History of Protestantism in the United States

Christianity was introduced with the first European settlers beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries. Colonists from Northern Europe introduced Protestantism in its Anglican and Reformed forms to Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New Netherland, Virginia Colony, and Carolina Colony. The first arrivals were adherents to Anglicanism, Congregationalism, Presbyterianism, Lutheranism, Quakerism, Anabaptism and the Moravian Church from British, German, Dutch, and Nordic stock. America began as a significant Protestant majority nation. Significant minorities of Roman Catholics and Jews did not arise until the period between 1880 and 1910.

Altogether, Protestants comprised the majority of the population until 2012 when the Protestant share of U.S. population dropped to 48%, thus ending its status as religion of the majority.[1][2] The decline is attributed mainly to the dropping membership of the Mainline Protestant churches,[1][3] while Evangelical Protestant and Black churches are stable or continue to grow.[1] Today, 46.5% of the United States population is either Mainline Protestant, Evangelical Protestant, or a Black church attendee.

Early Colonial era

Virginia

Anglican chaplain Robert Hunt was among the first group of English colonists, arriving in 1607. In 1619, the Church of England was formally established as the official religion in the colony, and would remain so until it was disestablished shortly after the American Revolution.[4] Establishment meant that local tax funds paid the parish costs, and that the parish had local civic functions such as poor relief. The upper class planters controlled the vestry, which ran the parish and chose the minister. The church in Virginia was controlled by the Bishop of London, who sent priests and missionaries but there were never enough, and they reported very low standards of personal morality.[5][6]

The colonists were typically inattentive, uninterested, and bored during church services, according to the ministers, who complained that the people were sleeping, whispering, ogling the fashionably dressed women, walking about and coming and going, or at best looking out the windows or staring blankly into space.[7] There were too few ministers for the widely scattered population, so ministers encouraged parishioners to become devout at home, using the Book of Common Prayer for private prayer and devotion (rather than the Bible). This allowed devout Anglicans to lead an active and sincere religious life apart from the unsatisfactory formal church services. The stress on personal piety opened the way for the First Great Awakening, which pulled people away from the established church.[8] By the 1760s, dissenting Protestants, especially Baptists and Methodists, were growing rapidly and started challenging the Anglicans for moral leadership.[9][10]

New England

A small group of Pilgrims settled the Plymouth Colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, seeking refuge from conflicts in England which led up to the English Civil War.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. Puritans were English Protestants who wished to reform and purify the Church of England in the New World of what they considered to be unacceptable residues of Roman Catholicism. Within two years, an additional 2,000 settlers arrived. Beginning in 1630, some 20,000 Puritans emigrated as families to New England to gain the liberty to worship as they chose. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalists". The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation". By the mid-18th century, the Puritans were known as Congregationalists.[11]

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings before local magistrates followed by county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in Essex, Suffolk and Middlesex counties of colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693. Over 150 people were arrested and imprisoned. Church leaders finally realized their mistake, ended the trials, and never repeated them.[12]

Tolerance in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania

Roger Williams, who preached religious tolerance, separation of church and state, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other religious refugees from the Puritan community. Some migrants who came to Colonial America were in search of the freedom to practice forms of Christianity which were prohibited and persecuted in Europe. Since there was no state religion, in fact there was not yet a state, and since Protestantism had no central authority, religious practice in the colonies became diverse.

The Religious Society of Friends formed in England in 1652 around leader George Fox. Quakers were severely persecuted in England for daring to deviate so far from Anglicanism. This reign of terror impelled Friends to seek refuge in New Jersey in the 1670s, formally part of New Netherland, where they soon became well entrenched. In 1681, when Quaker leader William Penn parlayed a debt owed by Charles II to his father into a charter for the Province of Pennsylvania, many more Quakers were prepared to grasp the opportunity to live in a land where they might worship freely. By 1685, as many as 8,000 Quakers had come to Pennsylvania. Although the Quakers may have resembled the Puritans in some religious beliefs and practices, they differed with them over the necessity of compelling religious uniformity in society.

The first group of Germans to settle in Pennsylvania arrived in Philadelphia in 1683 from Krefeld, Germany, and included Mennonites and possibly some Dutch Quakers. These mostly German settlers would become the Pennsylvania Dutch.

