story, Inflated Beginnings. - Omaha History Society

- Finlayson, A.J. (1978) The Mysterious Disappearance of Saratoga.

References

- Gail Holmes, "Early Latter-day Saints - Settlement Cutler's Park", Early LDS, Sep 2006, accessed 2 Sep 2008

- Bristow, D. (2002) A Dirty, Wicked Town: Omaha in the 19th Century. Caxton Press.

- (n.d.)"Andreas' History of Nebraska: Douglas County".

- (1948) Checker Cab Directory. p. 26. Retrieved 8/4/07.

- (1981) "Project Prospect: A youth investigation of blacks buried at Prospect Cemetery" Girls Club of Omaha

- Federal Writers Project. (1939) Nebraska: A guide to the Cornhusker state Nebraska State Historical Society. p 243.

- (n.d.) Transportation Page Archived 2007-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Omaha Exchange

- Olsen, T. (1995) Tell Me a Riddle (Women Writers : Texts and Contexts) Rutgers University Press.

- (n.d.) Omaha Driving Park Track Info The GEL Motorsport Information Page.

- (n.d.) Omaha Timeline 1880-1889 Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Douglas County Historical Society

- (n.d.)Buffalo Bill at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition and Indian Congress of 1898. Nebraska State Historical Society.

- Historical postcard from the Omaha Gun Club

- Street of Dreams Nebraska Public Television

- (1890) Nebraska State Gazetteer Business Directory & Farmer's List Archived 2007-01-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- (n.d.)"History of Ak-Sar-Ben" Archived 2007-03-21 at the Wayback Machine, Ak-Sar-Ben

- "Big storm at Omaha," New York Times. March 12, 1902. Retrieved 1/18/08.

- Sing, T (2003) Omaha's Easter Tornado of 1913. Arcadia Publishing.

- (n.d.)1913 Easter Sunday Tornado Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Omaha Public Library

- (n.d.)Omaha's Terrible Evening. Tragic Story of America's Greatest Disaster.

- (n.d.) Football University of Nebraska at Omaha Alumni Association

- Reconnaissance Survey of Select Nebraska Communities

- Storz Brewery History Archived 2006-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- (nd) Minne Lusa Theater. Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 6/11/07.

- (n.d.) Mickey Stubblefield Profile

- (n.d.) Barnstorming & Tournament Ball Archived 2006-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- [Bacon, David (2005) "And the Winner Is... Immigration reform on the killing room floor" The American Prospect.23 Oct 2005] Accessed 11.10.05

- (n.d.) Art Work of Omaha - 32nd Street, 39th Street Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- (n.d.) Yates Residence Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- (n.d.) Historic Families Archived 2007-02-06 at the Wayback Machine Douglas County Historical Society

- (n.d.) Holy Family Church City of Omaha Landmarks Heritage Preservation Commission. - The church, built by Irish immigrants, is located at 915 North 18th Street.

- West Central-Cathedral Landmark Heritage District City of Omaha.

- (1937) Omaha Plat Map

- (1992) A Street of Dreams. Nebraska ETV Network (video)

- "Reconnaissance Survey of Select Nebraska Communities"

- Bristow, D. (2002) A Dirty, Wicked Town: Tale of 19th Century Omaha. Caxton Press.

- A Street of Dreams Nebraska Public Television.

- Mead and Hunt, Inc. (2003) Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Neighborhoods in Central Omaha. Prepared for the City of Omaha.

- Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Neighborhoods in Nebraska

- (1948) Checker Cab Directory. p. 56. Retrieved 8/4/07.

- Morrison, J. (2007). Council Bluffs/Omaha: Highway Chronology Archived 2006-06-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- (n.d.) Omaha Military History Archived 2007-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Reeves, R. (n.d.) Douglas County History University of Nebraska.

- (n.d.) North Branch Library Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Omaha Public Library.

External links

- NorthOmahaHistory.com - Articles featuring people, places and events from the history of North Omaha by Adam Fletcher Sasse

- BlackPast.org - A website featuring much history from North Omaha

- Historical Florence website