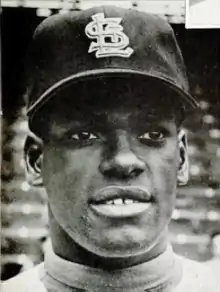

Bob Gibson

Robert Gibson (born Pack Robert Gibson; November 9, 1935 – October 2, 2020) was an American professional baseball pitcher who played 17 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the St. Louis Cardinals (1959–1975). Nicknamed "Gibby" and "Hoot" (after actor Hoot Gibson), Gibson tallied 251 wins, 3,117 strikeouts, and a 2.91 earned run average (ERA) during his career. A nine-time All-Star and two-time World Series champion, he won two Cy Young Awards and the 1968 National League (NL) Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award. Known for a fiercely competitive nature and for intimidating opposing batters, he was elected in 1981 to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. The Cardinals retired his uniform number 45 in September 1975 and inducted him into the team Hall of Fame in 2014.

| Bob Gibson | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Gibson at Roger Dean Stadium in 2010 | |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: November 9, 1935 Omaha, Nebraska | |||

| Died: October 2, 2020 (aged 84) Omaha, Nebraska | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| April 15, 1959, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 3, 1975, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 251–174 | ||

| Earned run average | 2.91 | ||

| Strikeouts | 3,117 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1981 | ||

| Vote | 84.0% (first ballot) | ||

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Gibson overcame childhood illness to excel in youth sports, particularly basketball and baseball. After briefly playing under contract to both the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team and the St. Louis Cardinals organization, Gibson decided to continue playing only baseball professionally. He became a full-time starting pitcher in July 1961 and earned his first All-Star appearance in 1962. Gibson won 2 of 3 games he pitched in the 1964 World Series, then won 20 games in a season for the first time in 1965. Gibson also pitched three complete game victories in the 1967 World Series.

The pinnacle of Gibson's career was 1968, when he posted a 1.12 ERA for the season and then recorded 17 strikeouts in Game 1 of the 1968 World Series. Gibson threw a no-hitter in 1971 but began experiencing swelling in his knee in subsequent seasons. At the time of his retirement in 1975, Gibson ranked second only to Walter Johnson among major league pitchers in career strikeouts.[1]

After retiring as a player in 1975, Gibson later served as pitching coach for his former teammate Joe Torre. At one time a special instructor coach for the St. Louis Cardinals, Gibson was later selected for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team in 1999. Gibson was the author of the memoir Pitch by Pitch, with Lonnie Wheeler. Gibson died of pancreatic cancer on October 2, 2020, exactly 52 years after his memorable 1968 World Series Game 1 performance in which he struck out 17 Detroit Tigers.

Early life

Gibson was born in Omaha, the last of Pack and Victoria Gibson's seven children (five boys and two girls).[2][3] Gibson's father died of tuberculosis three months prior to Gibson's birth, and Gibson was named Pack Robert Gibson in his father's honor.[3][4] While he revered his father's legacy, Gibson disliked the name Pack, and later changed his first name to Robert.[4][5] Despite a childhood that included health problems like rickets, and a serious case of either asthma or pneumonia when he was three, Gibson was active in sports in both informal and organized settings, particularly baseball and basketball.[6] Gibson's brother Josh (no relation to the Negro leagues star player), who was 15 years his senior, had a profound effect on his early life, serving as a mentor to him.[7] Gibson played on a number of youth basketball and baseball teams his brother coached, many of which were organized through the local YMCA.[8]

Gibson attended Omaha Technical High School, where he participated on the track, basketball, and baseball teams.[9] Health issues resurfaced for Gibson, though, and he needed a doctor's permission to compete in high school sports because of a heart murmur that occurred in tandem with a rapid growth spurt.[10] Gibson was named to the All-State basketball team during his senior year of high school by a newspaper in Lincoln, Nebraska, and soon after won a full athletic scholarship for basketball from Creighton University.[11] Indiana University had rejected him after stating their Negro athlete quota had already been filled.[12]

While at Creighton, Gibson majored in sociology, and continued to experience success playing basketball. At the end of Gibson's junior basketball season, he averaged 22 points per game, and made third team Jesuit All-American.[13] As his graduation from Creighton approached, the spring of 1957 proved to be a busy time for Gibson. Aside from getting married, Gibson had garnered the interest of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team and the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team.[14] In 1957, Gibson received a $3,000 bonus (a notable sum at that time) to sign with the Cardinals.[5] He delayed his start with the organization for a year, playing basketball with the Globetrotters.[15] However, he gave up as a travelling member due to long travels and many double-headers.[12]