The efforts of the founding fathers to find a proper role for their support of religion—and the degree to which religion can be supported by public officials without being inconsistent with the revolutionary imperative of freedom of religion for all citizens—is a question that is still debated in the country today.

Anti-Catholicism

American Anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Reformation. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to the New World by British colonists who were predominantly Protestant, and who opposed not only the Roman Catholic Church but also the Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently reformed[13] (see also Ritualism). Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans, were fleeing religious persecution, early American religious culture exhibited a more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations, thus were Roman Catholics forbidden from holding public office.

Monsignor Ellis wrote that a universal anti-Catholic bias was "vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia" and that Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics.[14] Ellis also wrote that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

18th century

Against a prevailing view that 18th-century Americans had not perpetuated the first settlers' passionate commitment to their faith, scholars now identify a high level of religious energy in colonies after 1700. According to one expert, religion was in the "ascension rather than the declension"; another sees a "rising vitality in religious life" from 1700 onward; a third finds religion in many parts of the colonies in a state of "feverish growth." Figures on church attendance and church formation support these opinions. Between 1700 and 1740, an estimated 75-80% of the population attended churches, which were being built at a headlong pace.

By 1780 the percentage of adult colonists who adhered to a church was between 10 and 30%, not counting slaves or Native Americans. North Carolina had the lowest percentage at about 4%, while New Hampshire and South Carolina were tied for the highest, at about 16%.[15]

Great Awakening

Evangelicalism is difficult to date and to define. Scholars have argued that, as a self-conscious movement, evangelicalism did not arise until the mid-17th century, perhaps not until the Great Awakening itself. The fundamental premise of evangelicalism is the conversion of individuals from a state of sin to a "new birth" through preaching of the Word. The Great Awakening refers to a northeastern Protestant revival movement that took place in the 1730s and 1740s.

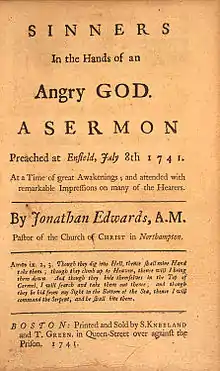

The first generation of New England Puritans required that church members undergo a conversion experience that they could describe publicly. Their successors were not as successful in reaping harvests of redeemed souls. The movement began with Jonathan Edwards, a Massachusetts preacher who sought to return to the Pilgrims' strict Calvinist roots. British preacher George Whitefield and other itinerant preachers continued the movement, traveling across the colonies and preaching in a dramatic and emotional style. Followers of Edwards and other preachers of similar religious piety called themselves the "New Lights," as contrasted with the "Old Lights," who disapproved of their movement. To promote their viewpoints, the two sides established academies and colleges, including Princeton and Williams College. The Great Awakening has been called the first truly American event.

The supporters of the Awakening and its evangelical thrust—Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists—became the largest American Protestant denominations by the first decades of the 19th century. By the 1770s, the Baptists were growing rapidly both in the north (where they founded Brown University), and in the South. Opponents of the Awakening or those split by it—Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists—were left behind.

American Revolution

The Revolution split some denominations, notably the Church of England, whose ministers were bound by oath to support the king, and the Quakers, who were traditionally pacifists. Religious practice suffered in certain places because of the absence of ministers and the destruction of churches, but in other areas, religion flourished.

The American Revolution inflicted deeper wounds on the Church of England in America than on any other denomination because the King of England was the head of the church. The Book of Common Prayer offered prayers for the monarch, beseeching God "to be his defender and keeper, giving him victory over all his enemies," who in 1776 were American soldiers as well as friends and neighbors of American Anglicans. Loyalty to the church and to its head could be construed as treason to the American cause. Patriotic American Anglicans, loathing to discard so fundamental a component of their faith as The Book of Common Prayer, revised it to conform to the political realities.

Another result of this was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant, that Anglicans elsewhere had shown some care in using too prominently due to their own reservations about the nature of the Church of England, and other Anglican bodies, vis-à-vis later radical reformers who were happier to use the term Protestant.

Massachusetts: church and state debate

After independence the American states were obliged to write constitutions establishing how each would be governed. For three years, from 1778 to 1780, the political energies of Massachusetts were absorbed in drafting a charter of government that the voters would accept.

One of the most contentious issues was whether the state would support the church financially. Advocating such a policy were the ministers and most members of the Congregational Church, which had been established, and hence had received public financial support, during the colonial period. The Baptists, who had grown strong since the Great Awakening, tenaciously adhered to their long-held conviction that churches should receive no support from the state.

The Constitutional Convention chose to support the church and Article Three authorized a general religious tax to be directed to the church of a taxpayers' choice. Despite substantial doubt that Article Three had been approved by the required two thirds of the voters, in 1780 Massachusetts authorities declared it and the rest of the state constitution to have been duly adopted. Such tax laws also took effect in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

In 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil.".[16]

19th century

Second Great Awakening

During the Second Great Awakening, Protestantism grew and took root in new areas, along with new Protestant denominations such as Adventism, the Restoration Movement, and groups such as Mormonism.[17] While the First Great Awakening was centered on reviving the spirituality of established congregations, the Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s), unlike the first, focused on the unchurched and sought to instill in them a deep sense of personal salvation as experienced in revival meetings.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Bishop Francis Asbury led the American Methodist movement as one of the most prominent religious leaders of the young republic. Traveling throughout the eastern seaboard, Methodism grew quickly under Asbury's leadership into one of the nation's largest and most influential denominations.

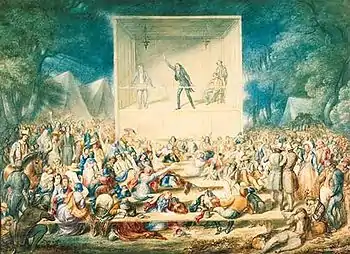

The principal innovation produced by the revivals was the camp meeting. The revivals were organized by Presbyterian ministers who modeled them after the extended outdoor communion seasons, used by the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, which frequently produced emotional, demonstrative displays of religious conviction. In Kentucky, the pioneers loaded their families and provisions into their wagons and drove to the Presbyterian meetings, where they pitched tents and settled in for several days.

When assembled in a field or at the edge of a forest for a prolonged religious meeting, the participants transformed the site into a camp meeting. The religious revivals that swept the Kentucky camp meetings were so intense and created such gusts of emotion that their original sponsors, the Presbyterians, soon repudiated them. The Methodists, however, adopted and eventually domesticated camp meetings and introduced them into the eastern United States, where for decades they were one of the evangelical signatures of the denomination.

Separation of church and state

In October 1801, members of the Danbury Baptists Associations wrote a letter to the new president-elect Thomas Jefferson. Baptists, being a minority in Connecticut, were still required to pay fees to support the Congregationalist majority. The Baptists found this intolerable. The Baptists, well aware of Jefferson's own unorthodox beliefs, sought him as an ally in making all religious expression a fundamental human right and not a matter of government largesse.

In his January 1, 1802 reply to the Danbury Baptist Association Jefferson summed up the First Amendment's original intent, and used for the first time anywhere a now-familiar phrase in today's political and judicial circles: the amendment established a "wall of separation between church and state." Largely unknown in its day, this phrase has since become a major Constitutional issue. The first time the U.S. Supreme Court cited that phrase from Jefferson was in 1878, 76 years later.

African American churches

The Christianity of the black population was grounded in evangelicalism. The Second Great Awakening has been called the "central and defining event in the development of Afro-Christianity." During these revivals Baptists and Methodists converted large numbers of blacks. However, many were disappointed at the treatment they received from their fellow believers and at the backsliding in the commitment to abolish slavery that many white Baptists and Methodists had advocated immediately after the American Revolution.

When their discontent could not be contained, forceful black leaders followed what was becoming an American habit—they formed new denominations. In 1787, Richard Allen and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the Methodist Church and in 1815 founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, which, along with independent black Baptist congregations, flourished as the century progressed.

Abolitionism

The first American movement to abolish slavery came in the spring of 1688 when German and Dutch Quakers of Mennonite descent in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia) wrote a two-page condemnation of the practice and sent it to the governing bodies of their Quaker church, the Society of Friends. Though the Quaker establishment took no immediate action, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, was an unusually early, clear and forceful argument against slavery and initiated the process of banning slavery in the Society of Friends (1776) and Pennsylvania (1780).