Baseball career

Gibson was assigned to the Cardinals' big league roster for the start of the 1959 season, recording his Major League debut on April 15 as a relief pitcher.[5] Reassigned to the Cardinals minor league affiliate the Omaha Cardinals soon after, Gibson returned to the Major Leagues on July 30 as a starting pitcher, earning his first Major League win that day.[16] Gibson's experience in 1960 was similar, pitching nine innings for the Cardinals before shuffling between the Cardinals and their Rochester affiliate until mid-June.[17] After posting a 3–6 record with a 5.61 ERA, Gibson traveled to Venezuela to participate in winter baseball at the conclusion of the 1960 season.[18] Cardinals manager Solly Hemus shuffled Gibson between the bullpen and the starting pitching rotation for the first half of the 1961 season.[19] In a 2011 documentary, Gibson indicated that Hemus's racial prejudice played a major role in his misuse of Gibson, as well as of teammate Curt Flood, both of whom were told by Hemus that they would not make it as major leaguers and should try something else.[20] Hemus was replaced as Cardinals manager in July 1961 by Johnny Keane, who had been Gibson's manager on the Omaha minor league affiliate several years prior.[21] Keane and Gibson shared a positive professional relationship, and Keane immediately moved Gibson into the starting pitching rotation full-time. Gibson proceeded to compile an 11–6 record the remainder of the year, and posted a 3.24 ERA for the full season.[5][22] Off the field, Bill White, Curt Flood, and Gibson started a civil rights movement to make all players live in the same clubhouse and hotel rooms, and led the St. Louis Cardinals to become the first sports team to end segregation, three years before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the "Great Society" legislation in 1964.[12]

1962–1967

In late May of the 1962 season Gibson pitched 22 2⁄3 consecutive scoreless innings on his way to being named to his first National League All-Star team.[24] Because of an additional All-Star Game played each season from 1959 to 1962, Gibson was named to the second 1962 N.L. All-Star game as well, where he pitched two innings.[25] After suffering a fractured ankle late in the season, Gibson, sometimes referred to by the nickname "Hoot" (a reference to western film star Hoot Gibson), still finished 1962 with his first 200 plus strikeout season.[5][21][25] The rehabilitation of Gibson's ankle was a slow process, and by May 19 of the 1963 season he had recorded only one win.[26] Gibson then turned to rely on his slider and two different fastball pitches to reel off six straight wins prior to late July.[27] Gibson and all other National League pitchers benefited from a rule change that expanded the strike zone above the belt buckle.[28] Adding to his pitching performances was Gibson's offensive production, with his 20 RBIs outmatching the combined RBI output of entire pitching staffs on other National League teams.[29] Even with Gibson's 18 wins and the extra motivation of teammate Stan Musial's impending retirement, the Cardinals finished six games out of first place.[30]

Building on their late-season pennant run in 1963, the 1964 Cardinals developed a strong camaraderie that was noted for being free of the racial tension that predominated in the United States at that time.[31][32] Part of this atmosphere stemmed from the integration of the team's spring training hotel in 1960, and Gibson and teammate Bill White worked to confront and stop use of racial slurs within the team.[33] On August 23, the Cardinals were 11 games behind the Philadelphia Phillies and remained six-and-a-half games behind on September 21.[34] The combination of a nine-game Cardinals winning streak and a ten-game Phillies losing streak then brought the season down to the final game. The Cardinals faced the New York Mets, and Gibson entered the game as a relief pitcher in the fifth inning.[34] Aware that the Phillies were ahead of the Cincinnati Reds 4–0 at the time he entered the game, Gibson proceeded to pitch four innings of two-hit relief, while his teammates scored 11 runs of support to earn the victory.[34]

They next faced the New York Yankees in the 1964 World Series. Gibson was matched against Yankees starting pitcher Mel Stottlemyre for three of the Series' seven games, with Gibson losing Game 2, then winning Game 5.[35] In Game 7, Gibson, who only had 2 days rest, pitched into the ninth inning, where he allowed home runs to Phil Linz and Clete Boyer, making the score 7–5 Cardinals.[36] With Ray Sadecki and Barney Schultz warming up in the Cardinal bullpen, Gibson retired Bobby Richardson for the final out, giving the Cardinals their first World Championship since 1946.[36] Along with his two victories, Gibson set a new World Series record by striking out 31 batters.[37]