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society, formed 14 April 1775, in Philadelphia, primarily by Quakers who had strong religious objections to slavery.

After the American Revolutionary War, Quaker and Moravian advocates helped persuade numerous slaveholders in the Upper South to free their slaves. Theodore Weld, an evangelical minister, and Robert Purvis, a free African American, joined Garrison in 1833 to form the Anti-Slavery Society (Faragher 381). The following year Weld encouraged a group of students at Lane Theological Seminary to form an anti-slavery society. After the president, Lyman Beecher, attempted to suppress it, the students moved to Oberlin College. Due to the students' anti-slavery position, Oberlin soon became one of the most liberal colleges and accepted African American students. Along with Garrison, were Northcutt and Collins as proponents of immediate abolition. These two ardent abolitionists felt very strongly that it could not wait and that action needed to be taken right away.

After 1840 "abolition" usually referred to positions like Garrison's; it was largely an ideological movement led by about 3000 people, including free blacks and people of color, many of whom, such as Frederick Douglass, and Robert Purvis and James Forten in Philadelphia, played prominent leadership roles. Abolitionism had a strong religious base including Quakers, and people converted by the revivalist fervor of the Second Great Awakening, led by Charles Finney in the North in the 1830s. Belief in abolition contributed to the breaking away of some small denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church.

Evangelical abolitionists founded some colleges, most notably Bates College in Maine and Oberlin College in Ohio. The well-established colleges, such as Harvard, Yale and Princeton, generally opposed abolition, although the movement did attract such figures as Yale president Noah Porter and Harvard president Thomas Hill.

One historian observed that ritualist churches separated themselves from heretics rather than sinners; he observed that Episcopalians and Lutherans also accommodated themselves to slavery. (Indeed, one southern Episcopal bishop was a Confederate general.) There were more reasons than religious tradition, however, as the Anglican Church had been the established church in the South during the colonial period. It was linked to the traditions of landed gentry and the wealthier and educated planter classes, and the Southern traditions longer than any other church. In addition, while the Protestant missionaries of the Great Awakening initially opposed slavery in the South, by the early decades of the 19th century, Baptist and Methodist preachers in the South had come to an accommodation with it in order to evangelize with farmers and artisans. By the Civil War, the Baptist and Methodist churches split into regional associations because of slavery.[18]

After O'Connell's failure, the American Repeal Associations broke up; but the Garrisonians rarely relapsed into the "bitter hostility" of American Protestants towards the Roman Church. Some antislavery men joined the Know Nothings in the collapse of the parties; but Edmund Quincy ridiculed it as a mushroom growth, a distraction from the real issues. Although the Know-Nothing legislature of Massachusetts honored Garrison, he continued to oppose them as violators of fundamental rights to freedom of worship.

The abolitionist movement was strengthened by the activities of free African-Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old Biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament. African-American activists and their writings were rarely heard outside the black community; however, they were tremendously influential to some sympathetic white people, most prominently the first white activist to reach prominence, William Lloyd Garrison, who was its most effective propagandist. Garrison's efforts to recruit eloquent spokesmen led to the discovery of ex-slave Frederick Douglass, who eventually became a prominent activist in his own right.

Liberal Christianity

The "secularization of society" is attributed to the time of the Enlightenment. In the United States, religious observance is much higher than in Europe, and the United States' culture leans conservative in comparison to other western nations, in part due to the Christian element.

Liberal Christianity, exemplified by some theologians, sought to bring to churches new critical approaches to the Bible. Sometimes called liberal theology, liberal Christianity is an umbrella term covering movements and ideas within 19th- and 20th-century Christianity. New attitudes became evident, and the practice of questioning the nearly universally accepted Christian orthodoxy began to come to the forefront.

In the post-World War I era, Liberalism was the faster-growing sector of the American church. Liberal wings of denominations were on the rise, and a considerable number of seminaries held and taught from a liberal perspective as well. In the post-World War II era, the trend began to swing back towards the conservative camp in America's seminaries and church structures.

Fundamentalism

Christian fundamentalism began as a movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to reject influences of secular humanism and source criticism in modern Christianity. In reaction to liberal Protestant groups that denied doctrines considered fundamental to these conservative groups, they sought to establish tenets necessary to maintaining a Christian identity, the "fundamentals," hence the term fundamentalist.

Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by secular scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists grew in various denominations as independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity.

Over time, the movement divided, with the label Fundamentalist being retained by the smaller and more hard-line group(s). Evangelical has become the main identifier of the groups holding to the movement's moderate and earliest ideas.

Roman Catholics in the United States

By the 1850s, Roman Catholics had become the country's largest single denomination. Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled through immigration; by the end of the decade it would reach 7 million. These huge numbers of immigrant Catholics came from Ireland, Southern Germany, Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe. This influx would eventually bring increased political power for the Roman Catholic Church and a greater cultural presence, led at the same time to a growing fear of the Catholic "menace." As the 19th century wore on animosity waned, Protestant Americans realized that Roman Catholics were not trying to seize control of the government. Nonetheless, fears continued into the 20th century that there was too much "Catholic influence" on the government.

Anti-Catholic sentiment and violence

.jpg.webp)

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the 19th century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Fearing the end of time, some American Protestants who believed they were God's chosen people, went so far as to claim that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.[19]

The resulting "Nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.[20]

This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for raising the taxes of the country as well as for spreading violence and disease.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

The Catholic parochial school system developed in the early-to-mid-19th century partly in response to what was seen as anti-Catholic bias in American public schools. The recent wave of newly established Protestant schools is sometimes similarly attributed to the teaching of evolution (as opposed to creationism) in public schools.

Most states passed a constitutional amendment, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools, a possible outcome with heavy immigration from Catholic Ireland after the 1840s. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, in theory, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it were religious. However, no state school system had, by 2009, changed its laws to allow this.[21]

20th century

Scopes Monkey Trial

The Scopes Monkey Trial was an American legal case that tested the Butler Act, which made it unlawful, in any state-funded educational establishment in Tennessee, "to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals."[22] This is often interpreted as meaning that the law forbade the teaching of any aspect of the theory of evolution. The case was a critical turning point in the United States' creation-evolution controversy.

After the passage of the Butler Act, the American Civil Liberties Union financed a test case, where a Dayton, Tennessee high school teacher named John Scopes intentionally violated the Act. Scopes was charged on May 5, 1925 with teaching evolution from a chapter in a textbook which showed ideas developed from those set out in Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species. The trial pitted two of the pre-eminent legal minds of the time against one another; three-time presidential candidate, Congressman and former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan headed up the prosecution and prominent trial attorney Clarence Darrow spoke for the defense.[23] The famous trial was made infamous by the fictionalized accounts given in the 1955 play Inherit the Wind, the 1960 film adaptation, and the 1965, 1988, and 1999 television films of the same title.

Evangelicalism

In the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, there has been a marked rise in the evangelical movement. It began in the colonial era in the revivals of the First Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening in 1830–50. Balmer explains that:

Evangelicalism itself, I believe, is quintessentially North American phenomenon, deriving as it did from the confluence of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism. Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans – even as the North American context itself has profoundly shaped the various manifestations of evangelicalism.: fundamentalism, neo-evangelicalism, the holiness movement, Pentecostalism, the charismatic movement, and various forms of African-American and Hispanic evangelicalism.[24]

The 1950s saw a boom in the Evangelical church in America. The post–World War II prosperity experienced in the U.S. also had its effects on the church. Church buildings were erected in large numbers, and the Evangelical church's activities grew along with this expansive physical growth. In the southern U.S., the Evangelicals, represented by leaders such as Billy Graham, have experienced a notable surge displacing the caricature of the pulpit pounding country preachers of fundamentalism. The stereotypes have gradually shifted.

Evangelicals are as diverse as the names that appear: Billy Graham, Chuck Colson, J. Vernon McGee, or Jimmy Carter— or even Evangelical institutions such as Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (Boston) or Trinity Evangelical Divinity School(Chicago). Although there exists a diversity in the Evangelical community worldwide, the ties that bind all Evangelicals are still apparent: a "high view" of Scripture, belief in the Deity of Christ, the Trinity, salvation by grace through faith, and the bodily resurrection of Christ, to mention a few.