Gibson made the All-Star team again in the 1965 season, and when the Cardinals were well out of the pennant race by August, attention turned on Gibson to see if he could win 20 games for the first time.[38] Gibson was still looking for win number 20 on the last day of the season, a game where new Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst rested many of the regular players.[39] Gibson still prevailed against the Houston Astros by a score of 5–2.[39] The 1966 season marked the opening of Busch Memorial Stadium for the Cardinals, and Gibson was selected to play in the All-Star Game in front of the hometown crowd that year as well.[40]

The Cardinals built a 3 1⁄2-game lead prior to the 1967 season All-Star break, and Gibson pitched the seventh and eighth innings of the 1967 All-Star game. Gibson then faced the Pittsburgh Pirates on July 15, when Roberto Clemente hit a line drive off Gibson's right leg.[41] Unaware his leg had been fractured, Gibson faced three more batters before his right fibula bone snapped above the ankle.[42] After Gibson returned on September 7, the Cardinals secured the National League pennant on September 18, 10 1⁄2 games ahead of the San Francisco Giants.[43][44][45]

In the 1967 World Series against the Boston Red Sox, Gibson allowed only three earned runs and 14 hits over three complete-game victories in Games 1, 4 (five-hit shutout), and 7, the latter two marks tying Christy Mathewson's 1905 World Series record. Just as he had in 1964, Gibson pitched a complete-game victory in Game 7, against Cy Young winner Jim Lonborg, who pitched a 1-hitter in Game 2. Gibson also contributed offensively in Game 7 by hitting a home run that made the game 3–0.[46][47] Gibson became the only pitcher to be on the mound for the final out of Game 7 of a World Series multiple times.[48] Unlike his last win as World Series MVP, he finally got the men's suit endorsement that eluded him in 1964.[12] He also gained endorsement and sponsorship for his asthma medication, namely Primateme mist inhaler and tablets.[12]

1968—Year of the Pitcher

The 1968 season became known as "The Year of the Pitcher", and Gibson was at the forefront of pitching dominance. His earned run average was 1.12, a live-ball era record, as well as the major league record in 300 or more innings pitched. It was the lowest major league ERA since Dutch Leonard's 0.96 mark 54 years earlier.[49] Gibson threw 13 shutouts, three fewer than fellow Nebraskan Grover Alexander's 1916 major league record of 16.[50] He won all 12 starts in June and July, pitching a complete game every time, (eight of which were shutouts), and allowed only six earned runs in 108 innings pitched (a 0.50 ERA). Gibson pitched 47 consecutive scoreless innings during this stretch, at the time the third-longest scoreless streak in major league history. He also struck out 91 batters, and he won two-consecutive NL Player of the Month awards.[51] Gibson finished the season with 28 complete games out of 34 games started. Of the games he didn't complete, he was pinch-hit for, meaning Gibson was not removed from the mound for another pitcher for the entire season. He also only conceded a total of 38 earned runs.[12][52]

Gibson won the National League MVP Award, not until Clayton Kershaw in 2014 would another National League pitcher do so.[53] With Denny McLain winning the American League's Most Valuable Player award, 1968 remains, to date, the only year both MVP Awards went to pitchers with McLain compiling a record of 31–6 record for the Detroit Tigers. For the 1968 season, opposing batters only had a batting average of .184, an on-base percentage of .233, and a slugging percentage of .236. Gibson lost nine games against 22 wins, despite his record-setting low 1.12 ERA as the anemic batting throughout baseball included his own Cardinal team. The 1968 Cardinals had one .300 hitter, while the team-leading home run and RBI totals were just 16 and 79, respectively. Gibson lost two 1–0 games, one of which against San Francisco Giants pitcher Gaylord Perry's no-hitter on September 17. The Giants' run in that game came on a first-inning home run by light-hitting Ron Hunt—the second of two he would hit the entire season and one of only 11 that Gibson allowed in 304 2⁄3 innings. [54] The year also was notable for Don Drysdale pitching a record six consecutive shutouts and 58 2⁄3 consecutive scoreless innings.