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism arose and developmented in 20th-century Christianity. The Pentecostal movement had its roots in the Pietism and the Holiness movement, and arose out of the meetings in 1906 at an urban mission on Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, California

The Azusa Street Revival and was led by William J. Seymour, an African American preacher and began with a meeting on April 14, 1906 at the African Methodist Episcopal Church and continued until roughly 1915. The revival was characterized by ecstatic spiritual experiences accompanied by speaking in tongues, dramatic worship services, and inter-racial mingling. It was the primary catalyst for the rise of Pentecostalism, and as spread by those who experienced what they believed to be miraculous moves of God there.

Many Pentecostals embrace the term Evangelical, while others prefer "Restorationist". Within classical Pentecostalism there are three major orientations:Wesleyan-Holiness, Higher Life, and Oneness.[25]

Pentecostalism would later birth the Charismatic movement within already established denominations; some Pentecostals use the two terms interchangeably. Pentecostalism claims more than 250 million adherents worldwide.[26] When Charismatics are added with Pentecostals the number increases to nearly a quarter of the world's 2 billion Christians.[27]

Data from the Pew Research Center that as of 2013, about 1.6 million adult Jews identify themselves as Christians, most are Protestant.[28][29][30] According to same data most of the Jews who identify themselves as some sort of Christian (1.6 million) were raised as Jews or are Jews by ancestry.[29] A 2015 study estimated some 450,000 American Muslims convert to Christianity, most of whom belong to an evangelical or Pentecostal community.[31]

National associations

The Federal Council of Churches, founded in 1908, marked the first major expression of a growing modern ecumenical movement among Christians in the United States. It was active in pressing for reform of public and private policies, particularly as they impacted the lives of those living in poverty, and developed a comprehensive and widely debated Social Creed which served as a humanitarian "bill of rights" for those seeking improvements in American life.

In 1950, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA (usually identified as National Council of Churches, or NCC) represented a dramatic expansion in the development of ecumenical cooperation. It was a merger of the Federal Council of Churches, the International Council of Religious Education, and several other interchurch ministries. Today, the NCC is a joint venture of 35 Christian denominations in the United States with 100,000 local congregations and 45,000,000 adherents. Its member communions include Mainline Protestant, Orthodox, African-American, Evangelical and historic Peace churches. The NCC took a prominent role in the Civil Rights Movement, and fostered the publication of the widely usedRevised Standard Version of the Bible, followed by an updated New Revised Standard Version, the first translation to benefit from the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The organization is headquartered in New York City, with a public policy office in Washington, DC. The NCC is related fraternally to hundreds of local and regional councils of churches, to other national councils across the globe, and to the World Council of Churches. All of these bodies are independently governed.

Carl McIntire led in organizing the American Council of Christian Churches (ACCC), now with 7 member bodies, in September 1941. It was a more militant and fundamentalist organization set up in opposition to what became the National Council of Churches. The organization is headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The ACCC is related fraternally to the International Council of Christian Churches. McIntire invited the Evangelicals for United Action to join with them, but those who met in St. Louis declined the offer.

First meeting in Chicago, Illinois in 1941, a committee was formed with Wright as chairman.A national conference for United Action Among Evangelicals was called to meet in April 1942. The National Association of Evangelicals was formed by a group of 147 people who met in St. Louis, Missouri on April 7–9, 1942. The organization was called the National Association of Evangelicals for United Action, soon shortened to the National Association of Evangelicals (NEA). There are currently 60 denominations with about 45,000 churches in the organization. The organization is headquartered in Washington, D.C. The NEA is related fraternally the World Evangelical Fellowship.

Neo-Orthodoxy

A less popular option was the neo-orthodox movement, which affirmed a higher view of Scripture than liberalism but did not tie the doctrines of the Christian faith to precise theories of Biblical inspiration. If anything, thinkers in this camp denounced such quibbling as a dangerous distraction from the duties of Christian discipleship. Neo-orthodoxy's highly contextual modes of reasoning often rendered its main premises incomprehensible to American thinkers and it was frequently dismissed as unrealistic.

Civil Rights Movement

As the center of community life, Black churches held a leadership role in the Civil Rights Movement. Their history as a focal point for the Black community and as a link between the Black and White worlds made them natural for this purpose.