In Game 1 of the 1968 World Series, Gibson struck out 17 Detroit Tigers to set a World Series record for strikeouts in one game, which still stands today (breaking Sandy Koufax's record of 15 in Game 1 of the 1963 World Series).[49][55][56] He also joined Ed Walsh as the only pitchers to strike out at least one batter in each inning of a World Series game, Walsh having done so in Game Three of the 1906 World Series. After allowing a leadoff single to Mickey Stanley in the ninth inning, Gibson finished the game by striking out Tiger sluggers Al Kaline, Norm Cash, and Willie Horton in succession. Recalling the performance, Tigers outfielder Jim Northrup remarked: "We were fastball hitters, but he blew the ball right by us. And he had a nasty slider that was jumping all over the place."[57]

Gibson next pitched in Game 4 of the 1968 World Series, defeating the Tigers' ace pitcher Denny McLain 10–1.[58] The teams continued to battle each other, setting the stage for another winner-take-all Game 7 in St. Louis on October 10, 1968.[59] In this game Gibson was matched against Tigers pitcher Mickey Lolich and the two proceeded to hold their opponents scoreless for the first six innings.[60] In the top of the seventh, Gibson retired the first two batters before allowing two consecutive singles.[60] Detroit batter Jim Northrup then hit a two-run triple over the head of center fielder Curt Flood, leading to Detroit's Series win.[61]

The overall pitching statistics in MLB's 1968 season, led by Gibson and McLain's record-setting performances, are often cited as one of the reasons for Major League Baseball's decision to alter pitching-related rules.[62] Sometimes known as the "Gibson rules", MLB lowered the pitcher's mound in 1969 from 15 inches (380 mm) to 10 inches (250 mm) and reduced the height of the strike zone from the batter's armpits to the jersey letters.[58]

1969–1975

Aside from the rule changes set to take effect in 1969, cultural and monetary influences increasingly began impacting baseball, as evidenced by nine players from the Cardinals 1968 roster who had not reported by the first week of spring training due to the status of their contracts.[63] On February 4, 1969, Gibson appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, and said the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) had suggested players consider striking before the upcoming season began.[64] However, Gibson himself had no immediate contract worries, as the $125,000 salary Gibson requested for 1969 was agreed to by team owner Gussie Busch and the Cardinals, setting a new franchise record for the highest single-season salary.[65]

Despite the significant rule changes, Gibson's status as one of the league's best pitchers was not immediately affected. In 1969 he went 20–13 with a 2.18 ERA, 4 shutouts, and 28 complete games.[66] On May 12, 1969, Gibson struck out three batters on nine pitches in the seventh inning of a 6–2 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers.[67] Gibson became the ninth National League pitcher and the 15th pitcher in Major League history to throw an "immaculate inning". After pitching into the tenth inning of the July 4 game against the Cubs, Gibson was removed from a game without finishing an inning for the first time in more than 60 consecutive starts, a streak spanning two years.[68] After participating in the 1969 All-Star Game (his seventh selection), Gibson set another mark on August 16 when he became the third pitcher in Major League history to reach the 200-strikeout plateau in seven different seasons.[68][69]

Gibson experienced an up-and-down 1970 season, marked at the low point by a July slump where he resorted to experimenting with a knuckleball for the first time in his career.[70] Just as quickly, Gibson returned to form, starting a streak of seven wins on July 28, and pitching all 14 innings of a 5–4 win against the San Diego Padres on August 12. He would go on to win his fourth and final NL Player of the Month award for August (6–0, 2.31 ERA, 55 SO).[71] Gibson won 23 games in 1970, and was once again named the NL Cy Young Award winner.[72]

Gibson was sometimes used by the Cardinals as a pinch-hitter, and in 1970 he hit .303 for the season in 109 at-bats, which was over 100 points higher than teammate Dal Maxvill.[72] For his career, he batted .206 (274 for 1,328) with 44 doubles, 5 triples, 24 home runs (plus two more in the World Series), and 144 RBIs, stealing 13 bases and walking 63 times.[66]