Martin Luther King Jr. was but one of many notable Black ministers involved in the movement. He helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1957), serving as its first president. King received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end segregation and racial discrimination through non-violent civil disobedience. He was assassinated in 1968.

Ralph David Abernathy, Bernard Lee, Fred Shuttlesworth, C.T. Vivian and Jesse Jackson are among the many notable minister-activists.[32] They were especially important during the later years of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

See also

- Christianity in the United States

- Protestantism in the United States

- History of religion in the United States

- Religion in the United States

- List of Christian denominations

- History of Protestantism

- History of Roman Catholicism in the United States

- History of Christianity

- History of religion in the United States

- List of religious movements that began in the United States

References

- "Nones" on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have No Religious Affiliation, Pew Research Center (The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life), 9 October 2012

- "US Protestants no longer a majority - study". BBC News.

- "Mainline Churches: The Real Reason for Decline".

- James B. Bell, Empire, Religion and Revolution in Early Virginia, 1607-1786 (2013).

- Patricia U. Bonomi (2003). Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America. Oxford University Press. p. 16.

- Edward L. Bond and Joan R. Gundersen. The Episcopal Church in Virginia, 1607–2007 (2007)

- Jacob M. Blosser, "Irreverent Empire: Anglican Inattention in an Atlantic World," Church History, (2008) 77#3 pp. 596–628

- Edward L. Bond, "Anglican theology and devotion in James Blair's Virginia, 1685–1743," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, (1996) 104#3 pp. 313–40

- Richard R. Beeman, "Social Change and Cultural Conflict in Virginia: Lunenberg County, 1746 to 1774." William and Mary Quarterly (1978): 455-476. in JSTOR

- Rhys Isaac, The transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790 (1982)

- Francis J. Bremer, First Founders: American Puritans and Puritanism in an Atlantic World (2012)

- Emerson W. Baker. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience (2014).

- "Martin Luther". Totally History. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Ellis, John Tracy (1956). American Catholicism.

- Carnes, Mark C.; John A. Garraty; Patrick Williams (1996). Mapping America's Past: A Historical Atlas. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 50. ISBN 0-8050-4927-4.

- Kaminski, John (March 2002). "Religion and the Founding Fathers". Annotation - the Newsletter of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. 30:1. ISSN 0160-8460. Archived from the original on 2008-03-27.

- Matzko, John (2007). "The Encounter of the Young Joseph Smith with Presbyterianism". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 40 (3): 68–84. Presbyterian historian Matzko notes that "Oliver Cowdery claimed that Smith had been 'awakened' during a sermon by the Methodist minister George Lane."

- Dooley 11–15; McKivigan 27 (ritualism), 30, 51, 191, Osofsky; ANB Leonidas Polk

- Bilhartz, Terry D. (1986). Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-8386-3227-0.

- Jimmy Akin (2001-03-01). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- Bush, Jeb (March 4, 2009). NO:Choice forces educators to improve. The Atlanta Constitution-Journal.

- "Tennessee Anti-evolution Statute - UMKC School of Law". Archived from the original on 2009-05-20.

- Hakim, Joy (1995). War, Peace, and All That Jazz. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- Randall Balmer (2002). The Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. vii–viii.

- Patterson, Eric; Rybarczyk, Edmund (2007). The Future of Pentecostalism in the United States. New York: Lexington Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7391-2102-3.

- BBC -Religion & Ethics (2007-06-20). "Pentecostalism". Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. "Pentecostalism". Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- "How many Jews are there in the United States?". Pew Research Center.

- "A PORTRAIT OF JEWISH AMERICANS: Chapter 1: Population Estimates". Pew Research Center.

- "American-Jewish Population Rises to 6.8 Million". haaretz.

- Miller, Duane; Johnstone, Patrick (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10). Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "We Shall Overcome: The Players". Retrieved 2007-05-29.

Bibliography

- Abell, Aaron. The Urban Impact on American Protestantism, 1865-1900 (1943).

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People (1972, 2nd wed. 2004) the standard history excerpt and text search

- Allitt, Patrick. Religion in America Since 1945: A History (2004), very good overview

- Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists: Presenting Their History, Doctrine, Polity, Life, Leadership, Organization & Work Knoxville: Broadman Press, v 1–2 (1958), 1500 pp; 2 supplementary volumes 1958 and 1962; vol 5 = Index, 1984

- Bonomi, Patricia U. Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (1988) online edition

- Butler, Jon. Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. (1990). excerpt and text search

- Carpenter, Joel A. Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism (1999), good coverage of Fundamentalism since 1930

- Curtis, Susan. A Consuming Faith: The Social Gospel and Modern American Culture. (1991).

- Foster, Douglas Allen, and Anthony L. Dunnavant, eds. The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ (2004)

- Frey, Sylvia R. "The Visible Church: Historiography of African American Religion since Raboteau," Slavery and Abolition, Jan 2008, Vol. 29 Issue 1, pp 83–110

- Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity (1989). excerpt and text search

- Hein, David, and Gardiner H. Shattuck. The Episcopalians. (Praeger; 2004)

- Hempton, David. Methodism: Empire of the Spirit, (2005) ISBN 0-300-10614-9, major new interpretive history. Hempton concludes that Methodism was an international missionary movement of great spiritual power and organizational capacity; it energized people of all conditions and backgrounds; it was fueled by preachers who made severe sacrifices to bring souls to Christ; it grew with unprecedented speed, especially in America; it then sailed too complacently into the 20th century.

- Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Woman's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Harvard UP, 1993)

- Hill, Samuel, et al. Encyclopedia of Religion in the South (2005), comprehensive coverage

- Hutchison William R. Errand to the World: American Protestant Thought and Foreign Missions. (1987).

- Keller, Rosemary Skinner, Rosemary Radford Ruether, and Marie Cantlon, eds. Encyclopedia of Women And Religion in North America (3 vol 2006) excerpt and text search

- Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (2007), 412pp exxcerpt and text search

- Leonard, Bill J. Baptists in America. (2005), general survey and history by a Southern Baptist scholar

- Lippy, Charles H., ed. Encyclopedia of the American Religious Experience (3 vol. 1988)

- McClymond, Michael, ed. Encyclopedia of Religious Revivals in America. (2007. Vol. 1, A–Z: xxxii, 515 pp. Vol. 2, Primary Documents: xx, 663 pp. ISBN 0-313-32828-5/set.)

- McLoughlin, William G. Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America, 1607-1977 (1978). excerpt and text search

- Marty, Martin E. Modern American Religion, Vol. 1: The Irony of It All, 1893-1919 (1986); Modern American Religion. Vol. 2: The Noise of Conflict, 1919-1941 (1991); Modern American Religion, Volume 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941-1960 (1999), standard scholarly history

- Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925 (1980). very important history online edition

- Mathews, Donald. Religion in the Old South (1979)

- Melton, J. Gordon, ed. Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (2nd ed. 2009) 1386pp

- Miller, Randall M., Harry S. Stout, and Charles Reagan. Religion and the American Civil War (1998) excerpt and text search; complete edition online

- Queen, Edsward, ed. Encyclopedia of American Religious History (3rd ed. 3 vol 2009)

- Raboteau, Albert. Slave Religion: The "invisible Institution' in the Antebellum South, (1979)

- Richey, Russell E. et al. eds. United Methodism and American Culture. Vol. 1, Ecclesiology, Mission and Identity (1997); Vol. 2. The People(s) Called Methodist: Forms and Reforms of Their Life (1998); Vol. 3. Doctrines and Discipline (1999); Vol. 4, Questions for the Twenty-First Century Church. (1999), historical essays by scholars; focus on 20th century

- Schmidt, Jean Miller Grace Sufficient: A History of Women in American Methodism, 1760-1939, (1999)

- Schultz, Kevin M., and Paul Harvey. "Everywhere and Nowhere: Recent Trends in American Religious History and Historiography," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, March 2010, Vol. 78 Issue 1, pp 129–162

- Smith, Timothy L. Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War, 1957

- Sweet, W. W., ed. Religion on the American Frontier: vol I: Baptists, 1783-1830 (1931); Vol. II - The Presbyterians: 1783-1840 ; Volume III, The Congregationalists; Vol. IV, The Methodists (1931) online review about 800pp of documents in each

- Wigger, John H.. and Nathan O. Hatch, eds. Methodism and the Shaping of American Culture (2001) excerpt and text search, essays by scholars