Gibson achieved two highlights in August 1971. On the 4th, he defeated the Giants 7–2 at Busch Memorial Stadium for his 200th career victory.[15] Ten days later, he no-hit the eventual World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates 11–0 at Three Rivers Stadium.[73][74] Three of his 10 strikeouts in the game were to Willie Stargell, including the game's final out. The no-hitter was the first in Pittsburgh since Nick Maddox at Exposition Park in 1907; none had been pitched in the 62-year (mid-1909-to-mid-1970) history of Three Rivers Stadium's predecessor, Forbes Field. He was the second pitcher in Major League Baseball history, after Walter Johnson, to strike out over 3,000 batters, and the first to do so in the National League.[15] He accomplished this at home at Busch Stadium on July 17, 1974; the victim was César Gerónimo of the Cincinnati Reds.[75] Gibson began the 1972 season by going 0–5 but broke Jesse Haines's club record for victories on June 21 and finished the year with 19 wins.[76]

During the summer of 1974, Gibson felt hopeful he could put together a winning streak, but he continually encountered swelling in his knee.[77] In January 1975, Gibson announced he would retire at the end of the 1975 season, admittedly using baseball to help cope with his recent divorce from his former wife, Charline.[78] During the 1975 season, he went 3–10 with a 5.04 ERA.[66]

In the eight seasons from 1963 to 1970, Gibson posted a win–loss record of 156–81, for a .658 winning percentage.[66][79] He won nine Gold Glove Awards, was awarded the World Series MVP Award in 1964 and 1967, and won Cy Young Awards in 1968 and 1970.[80][81][82]

Don't mess with "Hoot"

Gibson was a fierce competitor who rarely smiled and was known to throw brushback pitches to establish dominance over the strike-zone and intimidate the batter, similar to his contemporary and fellow Hall of Famer Don Drysdale.[84] Even so, Gibson had good control and hit only 102 batters in his career (fewer than Drysdale's 154).[66]

Gibson was surly and brusque even with his teammates. When his catcher Tim McCarver went to the mound for a conference, Gibson brushed him off, saying "The only thing you know about pitching is that it's hard to hit."[85]

Gibson casually disregarded his reputation for intimidation, though, saying that he made no concerted effort to seem intimidating. However, there is an interview in which he admits that if a batter homered off one of his best pitches, he would hit that batter in his next at bat. He joked in an interview with a St. Louis public radio station that the only reason he made faces while pitching was because he needed glasses and could not see the catcher's signals.[86]

Post-playing career

Before Gibson returned to his home in Omaha at the end of the 1975 season, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine offered him an undefined job that was contingent on approval from higher-ranking club officials.[87] Unsure of his future career path, Gibson declined and used the motor home the Cardinals had given him as a retirement gift to travel across the western United States during the 1975 offseason. Returning to Omaha, Gibson continued to serve on the board of a local bank, was at one point the principal investor in radio station KOWH, and started "Gibson's Spirits and Sustenance" restaurant, sometimes working twelve-hour days as owner/operator.[88]

Gibson returned to baseball in 1981 after accepting a coaching job with Joe Torre, who was then manager of the New York Mets.[89] Torre termed Gibson's position "attitude coach", the first such title in Major League history.[90] After Torre and his coaching staff were let go at the end of the 1981 season, Torre moved on to manage the Atlanta Braves in 1982, hiring Gibson as a pitching coach.[91] The Braves proceeded to challenge for the National League pennant for the first time since 1969, ultimately losing to the Cardinals in the 1982 National League Championship Series.[92] Gibson remained with Torre on the Braves' coaching staff until the end of the 1984 season.[93] Gibson then took to hosting a pre- and postgame show for Cardinals baseball games on radio station KMOX from 1985 until 1989.[94] Gibson also served as color commentator for baseball games on ESPN in 1990 but declined an option to continue the position over concerns he would have to spend too much time away from his family.[95] In 1995, Gibson again served as pitching coach on a Torre-led staff, this time returning to the Cardinals.[72]

Personal life

Gibson was a father to three children: two with his first wife, Charline, and one with his second wife, Wendy.[96]

In July 2019, Gibson's longtime agent Dick Zitzmann announced that Gibson had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer several weeks earlier and was due to begin chemotherapy.[97] Gibson died on October 2, 2020, at age 84, under hospice care after fighting pancreatic cancer for more than a year.[98]

Honors

| |

| Bob Gibson's number 45 was retired by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1975. |

Gibson's jersey number 45 was retired by the St. Louis Cardinals on September 1, 1975. In 1981 he was inducted into the Baseball Hall Of Fame.[99] In 1999 he ranked Number 31 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and was elected to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[100][101] He has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[102] A bronze statue of Gibson by Harry Weber is located in front of Busch Stadium, commemorating Gibson along with other St. Louis Cardinals greats. Another statue of Gibson was unveiled outside of Werner Park in Gibson's home city, Omaha, Nebraska, in 2013.[103][104] The street on the north side of Rosenblatt Stadium, former home of the College World Series in his hometown of Omaha, is named Bob Gibson Boulevard. In January 2014, the Cardinals announced Gibson among 22 former players and personnel to be inducted into the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame Museum for the inaugural class of 2014.[105] At the time of his death, Gibson still lead the Cardinals franchise's pitching records in wins (251), games started (482), complete games (255), shutouts (56), innings pitched (3,884.1) and strikeouts (3,117) along with a 2.91 ERA.[106]

Career MLB statistics

Pitching

| Year | Team | W | L | G | CG | ERA | SHO | IP | H | ER | HR | BB | SO | WHIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | STL | 3 | 5 | 13 | 2 | 3.33 | 1 | 75.2 | 77 | 28 | 4 | 39 | 48 | 1.533 |

| 1960 | STL | 3 | 6 | 27 | 2 | 5.61 | 0 | 86.2 | 97 | 54 | 7 | 48 | 69 | 1.673 |

| 1961 | STL | 13 | 12 | 35 | 10 | 3.24 | 2 | 211.1 | 186 | 76 | 13 | 119 | 166 | 1.443 |

| 1962 | STL | 15 | 13 | 32 | 15 | 2.85 | 5 | 233.2 | 174 | 74 | 15 | 95 | 208 | 1.151 |

| 1963 | STL | 18 | 9 | 36 | 14 | 3.39 | 2 | 254.2 | 224 | 96 | 19 | 96 | 204 | 1.257 |

| 1964 | STL | 19 | 12 | 40 | 17 | 3.01 | 2 | 287.1 | 250 | 96 | 25 | 86 | 245 | 1.169 |

| 1965 | STL | 20 | 12 | 38 | 20 | 3.07 | 6 | 299 | 243 | 102 | 34 | 103 | 270 | 1.157 |

| 1966 | STL | 21 | 12 | 35 | 20 | 2.44 | 5 | 280.1 | 210 | 76 | 20 | 78 | 225 | 1.027 |

| 1967 | STL | 13 | 7 | 24 | 10 | 2.98 | 2 | 175.1 | 151 | 58 | 10 | 40 | 147 | 1.089 |

| 1968 | STL | 22 | 9 | 34 | 28 | 1.12 | 13 | 304.2 | 198 | 38 | 11 | 62 | 268 | 0.853 |

| 1969 | STL | 20 | 13 | 35 | 28 | 2.18 | 4 | 314 | 251 | 76 | 12 | 95 | 269 | 1.102 |

| 1970 | STL | 23 | 7 | 34 | 23 | 3.12 | 3 | 294 | 262 | 102 | 13 | 88 | 274 | 1.190 |

| 1971 | STL | 16 | 13 | 31 | 20 | 3.04 | 5 | 245.2 | 215 | 83 | 14 | 76 | 185 | 1.185 |

| 1972 | STL | 19 | 11 | 34 | 23 | 2.46 | 4 | 278 | 226 | 76 | 14 | 88 | 208 | 1.129 |

| 1973 | STL | 12 | 10 | 25 | 13 | 2.77 | 1 | 195 | 159 | 60 | 12 | 57 | 142 | 1.108 |

| 1974 | STL | 11 | 13 | 33 | 9 | 3.83 | 1 | 240 | 236 | 102 | 24 | 104 | 129 | 1.417 |

| 1975 | STL | 3 | 10 | 22 | 1 | 5.04 | 0 | 109 | 120 | 61 | 10 | 62 | 60 | 1.670 |

| Category | W | L | G | CG | ERA | SHO | IP | H | ER | HR | BB | SO | WHIP | O-AVE | O-OBP | O-SLG | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[66] | 251 | 174 | 528 | 255 | 2.91 | 56 | 3,884.1 | 3,279 | 1,258 | 257 | 1,336 | 3,117 | 1.188 | .228 | .297 | .325 | 127 |

Records held

- Most Consecutive Quality Starts (six or more innings and three or fewer earned runs) (since 1920): 26 starts; September 12, 1967 – July 30, 1968.[107]

- Most Consecutive Starts with 6-Plus Innings Pitched: 78 starts; September 12, 1967 – May 2, 1970.[108]

- National League Shutout Championships in Live-Ball Era: Led or tied four times in 1962 (5), 1966 (5), 1968 (13), and 1971 (5). Record shared with Warren Spahn. Pete Alexander was a six-time shutout champion from 1911 to 1921.[109]

- Gold Gloves for Pitchers: Nine consecutive Gold Gloves (1965–1973) is third all-time among pitchers.[110]

- Single-Season Earned Run Average: 1.12 ERA during 1968 is the lowest in live-ball era and third-best all-time.[111]

- Most Strikeouts During a World Series Game: 17 strikeouts during Game 1 of 1968 World Series.[111]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball all-time leaders in home runs by pitchers

- List of Major League Baseball career hit batsmen leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career putouts as a pitcher

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball pitchers who have hit home runs in the postseason

- List of Major League Baseball pitchers who have struck out three batters on nine pitches

- List of Major League Baseball players who spent their entire career with one franchise

- List of Major League Baseball retired numbers

- List of Major League Baseball single-inning strikeout leaders

- List of St. Louis Cardinals team records

References

- "In his day, St. Louis Cardinals great Bob Gibson was feared like no other pitcher". espn.com. espn.com. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 11, 14

- Halberstam 1994: 98

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 11

- "Bob Gibson". Retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 12

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 12–15

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 15–19

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 20–23

- Reidenbaugh 1993: 106

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 23, 32

- Max Carey (April 21, 2018), SportsCentury: Bob Gibson, retrieved June 23, 2019

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 36–37

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 40–43

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 54–55

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 62

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 63

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 64–65

- "HBO: The Curious Case of Curt Flood". Home Box Office, Inc. Archived from the original on September 2, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 65

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 43–44, 65–66

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 76

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 70–72

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 72–73

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 74

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 75

- Halberstam 1994: 119

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 78

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 79–80

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 82–83

- Halberstam 1994: 113–115

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 58–59

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 89

- Halberstam 1994: 322–347

- Halberstam 1994: 349–350

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 102

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 115–116

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 116

- O'Neill 2005: 32

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 135

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 136

- "1967 National League Season Summary - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "1967 St. Louis Cardinals Statistics - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 139

- Schoor 1990: 298–299

- "1967 World Series Game 7, St. Louis Cardinals at Boston Red Sox, October 12, 1967 - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "All of MLB: 40 Plate Appearances in 1903-2016 Postseason, as last play of game, Game 7 and World Series: 1903-2016 Results". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- "Bob Gibson". Baseballhall.org. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "1968 National League Pitching Leaders - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "MLB Major League Baseball Players of the Month - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Bob Gibson 1968 Pitching Gamelogs Archived June 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Baseball-Reference.com

- "1968 Awards Voting - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- September 17, 1968 Cardinals-Giants box score Archived September 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at Baseball Reference

- "All-time and Single-Season World Series Pitching Leaders - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- 1968 World Series Game 1 box score Archived September 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at Baseball Reference

- Sargent, Jim. "The Baseball Biography Project: Jim Northrup". Society for American Baseball Research. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- Feldmann 2011: 2

- Feldmann 2011: 1

- Schoor 1990: 303

- Feldmann 2011: 1–3

- Rains 2003: 55

- Feldmann 2011: 11

- Feldmann 2011: 10

- Feldmann 2011: 12,14

- "Bob Gibson Statistics and History". Sports Reference, LLC. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- "Los Angeles Dodgers at St. Louis Cardinals Box Score, May 12, 1969 - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Feldmann 2011: 31

- "National League 9, American League 3". Retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Feldmann 2011: 80

- Feldmann 2011: 81

- "Bob Gibson". Retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- "St. Louis Cardinals at Pittsburgh Pirates Box Score, August 14, 1971 - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Inc., Baseball Almanac. "Box Score of Game played on Saturday, August 14, 1971 at Three Rivers Stadium". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Retrosheet Boxscore: Cincinnati Reds 6, St. Louis Cardinals 4". Retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 235–237

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 244

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 245

- Inc., Baseball Almanac. "Bob Gibson Baseball Stats by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Rains 2003: 119

- "MLB Postseason Willie Mays World Series MVP Awards & All-Star Game MVP Award Winners - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "MLB Most Valuable Player MVP Awards & Cy Young Awards Winners - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Cafardo, Nick. "Resources a good sign for Jays". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Hall Of Famer Defends Inside Pitches To Batter", by Art Spander, Baseball Digest, November 1987, Vol. 46, No. 11, ISSN 0005-609X

- Tim McCarver's Baseball for Brain Surgeons and Other Fans: Understanding and Interpreting the Game So You Can Watch It Like a Pro (Google eBook) Archived June 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, by Tim McCarver and Danny Peary, Random House Publishing Group, May 22, 2013

- "St. Louis Public Radio - St. Louis on the Air". Stlpublicradio.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 249–250

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 257–259

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 257

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 262

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 263–264

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 264–267

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 268–269

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 271–272

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 272

- Gibson and Wheeler 1994: 258

- Post-Dispatch store. "Cards' Hall of Famer Gibson being treated for pancreatic cancer | Cardinal Beat". stltoday.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Hummel, Rick. "Cardinals Hall of Famer Bob Gibson dies at 84 after bout with cancer | St. Louis Cardinals". stltoday.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- "Cardinals Retired Numbers". St. Louis Cardinals. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Smith 1998: 72

- "The All-Century Team". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". Stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- Rob White. "Bob Gibson statue unveiled at Werner Park". Omaha.com. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Bob Gibson statue unveiled at Werner Park". Ballparkdigest.com. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Cardinals Press Release (January 18, 2014). "Cardinals establish Hall of Fame & detail induction process". Stlouis.cardinals. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- https://www.mlb.com/cardinals/fans/tribute/bob-gibson

- Mead, Doug. "Major League Baseball's 10 Most Insane Pitching Streaks". Bleacherreport.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Mead, Doug. "Major League Baseball's 10 Most Insane Pitching Streaks". Bleacherreport.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Yearly League Leaders &Records for Shutouts - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "MLB National League Gold Glove Award Winners - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Keri: Bob Gibson's legendary 1968 season". ESPN.com. February 7, 2008. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

Further reading

- Angell, Roger (September 22, 1980). "Distance". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- Banks, Kerry (2010). Baseball's Top 100: The Game's Greatest Records. Vancouver: Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-507-7. OCLC 436336541.

- Feldmann, Doug (2011). Gibson's Last Stand: The Rise, Fall, and Near Misses of the St. Louis Cardinals, 1969–1975. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1950-3. OCLC 711050960.

- Gibson, Bob; Lonnie Wheeler (1994). Stranger To The Game. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-84794-5. OCLC 30110624.

- Halberstam, David (1994). October 1964. New York: Villard. ISBN 978-0-679-41560-2. OCLC 30109791.

- O'Neill, Dan; Joe Buck; Robert W. Duffy; Bernie Miklasz (2005). Mike Smith (ed.). Busch Stadium Moments. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. ISBN 978-0-9661397-3-0. OCLC 62385897.

- Rains, Rob (2003). Cardinal Nation (2nd ed.). St. Louis: The Sporting News. ISBN 0-89204-727-5. OCLC 52577755.

- Reidenbaugh, Lowell (1993). Hoppel, Joe (ed.). Baseball's Hall of Fame:Cooperstown, where the legends live forever (3 ed.). New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-09277-4. OCLC 27381477.

- Schoor, Gene (1990). The History of the World Series. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-07995-4. OCLC 21303516.

- Smith, Ron (1998). The Sporting News Selects Baseball's 100 Greatest Players. St. Louis: The Sporting News. ISBN 978-0-89204-608-9. OCLC 40392319.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bob Gibson. |

- Bob Gibson at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Bob Gibson at Find a Grave

- Bob Gibson at SABR BioProject

- Bob Gibson at Pura Pelota (Venezuelan Professional Baseball League)

- "Bob Gibson photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- "Hall Of Famer Defends Inside Pitches To Batter", Baseball Digest, November 1987

- Bob Gibson Oral History Interview - National Baseball Hall of Fame Digital Collection

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Frank Robinson Don Drysdale Bill Singer |

NL Player of the Month September 1964 June & July 1968 August 1970 |

Succeeded by Joe Torre Pete Rose Willie Stargell |

| Preceded by Rick Wise |

No-hitter pitcher August 14, 1971 |

Succeeded by Burt Hooton |

| Sporting positions | ||

| Preceded by Joe Coleman |

St. Louis Cardinals pitching coach 1995 |

Succeeded by Dave Duncan |